As I’ve explained in previous articles on disqualification, I believe former President Donald J. Trump engaged in insurrection and is subject to disqualification from the presidency under Amendment XIV, Section Three.

However, even if I am correct, the process of invoking the Fourteenth Amendment against Mr. Trump is complex and disputed. Who is allowed to invoke it? The Supreme Court? Congress? A random election judge from Edina named Doris? What happens when she does?

After all, you can’t just walk into a room, invoke a law, and expect anything to happen. There’s a whole meme about this:

Successfully invoking a law requires four things: a law, an established fact pattern, a cause of action, and a remedy.1

I promise we’ll get back to Section Three in just a couple thousand words, but, first, I need to try to explain these four things in very general layman’s terms.2

A “rule of law” is a legal rule that says what is supposed to happen under a given set of circumstances. For example, “Whoever… is guilty of murder in the first degree… shall be sentenced to life imprisonment” (MN 609.185). Or the child tax credit: “There shall be allowed as a credit… with respect to each qualifying child… an amount equal to $1,000” (26 USC 24(a)3). Or: “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial” (U.S. Constitution, Amendment VI).

A “fact pattern” connects events in the real world to a rule of law. A fact pattern is what gets you from, “Murderers go to jail for life!” to “Rafael Edward Cruz, aka the Zodiac Killer, is going to jail for life!” It’s also how you get from “Each taxpayer gets a $1,000 credit for each qualifying child” to “I’m getting a $3,000 tax credit.” Very broadly, a fact pattern is just a set of circumstances, established in the eyes of the law by some process. That process may be the crucible of a criminal trial, with complex rules for gathering and presenting evidence. It may simply be you marking down on a tax form that you have three children, and the IRS takes your word for it. (Of course, if they audit you, you’d better be able to show them your children!)

So far, so easy, right? Now it gets a little more complicated.

A “cause of action” is a defined legal process that allows you to present your specific claim before some specific legal authority. For example, you can’t just grab the nearest IRS agent or police officer, shake him, and scream in his face, “You owe me three grand, bucko!” The legal process for claiming your tax credit, defined by IRS regulations, is “file Form 1040 by April 15 of the following year.” If there’s no available cause of action for your specific claim (and I am using that term very generally), then it doesn’t matter how theoretically correct you are; you are dead in the water.

For example, in Missouri law, if your ex harasses you by posting revenge porn online, you can go to the police and ask them to prosecute your ex under the Missouri Statutes, Section 573.110, Paragraph 6 (which defines revenge porn as a Class D Felony). The police can arrest your ex, and the district attorney can bring a criminal case against him (the cause for action). The penalty for a Class D Felony is a prison term of up to seven years and/or a fine of $10,000. However, suppose the police refuse to prosecute your ex. Maybe they don’t think they can prove it. Maybe the district attorney is swamped with murder cases and just can’t make time for revenge porn right now. Maybe they just don’t like you! Whatever the reason, you can’t force the government to prosecute under Paragraph 6, and only the government can bring a criminal prosecution cause of action like Paragraph 6. However, you can sue your ex under Paragraph 7, which establishes a “private cause of action” for revenge porn. Under this cause of action, you may recover up to $10,000 in damages from your ex, but you cannot get him thrown in prison.

Now, let’s move to Connecticut. If your ex posts revenge porn of you in Connecticut, you can, again, go to the police and ask them to prosecute your ex. This time, it will be under Connecticut Statutes, Section 53a-189c, Paragraph (c), which defines revenge porn as a Class D felony (1-5 years in prison and a fine of up to $5,000). However, unlike Missouri, Connecticut’s revenge porn law includes no private cause of action. Only the government can go after your ex for revenge porn. If the Connecticut government decides not to, because they don’t think they can prove it or they don’t like you or whatever, you’re out of luck. No Connecticut law allows you to take your ex to court for revenge porn.4 You have facts, and you have a rule of law that fits those facts, but you don’t have a legal cause for action.

The last thing you need is a “remedy.” When you use your cause of action to present your fact pattern and your rule of law to a legal authority, you have to ask that legal authority to actually do something about it. If you’re asking them to do something they can’t do, they won’t allow you to invoke the law at all. For example, if you go to a county court and ask them to free a prisoner from federal prison, they will very politely tell you, “No.” Even if you’re 100% correct that the rule of law demands the immediate release of the federal prisoner, the county court has no power to order it.

Here are some other things the county court can’t do, even if you ask it to, and even if the law is technically on your side: impeach the President; order Congress to pass a law; declare war against the Moon; or immediately dissolve the state of West Virginia. These remedies are not available to the court, so the court will turn you aside without even listening to your legal arguments.

Rule of Law: Sword or Shield?

A rule of law can be raised offensively or defensively. All my examples so far have been offensive examples. For example, if you sue your ex in Missouri for revenge porn, you will wield the rule of law against revenge porn against your ex in order to see him punished. This offensive posture is sometimes called “raising the law as a sword.”

However, a rule of law can also be raised defensively, “as a shield.” If someone brings a cause of action against you, you can automatically defend yourself by pointing to a rule of law that protects you. You do not need a cause for action to defend yourself. The person who brings the suit has to supply a cause; the defendant does not. For example, suppose your evil ex happens to be a foreign diplomat, protected by foreign immunity. You can still try to sue him under Missouri law, but your ex can respond to your lawsuit by raising “as a shield” the federal law on diplomatic immunity (22 USC 254d), which directs the Missouri courts to immediately dismiss your suit.

The same rule of law can be raised as either a “sword” or a “shield” in different contexts. For example, imagine that you are a Black slave in Missouri in December 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment is ratified, abolishing slavery.5 However, your (former) master rejects the amendment and refuses to give you your freedom. You now have two options.

First, you can simply walk away and dare your (former) master to come after you. If you are then arrested and brought before a judge under Missouri’s fugitive slave laws, you can point out that the Thirteenth Amendment abolishes slavery, and therefore the fugitive slave law does not apply to you (or anyone). The judge then has no choice but to dismiss the action your master has brought against you. You have raised the Thirteenth Amendment “as a shield.”

Second, you can file a suit petitioning for your freedom. You would sue your master under the Act of 30 December 1824, a Missouri law which creates a cause of action for people held in slavery to sue to prove they have a right to freedom. Having brought your suit, you would point the judge to the Thirteenth Amendment (an applicable rule of law) and demand your freedom (your remedy). You have raised the Thirteenth Amendment “as a sword.” Some states refused to create cause of action like this, leaving the unlawfully enslaved without this option.6 Missouri, happily, was not among them.

Law: Mandatory or Discretionary?

Many rules of law are mandatory. “Whoever… is guilty of murder in the first degree… shall be sentenced to life imprisonment” (MN 609.185) is pretty darn clear: if there’s a guilty verdict for Murder-1, then the sentencing official (in other words, the judge) must impose a life sentence.7 Not twenty-five years, not execution. Life imprisonment is the only option. Likewise, when the Constitution says, “No Bill of Attainder shall be passed,” that prohibition is mandatory. When the official responsible for executing (or abiding by) a legal mandate fails in this duty, he has performed a wrongful act.

Many other rules of law grant discretionary authority to specific persons. For example, under the Constitution, Congress “shall have the power… to provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting”. Congress has chosen to exercise this power (see 18 USC Chap. 25). However, it did not have to. The Constitution does not obligate Congress to criminalize counterfeiting; it simply gives Congress the power to do so, if Congress thinks it wise. The Constitution also gives Congress “the power… to grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal,” but Congress has not actually done so in over two hundred years.8 Congress has done nothing wrong by foregoing letters of marque. It has exercised discretion, as authorized by the Constitution.

