NOTE: A much shorter, more sedate version of this article was recently published by The American Conservative. If you just want the highlights of this article, in relatively temperate terms, start there.

Some scholars believe that a legal right to abortion is not just a good idea; they think the Constitution guarantees a legal right to an abortion.

These arguments, are, for the most part, very silly. They do not point to a constitutional provision that says, “The right to an abortion shall not be infringed,” because, of course, there isn't one, and no amendment saying so would have a prayer of passing today or at any time in the past. Instead, virtually all these arguments depend on "penumbras" or "substantive liberty interests" or "correlates of equal protection." These tools allow Professors of Law to scry unwritten rights in the Constitution in much the same way that Roman professors of haruspicy once scried omens in sheep intestines. This approach can discover anything in the Constitution a judge might desire to find—and, of course, always does. Under Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, American abortion law was built on precisely this type of wishcasting, plus a gluttonous amount of ipse dixit (the ancient legal maxim “because I said so”), and absurd abuses of the otherwise-sound principle of stare decisis.

Professor Andrew Koppelman (who last appeared on De Civitate just over a decade ago) is nearly the sole exception. He proposes that, in fact, the Constitution's text does contain a clause which, under its original public meaning, guarantees an abortion right. That clause is the Thirteenth Amendment, proposed and ratified in 1865, which reads:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

That’s right: according to Koppelman, the constitutional amendment that enacted Lincoln’s promise to make oppressed Black people “thenceforward and forever free” simultaneously ensured that unborn children would be thenceforward and forever oppressed.

Koppelman has been making this argument for nearly as long as I’ve been alive, in three separate papers: Forced Labor (1990), Forced Labor Revisited (2010), and Originalism, Abortion, and the Thirteenth Amendment (2012).1 As Koppelman is the first to admit (in Forced Labor Revisited ‘10), few have ever taken his argument very seriously, even on his own side.2 Nonetheless, Professor Koppelman suggests that two decades of everyone ignoring his argument probably means he’s right. He then adds:

Perhaps you, reading this right now, don't buy the argument. If so, I wish you would write to me and explain why. If there is a defect in the argument, no one has ever stated it in print. Hit me. I want you to.

I’ve been there myself, screaming into a silent void even though I’m clearly right. It’s maddening. No one should have to suffer like that.

Now, I am not a Professional Lawyer. I lack the time, resources, Westlaw subscription, credentials, and professional incentives to write a proper law review article for a peer-reviewed journal. (As long as this article looks, it’s not even as long as the first of Koppelman’s three papers on this topic.) My main legal qualification is my love of footnotes.3 However, since Koppelman has made this invitation, I’d like to offer some limited reply. Future writers might then be able to build on this, but, hopefully, this Blog Post provides a few useful takeaways, even in its current form.

I think this is important, because Koppelman’s is by far the best constitutional argument for abortion rights I’ve ever seen, and I’ve thought so since I encountered it in 2009. Koppelman’s argument for a constitutional right to abortion is the only one I’ve seen that’s actually an argument, not haruspicy.4 I think it’s wrong, and decisively so—but it is, at least, an argument.

Now that Roe has fallen, we can expect to see the “Thirteenth Amendment argument” making the rounds as abortion supporters are finally forced to try grounding their desire for a constitutional right to abortion in the actual Constitution, rather than… whatever Roe was doing. Koppelman himself notes the manifold failures of Roe in his introduction to Forced Labor ‘90.

Also, since no one has previously written an extended reply to Koppelman, I need to write one, or I will lose a side argument on Twitter.5

Koppelman’s Textual Argument (“Argument A”)

Professor Koppelman's primary argument, which he refers to as his “libertarian” argument, runs like this:

Involuntary servitude is unconstitutional. (from Amendment XIII)

The essence of involuntary servitude is “that control by which the service of one [person]6 is disposed of or coerced for another’s benefit” (quoting Bailey v. Alabama (1911)).

Abortion prohibitions mandate “forced pregnancy and childbirth.”

“Forced” pregnancy and childbirth “compel… the woman to serve the fetus,” which (from A2) constitutes that essence of involuntary servitude.

Therefore, abortion prohibitions mandate involuntary servitude. (from A3 & A4)

Therefore, prohibiting abortion is unconstitutional. (from A5 & A1)

Koppelman’s Original Meaning Argument (“Argument B”)

Koppelman makes a secondary argument, revolving around the “badges and incidents” of slavery, which he refers to as his “egalitarian” argument:

The Thirteenth Amendment, as it would have been originally understood, was intended to and did in fact grant Congress plenary power to outlaw not only “all forms of slavery and involuntary servitude, but also to eradicate the last vestiges and incidents of a society half slave and half free” (quoting 1968’s Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.).

The “principal utility to the slaveholding class” of “black women of childbearing age” was their “ability to reproduce the labor force.” As such, they had no sexual freedom, even “through abstinence,” and were often “raped with impunity.” They were treated as “procreative vessels,” “reduc[ed] to sexual object[s]… to be raped, bred, or abused,” and “faced constant, coercive inducements to bear children.” The details,7 as always when one looks honestly at American slavery, are harrowing.

Given this history, “loss of control over... reproductive capacities” should be understood as “the state-enforced creation of the very indignity that enslaved women suffered.”8

Therefore, “loss of control over reproductive capacities” is a “badge, vestige, and incident of slavery,” which violates the original public meaning of Amendment XIII. (from B3 & B1)

Abortion prohibitions mandate “loss of control over reproductive capacities.”

Therefore, abortion prohibitions violate Amendment XIII. (from B4 & B5)

Is that a fair summary, Professor? One necessarily loses many subtleties and important distinctions when one summarizes 105 pages of law review articles into a dozen points, so I encourage you to read them yourself.9 I believe these claims are his bottom line, and I also think they are the strongest possible versions of his bottom line. This is a crisp, clear argument based on plenty of historical evidence, several important Supreme Court precedents, and the two guiding stars of sound legal construction: the literal meaning of the dead text, and the original understanding of that text by the public that debated and finally received it. Two cheers for Professor Koppelman.

Before coming to the meat of the Thirteenth Amendment argument, however, it will be profitable to consider two threshold issues: fetal personhood and violence.

The Argument Concedes Fetal Personhood

Let’s start here, because it’s short and sweet and perhaps too clever by half.

Professor Koppelman does not believe fetuses are persons in a moral sense. He concedes that, if the fetus “is in fact a person, a being with rights that others are bound to respect,” then it puts important parts of his argument under immense strain. Nevertheless, he insists that his argument “makes its constitutional case without any direct reliance on the position that a fetus is not a person.”10

Well, he’s right about that: his argument doesn’t rely on the position that the fetus is not a person. In fact, Koppelman’s argument relies on the position that the fetus is a person.

Koppelman’s argument (at A2) says that the essence of involuntary servitude is “that control by which the service of one [person] is disposed of or coerced for another’s benefit.” Specifically, he says that abortion prohibitions coerce the service of one person—the mother—for the benefit of another person—the fetus. Either the fetus is a person for the purposes of the U.S. Constitution (or at least the Reconstruction Amendments), or Koppelman’s entire Argument A collapses. If we accept that the fetus is a person for constitutional purposes, that keeps Koppelman’s argument alive, but it has enormous implications, given the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantee of a right to “life” and "equal protection" for all “persons”.11

Koppelman recognizes these implications and tries to resist them. (We are about to go down a little bit of a rabbit hole. If you get dizzy at any point here, you can skip ahead to the next section.) Koppelman writes, in footnote 136 of Forced Labor ‘90:

Although it is because the fetus is recognized to be an entity separate from the woman that a law prohibiting abortion violates the Thirteenth Amendment, by compelling her to serve another’s private interests, this argument does not presuppose that the entity the woman is serving is a person. [In the seminal involuntary servitude case, Bailey v. Alabama,] Bailey, after all, was being compelled to serve a corporation, the Riverside Company, rather than a natural person. When Bailey was decided in 1911, the company was certainly protected as a “person” by the equal protection clause of the fourteenth amendment, see Santa Clara County v. Southern Pac. R.R., but this only shows that the concept of “personhood” is a complex one: an entity may be a person for some legal purposes but not others.

