“The Supreme Court has abandoned stare decisis,” is a thing you hear a lot these days. Here’s a reddit comment I came across in July:

Just remember, what’s good for the goose is good for the gander.

Supreme Court justices historically have shown great deference to the decisions of their predecessors, almost never reversing them. If the court’s current conservative majority continues to overturn longstanding precedent simply because they disagree with it, what’s to stop future justices from doing the same? Eventually control of the Court will swing back in the other direction, and those justices could just as easily start reversing the decisions that you support.

Admittedly, you mostly only hear this complaint from people who only believed in stare decisis for one specific case. (This post is not about that case, but it rhymed with “Bro, the spade!”)

Stare decisis is the principle that, under certain circumstances, a court ought to continue to follow its precedents, even when the court has good reason to believe that the precedent was wrongly decided.1 This principle (the argument goes) promotes the important values of stability and predictability in the law, which is worth the not-insignificant price: by adhering to a concededly wrong decision, the rule of stare decisis necessarily requires courts to consciously choose to do an injustice to the one of the litigants in the case. That is, one litigant should win the case (because of the law), but she will lose the case instead (because of stare decisis). This is unjust, but, under certain circumstances, this injustice may be justifiable due to broader considerations.

There’s much more to be said about stare decisis (and I said a teensy bit of it in “The Rest of the Rest of Dobbs”), but that’s not what I’m here to do today. Today, I want to find out how much the Supreme Court of United States has adhered to the principle of stare decisis, historically, and whether the current Supreme Court has been noticeably more reckless about casting aside precedents.

This is a really interesting empirical question! Many people, like the redditor from the start of this article, are under the impression that overturning a prior precedent is very rare, and thus that overturning any particular precedent demands extraordinary justification. Many other people are under the impression that the Supreme Court overturns prior precedents whenever the mood strikes, and thus don’t see stare decisis as much more than a parlor game. But most people believe in stare decisis for decisions they like while opposing it for decisions they dislike.2

What both conservatives and progressives need, then, is a sense of perspective. How often does the Supreme Court overturn its own precedents? Is the modern Court doing it more than usual? If so, how much more? Is Dobbs exceptional, or ordinary?

To help answer this question, I have divided the Court’s history into ten historical periods. These periods are of somewhat different lengths, but I allowed this because each era is distinctively different, with a clear start and end date. The periods are:

The Early Court (1789-1835): Until Chief Justice Marshall’s death.

The Taney Court (1836-1864): Best known for the foul Dred Scott decision, and deservedly so.

The Reconstruction Court (1864-1897): A more active Court that used its authority largely to deliberately misread the Reconstruction Amendments, damaging the law in ways that persist to this day.

The Lochner Era (1897-1937): A period of conservative activist judges. In the Lochner decision, they established a “liberty of contract” that allowed the Court to strike down any economic regulation it disliked, from minimum wages to child labor laws. This was a major guarantee of individual liberty, one that many people (including workers) relied on for forty years (although many others opposed it). If anyone tells you that the Supreme Court never rescinded an individual right before Dobbs, teach him about Lochner.

The Post-Lochner Transition (1937-1953): The Court became rapidly more progressive after Lochner fell, undoing many of its precedents.

The Warren Court (1953-1970): A byword for newly “discovered” constitutional rights, judicial reinventions of old rights, and the overdue reanimation of civil rights.

The Burger Court (1970-1986): I think the Warren and Burger courts should be counted together, but some people have the strange idea that Chief Justice Burger or his Court were conservative, so I must count them separately, or those people will think I’m pulling a fast one.

The Rehnquist Court (1987-2005): Reagan and Bush attempted to shift the Court from the hard left toward the American center. Thomas and Scalia debuted their originalist theories at the Supreme Court during this time, but were mostly stuck writing dissents. Progressives still won most3 cases.

