It’s Supreme Court season, and there are lots of interesting opinions coming out this week. While reading today’s interesting opinion (Moore v. Harper), it occurred to me that the way I was reading it was very different from how normal people read normal things, like books or articles. I think many lay people would like to be the kind of people who fluently read Supreme Court opinions, but they don’t know how to go about it and get stuck. They end up relying on shudder news reports, which are almost as bad as just not reading anything at all.1 Fortunately, anyone can read a court decision!

Here’s the trick. A court opinion is just like a Scholastic argument: you’re supposed to skip around.

First Stop: How They Voted

All Supreme Court opinions (and most other court opinions you might read) begin with a syllabus, which is an unofficial summary of the court’s decision. If you have no clue what the case is about, the syllabus is usually a good place to start… but, if you’re a layperson reading a court decision, you probably already have a general idea of what the case is about and who won. You can therefore skip the syllabus. (If you’re clueless, you can skim the syllabus. In no event do you need to carefully read the syllabus.)

As lay readers, our first stop is located right after the syllabus. That’s where we find the alignment summary. This paragraph explains which judges voted for the decision and which voted against. It tells us what opinions we get to look forward to in the rest of the document. The alignment summary is like a table of contents for the decision.

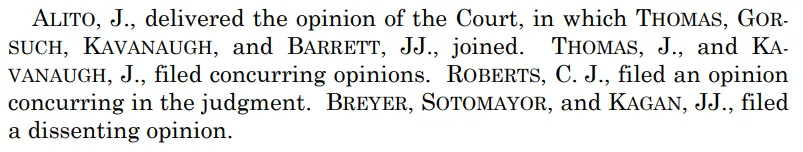

Alignment summaries are usually very simple. Most just say, “SOTOMAYOR, J., delivered the opinion for a unanimous court,” because, even today, most Supreme Court decisions are unanimous. However, in the kinds of exciting cases laypeople want to read, though, it’s often a little more exciting. Here’s one I plucked out of the archives:

In this decision, 6 justices agreed on the outcome of the case, but 3 justices disagreed. The 6 justices are the majority and the 3 justices are the dissenters.

Justice Alito, supported by 5 justices, wrote a majority opinion. Because both the outcome and the reasoning were supported by a majority of the judges in the case, Alito’s opinion became a binding precedent that all lower courts must follow.

The other 3 justices wrote a dissenting opinion. Dissenting opinions explain why the dissenters believe the majority was wrong.

Meanwhile, Justices Kavanaugh and Thomas filed concurrences. Concurrences allow individual justices in the majority to discuss issues connected to the case that the case itself (for whatever reason) did not address. Concurrences often make good reading. They’re usually short and targeted to make an impact. However, concurrences are not binding precedent.

For his part, Chief Justice (“C.J.”) Roberts agreed with the majority on the outcome in this case, but disagreed with the other 5 justices in the majority on the reasoning, so he wrote a separate opinion explaining how he would have ruled in the case. This is called “concurring in the judgment.” A concurrence-in-the-judgment is usually much longer and weightier than a regular concurrence. (They were usually first drafted as potential majority opinions, but didn’t get enough votes and became concurrences instead.) Many “concurrences in the judgment” harshly attack the majority’s reasoning, and are effectively dissenting opinions.

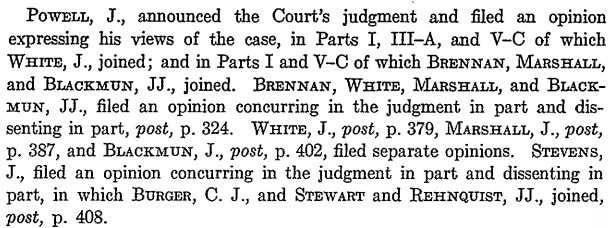

Sometimes, an alignment summary is messy, like this one:

This happens when different groups of judges agree about some parts of a case, but disagree about other parts. Sometimes this even means there is no majority of justices that agrees about both the outcome and the reasoning. When that happens, the opinion that supports the outcome on the narrowest grounds is considered the controlling opinion which binds the lower courts. The controlling opinion is always listed first in the voting summary.

