Welcome to all De Civitate’s new subscribers. I’m glad you’re here. Since my last thing was about The Law, I thought maybe I should do another Law post to settle everybody in before I get eclectic and do a post about The Orville: New Horizons or something. So!

While there are many, many contenders, this is my pick for the silliest argument for against fetal rights:

Yes, of course, obviously, we should be able to claim all our kids on our taxes.

Congress allows taxpayers to deduct certain income and take certain credits if they have children who are dependents. Congress has chosen to do this because parenting is difficult, exhausting, expensive, and potentially dangerous. Unlike a mere hobby, however, the bearing and raising of children benefits all of society. Parenting not only creates an entirely new and unique human being, infinitely valuable and inherently dignified, treasured by every code of human rights from the Constitution to the Universal Declaration; parenting also creates a future taxpayer, consumer, and citizen. We need a great many of them if we plan to keep, say, Social Security.1 For these reasons, Congress provides deductions and credits for parenting that it does not provide for, say, computer gaming.

Pregnancy is no picnic. It is difficult, exhausting, expensive, and potentially dangerous. The effects of pregnancy on women would take several pages to fully describe. From close personal observation, it is often a hellish ordeal. In my opinion, raising a toddler is far easier than raising a fetus.2 Pregnancy is a tough time even for the father, involving support of the suffering mother while preparing the household for the imminent arrival of a new member. (No stage of human development involves more cussing at furniture assembly instructions.) Pregnancy was among the hardest times in my life… and, mark my words, I had it a hundred times easier than my wife. Maybe a thousand.

Yet pregnancy is also an essential part of parenting. No adult has ever lived who wasn’t an infant first, so we provide tax deductions for raising infants. No adult has ever lived who wasn’t a fetus first, either. All the arguments for allowing tax deductions to parents of infants apply with equal or greater force to parents of unborn children.

You don’t have to agree that the fetus is a human person to recognize this. Even if the fetus is a mere “clump of cells” like a “toenail” or “cancer,” as the most reductionist anti-fetal arguments contend, parents with a bun in the oven are nevertheless engaged in a difficult, exhausting, expensive, and potentially dangerous project, on behalf of all society, that yields a creature of infinite value and inherent dignity, and which ensures Social Security will still have workers to support it in 18 years. So fix the law! Give pregnant moms their damn child tax credits, Congress!

…unless… unless Congress already has?

Seriously: who says I can’t claim my unborn child as a dependent on my tax return? Lots of online blog posts from different tax services say so, but they don’t cite sources. This one from H&R Block is typical. What does the law say?

Unborn Children & the Internal Revenue Code

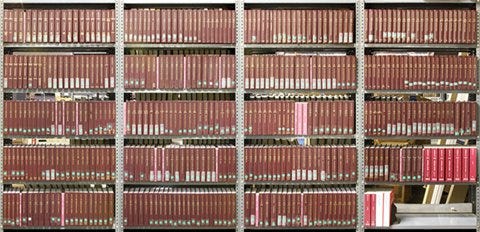

Many people are intimidated by federal law and think that you have to be a lawyer to read it. Federal law is actually very simple: all federal law is printed in a single very long book called the United States Code. The U.S. Code (or “USC”) is divided into chapters called “Titles.” Each title deals with one very big subject, like “Title 13: The Census” or “Title 35: Patents.” Each title is then divided into chapters, which are divided into sections. The book is written in plain, precise language. It has to be, or citizens and courts wouldn’t be able to obey it. The main problem with the book is that it is very, very long.3 No one seems to even know how long:

Fortunately, we have the Internet now, so who cares? You can just look up any part of the USC online. Let’s do that!

The USC says that the child tax credit and the child tax exemption are awarded to each “qualifying child” in the household.4

“Qualifying child” is defined in Title 26 (The Internal Revenue Code), Chapter 1 (Normal Taxes and Surtaxes), Section 152 (Dependents Defined) with the following language:5

(1) The term “qualifying child” means, with respect to any taxpayer for any taxable year, an individual—

(A) who is a child of the taxpayer or a descendant of such a child

(B) who has the same principal place of abode as the taxpayer for more than one-half of such taxable year,

(C) who is younger than the taxpayer claiming such individual as a qualifying child and has not attained the age of 19 as of the close of the calendar year in which the taxable year of the taxpayer begins,

(D) who has not provided over one-half of such individual’s own support for the calendar year in which the taxable year of the taxpayer begins, and

(E) who has not filed a joint return (other than only for a claim of refund) with the individual’s spouse under section 6013 for the taxable year beginning in the calendar year in which the taxable year of the taxpayer begins.

Your “child” is defined later on in the same law (152(f)(1)) as your “son, daughter, stepson, stepdaughter, or eligible foster child”.

In plain English: suppose you are filing your taxes on January 1st. You are pregnant, aka “with child,” and have been for a while. In the previous year, was your unborn child…

…your child, aka your son or daughter? YEP.6

…younger than you? YEP.

…under the age of 19 at the end of the year? Unless you’ve had a 79-trimester pregnancy, YEP.

…not providing more than half of his or her own support? Children under age 3 (born or unborn) can’t provide their own support, and the unborn kid is definitely getting nutritional support from Mom whether Mom likes it or not, so this is another YEP.

…not filing a joint return? Children under age 3 (born or unborn) are incapable of filing joint returns, so YEP.

…living in the same place as you? The kid’s literally inside your body, so, YEP, the kid shares your home address.

…living there for more than half the year? MAYBE.

Most of these are extremely clear-cut.

Someone might object that your “unborn child” is not really your “son or daughter” within the meaning of the law, or that it’s ambiguous… but, no, it’s actually completely unambiguous.

Unborn Children & Ordinary Meaning

“Son” and “daughter” are not further defined in the statute, so we treat them according to their ordinary English meaning at the time of the statute’s adoption (2004). The definition of “daughter,” per the Oxford English Dictionary, is “a girl or woman in relation to either or both of her parents; a person’s female child.” (The definition of “son” is identical, except the gender is swapped.) So the definitions rest on the dictionary definition of “child.”

There are only three definitions of “child” listed in the Oxford English Dictionary that are relevant to our inquiry. (I have listed all of the 20 irrelevant definitions in this footnote7 so you can check my work.)

(a) “An unborn or newly born human being; a fetus, an infant.”

Clearly, an unborn child meets this definition. PASS.(a) “A young person of either sex, usually below the age of puberty; a boy or girl.”

The ‘it’s a girl!!’ tags on all my childrens’ ultrasounds, which were added by professionally trained ultrasound technicians, show that, yes, unborn children are boys and girls, certainly below the age of puberty, and that literally everyone knows this, including all medical professionals, at least when they aren’t consciously thinking about the effect that acknowledging this could have on abortion rights. PASS.(a) “As correlative to parent: A son or daughter (at any age); the offspring of human parents. Also as a form of address. In Old English bearn bairn n. is more common in this sense.”8

First, is an unborn child “the offspring of human parents”? The relevant non-circular definition the OED supplies for offspring is “the product or products of sexual reproduction in animals or plants,” so… yep! Even you people who insist on calling the fetus the “products of conception” gotta give us that one. Second, does an unborn child have “any age”? My gestational chart says yep! This definition clearly includes unborn children. PASS.

So, in 23 definitions and sub-definitions, the OED has exactly 3 definitions of “child” that seem relevant to the definitions of “son” and “daughter” in the child tax exemption law. Unborn children unambiguously meet all those definitions. This is a comprehensive dictionary of ordinary global English usage, gang.