The Kennedy Court (2006-2020): After “swing justice” Sandra Day O’Connor retired and was replaced by Justice Alito, a conservative stalwart, Justice Anthony Kennedy became the swing vote on a tied court. Everyone catered to him, so America was governed by his socially liberal/libertarian views. Both progressives and conservatives won important cases during this time.4 Curiously, after Kennedy retired, Chief Justice John Roberts shifted decisively to the left in order to maintain this “balance of wins” for a couple more years.5

The Barrett Court (2020-present): When conservative Justice Barrett replaced progressive Justice Ginsburg, conservatives gained a durable Supreme Court majority for the first time in more than 80 years.

So, how did each era treat precedents?

For our answer, we can turn to the Library of Congress, which maintains a website that lists every occasion on which the Supreme Court has ever overturned a precedent:

Table of Supreme Court Decisions Overruled by Subsequent Decisions

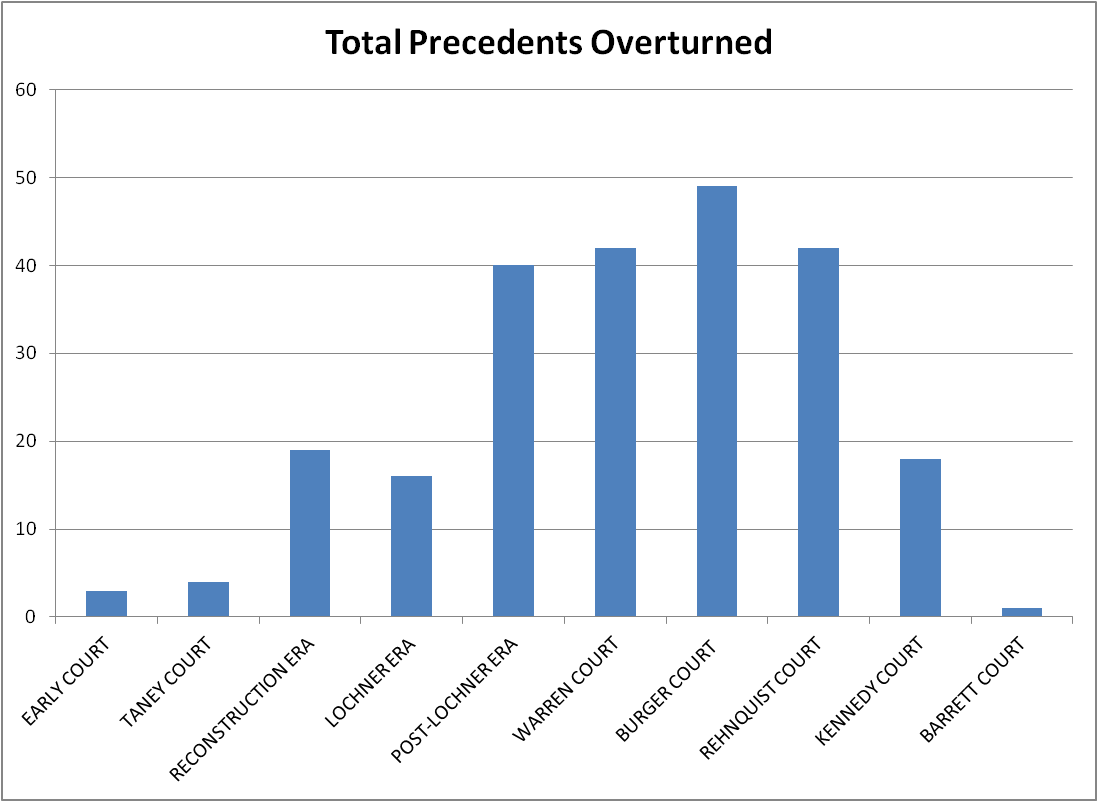

We can use this as our data source.6 After that, it's just a matter of spending enough time with spreadsheets to produce this:

Looks like the more progressive eras overturned more precedents.

“That’s hardly fair. There’s a difference between overturning a one-year-old precedent and a ninety-nine-year-old precedent. The older one is more established in our law, so overturning it is a much bigger deal!”