Some rules of law do both. 13 USC 4 says, “The Secretary [of Commerce] shall perform the functions and duties imposed on him by this title, [and] may issue such rules and regulations as he deems necessary to carry out such[.]” The Commerce Secretary’s duties are mandatory, but her regulatory powers are discretionary. You can usually tell the difference between a mandatory duty and a discretionary power if you are fluent in normal English. However, there are many exceptions. Some are obvious, others less so.9

The bottom line is this: failure to perform a mandatory duty is a wrongful act. Refusal to carry out a discretionary power is a lawful choice.

Wrongful Acts Countered by Sword or Shield

An official who performs a wrongful act can be held accountable, but his accountability can only come from someone who has a legal cause of action to hold him accountable. Depending on the official, the particular wrongful act, and the shape of the law, his accountability might come from his boss, or from the governor, or from a Department of Internal Affairs. Very serious infractions might be criminal, leading to accountability by the police and district attorney. Judges are sometimes accountable only to the state legislature, which has the power to impeach. Occasionally, state law gives ordinary citizens a private cause of action, allowing citizens to sue officials who commit certain wrongful acts. Regardless, the person holding the wrongdoer accountable is raising the law “as a sword”.

Wrongful acts by a state official may also invalidate some of their actions. People who are targeted by those actions can then raise the law “as a shield” to protect themselves from those actions. For example, suppose the FBI catches you red-handed downloading Manhattan (1979) on your home computer and arrest you for criminal copyright infringement. After recovering in hospital for several weeks from acute embarrassment, you later discover that the warrant they used to enter your home was forged. When you go to court, you can raise the Fourth Amendment “as a shield,” because they did not have the right to enter your home to gather this evidence. This will almost certainly lead to your case being dismissed without penalty.10 However, this will not, by itself, get the police officer disciplined or fired, nor will you get any damages. All you get from pointing out a wrongful act “as a shield” is protection from official actions aimed at you.

What Is Section Three Doing?

The first sentence11 of Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment says:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.

This gives us a law: insurrectionists (who previously held office under oath)12 can’t hold office ever again. This law appears to be mandatory: as Justice Scalia says, “When the word shall can reasonably be read as mandatory, it ought to be so read.” The insurrectionist is given no discretion here (and the amendment would be incoherent if it did), and no one else is given any discretion, either. An insurrectionist who holds office anyway has therefore performed a wrongful act.

However, Section Three does not supply a cause of action. That is, Section Three does not give anyone a direct right to enforce its terms. Nor does it exclude anyone from enforcing its terms. Section Three is silent on its own enforcement.

Section Three does not supply a remedy, either. A remedy spells out exactly what a specific legal authority must do under certain circumstances. Section Three tells us that insurrectionists mustn’t hold office, but, without a cause of action, we don’t have the details we need to put that general prohibition into a concrete course of action.

Finally, Section Three does not supply a fact pattern. No law does. Only real-world events can supply facts, and only a legal process can alchemically transform facts into a fact pattern.

Now, in former President Trump’s case, the real world has supplied facts: the actions he performed on 6 January 2021 fell within the original public meaning of the words “engaging in insurrection” (as I have previously shown). Section Three provides a rule of law that matches these facts: insurrectionists can’t hold office.

However, as we explored above, having a rule of law and a nascent fact pattern on your side is only half the battle. Doris the election judge from Edina can’t walk into her voting precinct on Election Night 2024 and simply announce that her precinct is refusing to count votes cast for Donald J. Trump. She can’t even print out my blog posts and wave them around angrily at anyone who votes for Trump, much as I’d appreciate the promo. Under Minnesota law, election judges have no authority to judge candidate qualifications. Minnesota election judges are required to challenge voters, but, for candidates, they’re simply required to count all the votes cast.13 Section Three adds nothing to Judge Doris’s powers, because it provides no cause of action of its own.

Available Causes of Action on Day One

Section Three did not provide a cause of action on its own because it did not need to. From the get-go, various provisions of law already provided a cause of action for examining candidate qualifications. Once a cause of action was brought against an insurrectionist, Section Three provided the rule of law that cashiered him.

At the federal level, the big cause of action was the clause in Article I of the Constitution that states, “Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members.” If an unqualified person is elected to one of the houses of Congress, that house may, by simple majority vote, refuse to seat her. Since the Constitution makes each house the judge of elections, this power is exclusive; no court may override Congress’s final judgment, yea or nay. Once Section Three was official, Congress started launching disqualification votes (under Article I’s cause of action) against insurrectionists (under Section Three’s rule of law). Multiple people who had won free and fair elections in their home states went to Congress as members-elect… and Congress sent them home for failing to qualify.14

However, Article I’s “judge of qualifications” clause only reaches Congresspersons. How can the full sweep and force of Section Three be brought to bear against everyone else who is subject to it? Here we get into the delicious nitty-gritty of the law, where the grand abstractions of the Constitution are made real through endlessly detailed rules.

As of 9 July 1868, the date of the Fourteenth Amendment’s formal adoption, there were several other causes of action available. These arose largely under state law. I will focus on the laws of my home state of Minnesota, because I know it best, but I will make occasional excursions to other states where relevant.

First, and perhaps foremost, a plaintiff might seek a writ of quo warranto. The writ of quo warranto (“by what right?”) has been used for more than eight centuries to challenge the qualifications of office-holders. As an ancient writ descended from the England’s “common law,” the cause of action quo warranto was broadly recognized as being available even when not spelled out by statute, unless expressly extinguished. However, each state had slightly different rules about who could seek it and who could grant it. I don’t know how it worked in every state, so I’m going to tell you how it worked in (obviously) my home state of Minnesota. In Minnesota law in 1868, a quo warranto15 could be brought exclusively by the Attorney General, “on his own information, or upon the complaint of a private party,” whenever “any person usurps, intrudes to, or unlawfully holds or exercises any public office… within this state.” Only under rare circumstances could a citizen bring a quo warranto action without the consent of the Attorney General.16

Second, county canvassing boards, which granted certificates of election for certain offices such as sheriff, might object to a candidate’s qualifications. In Minnesota, this was not allowed.17 However, in Texas, the equivalent official (the chief justice of the county) did have the discretion to judge, at least, “whether the elections had been holden and the returns made… in comformity to the provisions of law.”18 North Carolina evidently had similar provisions, because, in 1869, the County Commissioners for Moore County refused point-blank to swear in Kenneth Worthy as sheriff, even though he won the most votes in an election, on the grounds that he was disqualified for insurrection under Section Three. Worthy sued, arguing that the County Commissioners had no right to intervene and that any challenge to his election should proceed under a quo warranto action. He lost, then lost again.

Third, the general public might be able to file an election challenge after the board certified the election. In Minnesota, anyone in the county could “contest the validity of an election, or the right of any person declared duly elected to his seat in the senate or house of representatives of this state” through a special election-challenge procedure (Chapter 1, Section 46, MN Statutes of 1866). This expressly gives Minnesota voters the right to challenge the qualifications of persons elected to the state legislature, though not to other offices. Other states, no doubt, had similar provisions.

Although the particular rules varied between states, the bottom line is clear: in general, states provided at least one cause of action whereby an ineligible candidate could be brought to court and his qualifications for office tried under the law. These causes of action, combined with the fact pattern of the Civil War and the law of Section Three, made it possible to disqualify insurrectionists immediately, without further federal legislation. Even the disqualified Mr. Worthy agreed that a cause of action was available to try his qualifications! He simply disagreed with the court about what cause was appropriate to his case.

It is no surprise, then, that, in the Readmission Act of 25 June 1868, Congress required six Southern states to bar insurrectionists from office as a condition for those states to be readmitted to the Union. This bill explicitly invoked Section Three, which would be officially adopted two weeks later. Tellingly, the Reconstruction Act did not create a cause of action explaining how insurrectionists should be disqualified. Congress presumed that they could do it themselves, since the tools for doing so had already been around for over six hundred years.