Don’t trust the British? Fine. Try the contemporary Merriam-Webster entry. The closest Merriam-Webster gets to ambiguity is in its second sense of “child,” a sense not quite matched by the OED:

2 a : a young person, esp. between infancy and youth

This sense still includes unborn children, just not in the “especially” clause. Also excluded from the “especially” clause: adult children, older teens. 26 USC 152(d)(2)(A) makes clear that Congress does not intend to exclude adult children from its definition of “children.” Therefore this “especially” clause cannot be used to exclude unborn children, either.

The other Merriam-Webster senses of “child” are slam-dunks for the unborn:

1 a: an unborn or recently born person

…but they mostly repeat the OED, so I won’t belabor the point. I trust it is clear: trying to find an authoritative “plain, everyday meaning” of “child” that doesn’t include unborn children is a fool’s errand. In general usage, unborn children are children. If you don’t like it, consult linguistics.

But maybe Congress in 2004 meant “son or daughter” in a more legal sense? So maybe we should look to their legal definitions? Here’s Black’s Law Dictionary:

Here’s their definition of “daughter”:

A parent’s female child; a female child in a parent-child relationship.

And “son”:

1. A person’s male child, whether natural or adopted; a male of whom one is the parent. 2. An immediate male descendant. 3. Slang. Any young male person.

And “descendant”:

One who follows in the bloodline of an ancestor, either lineally or collaterally.

…although I’m fond of the old definition from the 2nd Edition:

[o]ne who is descended from another; a person who proceeds from the body of another, such as a child, grandchild, etc., to the remotest degree.

This is not even a close question. Is the child in the womb a descendant of the mother and of the father? Yes, obviously. Are they “the young of the human species… under the age of puberty”? Yes, obviously.

Even if you don’t think the unborn child is a “full human person” with whatever moral value you ascribe to that term, this “clump of cells” has a sex. It has parents. It has “proceeded” from the body of the father and mother (in the sense “procession” is used here9) to form its own body, and it is plainly a genetic descendant in the “bloodline” of both parents.

Perhaps the most decisive argument, however, came from my seven-year-old daughter. On Saturday night, I was subjecting her (under protest) to an explanation of one of the relevant court cases. (We were in the car, so captive audience.) As I articulated one of the statutory arguments, she interrupted me. “Dad, that isn’t how I would put it at all.” I asked her how she would put it. She answered, “Well, look, I would just ask the judges, if it’s not her child, what is it? An alien?”

Enough said!

Unborn Children & the Residency Requirement

Still, there was one “maybe” on our list of qualifications for the child tax credit: did the child live with you for more than half the year? Not all unborn children do, after all… and an IRS special rule complicates matters!

The IRS has a special rule that any baby born alive at any time during the year (even at 11:59 PM on December 31st) counts as living with you for more than half the year, as long as it lived with you (or in the hospital) after birth. This is a generous rule, and we’ll talk more about it in a little while, but, for now, we have to notice what this means for the unborn child we’re trying to claim as a dependent, assuming a normal 37-week10 pregnancy:

Babies conceived in January, February, March, or the first few weeks of April already qualify for the child tax credit under this special rule, because they will be born before December 31st.

Babies conceived in July, August, September, October, November, or December do not qualify for this credit because they did not live with Mom for “more than one-half [the] taxable year.” Winter conceptions may meet this requirement for the following year… but they will qualify for the credit that year anyway under the special rule, because they will be born in that year as well.

This only leaves babies conceived in May, June, and maybe the last week of April. These kids will live with Mom for “more than one-half [the] taxable year,” but will not actually be born (automatically qualifying them under the special rule) until the following year. These kids are the only unborn children who potentially qualify for the child tax credit but aren’t currently being awarded it.

My kids were conceived in October and March, respectively. I was unable to claim the first on my taxes because she did not live with us for “more than half [the] taxable year”: November and December is, of course, only two months, not six.11 I should have been able to claim my second daughter as an unborn child, because she did live with us in utero for almost eight months of the calendar year, but the IRS special rule meant I could already claim her as a born child when she arrived (prematurely) before year-end.

However, if we ever conceive a child in May or June, with a pregnancy lasting into the following calendar year, I decided years ago: I’m gonna claim that kid on my federal income tax return, because federal law says in plain language that I am allowed to do that. If the IRS decides to come after me, I will fight them in court.

How might I fare? How might you?

I warn you: I am about to plunge into a rabbit hole. I have already shown how, on a plain reading of the federal statute and the ordinary English language, your unborn children should already count as “qualified children” for federal child tax benefits. If you’re satisfied with that answer, stop here. Going forward, my intention is to arm a hypothetical future pregnant taxpayer with all the information she may need to decide whether to take on the IRS, plus tools to help her win. (But maybe consult an actual lawyer before you try this at home.)

If you want all the details on why the IRS doesn’t count our unborn children as dependents (and why they’re wrong not to), read on, but, heads up: here be dragons.

Unborn Children & the Code of Federal Regulations

The United States Code is not self-executing. Congress tells us how much we owe in taxes, but the Executive Branch, in this case the Internal Revenue Service, has to actually collect the money. The IRS must write the actual forms, address weird edge cases that don’t easily fit Congress’s language, and set up the physical system taxpayers use to pay their taxes.

Congress doesn’t need to get bogged down in these technical details. They have expressed the Law of the Land; they now delegate the details of execution to the executive branch. 26 USC 7805 authorizes the IRS to “prescribe all needful rules and regulations for the enforcement of this title.”

Those rules and regulations are published in another book called the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Every rule and regulation issued by the White House goes into this book, and stays there until a future White House takes it out.

The Code of Federal Regulations is intended to implement the United States Code. By necessity, the federal agencies sometimes have to interpret the U.S. Code in the process. However, Congress makes the laws in this country, not the White House. The CFR cannot contradict the U.S. Code. It also cannot go beyond what the U.S. Code commands—at least, not without specific authorization from the U.S. Code itself.12

It can be very difficult to find things in the CFR, but the CFR’s clarifications of the “qualifying child” law are at 26 CFR 1.152-1, -2, -3, and -4. Most of it is irrelevant to our issue. It addresses unusual situations like adopted kids, claiming the kids after a divorce, whether scholarships count as “support,” people born in the colonies back when the U.S. had colonies, and so on. Only two chunks are relevant to us.

First is this one (in 1.152-2(a)(1)):

[T]o qualify as a dependent, an individual must be a citizen or resident of the United States[.]

Uh-oh: unborn children are not citizens of the United States. The Fourteenth Amendment guarantees citizenship when a child is born (or naturalized). The Amendment doesn’t seem to prevent Congress from conferring citizenship on others. Congress could confer citizenship on unborn children, just as Congress could confer citizenship on the Welsh. However, Congress has not, to my knowledge, done so.

On the other hand, unborn children are clearly residents of the United States. They are physical creatures that inhabit a location. That location is within the borders of the United States (not Timbuktu, not international waters, not Mars). So we’re fine.

The second relevant chunk is 1.152-1(b), which is, officially, the source of the “special rule” that a child born late in the year still “counts” for the child tax exemption. Here’s the legal language:

The fact that the dependent dies during the year shall not deprive the taxpayer of the deduction if the dependent lived in the household for the entire part of the year preceding his death. Likewise, the period during the taxable year preceding the birth of an individual shall not prevent such individual from qualifying as a dependent under section 152(a)(9). Moreover, a child who actually becomes a member of the taxpayer's household during the taxable year shall not be prevented from being considered a member of such household for the entire taxable year, if the child is required to remain in a hospital for a period following its birth, and if such child would otherwise have been a member of the taxpayer's household during such period.

