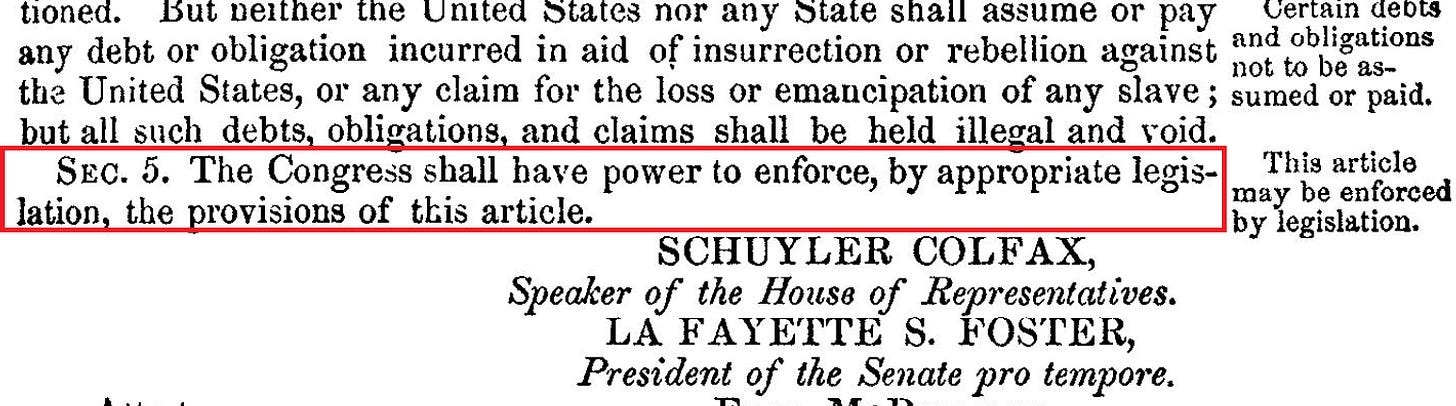

Section Five of Amendment XIV reads:

The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

This was the text confirmed in the Secretary of State’s proclamation when the Amendment was adopted on 28 July 1868. It is the same as the text Congress proposed to the states on 16 June 1866:

However, this is not the text published at the venerable Legal Information Institute @ Cornell, the Georgetown Center for the Constitution, or the Heritage Foundation. They all report that Section Five reads:

The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

They’ve all inserted an anomalous “the” into the text of the amendment! Congress has “power,” not “the power”! This shall henceforth be known as The Misquote.

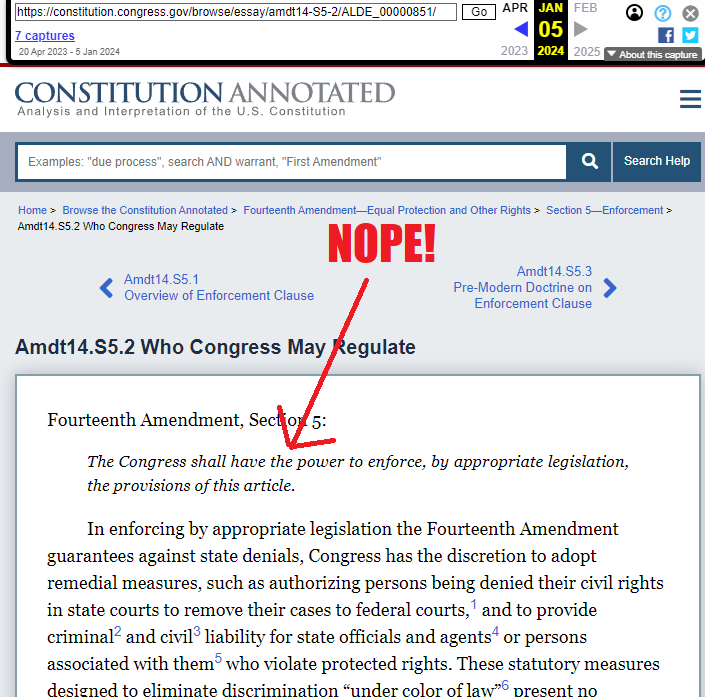

The Constitution Annotated, an official publication of the Library of Congress, lives online at Congress.gov. It is as close to an authoritative record of the Constitution as you can get without going to the National Archives.