This defense does not strike me (the layman) as terribly persuasive. Indeed, it’s confusing, and, the more we look at it, the more confusing it gets.

It is true that there are associations that we count as “people” (or “juridic persons”) even though they aren't actually living, breathing individuals (“natural persons”). These associations include clubs, unions, corporations, trusts, monastic orders, and nation-states, among others. They are considered people under the law because the legal fiction of a “juridic person” is a useful, convenient way for actual people to exercise their rights and duties under law. Juridic persons are extensions of natural persons. As Blackstone explained in his famous Commentaries, several years before the letter “s” led its bloody war of conquest against the letter “f”:

…as the neceffary forms of invefting a feries of individuals, one after another, with the fame identical rights, would be very inconvenient, if not impracticable; it has been found neceffary, when it is for the advantage of the public to have any particular rights kept on foot and continued, to conftitute artificial perfons, who may maintain a perpetual fucceffion, and enjoy a kind of legal immortality… in order to preferve entire and for ever thofe rights and immunities, which, if they were grated only to thofe individuals of which the body corporate is compofed, would upon their death be utterly loft and extinct.

Thus, we do not (and cannot coherently) confer juridic personhood on, say, a bag of white rice, or the abstract concept of calculus. Personhood is for actual persons and associations of actual persons.

Koppelman seems to be saying in his footnote that the fetus is, for Thirteenth Amendment purposes, not a natural person but a juridic person. This seems incoherent. If the fetus is a juridic person—some kind of “association” of natural persons which collectively exercises rights on their behalf—what can this even mean?12 If the fetus has limited personhood (in Koppelman’s argument) only because it is extending the rights of some community of natural persons… which natural persons are they?

Is Koppelman suggesting that the limited juridic fetal personhood he recognizes is a stand-in for the future natural person who (in Koppelman’s view) will come to exist only at birth? He seems to suggest this in an aside about Griswold at the end of footnote 136, where he contends (I think) that a State which banned contraception might be holding women in involuntary servitude to a future person.

This seems bizarre. To the best of my (layperson) knowledge, juridic personhood is exercised on behalf of currently living or deceased natural persons; I am aware of no case where juridic personhood is exercised on behalf of natural persons who have not yet come into being. The closest parallel I’m aware of is in inheritance law, but that runs counter to Koppelman’s argument: in inheritance law, the unborn child en ventre sa mere is “entitled to all the privileges of other persons,”13 but a (potential) child not yet conceived has no claim on anyone whatsoever, unless the potential child's prospective parents expressly impose such a claim on themselves (which is an exercise of their own rights, not the child’s).

Insofar as Koppelman’s argument is an originalist argument, it would seem that he must also contend that this odd view of fetal personhood was held by some plausible version of “the public” in the 1860s. This seems challenging. However, it is possible that I am not understanding his “aversive originalism” correctly.

Regardless, it seems that, for Koppelman’s argument to work at all, he must concede, as table stakes, that, from the time of conception14 forward, the fetus is a natural human person within the meaning of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. Koppelman is very smart and more educated than I am. It’s possible he sees some way out of this quandary. But would his escape route cut through too much of the rest of his argument to hold it intact?

(Even if we accept Koppelman’s odd apparent view that fetuses are not natural persons, but limited juridic persons for constitutional purposes, this would still mean quite a revolution in abortion law. Juridic persons do not necessarily have a right to continued existence, but they have a variety of other rights and duties, including the right to have their interests represented in court and the right to equal protection under law. The pro-life movement could easily spend the next decade exploring the boundaries of those personal fetal rights in state courts.)

For most abortion arguments, the concession of fetal personhood would be fatal. As Roe v. Wade stated, “If the suggestion of personhood [under the Fourteenth Amendment] is established, the appellant’s case [seeking to establish abortion rights], of course, collapses.” However, Koppelman believes that his argument still holds up if the fetus is a person. I agree. The Thirteenth Amendment outlaws involuntary servitude universally. No person may hold another person in involuntary servitude. If abortion prohibitions hold mothers in involuntary servitude, then, as a legal matter, abortion prohibitions must fall—even though the mothers’ unborn children are persons. The concession that fetuses are persons puts large portions of Koppelman’s argument under severe strain, as Koppelman acknowledges. Other areas, where Koppelman depends on the ambiguity of fetal rights, are simply obliterated (like his claims about the burden of proof in Forced Labor Revisited ‘10). However, his core argument is untouched.

Before we move on, though, I wish to suggest mildly that the ease with which Koppelman intuitively recognized the fetus’s capacity to legally function as a natural person, building a hundred-page argument premised on fetal natural personhood and defending it for thirty years without ever really apparently noticing that he’d done that, is perhaps most easily explained by the possibility that the fetus actually is a natural person—and that, at least at a subconscious level, this is obvious to everyone with eyes to see, ears to hear, and a basic knowledge of modern embryology. It is very easy to accidentally slip into the idiom of talking about a fetus as a human person because, well, what else is she? A toenail? An alien? Legally speaking, her rights and duties are closely akin to those of a newborn.15 Whenever he considers the possibility of fetal personhood, Koppelman parades horribles at us,16 but this sort of fear has always led to the ugliest prejudices.

We should also note, in passing, that one of Koppelman’s motivations for developing the Thirteenth Amendment argument in the first place was to deliver a “constitutional case [for abortion rights] without any direct reliance on the position that a fetus is not a person.” He has succeeded in doing this, but only by conceding the position that the fetus is a person—at the very least a juridic person, and in all likelihood a natural person. This concession is a cost few pro-choicers are willing to pay. I think Koppelman has no choice but to do so, as must anyone else who advances a Thirteenth Amendment argument. However, for now, the core of his argument remains intact. We soldier on.

Abortions Are Violent

Even if Koppelman’s argument is correct on every point from here on out, it would not justify abortion as it is typically practiced in the United States today. Libertarian arguments for abortion, including Koppelman’s, typically present it as something akin to an eviction. “You are no longer welcome on my property / in my body / to my labor, so I will now compel you to leave.” If you evict someone from your house and he freezes to death on the street that very night, well, that’s not your problem (says the libertarian). By the same token, if you evict a fetus from your womb and he can’t survive in the outside world, again, that’s sad, but also not your problem.

On the other hand, suppose you submit a written notice of eviction to an elderly tenant whom you know to be blind. He's also disabled, and unable to leave his second-story unit unless physically assisted on the stairs.17 When the tenant fails to vacate the premises (because he can't read the eviction notice, thus has no idea you've evicted him, and couldn't leave even if he did), you enter his room, inject him with deadly poison, then dismember him, finally chucking the bloody limbs of his corpse out an upstairs window without ceremony.

Even the libertarians are going to put you in jail for murder!

It is possible to imagine an abortion procedure that looks something like the libertarian dream, where abortion is “merely” a deadly eviction, not a murder. In such a procedure, the fetal “tenant” would be extracted with something like a C-section or induced labor and given some reasonable degree of medical care, even some token amount of futile care. The fetus, if and when she dies, would then be treated like a human being, death and birth certificates filed, funeral arrangements made (by the State if the mother is unwilling). Naturally, an important government and medical priority in this world would be to develop technology to push back the frontiers of viability to very early dates, eventually culminating in the old sci-fi fantasy of artificial wombs where unwanted children can gestate safely without inconvenience to their mothers.

Abortion in the United States does not resemble this. Surgical abortions are unbelievably violent. A dilation & extraction literally tears a fetus limb-from-limb and tosses them out one bit at a time. A dilation & curettage stabs the fetus to death, then dismembers her and “scoops” the mutilated corpse out. An aspiration abortion uses a vacuum to dismember the fetus. The kindest version of abortion we have uses digoxin to poison the fetus, killing her prior to dismemberment. This is typically only used on fetuses capable of directly experiencing pain, but abortion providers are reluctant to use it, because digoxin limits the resale value of the fetal body parts.