Here we start to see how rickety the different pieces of federal law can be. This bit of the CFR cites “section 152(a)(9)” of Title 26 of the U.S. Code. However, section 152(a)(9) was deleted in 2004!13 It’s gone! This regulation was written in 1960 and was last updated in 1971. It’s out-of-date.

It’s not simple to interpret a regulation that references a law that no longer exists. For a little while, I thought “section 152(a)(9)” should be interpreted to mean “section 152(d)(2)(H),” because that’s where most of the actual 152(a)(9) got moved to. But that doesn’t fit with how the IRS is actually enforcing this regulation. I’m going to set aside these apparent ambiguities for tonight, although it’s very… interesting… to try and unpack how (and if!) each sentence of 1.152-1(b) matches up with actual law. Here’s what the IRS itself seems to think this regulation means:

If your dependent is born or dies during the tax year, you only count the time before the dependent’s death or after the dependent’s birth. Dependent children still have to meet the “lived with you for half the year” test, but, for them, that means “lived with you for half of the time this year before dying or after gettin’ born.”

For example, if a child is born to you one month before the end of the tax year, the IRS thinks he “lived with you for half the year” as long as he lived with you for at least two weeks out of that month. Bonus: baby’s time spent in the NICU counts as living with you.

But, wait. Why would the IRS treat these events the same way? Death ends your life, so it makes some sense that you should only count the time you actually spent alive as your “year.” But birth doesn’t begin your life, so why would you only count the time after birth?

Hang on, does the IRS realize that fetuses are alive?

It does not! The IRS—on the basis of absolutely no federal statute, it should be noted—has concluded independently that life begins at birth. Unborn children are therefore ineligible for tax benefits. That is the source of all those H&R Block posts saying you can’t claim an unborn child, and that is our problem.

Unborn Children & Case Law

As we’ve seen, the White House’s job is to execute the laws of the land, but, in order to do this job, it must sometimes interpret the laws. Mainly, this is done through the Code of Federal Regulations. However, federal agencies must also deal with every individual situation in the United States. Some of those are strange or surprising, they are not covered by general regulations, and the agency has to make a judgment call. These interpretive judgment calls, made on a case-by-case basis, come in many forms, from interoffice memos to formal agency rulings to pseudo-court cases.

In 1940, the IRS decided that human life begins at birth. This earth-shaking development in the biological sciences occurred in a case called Wilson v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, before the Board of Tax Appeals. Although the Board was not a court (and clearly not advised by biologists), it functioned much like a court, and its rulings have been respected as precedents.

Wilson v. Commissioner

Although the tax laws back in 1940 were very different, Mr. Lloyd Wilson was trying basically the same thing I’m suggesting: he attempted to count his unborn child as a dependent. Ernest Van Fossan, hearing the case for the B.T.A., was having none of it:

The word "person" as used in section 25(b)(2) [of the Internal Revenue Code of 1932] is to be taken in its normal, everyday sense of a living human being, a man, woman, or child, an individual…. The interpretation which petitioners suggest is so obviously strained as to merit little discussion. Doubtless in this fact is to be found the reason why this question has never heretofore been presented to the Board. It may also account for the paucity of authority in petitioners' brief.

If an unborn child is not a “living human being,” then what is it? (An alien?) Van Fossan offers a suggestion:

[the fetus] was only a part of her mother, and not a human being or person.

The IRS later treated this suggestion as binding, applying it to stillborn children. You get no dependent exemption for a stillborn baby at any gestational age because, according to the IRS, she was never a living human being, only a part of her mother.

Van Fossan airily dismisses the entire body of common-law rights for unborn children in a single sentence:

Nor is the fact that, by common law and generally by statute, a child [in utero] is deemed to [actually exist] for the purpose of inheritance for its own benefit persuasive here. The credit here claimed is not for the benefit of the child but of the parents.

Van Fossan does not give any reason why the distinction between “the benefit of the child” and the “benefit of the parents” matters, legally, to the very legal existence of the child. It is certainly not obvious, and does not seem persuasive. It seems more like Van Fossan was trying the classic lawyer’s trick of dismissing precedents you don’t want to apply by coming up with some baseless “distinction” that allows you to ignore the precedents you don’t like. It’s very hard to say, though, because Van Fossan gave literally no explanation.

The whole decision is barely half a page long, so go ahead and read it. It’s as sobering as it is perfunctory.

Nevertheless, this single, half-page ruling has served as the basis for generations of IRS rules and rulings. Wilson is at the root of the “special rule” that treats birth as the start of life. It has informed the language used in IRS Publication 501 and its predecessors for at least 50 years. (I didn’t look back further.) It was the basis for an IRS ruling in 1973 that a child born alive is eligible for the deduction, even if she dies one second later—but stillborn babies are never eligible.14 It informed decisions about whether a surrogate mother or the child she carried could be a dependent in the mid-2000s.15 Wilson’s finding that unborn children are not “living human beings” is, for tax purposes, the law of the land today.

Faulkner v. Commissioner

Curiously, another B.T.A. decision just a few months after Wilson, Faulkner v. Commissioner, dealt with a gift to a trust set up on behalf of an unborn child. Faulkner, decided by a different judge, was forced to again consider whether an unborn child was a “person.” This time, though, citing quite a bit of prior case law, Faulkner upheld the unborn child’s personhood. I particularly liked Faulkner’s quotation from the “famous case” of Thellusson v. Woodford (a British case from 1799 that had substantial persuasive influence on both sides of the Atlantic):

Why should not children en ventre sa mere be considered generally in existence? They are entitled to all the privileges of other persons.

Faulkner went on in this vein for several pages before reaching its legal conclusions, thereby supporting its conclusions with evidence rooted in cited law.

Faulkner argued that it didn’t contradict Wilson. It relied on Wilson’s own unconvincing “fetuses are legally people for their own benefit, but not for their parents’ benefit” distinction. (In fairness, there were some precedents that pointed in that direction, although other precedents pointed in the opposite direction.) Faulkner itself was a case where the gift in question was given for the fetus’s benefit, and stressed that point… while glossing over the fact that the gift generated a tax benefit for the fetus’s mother as well, calling its reliance on this distinction into question.

Faulkner was appealed to the full board and upheld by a 12-4 vote.16 Nevertheless, Faulkner was eventually overturned by new IRS regulatory rulings. Faulkner fell and Wilson survived. Understanding why the IRS chose to follow Wilson over Faulkner would probably require a dissertation on interoffice politics in the IRS of the 1940s and ‘50s. In an invaluable 1995 paper, Paul L. Caron explained the hows and whens of Faulkner’s destruction, but the whys remain a mystery to me. Whatever the reason, it happened, and, as a result, the IRS says you can’t claim your unborn child on your taxes.

Cassman v. United States

In 1994, Wilson was reaffirmed in Cassman v. United States, decided by Judge Wilkes Robinson of the United States Court of Federal Claims. In this case, Mr. & Mrs. Michael C. Cassman attempted to claim the child tax exemption on behalf of their then-unborn son, Jonathan Cassman.17 The Cassmans appear to have been represented by tax lawyers, not people with experience in the field of unborn law. They appear to have failed to press several arguments that they probably should have made. They lost.

Judge Robinson’s Cassman opinion is a better decision than Wilson. He explains himself, at least. Robinson defers to Wilson on stare decisis grounds:

Wilson represents a federal judicial precedent entirely on point with the essential issues in this case, and plaintiffs have failed to make a compelling argument as to why this court should disregard that precedent.