Nevertheless, until a couple of weeks ago, the Constitution Annotated had it wrong:

Oh, and guess who else had it wrong? That’s right: the National Archives!

The National Archives (NARA) corrected The Misquote on January 12. Constitution Annotated corrected The Misquote some time after January 6, likely within a day or two of NARA.

With the National Archives’ text corrupted, it’s no surprise that lots of other people have also promoted the Misquote. Here are federal appeals courts in five different circuits that Misquoted Section Five. My Westlaw search1 turned up about sixty-five other instances in federal court decisions alone. I’ve found the Misquote at Reason and a Fifteenth Amendment variant (!) at Vox.

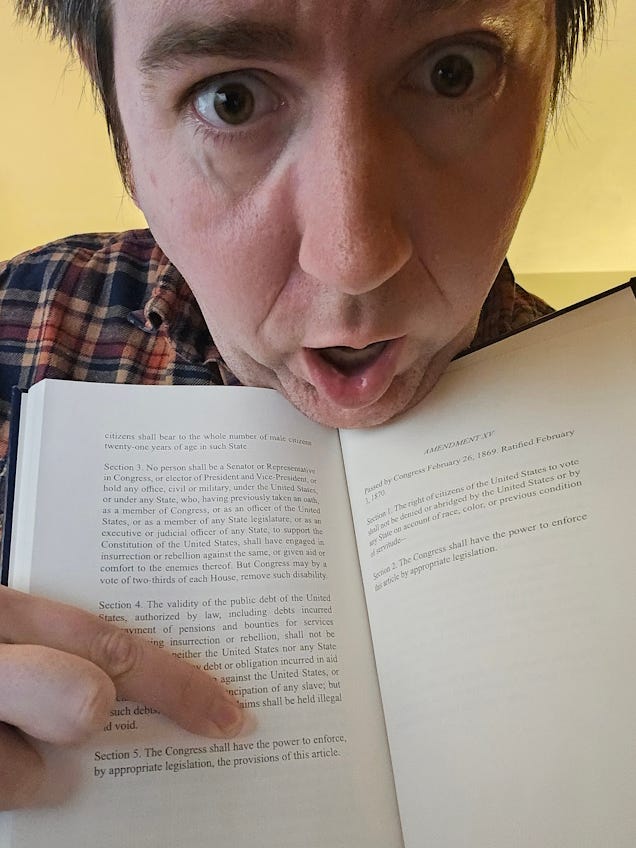

Two of the most important papers about Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment, Blackman & Tillman’s Sweeping and Forcing (p409) and Myles S. Lynch’s Disloyalty and Disqualification (p206), also Misquoted the Fourteenth Amendment. I only know this because I happen to have half a dozen academic papers about Section Three downloaded to my hard drive right now for quick reference.2 I have to imagine that a large portion of the published Fourteenth Amendment literature—hundreds of papers, perhaps?—also include The Misquote. My sister bought me a nice little hardcover Constitution for my birthday (also includes the Articles of Confederation!). Flip it open to Amendment XIV? The Misquote:

How deep does the conspiracy go? Where did the Misquote come from?

Originally, I think it probably came from the failed Equal Rights Amendment. The ERA, as proposed by Congress in 1971-72 (though never3 ratified), actually did use this language: “Section 2. The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.”4 After the ERA’s proposal in 1971, occasional instances of the Misquote began to show up in case law.5 However, references remained scattered—three in the ‘70s,6 four in the ‘80s,7 none in the early ‘90s. Then, suddenly, between July and December 1996, there’s eight Misquotes in federal courts all over the country.8 After that, Misquotes become a regular feature of federal case law.9

Something clearly happened in the middle of 1996. But what?