The closest thing we have to the libertarian “eviction model” of abortion is chemical abortion (called by advocates “medical abortion”) using misoprostol. Misoprostol induces labor, physically expelling the fetus from the uterus at a stage of pregnancy too early to survive—a straightforward “eviction.” Unfortunately, our chemical abortion protocol precedes the misoprostol with mifepristone, administered 1-2 days prior to the misoprostol. The mifepristone kills the fetus in the womb by cutting off its food and air supply prior to expulsion.

This is akin to murdering your tenant by refusing to allow DoorDash to come in so he starves and then also suffocating him by sucking all the air out of his room, then “evicting” the corpse on a stretcher. I’d rather be quietly suffocated than dismembered, I suppose, but you’re still going to libertarian jail for murder.

You can’t cut the mifepristone out of the protocol, either, because the whole point of chemical abortion is to allow mothers to “evict” their fetuses at home, on the toilet, with no need for any medical professionals to be around to care for the newborns when they come out. The fetuses therefore have to be killed in utero; if born alive, they would need medical care, and medical abortions could no longer happen at home.18

Abortion, as it is practiced today, is far more violent—and deliberately violent—than even the ugliest eviction process.

In my experience, libertarians typically wriggle out of this difficulty by retreating from it. They were trying to show that abortion is justified even if the fetus is a person. However, now that they see abortion is it is practiced today involves a great deal of unnecessary (and therefore unjustified) violence, they fall back to their real position that the fetus is not a person, so the violence doesn’t count.

However, Koppelman and others taking this approach are unable to make that retreat. As we’ve seen, the Thirteenth Amendment argument requires its supporters to accept the natural personhood of the fetus. Even if supporters continue to resist this conclusion, a major strength of the Thirteenth Amendment argument is that it is at least compatible with belief in the natural personhood of the fetus. Yet the version of abortion that the argument actually defends is not a version of abortion that exists in the present United States.

Nevertheless, it is possible to imagine a version of abortion that fits the Thirteenth Amendment argument, and we can still engage with that. Let’s finally get into the meat of the Thirteenth Amendment argument.

The Argument Proves Too Much

Your first reaction to the Thirteenth Amendment argument—Argument A especially—might be that it seems to prove too much. (That was John McGinnis’s reaction, as well as Michael Stokes Paulsen’s.)

Koppelman claims (in A1) that involuntary servitude is unconstitutional, and he claims (in A2) that involuntary servitude is defined as

that control by which the personal service of one [person] is disposed of or coerced for another’s benefit.

He provides some alternate definitions, all drawn from important court cases, to drive the point home: “involuntary servitude” is also defined as:

the control of the labor and services of one man for the benefit of another, and the absence of a legal right to the disposal of his own person, property and services (Plessy v. Ferguson)

and:

a condition of enforced compulsory service of one to another. (Hodges v. U.S.)

Koppelman claims that anything which fits these definitions constitutes involuntary servitude, that “coerced pregnancy” (FLR ‘10, p4) fits all these definitions, and that “coerced pregnancy” is therefore unconstitutional “involuntary servitude.”

However, we live in a society where able-bodied men can be conscripted into the military. Many of our grandfathers were conscripted. The military exercises absolute “control of the labor and services” over conscripts for the benefit of others, including their fellow citizens, the nation itself, the commander-in-chief, the military as a whole, or the conscript’s immediate superior officer. This appears to be “involuntary servitude,” if we accept Koppelman’s definition without further modification.

Koppelman resists this inference. In Forced Labor '90 (p519), he argues:

...the duties of citizenship, however burdensome, are inescapable conditions of freedom. A person cannot be a slave if he is as free as it is possible for a citizen to be. If "involuntary servitude" is defined as compulsory service to another private individual, as opposed to service to the state which guarantees civil liberty, then conscription for public duties simply falls outside the definition.

I don't think this quite grasps military service. If Lieutenant Smith orders Private Jones to get Lieutenant Smith a cup of coffee, purely for Smith’s benefit, Jones had better do it lickety-split or face prison for disobeying a direct order. One might argue that Smith's order is improper, because it does not “relate to military duty,” but good luck with that: the Manual for Courts-Martial (2019 ed., p331) states clearly that all orders are presumptively lawful and are "disobeyed at the peril of the subordinate" unless "patently illegal."

Let’s look at the structure of military service in light of Bailey v. Alabama (1911), a crucial Thirteenth Amendment case on which Koppelman heavily relies. His summary of the case is solid:

The case came to the Supreme Court as an appeal from a criminal conviction for fraud. Bailey, a black laborer, had accepted a fifteen dollar advance for signing a contract in which he agreed to work for a landholding corporation, the Riverside Company, for a year. Under the contract, he would earn twelve dollars a month, of which $1.25 would be deducted each month to repay the fifteen dollar advance. After about a month, Bailey left the job and refused to return to it. He then was prosecuted for defrauding the Riverside Company of fifteen dollars, convicted, and sentenced to 136 days of hard labor. While there was no evidence that he had intended to defraud the company, an Alabama statute provided that if one breached a service contract without refunding the money paid, fraud would be presumed. Under state rules of evidence, the accused was not permitted to testify about his intentions for the purpose of rebutting the presumption.

In reversing the conviction, Justice Hughes declared that “[w]ithout imputing any actual motive to oppress, we must consider the natural operation of the statute here in question, and it is apparent that it furnishes a convenient instrument for the coercion which the Constitution... forbid[s].” The thirteenth amendment, he concluded, “does not permit slavery or involuntary servitude to be established or maintained through the operation of the criminal law by making it a crime to refuse to submit to the one or to render the service which would constitute the other.”

We must consider the natural operation of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, the Manual of Courts-Martial, and the fundamental military presumption that orders are lawful. Without imputing any actual motive to oppress,19 the natural operation of these authorities working in concert clearly furnishes a “convenient instrument for the coercion which the Constitution… forbid[s],” and that instrument is indeed “maintained through the operation of the criminal law by making it a crime to refuse to submit.”

For much of our nation’s history, able-bodied men were also subject to the entire trinoda necessitas. This meant that the State could—and did—force men to leave their homes and livelihoods for some period of time to build roads and bridges, all without pay. In Butler v. Perry, the 1916 case upholding this practice under the Thirteenth Amendment, the rule was that Floridians had to devote six ten-hour days out of every year to uncompensated road-building or face criminal penalties. This appears to be “compulsory service for another’s benefit.”

Again, Koppelman tries to resist this, by arguing that “the duties of citizenship, however burdensome, are inescapable conditions of freedom. A person cannot be a slave if he is as free as it is possible for a citizen to be.”

Yet is a person under the trinoda necessitas as free as it is possible for a citizen to be? I’m a citizen, and I’m free, and I am not subject to the road-building draft. Nobody has been subject to the road-building draft in decades. Why? Cities and states decided to start paying for construction crews, instead of relying on the unpaid, involuntary labor of private citizens. The State could have done this all along. It chose not to. As the past hundred years have proved, compulsory road-building service is not and never has been an “inescapable condition of freedom.” Nonetheless, in Butler v. Perry, even as the trinodas was waning nationwide, the Supreme Court upheld it against a Thirteenth Amendment claim. It is also possible to imagine an all-volunteer military, or volunteer jury duty… yet here we are.

If we adopt Koppelman’s definition of “involuntary servitude” from Argument A2, these practices appear to be unconstitutional “involuntary servitude,” yet are widely accepted. The fact that they are apparent exceptions to the rule cannot be justified or explained away using the reasoning Koppelman supplies. It seems that, if (if!) Koppelman is correct about what the Thirteenth Amendment means, then the draft, the trinoda, and jury duty are all unconstitutional, and the Supreme Court has repeatedly gotten it wrong.

Compulsory Service to Private Individuals

The difficulties don’t end there, though. Many people, in many contexts, must render “compulsory service to another private individual” (emphasis mine).