A “compelling argument” is required because, under stare decisis principles, it is not enough to show that an earlier decision was probably wrong. One must generally show that it was egregiously wrong, or that its precedential value has been eroded by other developments, or that the precedent has had other detrimental effects. Thus, a “compelling argument.”

Insisting that unborn children only ambiguously meet the definition of “person” or “individual,” Judge Robinson then analyzed legislative history to try and determine whether Congress intended to include unborn children within their scope or not. He concludes that, because a related provision applying to U.S. colonies operated only after birth, it must have been Congress’s intention that the entire child tax exemption must operate only after birth.18

This kind of legislative analysis was supported by precedents at the time, although it is disfavored by the majority of the judiciary today. It only makes sense if you concede Robinson’s argument that the definition of “person” is ambiguous. Textualism insists that the intent of the lawgiver is not the law of the land; the law is the law of the land. As Justice Kagan has said, “We’re all textualists now.” This privileging of legislative text over legislative intent was the core of Bostock v. Clayton County’s protections for gay and trans employees. Still, given his premises and the time period he lived in, Robinson’s legislative history was a perfectly serviceable piece of judicial analysis.

Cassman further notes that, in Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court specifically rejected the proposition that unborn children are “persons” within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. Judge Robinson wisely declines the plaintiffs’ invitation to interpret “person” here as meaning something different than it does in the Fourteenth Amendment.

On the other hand, Robinson sometimes walks you right up to the point where he intends to make a convincing argument, then just skips past the argument to the conclusion. The plaintiffs made the same argument that I did earlier: that their son Jonathan was not a citizen of the United States while in utero, but he was obviously a resident of the United States, because he literally lived inside his mother’s womb, and she was a resident of the United States the whole time, so where else is he going to be a resident of? (Outer space?) Robinson draws a fantastically illogical conclusion:

Plaintiffs argue that Jonathan Cassman was a resident of the United States prior to his birth because his mother was a resident, and they ask the court to take judicial notice of the fact that it would have been physically impossible for the mother to be a resident and her unborn child not to be a resident. This argument is without merit. The court cannot justify viewing an unborn child as “residing” anywhere [Ed. What?! Why not? Where are the dictionary citations? What’s the reasoning?]; moreover, it would also be unreasonable for the court to view the unborn differently for the purposes of the terms “citizen” and “resident” [Ed.: WHY?! Does Robinson think illegal aliens in the United States aren’t “residents” with certain rights of their own?] The court declines to accept plaintiffs’ interpretation and concludes that Jonathan was neither a “citizen” nor a “resident” of the United States on December 31, 1991.

So Jonathan was a resident of… I guess nowhere? This unborn child could (and presumably did) receive medical care in the United States, because he physically lived in the United States and not anywhere else. But he did not actually “reside” here, according to Judge Robinson. Are both twins in a pair of conjoined twins “residents” of the United States, or just one of them?

Robinson also notes Congress’s requirement that children “not [have] attained the age of 19” in order to be eligible for the exemption. He then concludes, out of nowhere, that the mere reference to age (which is colloquially based on birthdate) means Congress must have meant to exclude all ages before birth.

Having agreed with absolutely none of the Cassmans’ legal arguments, the Court is able to put the icing on the cake with a public policy argument:

…the court is concerned with the potential for increased administrative burdens both on the I.R.S. and on the taxpayers. A live birth, by operation of state and local law, results in the issuance of a birth certificate, which is a universally accepted and administratively efficient document of identification. In the present case, it is no coincidence that the principal evidence that plaintiffs have submitted — apart from an affidavit — to indicate that Mrs. Cassman was pregnant during 1991 is the birth certificate issued for her son in July of 1992. The birth certificate itself demonstrates that plaintiffs have a son. If the court held, as plaintiffs urge, that the dependent exemption was available as of the date of conception, then the exemption would be available for pregnancies that never resulted in live births and the issuance of a birth certificate, including those pregnancies ending in miscarriages, induced abortions, and stillbirths. In the absence of any clear evidence of congressional intent to do otherwise, the court must spare taxpayers and the I.R.S. the administrative burden of establishing that such pregnancies occurred or did not occur.

In re Fleishman

Finally, in 2007’s In re Fleishman, the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Division of Oregon reinforced Cassman by citing it in a dispute over whether an unborn person counted as a member of a “household” for purpose of Title 11 (Bankruptcy), Chapter 13. Judge Randall Dunn defers to the Census definition of “household,” notes that the Census does not count unborn persons as part of a household, and cites both Wilson and Cassman. Specifically, Dunn favorably cites the public policy argument at the end of Cassman and the “unborn children don’t reside anywhere” argument from the middle.

(One further case in this cluster, In re Pampas (2007) also rejects unborn children as members of a household, but does no meaningful analysis.)

Fleishman and Pampas are of little interest to us, as they deal primarily with the definition of a “household” under bankruptcy law, which has little directly to do with the definition of a “child” in the child tax credit, and neither case adds to the analysis of Cassman. I note them mainly for thoroughness.

Wilson and Cassman, however, are some pretty bad precedents for us, in our hypothetical lawsuit against the IRS. It’s therefore worth examining why they are so weak.

Wrong the Day They Were Decided…

Wilson was egregiously wrong the day it was decided. It is not a reasoned judgment of judicial character. Ernest Van Fossan gives no sense that he felt any obligation to try to produce one. Only the first sentence of Member Van Fossan’s19 discussion is correct:

The word "person"... is to be taken in its normal, everyday sense of a living human being, a man, woman, or child, an individual.

Yes! This is precisely my point. Undoubtedly, it was Mr. Wilson’s point as well.

Mr. Wilson's unborn child was, objectively, both a "living human being" and a "child". This was known, beyond a shadow of a doubt, even by the more primitive medical science of the 1940’s. Nor has the meaning of either word changed substantially since then; contemporary dictionaries reflect the same inclusive meanings they do today.20

Nor is Member Van Fossan correct that the "normal, everyday" sense of "person" excluded unborn children. On the contrary, in 1941—barely a year after Van Fossan handed down his decision—the federal government quietly declared that unborn children were "persons" for the purposes of receiving welfare payments under the Social Security Act, apparently on the grounds that this was how the word was generally understood. This policy would continue for 30 years, right up until changes in law made it much more expensive. When it realized how much more expensive, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare *ahem* discovered reasons to exclude the unborn.21

As Faulkner shows through authority after authority, there was also ample common law material supporting substantial legal rights for fetuses, even in 1940. The Faulkner decision approvingly quotes (among others) the 1797 English case Long v. Blackall22:

An [unborn child] is capable of having a legacy, or a surrender of a copyhold estate, made to it. It may have a guardian assigned to it, and it is enabled to have an estate limited to its use, and to take afterwards by such limitation, as if it were then actually born. And in this point the civil law agrees with ours.

Contrary to Wilson's literally baseless assertion, these common law rights were not a mere rule of construction, nor were they strictly limited to circumstances where the fetus was the sole beneficiary. Faulkner itself, despite its protest, was a case where the fetus was not the sole beneficiary. Yes, some cases, like those excluding stillborn children from inheritance, did point in that direction—and, while those cases had been reversed in England, they remained a rule in at least some American jurisdictions. (Member Van Fossan might have favored us by citing one.) However, others, like the aforementioned Thellusson, instead contended that unborn children are already "entitled to all the privileges of other persons." For a more comprehensive survey of the state of the law of fetal rights circa 1940, consult William J. Maledon’s 1971 paper, “Law and the Unborn Child.” SPOILERS: it is not a winner for Wilson.