Well, records of the early Internet are fragmentary, but the middle of 1996 is right around when the National Archives first posted a transcript of the Constitution online. I suspect that, way back in 1996, someone (an intern?) had to type up all the amendments by hand and (perhaps thinking of the ERA?) made a small typo. This being the very early Internet, it was likely posted without the sort of formal vetting process museum websites use today.

Since this was one of the very first Constitutions online, and certainly the most authoritative, the error spread. Lawyers shifted10 to using the National Archives’ version, and the rest is history. The National Archives seems to agree with my guess, though I haven’t spoken with them directly. (Archivists are warmly welcomed in the comments section, though.)

The Misquote was brought to my attention by some very good redditors at the very good /r/SupremeCourt. Biggest thanks to /u/curriedkumquat: to the best of my knowledge, he or she is the first person on Planet Earth to notice The Misquote. To the best of my knowledge, /u/gradientz is the person who got the Library of Congress and NARA to fix it. And /u/Unlikely-Gas-1355 finally got me off my bum to correct my own material.

Because I’m in no position to throw stones, friends! Until late Tuesday night, De Civitate consistently used The Misquote instead of the true text of the Fourteenth Amendment (especially here and here). I have written over a hundred thousand words about the Fourteenth Amendment during the past few months (that’s a full novel!), and I never noticed my mistake. Hey, I depend on Constitution Annotated as much as anyone! Probably more! It’s a fantastic resource!

So is this post just my attempt to bury an embarrassing correction deep in body text whilst grandiosely deflecting blame on as many other people as humanly possible?

Well… Yes! But not just that!

You’re probably thinking I’ve got some substantive angle on this. And I guess I do, kinda.

One of the arguments Donald Trump is using in his defense at the Supreme Court is that the Fourteenth Amendment can only be enforced under legislation passed by Congress, never under legislation passed by states. If Section Five says Congress shall have “the power to enforce” the Fourteenth Amendment, instead of just “power to enforce,” that language does sound a little bit more exclusive of the states than the actual language of the amendment.

I have not yet seen anyone try to build an actual legal argument out of the (imagined) presence of the definite article, but it’s easy to imagine a reader (or Justice?) on the fence about the so-called “self-execution” of Section Three, who then sees the Misquote, thinks it’s real, and that’s what tips the balance away from a correct understanding. It is therefore to the advantage of the Colorado petitioners to fix the Misquote wherever it arises—now that we know about the Misquote! Could the efforts of a few earnest Redditors ultimately tip the justices away from a misreading of Section Five, clarify this issue for the Supreme Court, and change the course of American history?

Probably not! Nobody Reads This Blog™ anyway! The actual point of this post is to tease people!

Because, oh boy, just imagine. Just imagine. You get the call to file an amicus brief at the Supreme Court. Not just at the Supreme Court, either! No, you’re filing in Trump v. Anderson, the most important court case of the year, and a real contender for most important court case of the century. (No mean feat in a century that’s included Obergefell and Dobbs !) The whole country will read this brief. You have the power in your pen to persuade the Nine most powerful people in the country to take your view about an obscure provision of the Fourteenth Amendment; all that stands between you and eternal glory is a few nights of hard work and your well-reputed intelligence.

And then you misquote the Constitution. To the Supreme Court. In the biggest Section Five case since Car 54, Where Are You?

That’s funny. Doesn’t matter if it’s really the National Archives’ fault. It’s still funny. It’d be funny if I did it, it’s funny if you did it.

And, folks, several people did indeed do it:

The Republican National Committee did it on page 14.

Landmark Legal Foundation did it on page 12.

Stephen Yagman11 did it on page 2, in a brief entirely centered on Section Five.

And, of course, the man of the hour himself, Donald J. Trump, did it on page 20 of his cert petition.

As we’ve seen, the National Archives, the Library of Congress, and the Congressional Research Service all fixed the Misquote on their websites around January 12-13 (thanks again to /u/gradientz). Almost immediately after, the Misquote stopped appearing in amicus briefs.12 It’s comforting to know that everyone copies and pastes amendments from the same websites I do.