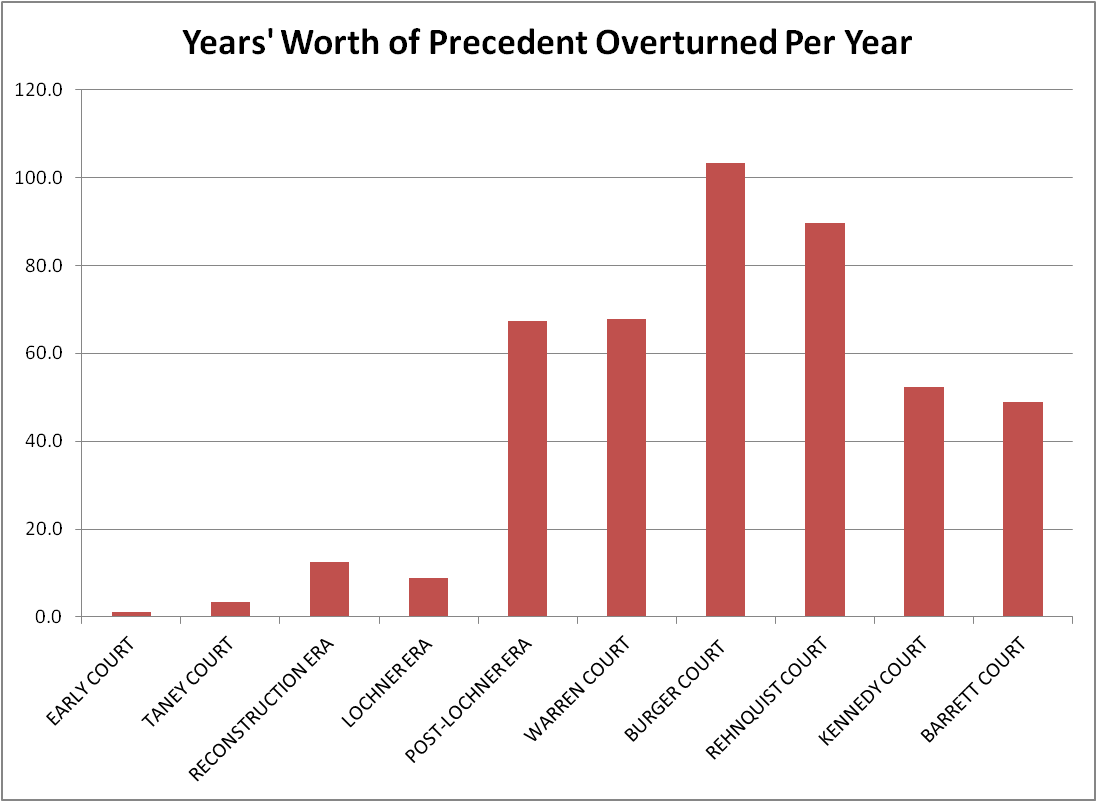

Quite right, guv’nor. Instead, let’s figure out how many precedent-years each era overturned. If a court overturns a two-year-old precedent, that’s 2 precedent-years. If it also overturns a ten-year-old precedent, that’s 10 precedent-years, for a total of 12 precedent-years overturned.

By this slightly smarter measure, who’s torn the most out of the guts of American law and replaced it with something new?

Still looks like the most progressive eras.

“You still aren’t playing fair with us, are you? The Burger Court lasted 20 years! The Barrett Court hasn’t yet turned 2! The other eras had a lot more time to overturn precedents.”

This is quite so. The Barrett Court is really only a year old; the Burger Court was 17 years; the Lochner Era 40 years; the Early Court 46. Summing them up like we did in those charts is therefore not a fair apples-to-apples comparison. Instead, let’s look at how many precedents (and precedent-years) each era overturned in an average year. Which eras overturned precedents the fastest?

It, uh… it still looks like the most progressive eras.

Apparently, prior to the fall of Lochner, the Supreme Court followed stare decisis very strictly.7 It overturned decisions very, very rarely, and essentially never overturned really old decisions. No doubt, this is partly because there just weren’t as many old decisions yet (the nation was young), partly because Congress was more inclined to step in and overturn erroneous precedents through new legislation (including the 14th and 16th Amendments), but likely partly because of strong belief in stare decisis.