And so every sentence in the Wilson rationale after the first is either completely wrong, entirely unsupported, or—most often—both. That may sound damning, but not really: there's only six more sentences in the opinion, and one of them is a quotation. It is impossible to pick Wilson apart, because there is simply nothing there.

The central claim in Wilson is, “The interpretation which petitioners suggest is so obviously strained as to merit little discussion.” As we have proved, this is wrong. Member Van Fossan was a handsomely paid Article I judge who wrote a half-page opinion that set policy for four generations which denied child welfare credits to untold millions of Americans. I am a blogger writing 82 years after the fact, without a law degree, mostly writing and researching this article weeknights, well after midnight, because I have a day job and kids (and a nasty cold I can’t shake). I have spent a great deal more energy demonstrating Member Van Fossan is wrong than Member Van Fossan spent bothering to demonstrate that he was right. He deserves no more of our attention.

The Cassman court of 1994 turned in a reasoned judicial decision worthy of respect as an actual precedent. However, in the name of stare decisis, it also turned a blind eye to all Wilson’s deficiencies. One can't help but wonder whether the famously distortionary lens of abortion law23 played some role in Cassman as well. Cassman's affirmation of Wilson added nothing to Wilson that might repair it. Cassman merely failed to see compelling reason to overturn Wilson. The court deemed one particularly awkward quotation in Wilson to be obiter dicta (without legal force), extended Wilson’s definition of “person” to the word “individual,” and otherwise gave Wilson its blessing.

What Cassman does add to our case (aside from its bizarre assertions about “residency”) is its brief discussion of Roe v. Wade, which stated that a fetus is not a "person" within the 1868 meaning of the 14th Amendment. This was a reasonable discussion! Roe was binding precedent on Judge Robinson’s court, and I have found little reason to believe that the meaning of "person" changed substantially between 1868 and 1932 (when the tax code in Wilson was enacted), or between 1932 and 1986 (when the tax code in Cassman was re-enacted).

However, Robert George and John Finnis, among others, have shown that Roe likely erred in this finding. In fact, it is more probable that unborn children are included within the word "person" as the word was legally understood in 1868. Moreover, it is probable that Roe will be overturned in its entirety in a matter of weeks, ending its precedential value.

Wilson was wrong the day it was decided. Cassman should not have followed it. Both decisions deserve to be overturned on the force of facts already available when they were handed down.

…And They Are Wronger Today

Yet the facts have changed substantially. The foundations of Cassman and Wilson, fragile as they were, have further “sustained serious erosion” since they were written (to borrow the words of Lawrence v. Texas).

In the years since Cassman was decided, Congress has clearly shown (on more than one occasion) that it recognizes fetal life. In the Unborn Victims of Violence Act of 2004 (codified at 18 USC 1841), Congress recognized “unborn children” as the legal victims of a wide variety of federal crimes—including murder—if those crimes should lead to the injury or death of the “unborn child.” Congress defined “unborn child” in that act as “a member of the species homo sapiens, at any stage of development, who is carried in the womb.”

This law stopped short of identifying unborn children as “persons,”24 but it is difficult to argue that the phrase “child, who is in utero” does not at least legally identify unborn children as “children.”

Moreover, in the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003,25 Congress explicitly made a finding of fact that a “living, unborn child” exists and is a victim of the procedure banned by the Act. The law refers more than once to a “living fetus,” which makes untenable Wilson’s suggestion that the fetus is merely “part of her mother” rather than itself “living.” The Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act also makes the first explicit reference I can find in the U.S. Code to the “mother” and “father” of the living fetus. If a “daughter” is defined (as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it) as “a girl or woman in relation to either or both of her parents; a person’s female child,” then Congress has authoritatively identified the “living fetus” as a “child” who exists “in relation to both of her parents.”

Furthermore, some 38 states now have fetal homicide laws, 29 of which apply immediately at fertilization. A great many of these laws were either first enacted or substantially modified after Cassman. Many more of them explicitly define an unborn child in terms that satisfy the language of the federal child tax exemption. Here is a short excerpt from the law in Kentucky (passed in 2004):

07A.020 FETAL HOMICIDE IN THE FIRST DEGREE

(1) A person is guilty of fetal homicide in the first degree when: (a) With intent to cause the death of an unborn child… he causes the death of an unborn child;…

(2) Fetal homicide in the first degree is a capital offense.

07A.010 DEFINITIONS.

(a) “Unborn child” means a member of the species homo sapiens in utero from conception onward, without regard to age, health, or condition of dependency.

State court precedents on this question have grown more favorable as well. (That’s not even close to a comprehensive survey. It’s just a taste.)

It is true that none of these enactments directly bear on tax law. Yet each time Congress shows that it considers the unborn to be children, the burden of proof mounts for supporters of Wilson to show that Congress didn’t intend to count them as children for tax purposes—especially when the dictionary evidence points so decisively against them. Each time a state shows that its understanding of the ordinary English word “children” includes unborn children, that burden ratchets a little higher. To date, no one appears to have offered any plausible positive evidence to meet this burden at all.26 (Wilson and Cassman both reached their conclusions primarily by placing the burden of proof on the other side, not by offering any positive evidence of their own.)

Finally: all of the federal action mentioned here (and much of the state action) occurred before October 4th, 2004. This date is important, because, on October 4th, 2004, Congress enacted the Working Families Tax Relief Act of 2004. This law rewrote from scratch the legal definition of dependents. This was the first time the law had been comprehensively overhauled since the 1950’s. The current, binding definition of a “qualifying child” in federal tax law was created that day.

This matters for statutory analysis, because the first rule of textual analysis is that words in a statute bear the public meaning that they held at the time the statute was passed. The meaning of “child” enshrined in 2004’s tax law must, therefore, be understood to have been at least informed by the understanding of “child” Congress had only recently enshrined in the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act (November 5th, 2003) and in the Unborn Victims of Violence Act (April 1, 2004). It should also be informed by the burgeoning recognition of unborn children in the states, which presumably reflected awareness of unborn children in common language as well.

It also matters because the 2004 law changed the key word. In Wilson, dealing with the 1932 tax code, the key word was “person.” In Cassman, dealing with the 1986 tax code (with language dating to 1954), the key word was “individual,” which Cassman treated as synonymous with “person.” Today, however, thanks to the 2004 revisions, the key word is “child.”27

While the simplest definition of “person” or “living human being” is simply “a living member of the species homo sapiens,” many people object to this definition, because it counts as “persons” certain members of homo sapiens that they don’t think are worthy of the human rights recognized in full persons. These objectors argue that “personhood” is attained only when a homo sapiens attains some developmental milestone such as brainwave activity, viability, acceptance by the community, or language. This is a philosophical argument (really a kind of secularized delayed ensoulment argument) and it is very difficult to resolve.

“Child” is considerably less charged. Even if we conceded that a fetus is not a “person” or “human being,” “child” is a word that merely notes a predominantly biological relationship between one organism and one or more other organisms. The fetus, even if not a “person,” is nevertheless the “child” of its parents. Congress has acknowledged this very obvious fact. It is about time the Internal Revenue Service does the same.

Final Trifles

It feels like a betrayal of my purpose not to mention a few final legal points.