When an insurrectionist took office as a judge in Louisiana, an individual named Sandlin, with the blessing of the Attorney General, brought before the courts a civil action under Louisiana’s Intrusion Act (very similar to Minnesota’s civil quo warranto action). The Louisiana Supreme Court, citing the Readmission Act’s citation of Section Three for its rule of law, duly applied the rule of law, found the insurrectionist disqualified, and sent him home.19

It is also no surprise that, during the years just after Section Three became the law of the land, we saw hundreds and hundreds (and hundreds!) of ex-Confederates—including from states not covered by the Readmission Act—petitioning Congress for their disability under Section Three to be lifted.20

The major cause of action that we don’t see in 1868 is the pre-election ballot-access challenge, where action is taken to strike an ineligible candidate’s name from the ballot. This is because, in 1868, ballots as we know them did not exist. The Minnesota election code of 1866 has no provisions for organized ballot printing. Instead, it assumes that voters are either writing down the names of candidates themselves and dropping that piece of paper in the ballot box, or that local political parties are printing up ballots and handing them out to voters. In effect, all votes were write-in votes, and there was no way to know who would even be a voted-for candidate until after the ballots had been counted.

For completeness, I will mention three other causes of action that were already available under existing law on the day Section Three was adopted, without further enforcement legislation… even though none of these three causes was used.

In theory, incumbent federal officials, including judges, who were found to have been part of the rebellion could be removed under Section Three via impeachment proceedings under Article II of the Constitution. This was never tested, because the federal government was pretty much bare of insurrectionists by 1868.

In theory, an incumbent member of Congress who was found to have been part of the rebellion could be expelled under Article I. Whereas a member-elect who has not been seated may be found disqualified by a simple majority of his house through the “Judge of Qualifications” Clause, a member-elect who has been seated must be forcibly expelled under the Rules Clause, which requires a two-thirds majority of his house instead.

In theory, an insurrectionist could be prosecuted under the federal criminal law against insurrection. In addition to a prison sentence, conviction under this law automatically, by its text, deprives the convict of ever holding office again. This law was not an attempt to enforce Section Three, because it passed six years earlier, in 1862. It remains on the books today at 18 USC 2383. As far as anyone can tell, however, the criminal charge of insurrection has never once been enforced. Almost all Confederates received amnesty from criminal prosecution for insurrection in the Union’s terms of surrender, and this amnesty was eventually extended to every single Confederate. Obviously, immunity to criminal conviction did not immunize against Section 3 disqualification, so disqualifications continued without any criminal convictions.

In theory, if a disqualified person holding office tried to impose a fine or any other penalty on a citizen, that citizen would not need to bring a cause of action “as a sword”. He might then be able to raise Section Three “as a shield.” However, it would be very tricky, and I’ve found no record of it succeeding. More on this soon.

All of this came into force immediately the day Section Three was adopted. Not all of it could be used against every officer in every context, but much of it could and was.

This is crucial to bear in mind when somebody tells you that Section Three is totally inoperative without assistance from Section Five.

Oh, wait, I haven’t mentioned Section Five yet, have I?

What is Section Five Doing?

Section Five of the Fourteenth Amendment provides:

The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.21

Section Five is a law giving discretionary power to Congress to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment, including Section Three. If Congress chooses to exercise it, they can do lots of things with it to extend Section Three. They could define exactly what “engage in insurrection” means. In general, Congress’s definition will override other definitions offered by dictionaries, prior case law, and nineteenth-century conventions. The really obvious thing Congress could do here is supply a national cause of action for enforcement of Section Three, with a prescribed remedy. Congress can even restrict other causes of action, like state quo warranto actions.

However, Congress does not have to do any of this, because its Section Five power is discretionary. After all, Section Five was copied directly from the Thirteenth Amendment. The first part of the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery. The second part said, “Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” However, because slaves could already raise the first section of the Thirteenth Amendment both “as a sword” and “as a shield” against any masters stupid enough to continue resisting emancipation, there had been no perceived need for Congress to pass further enforcement legislation.22

It didn’t go the same way with Section Three. In May 1870, Congress did indeed exercise its enforcement power. The Ku Klux Klan Act laid out brand-new, crystal-clear, national causes of action for dealing with insurrectionists in office, including remedies:

§14. And be it further enacted, That whenever any person shall hold office, except as a member of Congress or of some State legislature, contrary to the provisions of [Section Three], it shall be the duty of the [U.S.] district attorney for the district… to proceed against such person, by writ of quo warranto, returnable to the circuit or district court of the United States in such district, and to prosecute the same to the removal of such person of office; and any writ of quo warranto so brought… shall take precedence of all other cases on the docket of the court…

§15. And be it further enacted, That any person who shall hereafter knowingly accept or hold any office… to which he is ineligible under [Section Three]… shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor against the United States, and, upon conviction thereof before the circuit or district court of the United States, shall be imprisoned not more than one year, or fined not exceeding one thousand dollars, or both, at the discretion of the court.

[…]

§8. And be it further enacted, That the district courts of the United States, within their respective districts, shall have, exclusively of the courts of the several States, cognizance of all crimes and offences committed against the provisions of this act, and also, concurrently with the circuit courts of the United States, of all causes, civil and criminal, arising under this act, except as herein otherwise provided… and all crimes and offences committed against the provisions of this act may be prosecuted by the indictment of a grand jury, or, in cases of crimes and offences not infamous, the prosecution may be either by indictment or information filed by the district attorney in a court having jurisdiction.

First, KKK Act §14 takes quo warranto national. Instead of leaving it in the hands of state attorneys general, this law lays a duty on U.S. district attorneys to use the writ against anyone who violates Section Three. (Notably, §14 makes clear that it isn’t doing the disqualifying. Section Three is doing the disqualifying. §14 is only providing a cause of action where Section Three can be applied.)

There is an exception in KKK Act §14 for people elected to Congress. This is, of course, because there was already a removal mechanism for people elected to Congress, and this removal mechanism was already being used. There is a second exception for state legislators. The reason for this exception is uncertain.23

Then, the KKK Act gives us a second cause of action in §15. While §14 simply removes people who violate Section Three from office, §15 calls on the criminal justice system to prosecute people who knowingly violate Section Three as criminals. (The “knowingly” is not in KKK Act Section 14.) §15 proceedings were full-blown criminal trials, with indictment, jury trial, a right against self-incrimination, the works… and the amnesty granted to ex-Confederates protected them only from criminal prosecution for past treason, not present usurpations. United States v. Powell has become the most well-known case brought under the §15 cause of action. (The defendant was acquitted.)

Finally, in §8, the KKK Act defines jurisdiction: any causes arising under §14 or §15 are charged exclusively to federal district and circuit courts. State courts are cut out of the loop entirely.

However, notice also what §8 does not cut out. Congress undoubtedly had the power, under Section Five, to suppress other state-level causes against unqualified officials.24 Instead, it left all the state-level causes we’ve discussed in place.25 That means that, as of June 1870, Minnesotans had the following causes of action available for dealing with insurrectionists who held, or attempted to hold, public office:

…or did they? According to some scholars today, a famous decision called Griffin’s Case26 proved some of my chart wrong. How much of my chart? That… actually isn’t clear. Let’s talk about Griffin’s Case.

In re Griffin

Throughout this section, I am deeply indebted to Tillman & Blackman’s analysis of Griffin’s Case in Sweeping and Forcing the President Into Section Three, Part II, pp. 404-496. Their lucid explanation illuminated the whole case for me, even in those few places where I reject their conclusions. I first read Griffin’s Case before reading Blackman & Tillman. Returning to it subsequently was like night and day.