For example, in the case above (The Regents v. Bakke), four justices thought the Regents should win, and four justices thought Mr. Bakke should win. The ninth justice, Justice Powell, thought the Regents should win one part, but that Mr. Bakke should win another part. That made five votes for the Regents to win the first part, and five votes for Mr. Bakke to win the second part, which settled the outcome. Justice Powell also rejected the reasoning of both blocs of justices, and came up with his own idiosyncratic argument that supported elements of both camps. In this case, Justice Powell was the only justice who supported the compromise reasoning, but, since he supported the majority outcomes on the narrowest grounds, his opinion was the only one that counted as precedent.

Everyone hates this, including the justices. Cases that turn out like this are often referred to as “fractured” decisions. A fractured decision is hard to read and often impossible to apply in later cases. The fracture shows there’s no clearly controlling underlying legal rule, and it drastically weakens how much power the case has as a precedent. Sometimes, when I see an overly-fractured alignment summary, I turn around and walk away immediately, because I know the case is going to be a slog to read, and isn’t even going to settle anything for the long run.

Now that we know what opinions are in the case, we need to get a handle on the issues in the case.

Second Stop: The Facts of the Case

The first opinion in a case is always the majority opinion, and the first thing a majority opinion does is summarize the facts of the case. That means all the stuff that happened before the case went to court. For example, in a lawsuit about whether a state can close churches during a pandemic, the majority will begin by telling the story of the church that brought the case—what specific restrictions they were under, when those restrictions went into effect, and how they believe this harmed them. The majority will also tell the story of the state—how the pandemic came about, why the state chose to impose the restrictions it did, how it made that decision, and how the state believes its people would be harmed by removing the restrictions.

Unless you are already intimately familiar with the facts of the case, this is always where you should start. Court decisions can get very abstract and are often decided on obscure technical grounds, but they always begin with a story. There are real people in that story, with profound interests at stake—and one of them is going to lose. You, as a reader, need to understand these facts before turning to the law.

That’s not because your decision should be guided by sympathy for the litigants. Far from it. All too often, the party that deserves to win, morally speaking, also deserves to lose, legally speaking. The very first duty of an impartial judge in a democratic-republican system is to make sure that the case is decided on legal, not moral, grounds. Moral grounds are for legislators, executives, and voters. Under our Constitution, judges must mechanically implement the government’s moral choices, not substitute their own moral choices.

You still need to read the facts. Partly, this is because what the law demands often turns on very specific factual details. Partly, this is because it is often impossible to understand the law without relating it to some set of concrete facts (especially for us laypeople).

The majority opinion may explain the facts of the case over the course of several pages… or it may tell the story in one paragraph and move on. It depends.

After the facts are delivered, the majority summarizes the procedural history of the case. This is the stuff that happened after the case went to court—what the original judge decided, who appealed which parts of what decisions, what the appeals court said, and how the case ultimately arrived here, on this docket. This is very important legally, because courts must always show that they actually have the authority to decide a case in the first place. The procedural history also frequently determines the specific questions the court must decide and how much the court has to defer to other bodies.

However, the procedural history is very boring, and almost never has much direct bearing on the more philosophical questions that drew your attention in the first place. Skip it for now (unless you’re engrossed). You can always come back to it later.

Third Stop: Picking an Opinion

At this point, you know who is fighting this case and what they’re fighting about (from the facts of the case at the start of the majority opinion), who won (from the syllabus), and who wrote what opinions (from the alignment summary). Now you have to decide which opinion to read first.

I usually start by making a snap judgment of the case myself, based on what little I know so far. Then I read the opinion that disagrees with my snap judgment. For example, in today’s case, Moore v. Harper, my snap judgment was that the majority opinion was correct, because I thought the Independent State Legislature theory was wrong, and the majority agreed with me. Therefore, the first opinion I looked up was Justice Thomas’s dissent. On the other hand, in last term’s Alabama Realtors v. DHS (which left the covid eviction moratorium in place for a few more months), I thought the realtors should win. The realtors lost, so I started by reading the majority opinion explaining why.

There are a couple of reasons why I seek out the opinions that disagree with me.

The first is that reading the opinion I disagree with can cast the issues in the case into sharper relief, which will help me read the other opinions more clearly and correctly.