When Lochner fell and the new progressive majority came into power, they smashed this old principle. From then on, precedent was never safe.

The second-most dangerous time in American history to be a precedent of the United States Supreme Court was the 33 years after Lochner fell. A progressive judiciary reshaped America (for better and for worse).

The most dangerous time in American history to be a precedent of the United States Supreme Court was the 35 years after Earl Warren retired, as the Burger and Rehnquist Courts grappled with Warren’s legacy.

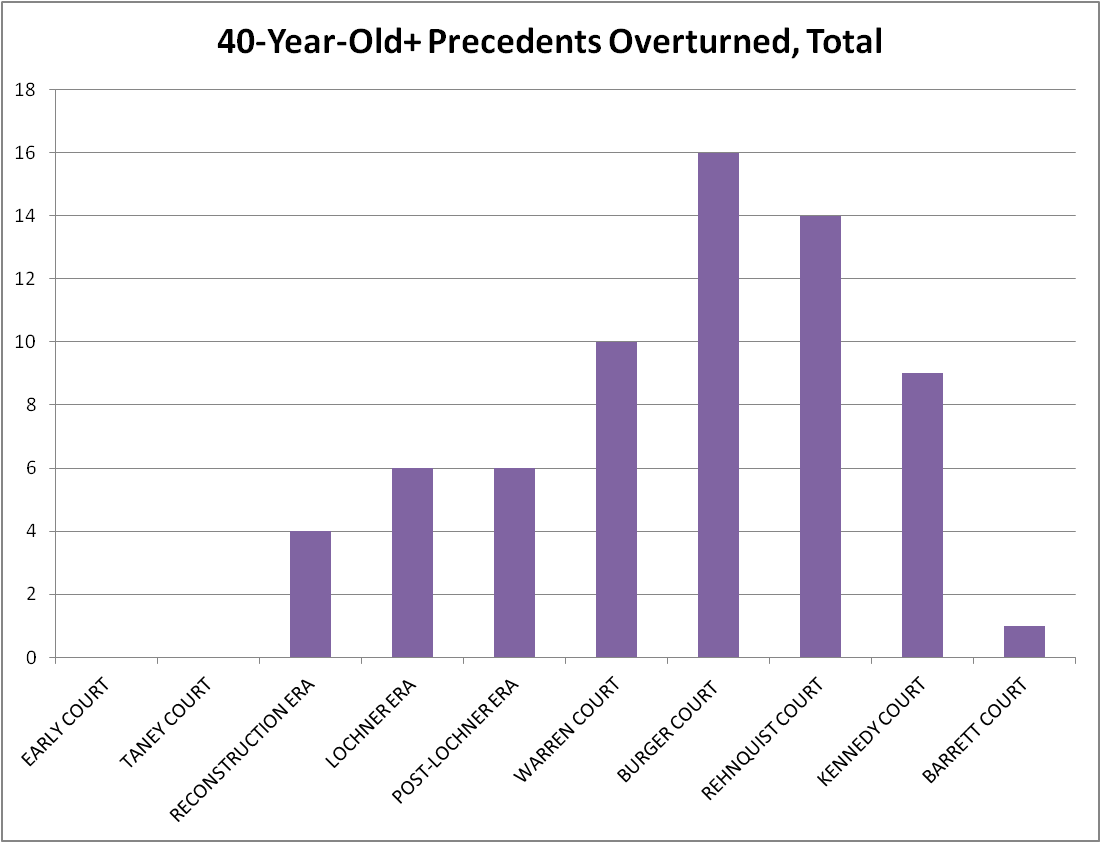

“Okay, James, but remember that Roe v. Wade was more than four decades old! That should count for something!”

Should it?

The Burger Court overturned three precedents that were over a century old. However, the Rehnquist Court wins the record: they overturned a case (Minturn v. Maynard) that was 136 years old at the time it fell.