In 1869, Caesar Griffin, a Virginian, was indicted and convicted for assault with intent to kill, sentenced to two years’ imprisonment, and handed over to the custody of the sheriff. Griffin, protesting, filed for a writ of habeas corpus in the federal district court for the District of Virginia. Griffin argued that the judge who had tried his case, one H.W. Sheffey, was not a judge at all, because Sheffey had been an insurrectionist. Therefore, Sheffey was disqualified from being a judge under Section Three. Therefore, all “Judge” Sheffey’s acts were null and void. Therefore, Griffin must be released, or, at the very least, be given a new trial. (This is called a “collateral attack” in legal jargon: Griffin isn’t defending himself in a case brought by the state, but counter-attacking by starting a new case against the state.)

There was a pretty big point in Mr. Griffin’s favor: Judge Sheffey was, without a doubt, an insurrectionist. If Section Three had been applied to Sheffey, he would have been disqualified. Alas for Mr. Griffin, nobody had (yet) applied Section Three to Sheffey.

After a lower-court judge ruled for Griffin, the case came on appeal to the Circuit Court for the District of Virginia, where it was decided by none other than Salmon P. Chase, then the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. (At the time, Supreme Court justices routinely had to sit solo, as mere appeals judges, in various courts around the country, for several months out of the year. This was called “riding circuit.”)

Because this was only a solo circuit court decision, not a decision of the Supreme Court, it is not binding precedent outside the now-extinct District of Virginia (now part of the Fourth Circuit). However, because it was a circuit court decision by a celebrated chief justice of the Supreme Court appointed by Lincoln himself, and because it is one of the only cases we have that touches on certain aspects of Section Three, people take it very seriously even though it is not strictly binding.

Chief Justice Chase considered the case and ruled against Griffin, who was returned to custody and (presumably) then served his sentence. No appeal was possible, because the only higher court was the Supreme Court, and Congress had passed a law in 1868 preventing the Supreme Court from hearing appeals in federal habeas corpus cases.

Chase based his decision on three main conclusions:

A writ of habeas corpus (raised here “as a sword”) allowed federal courts to examine and remedy certain alleged material and legal defects in a criminal trial, but only certain defects and certain remedies, directly relating to the federal rights of the prisoner. Chase ruled that a habeas action (under the limited federal habeas laws of 1869) could not examine a defect in the judge’s qualifications, so long as the (putative) judge did not violate the prisoner’s rights at trial and followed proper procedure. Since Mr. Griffin’s remedy was beyond the scope of a habeas corpus cause of action, Mr. Griffin could not bring this action in the first place. Case dismissed.

Even if the habeas collateral attack were allowed, and Mr. Griffin did force Judge Sheffey from office,27 it would not void Griffin’s prior conviction. Under the de facto officer doctrine, the acts of an officer acting under the color of an official title may remain valid even though it is later discovered that the office-holder’s title to office is legally defective. Chase ruled that the de facto officer doctrine applied here. Since Judge Sheffey’s trial of Mr. Griffin would remain valid even if Judge Sheffey were subsequently removed, Mr. Griffin could not seek Sheffey’s removal on a habeas cause. Case dismissed.

Even if Mr. Griffin could get around the de facto officer doctrine to attack Judge Sheffey’s qualifications, Chase could not apply Section Three to Judge Sheffey and nullify his acts without authorization from Congress. Section Three did not “instantly, on the day of its promulgation, vacate all offices held by [insurrectionists, nor] make all official acts, performed by them, since that day, null and void.” Chase’s court would need additional authority from Congress to remove Judge Sheffey and void all his official acts.

You can read his full ruling here.28

As the modern case over Donald Trump’s disqualification has developed, Griffin’s Case has come in for some intense criticism. Indeed, it was receiving new negative attention even in 2020. There is something to the criticism.

It seems to me that Chase should not have reached the question of Section Three’s applicability. The threshold question of whether Griffin could even examine Sheffey’s qualifications in a collateral attack via habeas corpus should have been answered first, and should have ended the case. The second threshold question of whether Sheffey is protected by the de facto officer doctrine should also have been answered before asking whether he had anything to be protected from. Chase, it seems to me, has engineered his decision to allow him to reach the merits of a question that he ought not have reached.29

That’s a little suspicious, in Chase’s case. Chase himself, though a former member of Lincoln’s own cabinet, had supported very favorable terms for the South, and publicly opposed Section Three when it was adopted. He considered Section Three too punitive to the South, and openly recognized that it “would exclude thousands from office,” complaining that this would “lead to complications which should be avoided.” When he reaches out, beyond the issues necessary to decide the case, in order to issue an opinion that clearly weakens Section Three, that has more than a whiff of politics about it—and Salmon P. Chase, a consummate politician, was still actively seeking the White House.

Even at the time, reaction to Chase’s decision was fierce, with Radical Republican publications saying things like:

We consider that decision of Chief Justice Chase not only entirely erroneous in point of law, but the most immoral in its character and the most atrocious in its consequences ever pronounced by an American judge. It is of far greater consequence, and if possible is more odious, than the opinion of Chief Justice Taney in the Dred Scott Case. If the decision of the Chief Justice is law, slavery may be re-established under the Constitution of the United States any day.

Whew! Even Michael Stokes Paulsen (one of our more pugilistic legal writers), only called Chase’s logic “warped” and accused him of “not shooting straight,” but the New York Sun in 1869 stopped just short of calling Chase literally Hitler—and only because Hitler wouldn’t be born for another twenty years! Even the moderate view taken by Blackman & Tillman suggests that Chase was writing this decision in part to communicate a message to Congress that would help Congress enforce Reconstruction.30 I just don’t think judges ought to be doing that sort of thing at all.

Too, Chase’s division between “literal” and “convenient” constructions so obviously fits into an atextualist framework for interpreting the law that a textualist can’t help flinching at it—even if, on a close examination, the atextualist rhetoric can be recast in textualist terms. I also think Chase’s presentation of the three separate issues—the scope of habeas relief, the de facto officer defense, and how Section Three might be applied in this posture—is not well-organized, thus unnecessarily difficult to follow, and far too easy to misunderstand or even misrepresent. His argument for the “punitive nature” of Section Three actually is based on unsalvageable atextualism, and his reasoning from there is tendentious. Perhaps the defect is mine, but I do find flaws in this decision.

On the other hand, much of Griffin’s Case is simply irrelevant to the matter of Trump’s disqualification, and, in my opinion, much of the rest of it can be reconciled with the view of Section Three I have already laid out.

Start with Chase’s first conclusion, on habeas corpus. Everyone agreed that Griffin (with the consent of the attorney general) could have brought a quo warranto action against Judge Sheffey. Griffin’s lawyer objected that it was ridiculous to assume that only a quo warranto could do the job. Sheffey’s lawyer said that the mere adoption of the amendment could not bypass the necessary process of quo warranto. Chase’s opinion said nothing at all about quo warranto or other existing causes of action, which were all a matter of state law and thus not part of this federal suit. The problem for Griffin is, Griffin wasn’t trying to question Sheffey’s qualifications in a quo warranto cause of action. Griffin was trying to do it in a habeas cause of action. (That’s for good reason: winning a quo warranto would have removed Sheffey, but would not have helped Griffin, who only cared about turfing out Sheffey if it helped Griffin get out of jail!)

I’m no expert in 1860s criminal procedure (and neither are you), but, as a layman, I found Sheffey’s lawyer’s argument compelling, and Chase simply agreed with him. Habeas (at least at the time) was not designed to be raised “as a sword,” but was limited to shielding oneself against immediate injustices, not examining the qualifications of those who meted justice out. Griffin had a fact pattern and a rule of law on his side, but he did not have a cause of action that could bring his rule of law to bear. On an 1869 habeas corpus, Griffin had no case.