If a man falls overboard, courts have held that a ship captain has a responsibility to stop the ship and attempt rescue, even if the rescue operations and resulting delay will incur enormous (perhaps crippling) expenses:

No matter what delay in the voyage may be occasioned, or what expense to the owners may be incurred, nothing will excuse the commander for any omission to take these steps to save the person overboard, provided they can be taken with a due regard to the safety of the ship and others remaining on board. (United States v. Knowles, N.D. Cal., 1864)

If the captain fails to do so, he can not only be sued civilly by the drowned man’s family, but will be guilty of criminal manslaughter.20

If a railroad crossing guard decides mid-shift to resign his position and abandons his post (or does something tantamount to resignation, like falling asleep at his post), and someone dies on the now-unguarded rail crossing, he, too, will be guilty of manslaughter.

If someone accepts a duty of care for an unrelated elderly man (whether employed to do so or not), but then fails to care for that man every day, day in and day out, and the old man dies of neglect… yep, also manslaughter.

If a landlord promises an apartment water and heat, but then doesn’t do it, he can’t just pay the tenant damages; he has to actually perform the “compulsory service” on the tenant’s behalf. If he doesn’t? He can face criminal charges.

Koppelman’s definition of involuntary servitude is so sweeping that it includes all of these as instances of “involuntary servitude.” Indeed, Koppelman holds that initial consent to a service, or even a signed contract, doesn't matter. Any service becomes unconstitutional involuntary servitude, unless the service provider is able to quit “at any time” and “no law or force compels performance or a continuance of the service.”21 This point is important for Koppelman's abortion argument. Because, in his view, any service provider can change his mind at any time, a woman who consented to sex and/or to pregnancy can change her mind later. The moment she no longer wishes to perform voluntary service for her fetus, according to Koppelman, her pregnancy becomes involuntary servitude and she has a constitutional right to end it as quickly as possible.

Koppelman has to commit to this position, because, if he doesn’t, the Thirteenth Amendment argument for abortion rights really only applies to women who conceive children as the result of rape.22 That would not be a very useful argument for abortion-rights supporters, since only a tiny fraction of abortions are a result of rape! This commitment puts Koppelman in the position of claiming that railroad crossing guards who have to wait until end-of-shift to quit their jobs are victims of involuntary servitude during the remainder of that shift—and then he has to further explain why the courts haven't considered the Thirteenth Amendment applicable in such cases.

Koppelman attempts to explain these apparent exceptions to his rule in three ways. First, he contends that some of these duties are de minimis—that is, so trivial no reasonable person could complain about them. This does not fit very well with current federal circuit court precedent, which holds that, to violate the Thirteenth Amendment, “the temporal duration of the involuntary servitude need not be long; it can be slight.” Nor are these duties necessarily de minimis. Making someone remain at the scene of an accident is de minimis, sure. Making a lifeguard jump into the ocean to save a drowning man? Arguably. (Depends on the circumstances.) However, making someone provide daily care for an elderly man until he dies does not seem de minimis. Nor does cutting deeply into a sea voyage’s profits to conduct all-day rescue operations.

Second, Koppelman argues that all of these duties are terminable. A railroad crossing guard can end his employment through regular channels. A ship captain can quit once he’s back in port, or even stand down and transfer command to his executive officer. An elderly man under your care can be transferred to another guardian, or back into the care of the State. A landlord’s property can be sold. And, heck, if you don’t want to ever have to remain at the scene of a car accident, you can sell your car and stop driving. “In contrast,” Koppelman says (FL ‘90, p493), “unless abortion is permitted, one is not free at any time to abandon the status of being pregnant.”

I don’t think that contrast is as clear he makes it out to be. A landlord who wishes to be free of his duty to provide water and heat can certainly go ahead and sell. All he has to do is evaluate which offers he can entertain (based on leases, city zoning code, etc.), talk with a lawyer, recruit potential buyers, succeed in negotiations with one of them, sign a purchase agreement with a willing buyer, manage the transition for tenants according to the terms of their leases (and more, if he’s a decent person), wait for the buyer to secure financing (this ain’t a single-family home transaction here, where the buyer’s already walking around with a pre-approved mortgage), hire a title clearance company, clear the title, transfer the title, and receive payment. If a landlord decides with absolute certainty that he is getting out of the landlording business as quickly as possible, and he makes this decision on the same day that his wife conceives a child in her womb, it is distinctly possible that the child will be born before he manages to transfer his property. The project will very possibly cost him thousands, if not tens of thousands, of dollars. If he cannot find a willing buyer capable of assuming his own legal responsibilities (no guarantee!), the project may fail altogether. If he doesn’t have the cash flow to pony up thousands or tens of thousands of dollars, he can’t even get started.

Throughout that time period, the landlord may be criminally liable for providing water and heat to all his tenants.

It is true that land ownership is, ultimately, terminable. But, contra Koppelman, so is pregnancy: wait nine months.23

Finally, Koppelman argues that the Thirteenth Amendment forbids involuntary servitude, but does not forbid monetary damages for refusing to perform a service. In other words, if you make a contract and break the contract, Koppelman thinks the State can force you to pay monetary damages of some kind, because this leaves “the individual free to acquire the money in whatever way he prefers, [and] is a lesser deprivation of liberty than the obligation to perform specific work for a specific individual.” On the other hand, for Koppelman, it would violate the Thirteenth Amendment if the courts require you to perform the contract involuntarily, under the coercive threat of criminal penalty. (This is a common piece of received wisdom, though not universally held.) I don’t object to this distinction; monetary and criminal liability are indeed different.24 But all the cases I mentioned above are criminal liability cases, so his defense simply doesn’t pertain here. (Koppelman deploys this argument mainly to defend child support orders and anti-discrimination laws in public accommodations.)

In short, Koppelman’s explanation for these “duty of care” laws is not persuasive. So, once again, we find that, if Koppelman’s definition of “involuntary servitude” in Argument A2 is correct, then “duty of care” laws are at least largely unconstitutional, and the courts have repeatedly gotten it wrong.

Duties of Parent and Child

Only now do we come to the largest difficulty with Koppelman’s broad definition of “involuntary servitude.” If the Thirteenth Amendment says, as Koppelman contends, that no person can ever be compelled to serve another person involuntarily (and can even abandon service after agreeing to provide it!), then what’s the deal with parents and children?

Children are obligated to serve their parents. A couple weeks ago, my four-year-old received her first regular household chore assignment: she has to wipe off the dining room table every night after dinner. She hates this chore and protests every time she is ordered to do it. She is not compensated for her labor (allowance doesn’t start until Age 7) and she wouldn’t want to do the job even if I paid handsomely (she doesn’t understand money and mostly thinks dollars are pretty). According to Koppelman, this is involuntary servitude; not only am I violating the U.S. Constitution every time I do it, but Congress can bypass federalism and take whatever direct action it deems necessary to ensure that I never make my daughter wipe the table again. Also, every other father who makes his child do a chore violates the Constitution. I understand Andrew Koppelman has several children; has he violated the Constitution by coercing his kids to, say, make their beds?

There is no support in American culture or law for the notion that this is unconstitutional. As James Gray Pope wrote a few years ago, “Parents enjoy plenary authority over their minor children… [N]obody would contend that children generally suffer a condition of slavery prohibited by the Thirteenth Amendment.”25 There's not a lot of case law confirming that plenary parental authority is permitted by the Thirteenth Amendment, because (to quote Koppelman on a different point), the principle is so embedded in the bedrock of our law that "no litigant has challenged it in many years. The case... is strengthened, not weakened, by relying on a principle so fundamental that it is never questioned."

Yet if Koppelman's understanding of "involuntary servitude" is correct, we are all wrong, and children generally do suffer a condition of slavery! The labor I demand of my kids is, I think, de minimis (although my children would argue this strenuously), but many parents demand more of their kids, like farmers who require their kids to help out around the farm. Everyone agrees that parents demanding more than de minimis labor from your kids is just fine.

Meanwhile, my kids have no power to leave my service, except in truly exceptional circumstances. Their status and duties are not terminable. They cannot even abandon work I have assigned them and pay monetary damages instead; they will instead face domestic criminal penalties (five-minute time outs, deprivation of desserts, no Star Wars, et cetera.) (My four-year-old believes all these punishments violate her Eighth Amendment rights, but that’s another blog post.)