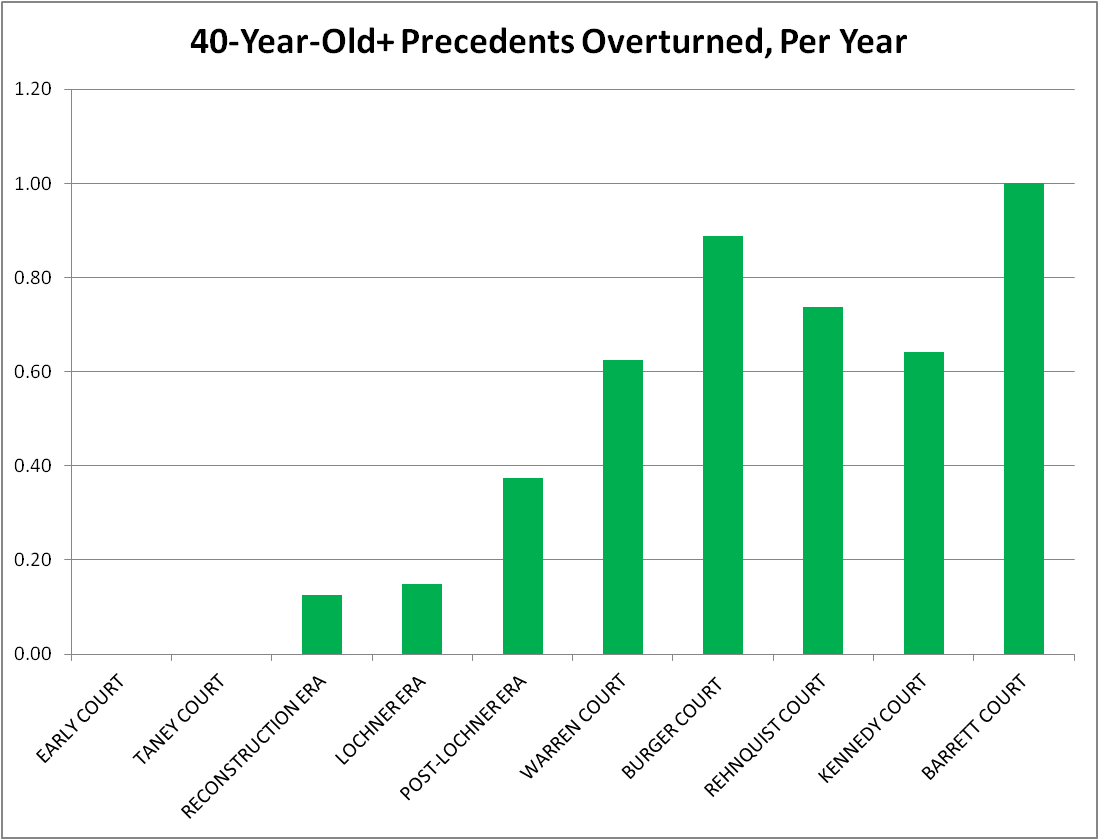

It’s true that, currently, the Barrett Court has the highest average annual rate of overturning 40-year-old precedents, but that’s largely due to small sample size: the Barrett Court has lasted one full year and, during that year, it overturned one longstanding precedent. In the Burger Court’s first year, it overturned three: a 60-year-old precedent, a 72-year-old precedent, and an 84-year-old precedent.

If the Barrett Court just refrains from overturning any 40-year-old precedents next term (as seems likely), next year’s version of this chart will show it in its usual position: less respectful of precedent than the Lochner Era and earlier Courts, but more respectful of precedent than all other modern Courts.

“But, James, the decisions the Supreme Court is overturning now are far more important than the ones it overturned back then. The old courts edited technicalities; the Barrett Court is gutting bedrock rules of our society!”

This is a subjective judgment, so answering it reaches beyond the empirical scope of today’s post.

I can only remind readers that, while the issues at stake in Erie Railroad v. Tompkins (1938; overturning a 96-year-old precedent) may not seem terribly momentous to you, that’s largely because the issue in Erie Railroad (federal common law) faded into the legal background in later decades, and you grew up in a world where no one contested it anymore. Ditto Gideon v. Wainwright, Wesberry v. Sanders, and Brandenburg v. Ohio, and Miller v. California. In short, you cannot look at these old decisions through the eyes of the present. You must identify whether the Supreme Court was overturning decisions of equal or greater importance to the America of the time.