However, there’s still a few amicus briefs that looked suspiciously like they expected a “the” and were super-confused when they couldn’t find it. Let me give you an example of what I mean. Here’s a passage from the amicus brief of Sen. Ted Cruz and 178 Other Members of Congress:

Congress must pass authorizing legislation to enforce Section 3. The Fourteenth Amendment expressly gives Congress the “power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” U.S. CONST. amend. XIV, § 5

Sen. Cruz has correctly placed “the” outside the quotation marks. That makes this passage not a misquote. Nevertheless, where is his “the” coming from? Why is it there? Delete the “the,” and this passage flows better and more accurately reflects the Constitution’s text. So why type it, unless you expected to find it and didn’t?

The Secretaries of State of [a bunch of red states, not typing them out] did something very similar on page 10 of their amicus brief.

The Republican National Committee did the same thing, but way more suspiciously. Their original brief, from January 5, included the Misquote (p14). Their second brief, filed January 18, included the exact same passage, word-for-word… but subtly moved the quotation marks one word to the right, technically avoiding the Misquote but weirdly, maybe even a little misleadingly (p17). It seems hard to avoid drawing the conclusion that they noticed the Misquote some time after January 5, but decided to fix it without calling attention to it. And, hey, that’s fine! But, again, this story hasn’t been covered anywhere… so who told them?

Wait… does… does the RNC read the /r/SupremeCourt Disqualification Megathread?

I am also The Question tonight. Who would benefit from inserting the definite article in a strategic location within the Fourteenth Amendment in mid-1996?

(Hint: the person on the phone is a National Archives intern!)

There’s more amicus briefs rolling in daily. Meanwhile, even though the government’s websites have now been fixed, there’s still several online authorities claiming there’s a “the” in Section Five! I will continue scanning every new amicus brief for the words “power to enforce,” hoping for an excuse to grin. I’ll update this post if anyone else slips up.

Meanwhile, one more big round of applause for /u/curriedkumquat, /u/gradientz, and /u/Unlikely-Gas-1355, eh? What a find! You did it, Reddit!

UPDATE (a few hours after publication): Redditor /u/pm_me_your_cocktail disagrees with my position that the Misquote has no serious legal impact:

There is some skepticism in the comments about whether this correction matters. I want to impress on people: this is a big fucking deal. Legal construction, including constitutional interpretation, can often turn on the presence or absence of a grammatical determiner or the use of the definite article ("the"). As the word "the" is defined in Black's Law Dictionary 1477 (6th ed. 1990):

In construing statute, definite article `the' particularizes the subject which it precedes and is word of limitation as opposed to indefinite or generalizing force `a' or `an'.

And courts regularly interpret "the" to imply exclusivity. For instance, SCOTUS in Freytag v. Commissioner, 501 U.S. 868 (1991):

The [Appointments] Clause does not refer generally to "Bodies exercising judicial Functions," or even to "Courts" generally, or even to "Courts of Law" generally. It refers to "the Courts of Law." Certainly this does not mean any "Cour[t] of Law" (the Supreme Court of Rhode Island would not do). The definite article "the" obviously narrows the class of eligible "Courts of Law" to those courts of law envisioned by the Constitution. Those are Article III courts, and the Tax Court is not one of them.

The D.C. Circuit, in a widely-quoting passage in American Business Association v. Slater, 231 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir. 2000) (quoting Brooks v. Zabka, 168 Colo. 265 (1969) (en banc)):

"'[I]t is a rule of law well established that the definite article ‘the’ particularizes the subject which it precedes. It is a word of limitation...'"

The rule has long popped up in all kinds of contexts in state courts, as in Fairbrother v. Adams, 135 Vt. 428 (1977):

The language of the deed used the definite article "the", which implies exclusivity.

And not to be too on the nose, but this from less than a year ago in the Texas Supreme Court, addressing the specific phrase "the power" in TotalEnergies E&P USA v. MP Gulf of Mexico (Texas 2023):

[A contrary construction] gives inadequate meaning to the rule's declaration that the arbitrator "shall have the power to rule on . . . any objections with respect to the . . . arbitrability of any claim or counterclaim." Our conclusion might be different if the rule provided that the arbitrator "may have the power," or that the arbitrator "shall have power," but the rule in fact provides that the arbitrator "shall have the power." The verb "shall" in this sentence "evidences the mandatory nature of the duty imposed."... And the use of the definite article "the" with the singular noun "power" indicates exclusivity, limiting the delegation of "the power" to the arbitrator.