The second reason is to save me time. After all, if my snap judgment supports the majority, and the dissent is totally unpersuasive, then I probably don’t need to read the whole majority, because I already agree with it! When this happens, I usually skip back to the syllabus, skim it, and call it quits. If I’m deeply invested in a particular area of law, or am planning to write about the case, I’ll make an exception… but, hey, I’m a layman with a hobbyist’s interest in the Supreme Court. I need to know the gist of the decision, but not every tiny detail.

The third and most important reason to seek out the disagreeable opinion is to stave off boredom. There’s nothing worse than reading a bunch of conclusions that you already agree with. There’s no challenge, and your brain gets lazy. The opinion you disagree with, however, is guaranteed to give you something to think about, both while reading it and later on, when you circle back to the opinion you do agree with.

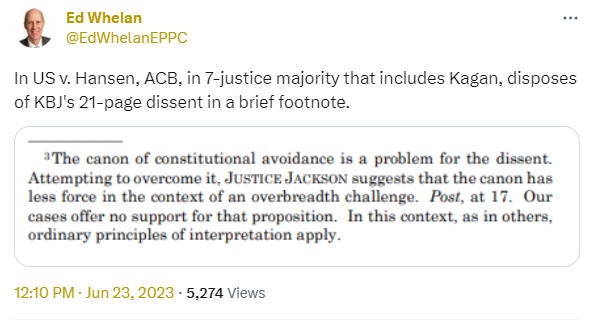

If there are multiple opinions you disagree with, I suggest starting with the one you expect to be the most persuasive. If Sotomayor and Kagan write separate opinions, both of which disagree with my snap judgment, I’m going to start with Kagan’s, because I think she’s a better writer. If Scalia disagrees with you, always read Scalia first; he was the best, clearest, most persuasive opinion writer of his generation, and everybody knew it.

If you have no idea which disagreeable opinion is going to be most persuasive, start with the shortest.

In fact, that’s a good general rule: when in doubt, read whatever’s short. If I’m staring down the barrel of a 30-page Kagan majority with a 2-page Sotomayor concurrence, it’s no sin to read the nice tasty bite-sized concurrence first.

Fourth Stop: The Merits

You’ve now picked an opinion to read.

If it’s the majority opinion, you can skip the part about the facts of the case, because you’ve already read it. You can also skip the procedural history (again).

However, you’re not done skipping yet. Many (not all) cases deal with questions of “standing”—that is, whether the person who filed the lawsuit is even legally entitled to bring the lawsuit in the first place.2 If the court finds that a plaintiff lacks standing, that’s the end of the case. As a result, if standing is contested, it’s always the first thing discussed after the procedural history.

Standing is an important issue. It was arguably developed by progressive justices in order to insulate the New Deal against judicial review by the Four Horsemen, and was (arguably) later appropriated by conservative justices in order to insulate state laws against the freewheeling policymaking of the Warren Court. However, today, the real beneficiary of standing is the presidency (regardless of party), because standing doctrine means the President can violate any law he wants without consequence as long as nobody has standing to sue him. (This is actually a pretty good summary of President Biden’s position in both last year’s eviction cases and in this year’s student loan cases: It’s illegal, but I’m going to get away with it because you can’t sue me. Remember, though, that Trump and Obama did similar things.)

However, standing is also a pretty boring, technical issue. As a judicially developed3 doctrine, standing questions hinge on the weedy details of certain recent precedents, not the stirring words of the Constitution. Standing does not get to the heart of issues that really excite people. Worse, resolving the standing question can sometimes consume half the opinion! So it’s both boring and lengthy!

At least on first reading, I usually skip the discussion of standing (and any other procedural issues). Usually (not always), any discussion of standing is covered in Part I of whatever opinion I happen to be reading, so I will skip down to Part II, where I will hopefully see something like the phrase, “Turning to the merits…” (If I don’t, onwards I skip to Part III.)

The merits of the case are the real meat, where the Court has decided that it has the authority to hear the case and that the parties have standing, and so now they can (finally) get down to the business of answering the questions presented in the case—the questions that drew me, the layperson, into the case to begin with.

Of course, if the Court determines that there is no standing in the case, that will be the end of the opinion. There won’t be a merits section to find, because the Court stops its analysis as soon as it throws the case out for lack of standing. When this happens, the Court is effectively punting all the interesting questions to some unknown future case where the parties do have standing. As a lawyer, this is often a good and necessary thing for a court to do. As a reader, it’s always a huge disappointment.