First, the IRS will undoubtedly assert that its interpretation (that “child” and “son or daughter,” as used in Congress’s statute, does not include unborn children) is entitled to judicial “Chevron deference.” A response to this would require full development in any actual lawsuit, but, very briefly:

Chevron only applies when there is ambiguity in the statute. This statute is not ambiguous. No reasonable reading excludes the unborn. (Once again, consult the dictionary.) The IRS’s rule is not an “interpretation” of Congress; it is a contradiction of Congress.

Someone who understands administrative law better than me can say whether the IRS’s “interpretation” (largely through Revenue Rulings based on Wilson) passes “Chevron Step Zero.”

Let’s see what Chevron still means in a couple of weeks when AHA v. Becerra comes out. (That’s not a prediction, just a statement that I’m not going to write a multi-page Chevron analysis when the whole thing could be void by July.)

Second, one factor of stare decisis this article hasn’t mentioned (because it wasn’t really doing a stare decisis analysis) is “reliance”: sometimes, a wrong decision should be adhered to anyway, because lots of people rely on it. There is no reliance interest in Wilson v. Commissioner and its sequelae. None. Not a single person’s ox gets gored if pregnant women get to claim a credit for their unborn kiddos.

Third, the IRS will undoubtedly point out that several congressmen over the years have tried to make the child tax credit explicitly include unborn children, and their efforts have failed. (Here’s the latest.) This effort, they will argue, shows that Congress does not believe that the child tax credit currently includes unborn children, and that the failure shows that Congress approves of that. This can be rebutted simply by naming two nouns: the equally-failed Employment Non-Discrimination Act, and Bostock v. Clayton County. As the Bostock majority wrote, “This Court has explained many times over many years that, when the meaning of the statute’s terms is plain, our job is at an end… Legislative history can never defeat unambiguous statutory text.” So too here.

Fourth, the Cassman decision openly worried about the administrative burdens of finding for the plaintiffs. While public policy arguments should not influence the judiciary (since public policy is the quintessential concern of the political branches), we all know that they do have at least a subconscious impact on nearly everyone. Let’s put our minds at ease.

While the finding that unborn children qualify for certain tax benefits may be initially disruptive, courts and states would have little difficulty adapting to the new understanding—as they have adapted to changes in law and precedent throughout American history. Initially, the IRS could require taxpayers seeking the credit to provide some reliable evidence that their fetus qualified under the statute, such as a doctor’s affidavit as to the existence of an unborn child and its age. (It could clarify the “one-half of the year” requirement in ways that are administratively bearable.) Keep in mind that the great majority of unborn children become born children and qualify for the relevant benefits anyway, so the big earthquake here will be for mothers of stillborn children, who will finally be able to get tax benefits for the resources, time, suffering, and love they invested into a person who would have been a future citizen and taxpayer. States, which currently issue certificates of live birth but are a little more slapdash about certificates of fetal death, will need to clean up their acts.

This would be a change, no doubt, but, in a country that routinely overhauls large sectors of its economy through legislation, the costs are not nearly high enough to continue holding a valid law passed by Congress in partial suspension.

Why You Still Might Lose

It seems to me that you should win this case. You deserve to win this case. As I have shown, The Law, capital-L, is on your side. If you remember way back at the beginning, the moral and practical arguments are on your side, too.

Yet there’s a good chance you’ll still lose. You’re going up against multiple precedents, one of them deeply entrenched in IRS tradition and regulations. That’s always an uphill battle. Drawing a sympathetic judge is a must. If I were to guess why you’ll lose, it’s one of these:

A court decides that Chevron deference applies after all and finds the IRS’s interpretation reasonable under the exaggerated Chevron deference of Brand X v. NCTA. I don’t see the current Supreme Court doing this, but what makes you think this is going to the Supreme Court?

Stare decisis is at its strongest when it comes to statutory interpretation. The idea is that, if a court misinterprets a statute, Congress can just fix the statute. If Congress doesn’t fix the statute, that must mean Congress agrees with the ruling. Stare decisis tends to be exactly as strong as the presiding judge wants it to be (this is why multifactor balancing tests are bad!), and no lower-court judge ever got pilloried for affirming an old precedent. Thus, it’s entirely possible the lower court just sticks its fingers in its ears and affirms Wilson, while higher courts deny your appeals.

Because I am not a lawyer, I may have made some egregious errors in this article. I don’t think that’s too likely; I finally finished reading Paul L. Caron’s analysis of Cassman after I finished writing the section above, and his analysis seems to line up pretty well with mine. (He’s less vociferous than I am, of course.) I see from Ye Olde Google that he’s a dean at Pepperdine now, so, y’know, not too shabby. Nevertheless, you should certainly talk to a real lawyer before you try and actually claim your unborn child on your taxes.

The consequences of losing this case could be substantial. If you claim an unborn child on your taxes (in knowing defiance of current IRS rulings), and you lose the case, the IRS must decide whether your case had a “realistic possibility of being sustained on its merits” in the first place. If they decide that you never had a chance, then you are considered to have “intentionally disregarded” an IRS regulation, and, under 26 USC 24 (g)(1)(B)(ii), you will not be allowed to claim the Child Tax Credit for any of your children for 2 years. With the credit currently worth $2,000 per child per year, you could easily be looking at (depending how many kids you have) taking a $6,000 or $8,000 or $10,000 hit… twice.

I like to think the pro-life community would have your back in that situation.

The Ideal Plaintiff

The process for starting this case would be straightforward:

Get pregnant in Year X.

Give birth in Year X+1.

Hire a lawyer who thinks this is a good idea.

File your taxes for Year X, claiming the child tax credit for the now-born child who was unborn in Year X.

Send the IRS a kind letter informing them of the situation and of your intent to challenge Wilson v. Commissioner and Cassman v. United States, so they don’t miss it (and then come back and audit you in a decade when they finally notice).

Wait to see if the IRS takes you to court. If they do not take you to court, tell everyone that unborn children qualify for the child tax credit now! If they do take you to court, fight and win.

However, I think the ideal plaintiff would have these characteristics:

She would have a positive pregnancy test and doctor’s confirmation of pregnancy before June 30th of Year X, with supporting evidence showing that the positive pregnancy test came before June 30th.

(Explanation: It might be possible to get around the “half the year” residency requirement for a child conceived in the second half of the year, but the easiest way forward is just to unambiguously meet the requirement by conceiving the child in the first half of the year and carrying him for the entire second half.)She would give birth to her child between January 1st and April 1st of Year X+1.

(Explanation: If born before this, there’s no case, because the IRS already awards the child tax credit in those cases. If born after, there may not be time to get a Social Security number before Tax Day.)The child would be born alive and promptly and properly registered as a live birth.

(Explanation: Although winning this case would benefit stillborn children, a stillborn child would be a legal complication.)She would apply for and receive her child’s Social Security number prior to filing her taxes by April 15th.

(Explanation: It solves some problems if the kid has a Social Security number when the credit is claimed.)She would not have traveled abroad during her pregnancy, or for at least one menstrual period before conception.

(Explanation: The child must be a “resident of the United States,” and it is easier to argue this if the child has never even arguably been a resident anywhere else.)She would have no other children at the time of the claim.

(Explanation: In the unlikely event that she both loses the case and the IRS imposes sanctions on her for “disregarding” their regulations, she will be unable to claim the child tax credit for two years. If she has only one child, that minimizes the financial risk. This is irrelevant if she has a lot of money, or is supported by a sufficiently large GoFundMe.)She would have an annual income of $400,000 or less if married filing jointly, or $200,000 or less if filing singly.