“But, James, the Court used to overturn bad decisions! Now the Supreme Court is overturning good decisions!”

Maybe so.8

But now we aren’t talking about stare decisis. Stare decisis means sticking to a bad decision. If the decision was good, then you should be defending it honestly, on the merits, not dishonestly, through an interpretation of stare decisis that neither one of us believes in. But that’s another article.

What seems clear from the charts is that, based on the very limited data we have about the Barrett Court so far, the current conservative Court has not abandoned, or even weakened, stare decisis. Indeed, we have some very limited reason to suspect that it might be somewhat more respectful of stare decisis than some of its progressive predecessors. Of course, this could change (in either direction) as we collect more data about the Barrett Court in coming terms.

UPDATE 28 September 2022: It is the policy of De Civitate to include the underlying data set when I create charts of this sort, so you can catch me out in any Reinhart & Rogoff errors, or just criticize how I presented the information. I forgot to include the dataset in this post. You can access it on Google Sheets here: Age of SCOTUS Precedents When Overruled.

UPDATE 28 September 2022: When I edited in the above update, somehow Substack decided to resurrect a draft version of this post. That incomplete draft has been up on the blog for the past, I wanna say, eight hours, which is very embarrassing, because it used charts that I later threw out and redid in revisions and it was full of typos, incomplete sentences, and I believe an unfinished conclusion. Garbage! The correct version of the post has been restored, but I apologize to anyone visiting from reddit who saw the other version.

Technically, this is “horizontal” stare decisis. “Vertical” stare decisis is the principle that lower courts must obey the precedents of higher courts until and unless those precedents are overturned. It is, generally speaking, quite a bit stronger. Justice Barrett, while still a law professor, wrote about this in passing during a very interesting little paper called “Precedent and Jurisprudential Disagreement.” If you want to understand how precedent works, you will learn a lot reading Justice Barrett’s paper (even if you hate her)—certainly more than you will from reading my blog.

The easiest way to confound a conservative who’s always talked longingly about overturning precedents (and smashing the line of “substantive due process” cases) is to vehemently agree with him… then demand that the Supreme Court immediately overturn the clearly irrational and unconstitutional decision in Pierce v. Society of Sisters of Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, in which the Court concluded, resting on nothing but an absurd misinterpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, that parents have a constitutional right to direct the education of their children and send them to a school of their choice, including a parochial school.

On the other hand, the easiest way to perplex a progressive who’s furious about the Supreme Court’s recent “disregard” of precedent is to vehemently agree with him… then insist that Bowers v. Hardwick and Adkins v. Children’s Hospital should never have been overturned. After all, they were precedents, and the only reason either precedent fell was because the judges who handed them down were replaced by new judges with different views. Of course, when your interlocutor asks what those once-respected and long-lived precedents were about, you get to break the news: Bowers said that states could outlaw gay sex. Adkins declared minimum wage laws unconstitutional.

There were exceptions: Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (school vouchers) and Washington v. Glucksberg (assisted suicide) leap to mind, although Bush v. Gore was likely the most consequential and United States v. Lopez (limitations on Commerce Clause) the largest rightward doctrinal shift.

Meanwhile, though, progressives racked up far more big wins: Planned Parenthood v. Casey, Grutter v. Bollinger, Lawrence v. Texas, McConnell v. FEC, Kelo v. City of New London, Romer v. Evans, Gonzales v. Raich, Stenberg v. Carhart, Hill v. Colorado, and these are just the obvious ones.

Progressives still pretty consistently won the biggest cases, namely Obergefell v. Hodges (constitutional right to same-sex marriage), Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt (affirming and expanding a constitutional right to abortion), and NFIB v. Sebelius (the Obamacare case). Progressives won plenty of second-tier major cases, too (Boumediene, Kennedy, Glossip).

However, for the first time since the Lochner Era, conservatives began to accumulate a collection of landmark wins as well: Gonzales v. Carhart, Hobby Lobby, Shelby County, and Citizens United. Conservatives even won a first-tier major case, the biggest conservative court victory in almost a century: District of Columbia v. Heller, securing an individual right to bear arms.