Chase’s second conclusion, regarding the de facto officer doctrine, is also convincing. The de facto officer doctrine was well-established throughout the country at the time. For example, in Minnesota law (you know me!), in the case of Parker v. Dakota County Board of Supervisors, 4 Minn. 59 (1860), the Minnesota Supreme Court held that Seagrave Smith, who had incorrectly held office as Dakota County District Attorney from 1859-1860, had been correctly paid the D.A.’s salary during that time, since he was an officer de facto. Edward F. Parker,31 the rightful office-holder, was entitled to the office, and to future salary, but not to the salary that had already been paid out to Smith.

The Minnesota Supreme Court specifically held, “The acts of an officer de facto who comes into office by color of title are valid so far as the public and third persons are concerned until he is ousted by quo warranto. This principle has been settled by an uninterrupted series of judicial decisions, and does not require the citation of authorities to prove it.” Minnesota’s conclusion comports perfectly with Chase’s.

It ought to. I know we all skipped to the bottom of the Griffin PDF to read Chase’s controlling opinion, but, if you take the time to read Bradley T. Johnson’s32 defense of Judge Sheffey, Johnson cites overwhelming precedent to precisely the same effect: the acts of an officer de facto cannot be attacked collaterally, but the officer himself may be attacked in a proceeding in the nature of a quo warranto. He even digs up a case in Wisconsin where a convict was imprisoned by a judge who was later found to be illegally in office (due to confusion over residency requirements33), the convict sought release via a habeas corpus, and the Wisconsin Supreme Court denied the writ because “where a party was… tried, convicted, and sentenced… by a person who exercised the office of judge… without authority of law, the sentence [is] nevertheless binding.” (State v. Bloom, 17 Wis. 521 (1863)). Chase’s ruling on this question, even if not taken as proved, is clearly within the mainstream of 1869 American law on this point.

Chase’s third conclusion is the only one that rustles the jimmies of those of us on Team Disqualification, since it rules there are limits on Section Three’s (judicially cognizable) effects. But let’s look closely at what Chase says:

…persons in office by lawful appointment or election before the promulgation of the fourteenth amendment, are not removed there from by the direct and immediate effect of the prohibition to hold office contained in the third section…

[I]t is obviously impossible to [remove an officer] by a simple declaration, whether in the constitution or in an act of congress, that all persons included within a particular description shall not hold office. For, in the very nature of things, it must be ascertained what particular individuals are embraced by the definition, before any sentence of exclusion can be made to operate. To accomplish this ascertainment and ensure effective results, proceedings, evidence, decisions, and enforcements of decisions, more or less formal, are indispensable…

But we agree with this! We don’t think that office-holders excluded by the Fourteenth Amendment are removed by its “direct and immediate effect.”34 Instead, as I’ve shown you, we believe that, when someone is disqualified by real-world facts, a cause of action must be brought to a competent legal authority which can, in orderly proceedings, take evidence, establish a fact pattern, apply the proper rule of law, and order the appropriate remedy. (The official actions of such an office-holder, even if found to be disqualified, may well be shielded under the de facto officer doctrine.) This framework is why Doris the election judge from Edina can’t storm into a polling place and shout, Michael-Scott-style, “I declare DISQUALIFICATION!”

For an incumbent state officer, disqualification and removal could likely only be accomplished in a quo warranto action. For an incumbent state or federal legislator, by expulsion. For any other incumbent federal officer, impeachment. For a federal judge to remove officers by any other means did indeed require action from Congress under Section Five. And Griffin tried to pull it off as a collateral attack in a habeas cause of action. Of course it didn’t work. It shouldn’t have.

The only apparent disagreement between the Trump Disqualification plaintiffs and Chase is something Chase says several times:

To accomplish this ascertainment and ensure effective results, proceedings, evidence, decisions, and enforcements of decisions, more or less formal, are indispensable; and these can only be provided for by congress.

…persons in office by lawful appointment or election before the promulgation of the fourteenth amendment, are not removed there from by the direct and immediate effect…; legislation by congress is necessary to give effect to the prohibition, by providing for such removal.

Chase seems to be saying that the cause of action removing someone from office can “only be provided for by Congress,” to the exclusion of the states. He expounds on this at some length:

Now, the necessity of this is recognized by the amendment itself, in its fifth and final section, which declares that “congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provision of this article.”

There are, indeed, other sections than the third, to the enforcement of which legislation is necessary; but there is no one which more clearly requires legislation in order to give effect to it. The fifth section qualifies the third to the same extent as it would if the whole amendment consisted of these two sections. And the final clause of the third section itself is significant. It gives to congress absolute control of the whole operation of the amendment. These are its words: “But congress may, by a vote of two-thirds of each house, remove such disability.” Taking the third section then, in its completeness with this final clause, it seems to put beyond reasonable question the conclusion that the intention of the people of the United States, in adopting the fourteenth amendment, was to create a disability, to be removed in proper cases by a two-thirds vote, and to be made operative in other cases by the legislation of congress in its ordinary course. This construction gives certain effect to the undoubted intent of the amendment to insure the exclusion from office of the designated class of persons, if not relieved from their disabilities, and avoids the manifold evils which must attend the construction insisted upon by the counsel for the petitioner.

This is a curious claim. If we interpret Chase literally, as Team Trump would like us to do, then Section Three was totally ineffectual until “brought to life” by Section Five legislation passed by both houses of Congress and presented to the President. If we interpret Chase literally here, then the enforceability of Section Three at the time of Griffin’s Case looked like this:

![Table reading as follows: In 1869 Minnesota, This Cause of Action… "…Could Be Used Against These Officials for Violating Section Three (according to an overly literal interpretation of Justice Chase's opinion in Griffin's Case)" Elected but not Sworn-In Sworn-In "§46 Election Challenge by any voter" [barred by Section Five] [not usable] "§49 Election Challenge by any voter" [barred by Section Five] [not usable] "Quo Warranto by Minn. attorney general (or by his consent)" [not usable] [barred by Section Five] "State Legislative Expulsion by relevant house of Minn. Legislature (two-thirds majority)" [not usable] [barred by Section Five] "Denial of Election Certificate by election canvassing board" [barred in ALL states by Section Five] [not usable] "Article I Disqualification by relevant house of Congress (simple majority)" [barred by Section Five] [not usable] "Article I Expulsion by relevant house of Congress (two-thirds majority)" [not usable] [barred by Section Five] "KKK Act §14 Quo Warranto by U.S. district attorney" [not passed until 1870] [not passed until 1870] "Article II Impeachment by Congress" [barred by Section Five] [barred by Section Five] "18 USC 2383 prosecution by federal law enforcement" [not passed under Section Five, therefore barred by Section Five] [not passed under Section Five, therefore barred by Section Five] "KKK Act §15 Misdemeanor by federal law enforcement" [not passed until 1870] [not passed until 1870] "Invalidation ""as a shield"" by anyone government official targets" [not usable] [barred by Section Five] "Pre-Election Removal from Ballot by Secretary of State or Minn. Supreme Court" [not usable; modern ballots not yet invented] [not usable; modern ballots not yet invented] Also, according to this interpretation, Section One of Amendment XIII is also inoperative "as a sword" without Congressional legislation and therefore chattel slavery is technically still not entirely illegal. Whoops! Table reading as follows: In 1869 Minnesota, This Cause of Action… "…Could Be Used Against These Officials for Violating Section Three (according to an overly literal interpretation of Justice Chase's opinion in Griffin's Case)" Elected but not Sworn-In Sworn-In "§46 Election Challenge by any voter" [barred by Section Five] [not usable] "§49 Election Challenge by any voter" [barred by Section Five] [not usable] "Quo Warranto by Minn. attorney general (or by his consent)" [not usable] [barred by Section Five] "State Legislative Expulsion by relevant house of Minn. Legislature (two-thirds majority)" [not usable] [barred by Section Five] "Denial of Election Certificate by election canvassing board" [barred in ALL states by Section Five] [not usable] "Article I Disqualification by relevant house of Congress (simple majority)" [barred by Section Five] [not usable] "Article I Expulsion by relevant house of Congress (two-thirds majority)" [not usable] [barred by Section Five] "KKK Act §14 Quo Warranto by U.S. district attorney" [not passed until 1870] [not passed until 1870] "Article II Impeachment by Congress" [barred by Section Five] [barred by Section Five] "18 USC 2383 prosecution by federal law enforcement" [not passed under Section Five, therefore barred by Section Five] [not passed under Section Five, therefore barred by Section Five] "KKK Act §15 Misdemeanor by federal law enforcement" [not passed until 1870] [not passed until 1870] "Invalidation ""as a shield"" by anyone government official targets" [not usable] [barred by Section Five] "Pre-Election Removal from Ballot by Secretary of State or Minn. Supreme Court" [not usable; modern ballots not yet invented] [not usable; modern ballots not yet invented] Also, according to this interpretation, Section One of Amendment XIII is also inoperative "as a sword" without Congressional legislation and therefore chattel slavery is technically still not entirely illegal. Whoops!](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdf375ec7-785e-4f4d-8e79-b2aebf029251_804x899.png)