(Explanation: the child tax credit phases out above these thresholds.)She would have a federal tax liability (line 16 of Form 1040) of at least $2,000. This works out to having an annual household income around $50,000 or higher, but it varies from filer to filer.

(Explanation: The child tax credit is not fully refundable, which means you don’t get all $2,000 of the credit if you don’t owe at least $2,000 in taxes in the first place. The law about exactly how refundable it is seems to bounce around a lot. The simplest way to avoid complications, it seems to me, is to just not have to worry about refundability.)She would be married to the father of her child and filing jointly, or recently widowed, or the father of the child would be at least living together and fully supportive of the case.

(Explanation: Parents living apart can raise questions about which parent can validly claim the child tax credit, which could allow a court to escape the merits question on a technicality.)She would be represented by experienced pro-life lawyers who have fought for fetal rights before (not mere tax lawyers, who may not understand how weird judges get about treating unborn children like human beings). In a perfect world, Americans United for Life would represent her, since I think there’s none better. However, quite a few other organizations that come to mind could do the job very effectively.

(Explanation: Taking up this case with ineffective legal counsel and losing would do more damage than not taking up this case at all.)She would make her claim on or before April 15th, 2026.

(Explanation: After tax year 2025, the Trump tax cuts expire. The basic legal argument in this post would still apply, but some of the details would need to be updated.)

The End

You already have the right to claim your unborn children for the child tax credit under law, but the IRS does not recognize the law because of a really bad half-page ruling from 1940. The issue only cleanly arises under certain circumstances (roughly: your child is conceived in May/June and you can prove it), but, if that happens to apply in your case (or if you can find a way to give yourself some wiggle room) it might be a great deal of fun to prove the point in a court of law.

America’s pregnant moms would certainly thank you, and it would bring unborn children one agonizingly small step closer to full recognition under the laws of the United States. If American parents across the board begin to see fetal personhood as not just some abstraction, but as something that puts money in their pocket… well, hot dog, the way to an American taxpayer’s ballot is through his wallet. Winning this could do more to win hearts and minds than any other pro-life initiative post-Dobbs.

Imagine a stirring ending here, instead of me just collapsing in a heap at my desk at 2:37 AM. Thanks for reading.

Next time: a fresh installment of Worthy Links. After that: look, it’s Supreme Court month, who knows what will come up? In regular business, I also have a half-finished draft about an anti-gerrymandering amendment, a quarter-finished draft about Andrew Koppelman’s 13th Amendment argument, and I’ve been trying to make an essay called “The Decline and Fall of Star Trek” work for years. Or I’ll do The Orville.

As always: if you see anything that’s just wrong on this post, write me or leave a comment. Some of you out there in readerland actually are lawyers, after all! I do read everything, and I try to make proper amends when I get it wrong.

UPDATE 30 May 2023: Very belatedly, I added the “Ideal Plaintiff” section and, in the “The End” section, I added the second and third sentences of the second paragraph. I subsequently removed a passage about filing in a particular circuit because, of course, you don’t file these claims in a geographic circuit, but in an appropriate tax court. (Cassman was in the Court of Federal Claims.)

There is a common misconception you are entitled to Social Security because you “paid into” a retirement account throughout your working life, and, when you retire, that account is simply “paying out.” This is false. In fact, Social Security uses all the money you pay in to support current retirees. The money you paid in is gone. When you retire, your Social Security check will not come from your personal savings, but from the tax dollars of the younger generation that’s still working. This works as long as Americans have replacement-level fertility: 2.1 children per woman. American women today average 1.6 children.

By “fetus,” I of course include “embryo,” “zygote,” and “blastocyst.” Regardless of the medical definition, unborn children at all these stages are known colloquially as “fetuses.” It’s fine to just say “fetus.” Don’t @ me.

Just don’t use the phrase “fertilized egg” in my hearing. That phrase is an oxymoron. The egg is destroyed by the process of fertilization. It is replaced by a human child who is at the zygote stage of development.

The other main problem is that sometimes a section is cancelled out by another section—or even by a court ruling—and it isn’t obvious from the text. This is not too common, but it is very aggravating, and it does really help to have annotations.

Pro tip, though: in most sections of the U.S. Code, the important thing that covers 80% of people is in the first two or three sentences, and the rest of the section deals with exceptions, exact definitions, and procedures—which you can usually just skim.

The child tax credit has a few more conditions attached to it. It is also much harder to read. The Trump Tax Cuts Act in 2018 created temporary rules for the credit that last until 2025. (It also lowered the value of the child tax exemption to $0 for the same period.) Then, in 2021, the Biden Rescue Act modified the credit again in 2021 with even more temporary rules that counted only in 2021. In other words, the current child tax credit rules are spaghetti code. Fortunately, it mostly doesn’t make much of a difference!

The main thing that I found where a child might qualify for the exemption but fail to qualify for the credit is that 17-year-olds (and older) are ineligible for the credit, but are often eligible for the exemption. Also, the credit only pays out part of the amount if your child doesn’t have a Social Security Number before Tax Day (April 15th). This should not be a problem; the unborn children this post is mainly concerned with will generally be born and registered with SS in January/February/early March.

You can read the entire child tax credit statute at 26 USC 24, and certainly you and your lawyer should do so before you sue the IRS for your unborn child tax credit.

In the actual statute, some of this text is actually hiding down in 152(c)(2) and (c)(3), but is incorporated by reference into the main definition. I have moved it around to make it more readable. I have also omitted language that relates to students, siblings, and others who clearly aren’t relevant to our “do the unborn count?” question. If you want to trust-but-verify, I applaud that: see the original for yourself.

Unless your child is non-binary? Does a non-binary child (born or unborn) count as a “son” or “daughter” and thereby qualify for the child tax credit? 1 USC 1 says that words importing the masculine gender include the feminine as well, but that’s strictly binary, so… No, hold on, I’m not worrying about this tonight.

Here are the definitions of “child” from the Oxford English Dictionary that are clearly not relevant to our inquiry about what the tax exemption statute means. As a rule of thumb, I marked a definition “irrelevant” if any two-year-old would fail it, since we all agree that all two-year-olds can be claimed for the child tax exemption:

(b) spec. “A female infant, a baby girl. Now chiefly English regional (south-western) and Irish English.”

[Ed. The statute specified sons and daughters, and no one would read “child” in this statute to mean just daughters anyway. This specialized definition is therefore irrelevant to us.](b) “A young man; a youth, an adolescent. Obsolete (rare after 16th cent. except in biblical use).”

(c) “More generally: any man without reference to age; a lad, fellow, chap. Frequently used contemptuously or affectionately. Now Scottish regional.”“A young man of noble or gentle birth. Frequently as a title (either preceding or (in early use) following a proper name), in ballads, etc. Obsolete (archaic in later use).”

[Ed. Good luck using this definition to keep child tax credits away from the unborn by restricting child tax credits to the children of wealthy American aristocrats!](a) “A pupil at a school, esp. a charity school. Obsolete.”

(b) “spec. A boy chorister.”(a) “A person who has (or is considered to have) the character, manners, or attainments of a child, usually with negative connotations; an immature, irresponsible, or childish person.”

[Ed. The child tax benefits are not awarded to childish people generally, but to sons and daughters.]

(b) “As a form of address, used either contemptuously or affectionately.”“A young person (in early use esp. a boy or young man) in service; an attendant; a page. Cf. child-woman n. at Compounds 1b. Now only in historical contexts.”

“Scottish. Nautical. In plural. Low-ranking members of a ship's crew. Obsolete.”