Parents, meanwhile, have a legal obligation to provide for their children. Period. If you are a custodial parent, and you don’t take minimally decent care of your kids, you’re going to jail, and, frankly, you deserve it. We are bound by law to the compulsory service of our children. This duty is binding even if we hate it, even if we’re very poor, even if we’re forced to sacrifice every comfort we have in the world to fulfill our duty. We are bound by law to serve our children even if it puts our physical and mental health at elevated risk. (Arguably, it routinely does just that!)

This is exactly the same burden laid upon pregnant parents in a polity where abortion is prohibited: parents are bound by law to take minimally decent care of their kids, even if they hate it, even if they’re poor, even it risks some injury26 to our physical and mental health. Koppelman attempts to resist this, one last time, by arguing that parents who decide they don’t want to be parents anymore can terminate their parenthood by giving the kids up for adoption. However, what if there is no opportunity for adoption? (Perhaps your child is profoundly disabled and nobody wants to adopt him. Perhaps you are living in a time of lesser prosperity and/or greater fertility, such that national demand for adoptable children has been satisfied.) Koppelman's argument implies that, if you can't adopt your child out, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees you the inalienable right to leave your child alone in the woods to die of exposure.

Perhaps this isn’t surprising, since Koppelman also believes that the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees you the inalienable right to not just allow your child to die in the woods, but to violently dismember her in utero. But I hazard that most U.S. courtrooms would regard a “constitutional right to expose infants” with considerable skepticism.

Once again, we must ask whether Koppelman’s definition of “involuntary servitude” is wrong. (If he’s right, then everybody else is wrong.)

Koppelman himself, to his credit, reconsiders the question of parental obligations in Forced Labor Revisited ‘10, recognizing his position as a weakness of his original piece. But his reconsideration makes no headway. He merely expresses ambivalence, then concludes by actually digging himself a little deeper into the hole:

I am sure, however, that the… claim… that parental obligations never raise a Thirteenth Amendment issue, is false.

I am not familiar with any authority to support Koppelman’s position here.

At this point in Forced Labor Revisited ‘10, Koppelman falls back to Argument B, seeming to abandon Argument A to the parental obligation critique.

I, however, am not quite ready to be done with Argument A. Professor Koppelman’s explanation of the Thirteenth Amendment is not looking so good at this point, but that raises the question: what does the Thirteenth Amendment mean? Let’s take a few minutes to build the Thirteenth Amendment back up on new and stronger foundations.

Servitude in the Early United States

When you put two words together into a phrase, the result is usually a phrase that means the sum of the two words. For example, the phrase “color television” means television wave transmitted with color data (or a television set capable of receiving those transmissions). People often think the same way about “involuntary servitude”: surely, it must mean any situation where a person serves without a choice.

Yet there are other phrases where putting two general words together means something quite different from what the words mean on their own. For example, the phrase “real property” feels like it should mean any property you own that is really your property, not imagined or borrowed or conditional—a chair, for example, or this keyboard I’m typing on. But that would be wrong: “real property” means land. A chair is never real property. (It might be “personal property.”)

“Involuntary servitude” was the second kind of phrase. It referred to a specific kind of labor contract. Because this kind of labor contract no longer exists, it is easy to misunderstand what involuntary servitude entailed, and how the institution related to slavery.27

In the American British Colonies, and in the very early United States, there was a broad legal concept called “servitude.” You probably learned about “indentured servitude” in fifth-grade social studies. The idea of indentured servitude was that you could “enter service” with someone for a set number of years.

Sometimes this was done as an apprenticeship: you serve a blacksmith (or whatever) for seven years and then you have the skills to open your own blacksmith shop. Sometimes it was done to get to America: you’re a poor Londoner who can’t afford passage on a boat, but there’s a rich family that will pay for your boat ride if you serve them for two years, so you agree. Sometimes you’re a Downton Abbey character who has been bound and re-bound to a family “in service” (annually, suggests Blackstone), not just for your whole life, but for generations previous. The point is, this was a not-uncommon legal arrangement between a master and a servant, and it was facilitated by a big ol’ mess o’ laws.

If you were an indentured servant, you could not quit while your indenture lasted. If a person “bound to service” refused his master’s (legal) orders (or, worse, ran away), a typical punishment (p451) was to add one year to your indenture. It is understandable why indentured servants might want to run away: they tended to be worked very hard, because, until the indenture expired, they were slave labor! They had to work whatever hours they were instructed to work, on whatever task assigned, living on whatever provisions their masters made for them, without hope of compensation (except for the promise of eventual freedom and freedom dues). Indentured servants retained their rights to life and property, but they were understood by law to have temporarily forfeited their liberty.

Most indentured servitude was voluntary servitude. A servant and master would sign a labor contract spelling out all the terms of service (how long, what the servant would receive in exchange, et cetera), each acting (at least in theory) with full and informed consent. This contract could be sold between masters. Once the contract was signed, the servant was bound for the term of the agreement, even if he later changed his mind—but he had entered into the agreement voluntarily, so this was still considered voluntary servitude even after the servant changed his mind.

There were also cases of involuntary servitude. In these situations, the State would force individuals into servitude. Here are some examples of how a free citizen could be forced to work for years in slave-like conditions without compensation:

A court could sell you into involuntary servitude in payment of debt (p103).

Vagrants, vagabonds, and people found wandering who couldn’t give “satisfactory accounts of themselves” were sometimes assumed to be runaway servants, imprisoned, and then sold into servitude in order to pay the prison fees (p107), which, if you’re into evildoing, is a pretty neat trick.

In colonial Virginia, mixed-race children were automatically bound to involuntary servitude until age thirty-one.28 A similar rule held in North Carolina (p83-84).

The children of poor people (or orphans) could be “set to work” in involuntary service, which could last until adulthood. On at least one occasion (p49), this involved kidnapping orphan children of London off the street and transporting them to Jamestown, where they were indentured out as “apprentices” until age 24.

A court could order involuntary servitude in lieu of civil or criminal fines. A Pennsylvania law of 1701 fined housebreakers and arsonists four times the amount stolen or damage inflicted (rather a lot of money), and, if they couldn’t come up with the money, sale into involuntary servitude was mandatory (p102). A colonial North Carolina law fined people for harboring runaway servants, and, if they couldn’t pay, sold them into involuntary servitude to raise the money (p34).

As we see from the above, criminals might be forced into involuntary servitude; this could include transportation from England into American involuntary servitude (p113). This was not the same as prison labor, where criminals do service for the State. In the colonial and early American periods, the State could actually hand criminals over to private citizens, who would keep them as involuntary indentured servants for a number of years for their own private benefit.

You may be thinking that there wasn’t very much difference between “involuntary servitude” and “slavery.” You’re not wrong! As one dissertation (p5) put it, “the legal distinction between White servitude and Black slavery did not occur for more than forty years after the system’s invention.” Pennsylvania’s 1780 law of gradual emancipation used “servitude for life” as a synonym for slavery. The U.S. Constitution’s infamous fugitive slave clause (requiring states to return runaway slaves from other states) applied with equal force against indentured servants.

However, as the institutions developed, there did come to be important distinctions between involuntary servitude and what Blackstone called “absolute slavery.” Abolitionists worked hard (p147-148; free draft available) to drive those critical distinctions home to the public in the face of an increasingly tyrannical29 Slave Power:

Involuntary servitude typically lasted seven years or less. Slavery was for life.

An involuntary servant lost his right to liberty, but retained his rights to life and (to a limited extent) property. A slave had no rights before the law whatsoever. In practical effect, and sometimes by its plain text (p91), the law allowed masters to murder slaves with impunity.

An involuntary servant was a civil person, with the ability to petition for redress in court if his master violated his rights. A slave was a species of livestock, not a civil person. Even where laws existed that (very theoretically) forbade masters from abusing their slaves, slaves themselves could not sue or testify in court against their masters, even if they were victims of such abuse.

An involuntary servant was only bound to labor of some sort. A slave, as a chattel or livestock, could be used in any way whatever. Often, the rape of a slave was not a crime (p66-69).

The children of slaves were also slaves, a deeply bizarre legal rule that everyone knew full well even at the time was nuts.