But Chase himself cautions against reading things too literally, and for good reason.35

This literal construction proves too much. If we take Chase absolutely at his word, the Section Three cannot be invoked in already-existing state-based quo warranto procedures. Chase says nothing of the sort. Both parties in the case agree, without the slightest question, that, obviously, state-based quo warranto actions could be taken against disqualified judges. Though often neglected today, these remedies were (as we see in this and other cases) well known to the 1869 American legal community. If Chase had intended to stamp out Section Three’s application even in appropriate causes of action, Chase would have said so explicitly—and indeed he would have needed to say so explicitly. No judicial decision should be taken to restrict a highly salient application of the law across an entire category of existing common-law and state-law causes by mere implication. Chase doesn’t even directly mention these causes.

There are other problems. If we take literally Chase’s claim that Section Three must be “made operative in other cases by the legislation of congress in its ordinary course,” then individual houses of Congress could not exercise authority under Article I to expel or exclude insurrectionists acting alone (as Article I prescribes). Instead, before Congress could exclude any insurrectionist using Section Three + Article I, Congress would have to establish that procedure through legislation passed by both houses and presented to the President. In other words, taken too literally, Chase’s interpretation would partially repeal the “Judge of Qualifications” clause! (It would have similar effects on Article II impeachment power.)

In reality, Congress liberally and repeatedly exercised the power to exclude insurrectionists, both before and after Griffin’s Case. No special legislation ever authorized it, and Chase does not complain about nor condemn it in his decision. We see from this that Chase does not mean that every use of Section Three must flow from legislation passed under Section Five. (Or, in the unlikely event that he did, no one paid any attention.)

It gets worse from there. The Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, is also enhanced (or, in the literalist view, saddled) by a passage very similar to Section Five. Chase wrote in Griffin’s Case that, “The fifth section qualifies the third to the same extent as it would if the whole amendment consisted of these two sections.” Well, in the Thirteenth Amendment, the whole amendment did consist of just the two sections. After the first section abolished slavery, the second section gave Congress the power to pass “appropriate legislation” to enforce the Thirteenth Amendment. Yet Congress had never expressly passed legislation abolishing chattel slavery.36 If we interpret Chase literally, and apply that literalism to the Thirteenth Amendment (as his language makes clear we must), then what follows? Was the Thirteenth Amendment impossible to raise “as a sword,” then, in a cause of action such as a freedom suit? Did slaves need to contrive to be accused of something before they could raise the Thirteenth Amendment “as a shield” and secure legal recognition of their freedom? I am woefully ignorant of many things, but I, at least, am not aware of any evidence for this alarming conclusion. The Thirteenth Amendment seems to have worked just fine, even without enforcement legislation.

Let us interpret Chase according to his own words on interpretation: “a construction, which must necessarily occasion great public and private mischief, must never be preferred to a construction which will occasion neither, or neither in so great degree, unless the terms of the instrument absolutely require such preference.” If we literally interpret Chase’s admittedly strong language about Congress’s “absolute control” over Section Three and the “necessity” of “only Congress” passing legislation to bring Section Three into affect, it would indeed occasion all these public and private mischiefs, and perhaps more.

So we may rest assured that Justice Chase was not literally saying that all Section Three disqualifications must emanate exclusively from Section Five. What, then, was Justice Chase saying?

I think it’s important here to remember the context of the case.

Chase was a federal judge considering a federal writ of habeas corpus that sought to vacate proceedings in a state court by disqualifying a state judge. Return to our original chart from a few pages ago:

Remember that the KKK Act had not yet been passed at the time of Griffin’s Case, so those causes aren’t available. Remember, also, that, by 1869, every single Confederate had received a criminal pardon, so prosecution under 18 USC 2383 was also unavailable. Setting aside those unavailable causes, do you see any cause of action on there that would allow a federal official to remove a state officer? Or, indeed, a cause that would allow a federal judge to remove any officer at all?

You do not, because there isn’t one. Mr. Griffin tried to invent one in this case out of the federal habeas clause and a misconception of how Section Three could be raised “as a shield,” but Chase correctly shut it down. So Chase’s ruling is best read as holding that, as of 1869, the federal courts had no cause of action to remove a disqualified official from power, and that only Congress could supply such a cause. This ruling was correct.

There are additional details that Chase mentions which support his theory that Congress had not authorized him to remove Sheffey from office. These details were important to Chase’s argument at the time, but no longer apply today, and therefore serve to distinguish Griffin’s Case from modern disqualification cases.

First, Chase noted that Congress had implicitly blessed Sheffey’s tenure in office when it recognized Virginia’s reconstruction government (which had installed Sheffey). This had all happened prior to the adoption of Section Three.

Second, Chase noted that Congress had, in fact, already provided a federal cause of action for Sheffey’s removal, and that this cause bypassed the federal judiciary altogether. A few months before Chase decided Griffin’s Case, Congress had passed a law mandating that Reconstruction military commanders must remove disqualified officers. (This cause of action is not on my Minnesota chart, because it came from special legislation which Congress applied only to Virginia, Texas, and Mississippi.) This cause of action did in fact lead to Judge Sheffey’s removal from office less than six months after Griffin’s Case was decided. The fact that this cause existed, but bypassed the courts, provided evidence that Congress did not want federal courts spontaneously enlarging their own jurisdictions without guidance from Congress.

So the best reading of Chase’s third holding in Griffin’s Case is simply this: a federal judge cannot disqualify an officer without a clear federal cause of action putting the question into a federal courtroom. There was no such cause of action at the time. It is undisputed that federal causes of action can only come from federal law, and only Congress can write federal law. Therefore, Chase held, he and other federal judges could not enforce Section Three without further enabling legislation from Congress.

None of this impugns state-based enforcement of Section Three to the slightest degree, and Chase’s silence about the availability of state quo warranto actions (especially after both opposing and defending counsel acknowledged their ability to handle Section Three cases) is best read as confirmation that he had no intention of suppressing Section Three in state-law actions on qualifications.

Congress appears to have responded to Chase’s valid concern about the lack of federal causes of action by passing the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1870, discussed above. As we saw, the KKK Act did precisely what Chase had suggested here in Griffin’s Case: it created two new federal causes of action for pursuing disqualified office-holders, while leaving all existing causes of action untouched.