I fully expect at least one of the explosive cases this week to be settled by the Court ruling that nobody has standing. In fact, I think that’s the most likely outcome in the student loan cases.4 If that happens, should you bother reading the opinion in that case? Eh. Maybe. Probably not, though.

For example, the reason I’m interested in the affirmative action cases is because I want to know what the Supreme Court thinks the Civil Rights Act and the Equal Protection Clause mean.5 If the Court concludes that the plaintiffs lacks standing, though, they’re going to throw the case out without deciding either of those things! Affirmative action will be upheld simply by default. I’m not going to read those opinions if they’re just about standing. I don’t care enough about standing to sue schools.

On the other hand, I am interested enough in the imperial power of the presidency that I might read a standing decision in the student loan cases, but only because of how standing expands presidential power—and, yes, because I expect John Roberts to be a hypocrite about it.

Bottom line: forget standing; skip ahead to the merits.

Reading the Opinion

Now, finally, you are done skipping! You are actually beginning to read the legal opinion of a judge. This may sound difficult, but it isn’t really. Remember: the judge wants you to read this. Supreme Court judges, especially, write for a mass audience, because they want us lay people to understand the law we have to live under. They aren’t academics writing for prestige in the ivory tower. They use analogies, write with colloquialisms, and occasionally drop a zinger to keep things lively. Some of them are better at writing for laypeople than others, but all are making an effort.

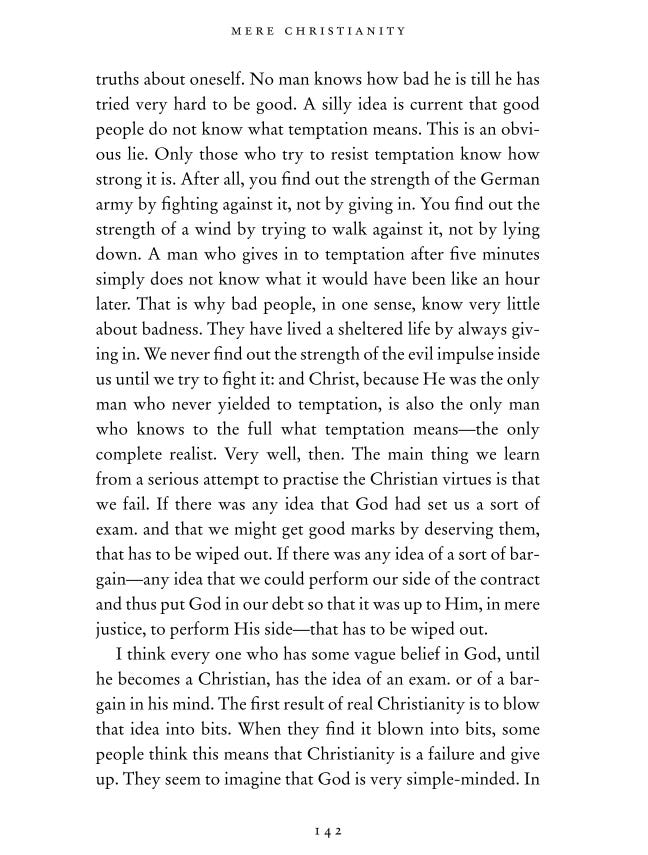

It’s also just not that many words. Here is a standard printed page of a book:

That page contains 356 words, pretty normal for a paperback. Now, here is a standard printed page of today’s court opinion… but with all the parts you can ignore crossed out:

This page is 355 words originally… but only 199 words that you actually need to read.

That’s right: nearly half of this page consists of citations (and explanations of those citations). You, the lay reader, simply don’t need to know them. You can follow them if you’re curious, but you’ll be fine without. Any precedent the opinion really needs to explain, it will explain carefully and at length. Some pages even have footnotes, which you can also ignore.6

In fact, trying to follow the citations is more likely to hinder you than help you, especially if you are a neophyte. Learning law is like learning history. When you’re well-versed in history, and you learn something new, it’s very important to know the date. The date is like a peg in a pegboard; it allows you to place the new information in the right place in your mind, and to surround it with the right context.