“South African. In plural. Also with capital initials. Young, black, left-wing political activists during the anti-apartheid struggle of the 1970s and 1980s. Cf. comrade n. Additions. Now historical.”

(b) “The young of an animal. Now rare.”

“Esp. in biblical use: a disciple of a teacher; a person in a similar relationship to this. Usually with possessive or of. Chiefly in plural.”

“In plural. Esp. in biblical and derived uses: descendants; members of the tribe or clan.”

“A person who inherits and hands on the spiritual or moral tradition of another. Usually with possessive or of.”

“Theology. Esp. in Child of God. A person considered as belonging to God, either by creation, or by regeneration or adoption.”

“Expressing origin, association, natural relation, or characteristic: the offspring or product of a particular place, time, event, circumstance, influence, etc. (a) referring to a person. (b) referring to a thing.”

“Computing. In a tree or other hierarchical structure: a node which is immediately subordinate to another node.” Let’s give the child tax credits to a server! Or not.

“Childbirth, childbearing. Obsolete.”

This is definition 9(a) in the OED, not definition 3(a)—but HTML, the markup language that powers the Web, is surprisingly inflexible about numbered lists, so it’s showing up here as 3(a).

“Proceed from the body of another” here refers to the procession of gametes from the mother and father to form a new organism, not to the procession of the fetus from the birth canal. If it did refer to birth rather than conception, then males, who do not give birth, could not have descendants, and obviously males do have descendants.

People say pregnancy lasts 40 weeks, but that’s counting from the first day of the last menstrual period. There is no pregnancy until there’s an unborn child, and there isn’t an unborn child until dad’s sperm fertilizes mom’s egg, transforming both into a zygote. That happens within about one day of ovulation, which is typically three-ish weeks after menstruation starts.

I’m not certain you really need to have your unborn child in your tummy for a full six months of the calendar year to claim the credit. As a matter of fact, out of everything I say in this article, this is the part I’m least confident in. You might be able to argue that the IRS special rule should be re-interpreted to cover anyone who is alive, even in utero. The plaintiffs in Cassman (discussed later on) did just that. They lost, but for other reasons. Still, that special rule is kind of a big mess, and I’d rather have the plain text of the law foursquare on my side.

The extent to which Congress is allowed to delegate its legislative powers to the executive branch is currently a hot issue. Look up the nondelegation doctrine sometime to fall down a rabbit hole, and get hyped/nervous for West Virginia v. EPA, an upcoming Supreme Court decision that may signal a new era in delegation case law.

You can see §152(a)(9) in its original context on p85/pp44 of this document and what seems to be its substantively final amended version on p2/pp1607 here.

The initial ruling was Revenue Ruling 73-156, available in Internal Revenue Cumulative Bulletin 1973, Volume 1. The baby in this case was actually killed in an abortion, but survived long enough to be born momentarily and draw breath. When Sen. Jesse Helms found out that mothers were claiming a tax exemption for children they had aborted (after a rather shabby attempt, p2609, to hide this from the public), it caused a brouhaha. The “fix” for the abortion issue was Revenue Ruling 85-118, available in Cumulative Bulletin 1985, Volume 2.

If you have an appropriate subscription, you can also find the legal reasoning supporting Rev. Rul. 73-156 in General Counsel Memorandum 35124. GCM 35124 was repealed through GCM 39394, which is publicly available online, when Rev. Rul. 85-118 came out.

The Revenue Rulings are not very important in the grand scheme of things. Cassman leans on them, but only a little. However, I spent so many hours finding these documents without Westlaw access that I didn’t want to omit them from this post entirely!

IRS INFO 2004-0187, IRS INFO 2002-0291. I can’t even remember where I dug these up. Best of luck finding them.

2 of the 12 concurred only in the result.

Jonathan Cassman is now almost 30 years old and, from his social media, seems to be doing just fine. I neither know nor care about his opinion on the federal precedent that bears his name. I just have a weakness for checking on people who were once involved in court cases that they’ve probably forgotten about.

Paul L. Caron calls this, in reserved lawyerly fashion, “not particularly compelling,” and points out that this clause could just as easily bear the opposite interpretation (p5/p323).

The Board of Tax Appeals was later reconstituted as the United States Tax Court, a proper Article I court, but, in 1940, administrative law judges were still a pretty new thing, and Van Fossan’s official title was “Member,” not “Judge.” Gotta admit, I had no clue the B.T.A. ever existed until last Thursday.

Member Van Fossan, incidentally, was a Calvin Coolidge Republican who is best known for presiding over the trial of industrialist Andrew Mellon, wherein Mellon was exonerated. Mellon was the Republican who oversaw the establishment of the Board of Tax Appeals, Matt Stoller has claimed (in his book Goliath, p111) that Van Fossan and the Board tilted the trial in Mellon’s favor. That’s everything I’ve been able to find about the guy. I guess I should start his Wikipedia stub.

See the 1933 Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of “child”, the 1923 Webster’s Dictionary definition of “child”, the 1910 Black’s Legal Dictionary definition of “child”, and compare to our dictionary definitions earlier.

In 1975, the Supreme Court upheld this exclusion, partially on the basis of judicial deference to agency interpretation and partially on the basis of a peculiar legislative history… but mostly on the basis of the majority’s own personal sense (citing no authority whatsoever, much less a dictionary or law) that the “ordinary meaning” of “dependent child” means “an individual already born, with an existence separate from its mother.” Given that this was the exact same court that had decided Roe v. Wade less than two years earlier, this attitude toward unborn children is perhaps not a big shocker.

The dissent notes that the Supremes’ personal sense of what “child” meant conflicted with the decisions of five out of six circuit courts and at least ten district courts that had considered the question (although at least four district court agreed with SCOTUS). This alone shows that the Supreme Court’s vague, unsourced sense of the “ordinary meaning” of the word “child” was simply wrong.

7 Term. R. 100, 1 Bl. (Cooley's Ed.) 180, if you can read inscrutable ancient judicial cites or have a fancy-pants Westlaw subscription that can.

See part III-D of Justice Alito’s draft Dobbs opinion and its citations, on pages 58 and 59.

The Born-Alive Infants Protection Act of 2002 (codified at 1 USC 8) did define all children born alive as “persons” and as “human beings”. At first, this may seem like pretty bad news for our case! However, the BAIPA also included this clause, which absolutely prevents BAIPA from being used to support or undermine the legal status of the unborn child:

(c) Nothing in this section shall be construed to affirm, deny, expand, or contract any legal status or legal right applicable to any member of the species homo sapiens at any point prior to being “born alive” as defined in this section.

The PBABA is codified at 18 USC 1531. However, the codification lacks Congress’s bracing findings of fact. Those findings are worthwhile reminders of what so-called “bills to codify Roe”, such as the Women’s Health Protection Act, would restore to the United States. So read the PDF of the bill as-enacted.

The strongest evidence I have seen presented in a federal ruling was the fact (noted in Burns v. Alcala) that Congress considered legislation (which failed to pass) to expressly exclude unborn children from welfare benefits in 1972. This evidence, however, can be read to favor either side (as Justice Marshall points out in dissent). This is one reason courts don’t do legislative history like this anymore.

To be sure, the definition in 26 USC 152 still includes the word “individual” and presumes that a “child” is also an “individual.” However, Cassman’s holding that “individual” means “person” holds much less water under the new language, especially in light of the gloss Congress has subsequently placed on the word “child.” We could even concede that Cassman’s holding may have been correct under the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 without extending that holding to cover the different language (and different original public meaning) of the current law.