That is not to say that 14A s5 would or should have been interpreted in that fashion. But if the Constitution said "the power" instead of simply "power" it would be a reasonable argument in favor of Congress's power (as intended by the framers of the 14th Amendment, and as understood by the public at the time of its debate and adoption) being exclusive. Not necessarily a dispositive argument, but certainly a cogent argument and the kind of textual clue that could make or break an analysis. Bravo to u/curriedkumquat for discovering this 3-decade mistake, and to u/gradientz for seeing that it was promptly fixed.

Edit to add: The earliest SCOTUS case I have found discussing the importance of "the power" versus an articleless "power" in the Constitutional text is the famous 200-year-old case Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824), in which the Court held that the federal government has exclusive power over interstate commerce. In concurrence, Justice William Johnson noted:

The words of the constitution are, "Congress shall have power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes." It is not material, in my view of the subject, to inquire whether the article a or the should be prefixed to the word "power." Either, or neither, will produce the same result: if either, it is clear that the article the would be the proper one, since the next preceding grant of power is certainly exclusive, to wit: "to borrow money on the credit of the United States."

In that case J. Johnson found other prudential and legal-historical clues to show that Congress's power over interstate commerce was exclusive. But it is notable that the absence of the word "the" was important enough to raise, even if only to immediately dispose of it.

This was such a good comment that I wanted to put it in front of you readers. I had never heard of any of these cases. (Okay, I did graduate high school, so I knew Gibbons v. Ogden, but not the rest!) This persuades me that the misquoted “the” could be a big deal, especially if the misquote went uncorrected. When I posted this article, I didn’t believe the “the” really had any substantive impact at all.

I still don’t think it will make a material difference in Trump v. Anderson specifically, because none of the briefs have attempted this argument, and only one amicus (the Brief of Twenty-Five States & Bits of Arizona and North Carolina) mentioned any of the cases /u/pm_me_your_cocktail mentioned (Freytag, on a different point).

On the other hand, maybe Anderson’s legal team can make something out of the fact that there isn’t a “the”?

EDITOR’S NOTE: I also added links to Reason and Vox in body text, and, for posterity (and/or some legal intern from 2087 here to write a footnote about why a bunch of turn-of-the-millennium documents misquote the Constitution), here is a link to /u/curriedkumquat’s very first comment on this topic. (Plus an Archive/Wayback link, ‘cause I estimate a <5% chance Reddit is still online in the 2080s.)

UPDATE 1 February 2024:

Amicus briefs against Trump were due yesterday, and, lo and behold, there was some more action on the “the” front!

Brian J. Martin did it on page 11.

Professor Kermit Roosevelt technically did not do it on pages 5 & 8, but only because he didn’t use quotation marks.

On the other hand, several people got it right:

First: A group of retired state supreme court justices (including Minnesota’s own Paul Anderson) not only quote Section 5 correctly on page 8, but they also call out the Misquote in a footnote:

Section 5 is occasionally misquoted as “Congress shall have the power.” If anyone might misinterpret “the” power as meaning exclusive power, the fact that Section 5 does not say that refutes the argument.

They provide no citation for this fact, so I will choose to believe that they learned about it by reading De Civ.

Second: Conservative judge J. Michael Luttig (who strenuously defended Trump on technical grounds during the second impeachment) filed an amicus (with several other conservative former officials) supporting the Colorado Supreme Court. On pages 8 & 9, he actually makes an argument based on the absence of “the” in Section Five:

Section 5 states: “The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” (Emphasis added). Nothing in these fifteen words deprives the states of their pre-existing power, subject to this Court’s review, to adjudicate a presidential candidate’s constitutional qualifications. See Part I.A., supra. Section 5 says “power,” not “the power”—much less “exclusive” or “sole power.” Compare Art. I, § 2, cl. 5, and § 3, cl. 6. (“the sole Power”); Art. I, § 8, cl. 17 (“exclusive Legislation”).