From this, we see that servitude (whether voluntary or involuntary) shared many features with slavery.30 Like slavery, servitude (as it evolved in British America) described a “private economical relation,” a legal bondage, of a servant to a master. The bound servant had no right to resist the commands of his master, and many of his other rights (such as the right to marry) were restricted (for a slave, all rights were extinguished). The master was a private citizen unrelated to the servant.

Compulsory service to the State (via conscription or the trinoda) might be considered good or bad, but it was not considered involuntary servitude. Likewise, domestic relationships—the compulsory service of children to parents, parents to children, or wives to husbands—might be considered good or bad, but were not considered involuntary servitude (pp155-160).

On the other hand, debt peonage, of the sort dealt with by the Supreme Court in Bailey v. Alabama, would constitute at least voluntary servitude, and might constitute involuntary servitude if the design of the program were sufficiently biased against the servitor (as it certainly was in Alabama’s case).

The Careful Language of Amendment XIII

To the best of my understanding, the institutions I have just described were what the American People understood themselves to be abolishing when they first decided to outlaw “slavery and involuntary servitude.” That occurred, not in 1865, but in 1787, when Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance. This ordinance governed the territory spanning from modern-day Ohio to modern-day Minnesota, and it provided:

There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.

The precise meaning of this provision was tried and tested over the following seventy years. It was incorporated into over a dozen state constitutions, the Missouri Compromise, and other provisions, until 1857, when (following a Roe-like legal theory) the Supreme Court struck down the Missouri Compromise in Dred Scott v. Sandford.31

During those seven decades, both voluntary and involuntary servitude effectively died out within the United States. The Revolutionary War had already severely disrupted the flow of indentured servants from abroad, Parliament banned exportation of servants soon after (p254), the cost of trans-Atlantic passage steeply declined, and regulations increased (p263), all of which put great strain on the system. “Debtors’ prisons” slowly disappeared, and with them their supply of involuntary servants. Robert Steinfield says (p29-30):

Until 1820… Americans continued to import large numbers of indentured servants and contract laborers whenever the international situation permitted it. But in 1820 the market in imported servants collapsed. Thereafter, between 1820 and 1830, relatively few adult white servants were imported, and after the early 1830s, none were… [A]dult white European servitude simply disappeared.

The North moved toward free labor, under which everyone worked for wages. The South moved toward slavery, which (from the master’s perspective) had all the advantages of ordinary servitude but with way fewer strings attached, and which (thanks to the law of hereditary slavery) didn’t require importation or recruitment to be permanent.

As this happened, the public meaning of the words “involuntary servitude” broadened somewhat. Without the original institution of involuntary servitude to compare it to, judges became more inclined to identify the language barring “involuntary servitude” with the institution formerly known as "voluntary servitude." That is, courts began to rule that a man who willingly sold himself into servitude (traditionally considered "voluntary servitude") might change his mind and walk away before the service was ended. If his master detained him further, it could, under certain circumstances, become "involuntary servitude."

During this transition, the circumstances that turned lawful service into unlawful “involuntary servitude” varied by state, as described by Professor Nathan Oman in his invaluable Specific Performance and the Thirteenth Amendment,32 but broadly comprised four judicial tests:

Did the servant enter the indenture in “a state of perfect freedom”?

Did the indenture provide proportionate compensation or consideration?

How long did the indenture last? Longer indenture meant greater court suspicion, especially given the traditional rules that indentures had to end before five or seven years.

Did the master “dominate” the servant, especially by asserting a right to physically harm or detain the servant outside legal channels? If so, that made courts very suspicious indeed.

This expanded interpretation of the original law does not seem to have been understood by the judges involved to be an expansion; they were trying to follow the text as they understood it. Some traditionally voluntary servitude was now at risk of being declared “involuntary” and voided… but, since the practice had already mostly died out in the meantime, this caused no great waves.

This growth in the meaning of “involuntary servitude” encompassed only contracts between masters and servants for labor. No source that I have consulted (including Koppelman) presents any evidence that the meaning of “involuntary servitude” went any further than this in 1865.

As Professor Kurt Lash details in his helpful working paper, Roe and the Original Meaning of the Thirteenth Amendment, the drafters of the Thirteenth Amendment consciously chose to rely on the tried-and-tested language of the Northwest Ordinance, rather than come up with new language freeing the slaves. They deliberately used precisely the same language as Congress had in 1787, intending to enact precisely the same rule of law as Congress had in 1787.

In my opinion, their understanding of the language had unconsciously drifted far enough from what Congress meant in 1787 that the same words probably meant something slightly different, but the involuntary servitude they abolished was still strictly that of indenture by servants to unrelated private masters for defined, extended periods.

Since the military draft, jury duty, compulsory road-building, public-accommodations laws, good samaritan laws, duty-of-care laws, landlord regulations, parental rights, child neglect laws, household chores, and anti-abortion laws do not pertain to indenture by servants to unrelated private masters, and do not establish anything that looks remotely like that relationship, they are not “involuntary servitude.”

Since debt peonage, the coolie system, and specific performance requirements in contracts can (at some times, under some circumstances) create conditions that involve or closely resemble the private indentures outlawed by the Northwest Ordinance and the Thirteenth Amendment, they might be voided by courts or restricted by Congress as involuntary servitude33 —but not always! For example, in Robertson v. Baldwin (1897), the Supreme Court compelled seamen to fulfill their contracts against their will, ruling that they had entered the contracts voluntarily, so their service was voluntary.34

This division comports nicely with our subsequent case law defining involuntary servitude, and requires none of the hoop-jumping and acrobatic flexibility displayed by Koppelman’s search to justify the Thirteenth Amendment’s “exceptions.” No justification is required, because the draft, landlord regulations, anti-abortion laws, and so on are not exceptions. They never fell within the Thirteenth Amendment’s scope in the first place, and can only be read into the Amendment by misunderstanding the Amendment’s historical meaning. Koppelman’s Argument A2 is not precisely false, but it is fatally incomplete in a way that causes Argument A4, A5, and A6 to fail in turn.

The reality is that human beings are not characters in an Ayn Rand book. We all have unchosen obligations, and we always will. The State has always enforced at least some of the most important unchosen obligations. I hope it always will, because the alternative—absolutist libertarianism—would be a hellscape. It is not servitude to be forced: to render aid to a man overboard; to rent a Black man a room at your hotel; to make a cake for a gay wedding;35 to not kill a child by abortion or exposure. To make out that these are “servitude” requires a definition of “servitude” that did not exist when the Thirteenth Amendment was written.36 (Even less could any of these be called “slavery” within the meaning of the Thirteenth Amendment.) Nor could you justify calling it “servitude” based on a fair reading of subsequent case law.

Oh, snap, I haven’t really talked about the case law yet, have I?

I now turn to Koppelman’s Argument B, which is a sophisticated, lawyerly argument based largely on the interpretation of specific acts of the 39th Congress, plus a body of Supreme Court case law that you, the average citizen, have never heard of, and which you have no reason to know (unless Koppelman’s Argument B is correct) (but it isn’t). If you were only here because someone shouted “unwanted pregnancy is involuntary servitude!” at you in a Reddit comment thread, you can be done at this point. This Blog Post has disposed of the obvious and, from here on out, will be delving into the esoteric.

Was the Civil Rights Act of 1866 Constitutional?

There is an argument that the Thirteenth Amendment bans more than just slavery and involuntary servitude themselves. According to this argument, the amendment also bans the “badges and incidents” of slavery—or at least allows Congress to ban those “badges and incidents,” at Congress’s discretion. Since this notion is core to Koppelman’s Argument B, let’s explore it (without committing to it).

The most important evidence for the “badges and incidents” theory is that, two seconds after passing the Thirteenth Amendment, most of the people responsible for passing it shook off their laurels and passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which did a lot more than simply ban slavery (emphasis mine):

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States; and such citizens, of every race and color, without regard to any previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall have the same right, in every State and Territory in the United States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties, and to none other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, to the contrary notwithstanding.37

Some, like Senator (and future Vice President) Thomas Hendricks (D-IN), objected: the Thirteenth Amendment banned slavery and involuntary servitude, but did not say anything about contracts, property, or other civil and constitutional rights.