Chase’s decision, then, though correct, simply has absolutely nothing to do with state causes of action dealing with strictly state officials and state actions.37 To read it that way brings Chase’s ruling into conflict with too many other laws and precedents—a woodenly literal approach that Chase himself warns against.38

Read in this light, Chase’s opinion stands in perfect harmony with the complicated state-and-federal framework for adjudicating qualifications. We may quibble about portions of his language and his logic, but there ceases to be any need to see Chase or Griffin’s Case as standing in dramatic opposition to cases like Worthy v. Barrett.

More to the point: read in this light, Chase’s opinion is perfectly in line with the recent attempts, in Minnesota and Colorado, to remove Donald Trump from state-printed ballots on grounds of his Section Three disqualification.

See? I did promise we’d get back to Trump eventually.

A State Remedy for a State Cause

Today, federal causes of action for enforcing Section Three are severely limited. Congress retains its constitutional authority to exclude or expel legislators, and to impeach officers. That’s… about it.

The Ku Klux Klan Act was repealed decades ago, so its §14 federal quo warranto action is extinguished. There is no federal common law, so there is no federal common-law writ of quo warranto, and, then as now, a federal court cannot just spontaneously issue one. Disqualification “as a shield,” then as now, is problematic, because the de facto officer doctrine remains strong. It’s therefore very hard to block a disqualified-but-elected federal legislator from taking office, and even harder to eject a disqualified federal legislator or officer already sworn in.

However, in the modern era, states print ballots. Candidates who wish to appear on state ballots must petition states to place them upon the ballot. Each state has different requirements for this. In some states, prior to being placed on the ballot, there is a window during which a voter or rival has a cause of action to challenge the candidate’s qualifications to hold office.

In 2023 Minnesota, the old Civil War-era election challenge statutes have long since been replaced by just such a cause of action: Minn. Rev. Stat. §204B.44, which I’ve written about extensively. In Minnesota, Trump’s challengers timely brought their action under this challenge statute. To the best of my (limited) understanding of Colorado law, Colorado’s election challenge framework is similar, and Trump’s challengers in that state brought their action the same way.

In other words, armed with a fact pattern (Trump’s insurrection) and Section Three’s rule of law (insurrectionists are disqualified), petitioners brought a cause of action under a duly-enacted state law (the ballot challenge law), seeking a state remedy that was well within the reach of the state court in which the cause was brought. After all, petitioners didn’t ask Minnesota or Colorado courts to imprison Trump, or disqualify him in every state, or impeach incumbent insurrectionist federal officers. Petitioners asked the state courts to instruct their respective secretaries of state to correct a state ballot in a state-run election established (ultimately) under the state’s plenary Article II authority to choose the state’s own electors.

They have the quadfecta: a rule of law, a fact pattern that fits it, a cause of action, and an appropriate remedy. Chief Justice Chase himself could not but smile upon this eminently sensible and entirely traditional approach to the age-old problem of enforcing constitutional qualifications for office.

“Self-Executing” is a Bad Word

We are done. Finally. This is the end of not only this gigantic article, but of my series of gigantic articles covering all four of the central topics in the Disqualification Suits: the democratic legitimacy of disqualification, the insurrection itself, the “officers of the United States” language in Section Three, and, finally, this article about Griffin’s Case and whether Section Three is self-executing.

“Wait,” you say. “Self-executing? What’s that?”

Even though this article is about whether Section Three is “self-executing”, I never actually used the term, “self-executing”. That is because I find this term dangerously ambiguous.

Some people seem to believe that, if a legal text is self-executing, it supplies not only a rule of law, but also a universal cause of action and a universal remedy of indefinite shape and scope. For example, some people believe that, if Section Three is “self-executing,” that means Doris the Edina Election Judge actually can just burst into a room, declare Donald Trump disqualified, and tear up any ballots cast for him!

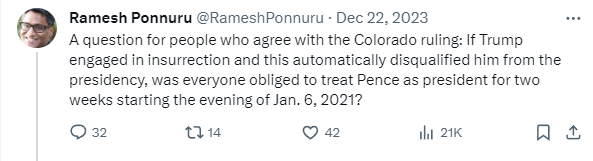

This isn’t just rubes, either. As far as I can tell, this is what Ramesh Ponnuru thinks Disqualifiers mean by “self-executing”:

Ramesh is brilliant, one of the best. If he thinks that’s what self-execution means, we’ve failed to communicate a consistent (or sane) meaning of “self-execution.” If Ponnuru can make this mistake, it’s very easy to imagine Justice Alito or one of the other conservatives making the same error and ruling against the disqualification case on a knee-jerk misunderstanding.

The problem is, if you ask three lawyers what “self-execution” means, you are likely to get four answers about what, precisely, a self-executing law supplies. In my view, Section Three supplies a rule of law, not a cause of action or a remedy, but the rule of law is mandatory and effective upon adoption. Is that “self-executing?” Depends who you ask. (Because I avoided using the word “self-executing” in this already-immense article, I didn’t have to guide you through the fens of self-executing treaty law, which is a nightmare and everyone admits it.)

I see no reason to get drawn into this semantic quicksand, and I advise you, like me, to simply avoid the term “self-executing” whenever you possibly can. Talk about what Section Three supplies or does not supply—a rule of law, a cause of action, a remedy, jurisdiction, whatever—but name it specifically, in clear language, rather than trying to let a controversial and unstable term do the work for you. Team Trump will accuse you of exaggerating Section Three no matter what, but don’t make their job easier by handing them ambiguous pull quotes they can recast as a parade of horribles.

Supreme Court Outlook

At the end of my “Officers of the United States” article, I said that I think the “officers” debate is a complicated and surprisingly close question, where people of good conscience, reasonable intelligence, and a clear understanding of the issues might look at exactly the same pile of data and draw different conclusions. Much of the “officers” debate comes down to a tug-of-war between the Ordinary-Meaning Canon (#6 in Scalia’s book) and the Consistent-Usage Canon (#22 in the same book). When both canons cannot be perfectly followed, it’s difficult to resolve exactly how much weight should be given to each.

I don’t think that’s the case in the “self-execution” debate. There is a clearly correct answer here: if state law creates an appropriate cause of action, state courts do not require any enabling legislation from Congress to apply Section Three. Section Five poses no obstacle to the Trump Disqualification Suits.39

However, if the Supreme Court were to rule otherwise—if they held that Colorado really can’t enforce Section Three without further authorization from Congress—I can’t help noticing that it would provide a very convenient political escape for the justices. It would kick the issue of Trump’s disqualification straight from the Supreme Court to Congress, leaving a minimal footprint on the 2024 election and minimal damage to other areas of the law. The ruling would effectively nullify Section Three, but it would get the Court out of a political jam.

That makes me think that Chief Justice John Roberts is probably working the chambers right this moment, trying to convince the other justices to sign on to this (wrong) theory of how Section Three and Section Five interact. John Roberts’ highest goal is to get out of political jams, and he isn’t especially interested these days in what the law actually requires. Whether he can get five votes for this position, however, remains to be seen.

I guess that’s a bit of a preview for you: if the Supreme Court rules against Colorado on these grounds, I am going to suspect that we lost because of politics, not because of legal arguments. I hope that doesn’t happen. On the other hand, if the Court rules against Colorado because they decide the President is not “an officer of the United States,” I would disagree, but I would be inclined to accept it as an honest textual disagreement. Of course, I am still hoping that the real outcome here is that the Supreme Court agrees with me, and takes Donald J. Trump off the ballot this fall.

Programming notes: From here on out, I expect I will just be filing routine updates on briefs, filings, and of course oral arguments and (ultimately) the Supreme Court’s final decision. I also plan to publish a Worthy Reads later this month (finally!).

Also, a bunch of other things, from jurisdiction to standing to court fees… but I am trying to write a blog post, not put you through law school. As relevant to today’s topic, the four things you need are a cause of action, a remedy, a law, and an established fact pattern.