Third: David B. Tatge, a private lawyer from Virginia, raises a similar argument on page 21:

Nowhere does this language say that “only” the Congress shall have enforcement rights. Nor does Section 5 say that Congress shall have “the” power to enforce Section 3. (In fact, as discussed later, state courts have enforced Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment for years, via their various state election and quo warranto laws.)

I am reassured that I did not jeopardize the case by failing to file an amicus brief of my own. My further thanks to /u/gradientz and /u/Unlikely-gas-1355 for calling my attention to the Luttig and Martin briefs.

That’s right, I have (limited) Westlaw access now. FEAR MY POWER!

The trick, by the way, is to convince Westlaw not to ignore the word “the,” which it naturally wants to filter out of your search. I was able to force it to deliver the correct results using this search string:

adv: "shall have the power #to enforce, #by appropriate legislation, the provisions #of #this article"

I am referring only to the most recent drafts posted to SSRN. Articles may be corrected upon actual publication, or subsequently. Meanwhile, credit where it’s due: Kurt Lash’s Meaning of Ambiguity of Section Three, Baude & Paulsen’s Sweep and Force, and Mark Graber’s Our Questions, Their Answers all quoted Section Five correctly.

Some people insist today that the ERA could still be revived, without being proposed again by Congress and re-ratified. These people are lawless vandals.

To impose the ERA after its deadline expired—and it certainly did expire, no matter what story they spin you about “prefatory clauses” being somehow amendable by statute—would be, legally speaking, absolutely the same thing as Mike Pence getting up to the lectern on January 6, 2020, refusing to count the electoral votes for Biden, and declaring Trump re-elected. Even the original purported “extension” by Congress in 1978 (giving the ERA until 1982), was without legal foundation, and would not have been valid if it had succeeded in scaring up additional ratifications. ERA revivalists and J6’ers deserve each other, because they both operate by the same fundamental principle: “the law must be whatever I want it to be, and I will find a law professor somewhere to torture the law until I can pretend its broken shell is really on my side.” This is one reason why I can’t take Democrats’ opprobrium against the election deniers in Congress very seriously (despite my own harsh words for them); the Democrats (and some Republicans) are no better.

If Trump had managed to re-install himself by purportedly “legal” action using a rogue Congress and a rogue White House, the correct response among states would have been to ignore the Trump “presidency,” by violence if necessary, and to treat the Presidency as sede vacante. The same response will be appropriate should the ERA ever be imposed without re-proposal by Congress and re-ratification by all necessary states. (The states that ratified the ERA then rescinded ratification, which ERA revivalists dismiss out-of-hand as invalid, only add to the moral insult: revivalists want to impose the ERA as the “Will of the People” by including ratifications from states whose people explicitly do not consent to be counted.)

Fortunately, as in the Trump election-heist attempt, the courts have done a great job holding the line against the barbarians. Idaho v. Freeman surely deserves to have been affirmed and passed down as precedent, but was mooted by the deadline’s expiration (which no one imagined questioning at the time). Virginia v. Ferriero and its affirmation (though rather weak-kneed) will have to do for the time being.

The original ERA proposal, in 1923, did not include the “the,” and was modeled more closely on the enforcement clause of the Thirteenth Amendment rather than the Fourteenth’s. According to the CRS—which is a great research service but which is also partly responsible for The Misquote, so take it with whatever grain of salt you need to—the ERA switched to concurrent-enforcement language reminiscent of the 18th Amendment in 1943, then kept that language all the way up until 1971.

So it really was Representative Martha Griffiths, or one of her close colleagues, who decided to copy the Fourteenth Amendment’s enforcement clause and add a “the” to it. Which is fine! The ERA can say and do what it likes! But it seems to have led people to start confusing the ERA’s language with the language in the Fourteenth Amendment.