Sen. Lyman Trumbull (R-IL), the guy who had introduced the Thirteenth Amendment, confidently proclaimed that, yes, this bill was authorized by his Amendment, and urged Congress in stirring language:

If the construction put by the Senator [Hendricks] from Indiana upon the amendment be the true one, and we have merely taken from the master the power to control the slave and left him at the mercy of the state to be deprived of his civil rights, the trumpet of freedom that we have been blowing throughout the land has given an uncertain sound, and the promised freedom is a delusion. Such was not the intention of Congress, which proposed the Amendment itself. With the destruction of slavery necessarily follows the destruction of the incidents of slavery. When slavery was abolished slave codes in its support were abolished also.

Those laws that prevented the colored man going from home, that did not allow him to buy or to sell, or to make contracts; that did not allow him to own property; that did not allow him to enforce rights; that did not allow him to be educated, were all badges of servitude made in the interest of slavery and as a part of slavery. They never would have been thought of or enacted anywhere but for slavery, and when slavery falls they fall also.

…If in order to prevent slavery Congress deem it necessary to declare null and void all laws with will not permit the colored man to contract, which will not permit him to testify, which will not permit him to buy and sell, and to go where he pleases, it has the power to do so, and not only the power, but it becomes its duty to do so.

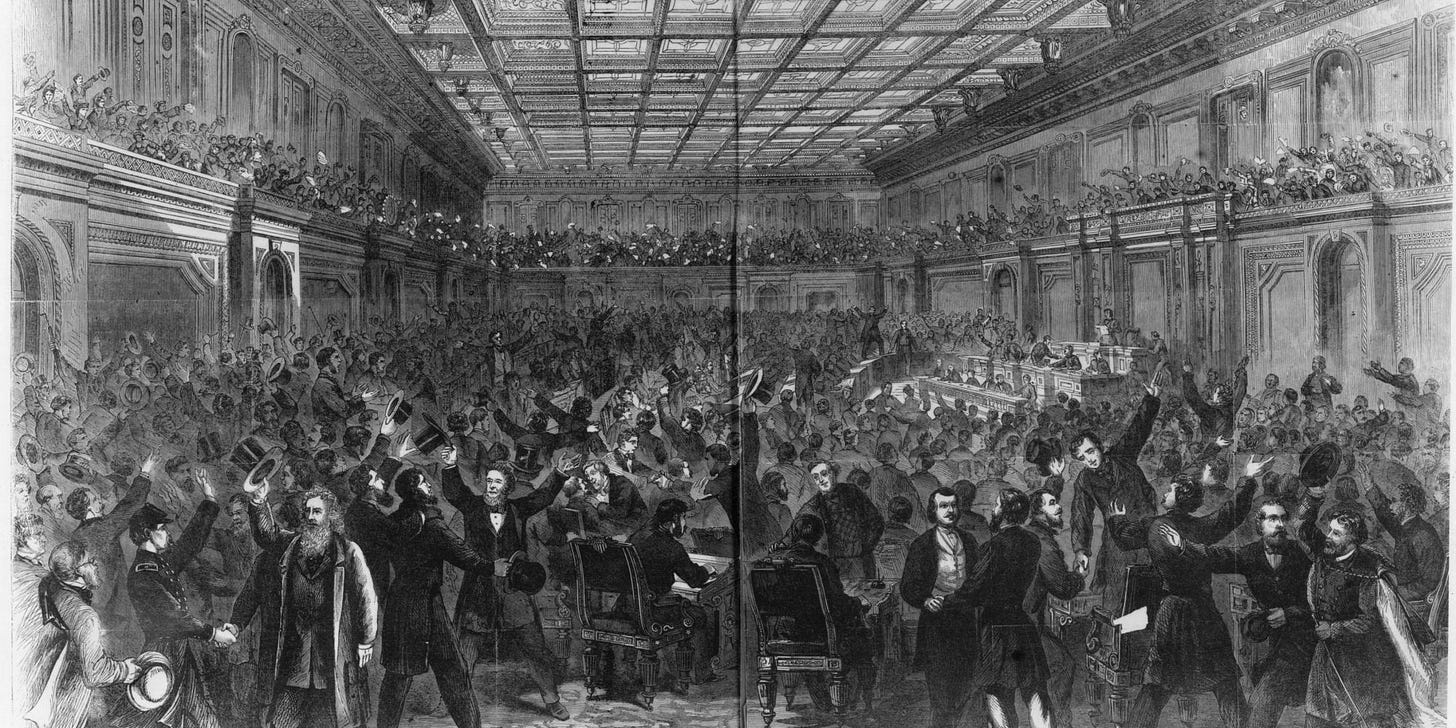

As though to emphasize the force with which the Thirteenth Amendment Congress agreed with Trumbull, they passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 as he requested… then passed it again, over President A. Johnson’s veto, by a two-thirds majority in both houses. This was the first time in American history that major legislation was passed over a presidential veto.38

On the other hand, Kurt Lash and David Upham each offer good reasons to believe that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 could not, in fact, be justified under the Thirteenth Amendment, despite Trumbull’s bluster and Congress’s acquiescence. (Jennifer Mason McAward reports similar evidence but draws more equivocal conclusions from it.)

Rep. John Bingham (R-OH), who was largely responsible for the Fourteenth Amendment and strongly supported the goals of the Civil Rights Act, nevertheless voted against it, arguing along the same lines as Hendricks:

[I]n view of the text of the Constitution of my country, in view of all its past interpretations, in view of the manifest and declared intent of the men who framed it, the enforcement of the bill of rights, touching the life, liberty, and property of every citizen of the Republic within every organized State of the Union, is of the reserved powers of the States, to be enforced by State tribunals and by State officials acting under solemn obligations of an oath imposed upon them by the Constitution of the United States. Who can doubt this conclusion who considers the words of the Constitution: ‘The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the State respectively, or to the people?’ The Constitution does not delegate to the United States the power to punish offenses against the life, liberty, or property of the citizen in the States, but leaves it as the reserved power of the States, to be by them exercised. . . . I am with [Mr. Wilson] in an earnest desire to have the bill of rights in your Constitution enforced everywhere. But I ask that it be enforced in accordance with the Constitution of my country. (Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Sess. 1291, 9 March 1866.)

Bingham’s objections pushed Congress away from justifying the Civil Rights Act as an exercise of its Thirteenth Amendment power. Congress instead tried to justify it under (variously) the Fifth Amendment’s due process clause, the Republican Form of Government Clause, the Comity Clause of Article IV, the Necessary & Proper Clause of Article I, the Naturalization Clause, Congressional war powers, implied powers under hated pro-slavery decisions like Prigg v. Pennsylvania, and/or outright rejection of Barron v. Baltimore (1848) (which had decided that the antebellum Bill of Rights did not apply against the states). Bingham and his allies thought none of these alternatives fit the bill, either, and insisted that the Civil Rights Act would not be constitutional unless the Constitution was amended (again). The entire debate is painstakingly reconstructed in Kurt Lash’s Enforcing the Rights of Due Process: The Original Relationship Between the Fourteenth Amendment and the 1866 Civil Rights Act.

Although, in the short term, Congress overrode Bingham’s concerns (variously citing all of the above constitutional clauses, not only the Thirteenth Amendment), Bingham’s interpretation was certainly a live view among the contemporary public. As Lash details in Roe and the Original Meaning of the Thirteenth Amendment, President Andrew Johnson’s administration—including the famous anti-slavery radical, Secretary of State William Seward—not only adopted Bingham’s limited understanding of the Thirteenth Amendment, but even convinced dubious slave states that it only did what it said: abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, no funny business.

The slave states, for their part, were largely unrepresented in Congress at this time, due (mainly) to their grave violations of the Republican Form of Government clause (see America’s Constitution, pp364-380). Nonetheless, they were still part of the public (albeit a largely treasonous one), and they seem to have more or less taken Bingham’s view of the amendment, with several of them adopting resolutions to that effect (p33). Moreover, it strains credulity that the slave states would have so easily adopted the Thirteenth Amendment if they shared Trumbull’s broad understanding of its text, rather than Bingham’s narrow one, especially since said slave states were busy passing Black Codes at this very moment in history. (The slave states really dug in their heels against the Fourteenth Amendment, which they—correctly—recognized as a grave threat to their entire system of apartheid.)