Please do not try to use these definitions in a courtroom; they are rather too general. If you refer to a Form 1040 as a “cause of action,” you will, at best, get some real weird looks. Each of the four terms I introduce here are the subjects of multiple very large books.

Nonetheless, since these four elements are what carry any law from a statute book into the real world, it’s vital to see them and how they hook together.

The amount is technically $2,000 at the moment, thanks to a sneaky insertion the Trump tax cuts made in subsection (h), but—alas for my tax bill—it’s temporary. The Trump tax cuts expire in tax year 2025 (so they’ll disappear from your tax forms in April 2026).

You may still be able to punish your ex for the revenge porn by creatively interpreting some other Connecticut or federal law to fit the fact pattern. For example, his revenge porn may well constitute harassment in the second degree (CT Statutes 53a-183). A large part of a lawyer’s job is knowing the statute book well enough that he can take any evil fact pattern and match it to some law somewhere.

My personal favorite is going after revenge-porn producers for copyright infringement, which is not only a federal cause of action available to everyone (17 USC 501(b)), but can sock your evil ex with absurdly large fines. U.S. copyright law is completely bonkers and fairly evil, but you can’t change that, so why not use it against your ex? Statutory damages for infringement start at $750, but can scale up to $150,000 per infringement, with each individual nude photo or video constituting a separate infringement.

However, at this point, legally speaking, you’re no longer going after your ex for revenge porn. You’re going after your ex for harassment or copyright infringement, because the law doesn’t allow you to go after him for revenge porn.

One final note: In 2022-23, Massachusetts tried, but failed, to pass a revenge porn law. As a result, there is no law against revenge porn in Massachusetts. If your ex does revenge porn against you in Massachusetts, you can’t take him to court for it. However, the problem in this case is not simply that you lack a cause of action. The problem in this case is that you lack a law altogether! Sure, the law of human nature cries out for justice against your ex, as suggested in my review of Dredd, but natural law is, with rare exceptions, not enforceable in United States courts.

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1862 freed all the millions of slaves in rebel territory, but it didn’t affect slavery in loyal states. Today, we celebrate Juneteenth, the day in June 1865 when the Emancipation Proclamation was finally implemented throughout the entire South… but tens of thousands of people were still legally held in bondage until December 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery everywhere in the United States.

To be sure, Missouri had already abolished slavery (by state law) on 11 January 1865, eleven months and one week before the Thirteenth Amendment was adopted. However, your (putative) master kept this information from you, so you remained in bondage. News of the Thirteenth Amendment’s adoption, however, was impossible to contain.

This is perhaps not as implausible as it sounds. West Virginia abolished slavery on 3 February 1865. (“And the smoke of its torment ascendeth up forever and ever!”) However, at least according to Wikipedia’s account of an undergraduate honors thesis I have been unable to access, even local newspapers continued printing fugitive slave ads for weeks or months afterwards. The slippery space between proclamation of a law and implementation of that law is fascinating stuff, usually overlooked in history class.

In some cases, a slave with a right to freedom could sue on other grounds, such as false imprisonment.

Edward M. Post wrote a very interesting 1985 paper, entitled “Kentucky Law Concerning Emancipation or Freedom of Slaves” (The Filson Club History Quarterly, Vol 59 No 3) describing the history of “freedom suits” in nearby Kentucky. Kentucky seems to have had no actual freedom suit statute, but did have several causes of action slaves could use to appeal for freedom: false imprisonment actions, suits to enforce contracts or the acts of other states, and possibly options available through the unwritten “common law” of old England. Actual slaves had no right to sue, but, if a slave claimed to be free, the slave was presumed free, for the purposes of sustaining the lawsuit, until the case could be decided.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to track down many of the statutory or judicial authorities Mr. Post used in his article, so I can’t say much more about this beyond, “Say, that’s neat!” Missouri law is much more clear-cut, so that’s the example I’m using.

We are considering this statute in isolation. In a real-world case, other laws could interact with this one, creating exceptions and loopholes. However, in and of itself, MN 609.185 is mandatory and inflexible.

Although Congress has not issued letters of marque since the War of 1812, the pretended Confederate government attempted to issue letters of marque during the Civil War. This gave rise to the case U.S. v. Greathouse (1863), which I discussed in my recent article, “The President’s Insurrection.”

Justice Scalia’s book with Bryan Garner, Reading Law, spends three pages going over the many ways “shall” can be used, abused, and simply misunderstood, concluding: “Shall, in short, is a semantic mess.” Scalia & Garner mention a 2010 law review article by none other than Seth Barrett Tillman (a by-now familiar character) and his wife, entitled “A Fragment on Shall and May,” which very briefly describes certain differences between “shall” in modern American English, colonial-era Scots-English, and colonial-era Anglo-English.

Nonetheless, despite the many vagaries of “shall,” Scalia & Garner circle back to the conventional wisdom: “All this having been said, when the word shall can be reasonably construed as mandatory, it ought to be so read.” (Reading Law, Canon 11)

The “exclusionary rule,” where evidence gathered illegally cannot be admitted in a court of law, is surprisingly complicated and surpassingly technical. I have evaded many technicalities in this simple example.

The second sentence of Section Three reads:

But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

This is pretty plainly a discretionary power charged to Congress. The pattern here is strong: Section Three’s disability is mandatory, but Congress may relieve it at Congress’s discretion.

For brevity, I will not add the qualification “who previously held office under oath” every time I refer in this article to insurrectionists disqualified by Section Three. I trust you to remember that Section Three applies, not to every insurrectionist, but only to oath-breaking insurrectionists of this sort.

Certain write-in votes are excluded by county canvassing boards later on, but those boards aren’t permitted to evaluate candidate qualifications, either.

The House and Senate formally considered the qualifications of Roderick Butler, Francis Shober, Philip Thomas, John Christy, John Rice, George Booker, Joseph Abbot, and Lewis McKenzie in light of Section Three. Some details of each case are given in Hind’s Precedents of the House, Volume I, sections 454 (p462) to 463 (p486). Myles Lynch also explores these and other cases in “Disloyalty & Disqualification,” written (importantly) before the J6 insurrection.

Hind’s Precedents also lists (sections 448-453) several cases where candidates were investigated and disqualified under the 1862 Ironclad Oath, a close forerunner of Section Three, which was used against members-elect several times after Section Three had been passed by Congress but before it had been ratified by the states. However, I have not included those cases here.

Thomas, Abbot, and Christy were ruled unqualified and sent home.

Booker, McKenzie, and Rice were investigated, found innocent of disloyalty, and allowed to stay. All three had been allowed to take the Oath while the investigation was pending, leading to an awkward situation had the investigations found them disloyal: having already been admitted, it would seem that they could only be expelled by a two-thirds vote, not simply denied admission by simple majority, since Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution states, “Each House may… with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member.” Fortunately, that didn’t happen.

Butler and Shober were ruled disqualified, but eventually admitted after great delay on condition that they swear solemn oaths of everlasting loyalty. To facilitate their admission, Congress had to pass a bill, by two-thirds majorities, formally lifting their disqualification.

Thomas’s exclusion was hinky, because the Fourteenth Amendment had been proposed but not yet ratified by enough states. There was debate within the Senate about whether Section Three was legally in operation or not. Their debate was inconclusive. In reality, it was not yet in operation. Thomas might still have been excluded under the 1862 Ironclad Oath, but the validity of requiring elected officials to swear the Ironclad Oath before Section Three’s ratification was often questioned.

Some technical notes.

Strictly speaking, basically any quo warranto brought in Minnesota would be an “action by information in the nature of a writ of quo warranto.” As Blackstone explains, this action is actually a successor to the original, medieval writ of quo warranto, which worked somewhat differently. The original writ of quo warranto never took root in Minnesota, so our law usually refers to the “information in the nature of a quo warranto” action as, simply, a quo warranto.