There’s also a single, isolated misquote in a 1965 decision called U.S. v. County Board of Elections of Monroe County, New York, 248 F.Supp. 316. This may just be a fluke, or it may be evidence of an earlier origin for the “Congress shall have the power” formulation.

Oh, bugger, this is original research so I have to actually CITE these, don’t I? Agh. Okay. The 1970s:

Com. of Pa. v. Local 542, Intern. Union of Operating Engineers, 347 F.Supp. 268 (1972)

Blake v. Town of Delaware City, 441 F.Supp. 1189 (1977)

Greene v. City of Memphis, 610 F.2d 395 (1979)

Several other 1970s (and 1980s) cases, like 1978’s Nevada Supreme Court decision Kimble v. Swackhamer (incredible name!), actually did deal with the Equal Rights Amendment, but will show up in your search results anyway.

The 1980s cases:

Kenny v. Board of Trustees of Valley Cty. School Dist. Nos. 1 and 1-A, 543 F.Supp. 1194 (1982)

Taylor v. Gilmartin, 686 F.2d 1346 (1982)

Tonya K. By Diane K. v. Chicago Bd. of Educ., unreported in F.Supp., 1987 WL 14699 (1987)

There were zero cases I found between 1987 and June 1996, then, suddenly, WHAMMO! 1996 looks like this:

Walden v. Florida Dept. of Corrections, 975 F.Supp. 1330 (June 24, 1996) (Tallahassee, FL)

In re Headrick, 200 B.R. 963 (September 26, 1996) (Augusta, GA)

Genentech, Inc. v. Regents of University of California, 939 F.Supp. 639 (September 27, 1996) (despite the caption, Indianapolis, IN)

Mayer v. University of Minnesota, 940 F.Supp. 1474 (October 15, 1996) (Minneapolis, MN)

Rouser v. White, 944 F.Supp. 1447 (October 28, 1996) (Eastern District of California)

Teichgraeber v. Memorial Union Corp. of the Emporia State University, 946 F.Supp. 900 (November 26, 1996) (Kansas)

College Sav. Bank v. Florida Prepaid Postsecondary Educ. Expense Bd, 948 F.Supp. 400 (December 13, 1996) (New Jersey)

In re Burke, 204 B.R. 493 (December 16, 1996) (Augusta, GA) (but not the same judge as the ones who did the Misquote in In re Headrick on September 26).

I’m sorry; I’m not listing these all out for you. There’s dozens. I linked a few earlier in this article.

It’s a good bet that some of them had previously used the copy of the Constitution hosted by the House of Representatives itself, or one of the other far-less-official Constitutions online at the time. None of them included the Misquote. But the National Archives is the official home of the Constitution, so of course people would start using it instead of the Constitution as transcribed by MidnightBeach.com.

Technically, Yagman’s client, William Jones, should be credited with this L, but Jones appears to just be a random person from California, not a lawyer, who wanted to shoulder into this case (don’t we all, William Jones? don’t we all?) and we should therefore not rag on him.

Yagman, however, was said to have “a formidable reputation as a plaintiff’s advocate” by no less than Chief Judge Alex Kozinski of the Ninth Circuit (according to Yagman’s fawning Wikipedia entry), so you can definitely rag on him.

Credit where it’s due: the only amicus to correctly quote Section Five before the Misquote was corrected was the Brief of Indiana, West Virginia, 25 Other States, and the Arizona Legislature, which was filed on January 5 but still got it right. Kudos!

I am happy to say that my two "pocket" editions of the Constitution -- Bantam Classic (1998, reissued 2008) and U.S. Capitol Historical Society (no publication date printed) -- have the correct text. Jonathan Swift's remark, "Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it," was a prophetic statement about the Internet. (BTW, there are various versions of this quote, referring to the truth putting on its boots etc., that have been falsely attributed to Mark Twain -- he at least survived into the 20th century, while Swift said it in 1710.) The internet is also a dandy way to make the misattribution of quotes to famous people all but universal...

Ah, but my more serious hardcover book, The Heritage Guide to the Constitution (The Heritage Foundation 2005), has the misquote. Et tu, Heritage?

Nice soyjak face