Congress certainly gave the appearance of buckling to Bingham’s concerns when, less than three months after passing the Civil Rights Act, they also passed Bingham’s Fourteenth Amendment. The Fourteenth Amendment contains several passages that strongly parallel the Civil Rights Act, including its declaration of citizenship and its due-process/equal-protection clauses. Bingham expressly intended the Fourteenth Amendment to enable a bill like the Civil Rights Act, and the Civil Rights Act was actually re-passed (with modest alterations) in 1870, once the Fourteenth Amendment had been ratified.

Professor Koppelman is, not unreasonably, a mite suspicious of modern-day scholars who claim to understand the original public meaning of the Thirteenth Amendment better than Lyman Trumbull. I look forward to reading Koppelman’s further development of the scholarship surrounding the Thirteenth Amendment’s original meaning, which could certainly benefit from his contributions. For the time being, however, it seems to me that the weight of evidence suggests that either:

[A]: The 39th Congress lacked the power to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (until the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified and cured the lack);

[B]: The 39th Congress had the power to pass the Civil Rights Act, not based on the Thirteenth Amendment, but on one of the other provisions Congress mentioned in the debates; or perhaps even

[C]: The 39th Congress had the power to pass the Civil Rights Act because the Thirteenth Amendment implicitly provided Congress with powers identical to those given explicitly by the Fourteenth Amendment—which means the Thirteenth Amendment provides no power beyond what the Fourteenth Amendment grants and is therefore useless as an alternative source for abortion rights.

However, as I said, for the sake of exploration, we are going to accept (and put the best possible light on) Koppelman’s theory:

[D]: The 39th Congress had the power to pass the Civil Rights Act because the Thirteenth Amendment provided Congress with the power (distinct from the powers granted by the Fourteenth Amendment) to abolish not only slavery and involuntary servitude themselves, but also to erase certain other “incidents” of slavery which gave “the trumpet of freedom… an uncertain sound.”

This theory is not only the basis of Koppelman’s Argument B1. It finds considerable support in various U.S. Supreme Court cases, and it appears to have been the view of a large portion of the 39th Congress itself, including Lyman Trumbull.

Rolling With It

Even a skeptic must admit that Trumbull’s thinking isn’t exactly bats, either. The central fact of slavery, the thing that distinguished it from ordinary servitude, was the fact that it rendered its victims civilly dead. It un-personed them. A servant (whether voluntary or involuntary) was still a person, still had rights, could still own property, and could still seek redress in court. A slave, in the eyes of the law, was a cow. Less than a cow, really; raping a cow would at least get a plantation owner executed for bestiality, but raping a (female) slave was (often) not even a crime.

Since the decisive element of slavery was that it extinguished civil personhood, it’s not outrageous to think that the abolition of slavery directly entailed civil personhood, and thus all the ordinary privileges and immunities that accrued to ordinary citizens. As Judge William Gaston wrote in State v. Manuel, a celebrated 1838 North Carolina Supreme Court decision that stayed influential (p8) through the turn of the century:

According to the laws of this State, all human beings within it who are not slaves, fall within one of two classes. Whatever distinctions may have existed in the Roman law between citizens and free inhabitants, they are unknown to our institutions. Before our Revolution all free persons born within the dominions of the king of Great Britain, whatever their color or complexion, were native born British subjects—those born out of his allegiance were aliens. Slavery did not exist in England, but it did exist in the British colonies. Slaves were not in legal parlance persons, but property. The moment the incapacity… of slavery was removed[,] they became persons, and were then either British subjects or not British subjects, accordingly as they were or were not born within the allegiance of the British king. Upon the Revolution, no other change took place in the law of North Carolina… Foreigners until made members of the State continued aliens. Slaves manumitted here became free-men—and therefore if born within North Carolina are citizens of North Carolina.

For many in the Congress that abolished slavery, to be free from slavery was to become a citizen; there was no middle ground (p442). Thus, an amendment banning slavery by that fact guaranteed citizenship, with all the attached privileges and immunities.39 And, as Chief Justice John Marshall put it in upholding the First Bank of the United States:

We admit, as all must admit, that the powers of the government are limited, and that its limits are not to be transcended. But… [l]et the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all the means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to the end, which are not prohibited, but consistent with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional.

I don’t want to abuse this quote (as it has sometimes been abused), but is not the restoration of rights extinguished by slavery fairly within the scope of an amendment abolishing slavery? Wouldn’t that include the civil rights "to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property"? After all, in the American system, what use is any right—including the right not to be enslaved—if you don't possess the fundamental civil right to vindicate your other rights in court?

So the argument went. I am not entirely convinced, but it is reasonable on its face, it’s put down roots in our law, and this understanding seems to have been shared by enough of the public to raise questions for any originalist who disagrees with it. Koppelman’s “egalitarian” argument depends on it. We are therefore rolling with it.

Badges, Vestiges, and Incidents

The collection of rights and privileges that had been suppressed by (or because of) slavery came to be known as the “badges and incidents” of slavery (in part thanks to Trumbull’s influential speech, which used that language). Koppelman explains in Originalism, Abortion, and the Thirteenth Amendment (p1932):

Badges, incidents, vestiges, relics: the Amendment reaches all of these because they are associated in some way with slavery. …Property is familiarly regarded as a bundle of rights. Slavery is a bundle of disabilities. Each one of those disabilities is part of slavery and so raises Thirteenth Amendment concerns.

Debate about the exact contents of this “bundle of disabilities” began, in earnest, with the debates over the Civil Rights Act. I will now briefly trace the history of that debate in subsequent decades, omitting many related issues40 along the way.

In United States v. Rhodes (1866), Justice Swayne (riding circuit on his own) ruled in favor of the Civil Rights Act of 1866—even though the Fourteenth Amendment had not yet been ratified. Opponents argued that both Black slaves and free Blacks were frequently deprived of their civil rights, and so depriving Black people of civil rights was not truly an incident of “slavery.”41 Justice Swayne was unpersuaded: “[Free Blacks] had but few civil and no political rights in the slave states. Many of the badges of the bondsman’s degradation were fastened upon them…. [Emancipation] was doubtless intended to reach further in its effects as to everyone within its scope.”

Blyew v. United States (1871) was a defeat for civil rights. However, the dissent claimed that the Thirteenth Amendment entitled Black people to access the justice system, and the majority didn’t disagree. (The case was lost on other, more technical grounds.)

In the Civil Rights Cases (1883), the full Court agreed that the Thirteenth Amendment allowed Congress to abolish a litany of what it called the “badges and incidents” of slavery: “Compulsory service of the slave for the benefit of the master, restraint of his movements except by the master's will, disability to hold property, to make contracts, to have a standing in court, to be a witness against a white person, and… severer punishments for crimes.” However, in 1875, Congress had also invoked the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish racial discrimination in public accommodations (hotels, taxis, bakeries, and so on). The Court rejected this as a bridge too far, emphasizing that the Thirteenth Amendment protected civil rights, not social rights.42 In the process, the Court also sided with the losers in United States v. Rhodes, ruling that, because free Blacks had not enjoyed rights to public accommodations before the War, public-accommodations discrimination was not a “badge of slavery” for emancipated Blacks after the War.

In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Court refused to strike down a Louisiana law that required trains to be segregated. Plessy was mostly about the Fourteenth Amendment, but the justices also ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment could not apply here, because segregation did not “stamp” anyone with a “badge of inferiority.”

In Hodges v. United States (1906), the full Court finally heard a case directly about Congress’s power under the Thirteenth Amendment to ban the “badges and incidents” of slavery—and, surprisingly, rejected forty years of its own dicta to rule that the Thirteenth Amendment could only be used directly against slavery or involuntary servitude, not to address slavery’s “badges and incidents.” In effect, they held the Civil Rights Act of 1866 unconstitutional insofar as it relied on the Thirteenth Amendment.43