Few of these wins (for either side) were particularly “clean,” because virtually all of them depended on the witless Kennedy (until the merely feckless Roberts took over swing-justice duties). The Court’s major decisions often followed a vague, slightly nonsensical internal logic, because Justice Kennedy demanded it.

The “Roberts hangover” of the Kennedy Era is reflected both in the Court’s overall jurisprudence and specifically in the precedents overturned during the “Roberts hangover” period: yes, SCOTUS overturned Abood in 2018 and Davis v. Bandemer in 2019, both conservative wins, but 2019 also saw the fall of Ward v Race Horse, a progressive win that killed a 123-year-old precedent. (The Roberts Hangover also finally saw Korematsu overturned in 2018’s Trump v. Hawaii.)

As the Library of Congress concedes in its methodology, identifying overturned precedents is an art, not a science. If a decision vitiates a precedent, clearly discarding its core reasoning and applications, but refuses to say the words, “We overturn this precedent,” has the precedent been overturned? What if people disagree about whether the old precedent has been gutted or not?

The Library adopts a restrictive methodology in order to avoid these difficult questions, and so its list does not include questionable overturns like Lemon v. Kurtzman or even Lochner v. New York. (Lochner was clearly destroyed, but was never formally overturned.) The Government Printing Office adopted a similarly restrictive methodology and came up with a similar but (as far as I can tell) not quite identical list. A graduate student with more time for this nonsense than I do (and/or a Westlaw subscription) might enjoy delving into how these results look if you adopt a broader definition of “overturning precedent.”

Where a single Supreme Court case overturned two or more prior precedents, I counted it as overturning only the oldest precedent. The overturned precedents were usually related, so counting them both seemed like double-counting.

…or, the Court saw itself as nearly infallible. After all, you only invoke stare decisis if you’ve made a mistake and don’t want to fix it!

Not really. But we’ll pretend for the sake of argument.

Thanks for this valuable contribution to current conversations! The later graphs show us something valuable that I hadn't seen elsewhere. The number of laws and institutions affected by each overturned precedent would be a worthy investigation for some grad student who can dedicate the time.

I do wonder about how you characterize stare decisis. You refer to it as a doctrine of keeping bad decisions, as amounting to an admission that something is wrong, but you don't want to fix it. That's not the way I've seen the term applied elsewhere. Stare decisis, as far as I have seen, applies where a court (or the Court) might rule in a variety of ways, without believing that precedent is necessarily wrong, but the court keeps to prior precedent in order to be fair and maintain trust in the law.

For example, the bar for prosecution for incitement to violence is extremely high in the United States. This precedent originally protected the violence of the KKK, but when leftists later came before the Court for inflammatory speech, stare decisis saw to it they were treated the same.

A legal team might rely heavily on stare decisis arguments when they suspect the judges before them do not agree with a prior ruling and will not buy their other arguments, but I'm not aware that invocation of the principle necessarily indicates a belief that the prior decision was in error. Not unless a Court believes that any decision other than what they would make with no precedent is bad, at which point we're discussing sheer arrogance more than legal reasoning.

How we read these graphs depends on how we contextualize history. The Constitution was written by wealthy White men in order to support their own long-term interests, and the early court made sure it did so. The lack of overturned precedents in the early court isn't just a function of the country being young; the range of judicial philosophies appointed would also have consistency within the range of interests they were designed to defend.

By the mid-20th century, we finally had enough people who were not White men in the electorate to filter into the dispositions and hermeneutics of the Supreme Court, thus resulting in readings that favored the American populace in general, at least sometimes--which necessarily means overturning precedents of a Court that did not. With the Barrett Court, thanks to a partisan re-alignment that enables a Senate majority to reflect the interests of well-off White men even with a minority of votes, we have a Court poised to return power to the race, class, and gender of people whom the framers intended. Out with the old overturnings, in with the new!

I have no doubt that you read this history differently.

Incidentally, I finally migrated over to Substack once you updated your old blog after some time. I'll probably be commenting on older posts now and again.