But when you’re a kid learning history for the first time, receiving too many dates all at once is overwhelming. You lose the thread of the story and get lost in a bunch of meaningless numbers that you can’t put together. The wise history teacher, then, focuses on teaching you one or two important dates at a time. He helps you fully understand the story, so the date sticks to your pegboard. As you learn more and more history, you need less and less hand-holding, and can take on more of it at one sitting.

Precedent is similar. There’s a bajillion precedents, and they all mean something, but trying to understand them all at once is drinking from a firehose. Understanding them will come with time, as you build up your mental pegboard of The Law and all its many facets.

Putting it All Together

Moore v. Harper was a 65-page decision that came out today. At this point, following my own method, I’ve had to read:

One paragraph on page 5 (the alignment summary),

3.5 pages of the majority opinion (Part I-A, the basic facts of the case and the early part of the procedural history, because the procedural history is kind of tangled up in the basic facts of the case)

After getting the facts, I made a snap judgment that the majority opinion was probably correct, so I went to read the 26-page dissenting opinion by Justice Thomas, which starts on page 39 of the PDF, but:

Part I of Thomas’s dissent deals with standing, so I skipped to Part II.

I read from Part II to the end, which was only 9.5 pages.

In short, I’ve read a total of 13 pages + 1 paragraph of Moore v. Harper. Accounting for the fact that half of that was citations, I’ve only truly read about 7.5 pages.

To be fair, those 7.5 pages aren’t as easy to digest as, say, the first 7.5 pages of the new novel by John Grisham. I admit, too, that I have a lot of practice at this. Still, it only took me five minutes. You, a layperson who’s never read a decision before, might take fifteen.

If I had found Justice Thomas’s dissent wholly unpersuasive, I would have stopped there. If I know that I agree with the Court based on my own knowledge of the law, and that the very best arguments the dissent could muster didn’t change my view at all, what more do I need to know? I know enough to hold a reasonably informed opinion about the case, and can engage in polite conversation about it at parties / on Reddit / with friends on Messenger.

Of course, if I were going to give a presentation about it, or blog about the case, I’d read the rest. Even then, though, I wouldn’t be reading to learn. I’d just be making certain that I hadn’t missed anything… and, well, it’s my basic professional responsibility as a blogger to read the things I rant about before posting the rant.

Alas, in Moore v. Harper, Thomas did convince me. I read his dissent shortly before I started typing this article, and now I think a narrow version of the Independent State Legislature doctrine is correct.7 My snap judgment of the case was wrong… I think.

What to Read Next

If the opinion you disagree with gives you some doubts that your snap judgment was correct—or even outright convinces you that you were wrong, as Justice Thomas just did to me—then it’s time to hear the other side. (That is, the side you originally agreed with.) If you were reading a dissenting opinion, it’s time for an opinion from the majority; if you were reading a majority opinion, grab a dissent.

It is extremely common for an open-minded, intelligent reader to change her mind about the decision at least two times while reading it. That isn’t a sign of stupidity or weakness. It’s a sign of openness. You are reading the opinions of people literally chosen for their job because of their legal genius and their argumentative prowess. It would be weird if they didn’t find a chink in your armor from time to time. Thomas found some in mine. Now the majority gets a turn, and they may very well turn me back to their side.

In Moore v. Harper, I think I probably ought to read the merits section of the majority opinion, starting with Part III. (Parts I and II of the majority opinion deal with standing.) Unfortunately, it’s 28 pages long, and, worse, it’s written by Roberts, whom I typically find unconvincing.

There’s a concurrence, though. It’s by Kavanaugh, who isn’t my favorite writer, either—but it’s short, only 3 pages. When in doubt, read whatever’s short! If Kavanaugh addresses Thomas’s points directly and convincingly, I can be all done. If not, then I’ve only spent a minute or two on Kavanaugh, and I probably still learned something interesting about the decision, which will help me as tackle the larger majority opinion.

After you’ve read everything you feel you need to read, make up your mind. This isn’t a snap judgment anymore, but an informed judgment. Still, you will often be tempted to side with the litigant you sympathize with. In Moore v. Harper, the Independent State Legislature theory is being pushed by Republicans. As a conservative, my natural sympathies lie with the Republicans. A good way to check this is to reverse the polarities of the litigants. Imagine the side you agree with is actually the bad guy. Do you still agree with their arguments? Even now, having only finished Thomas’s dissent, I’m already asking myself whether I’d still agree with his argument if it helped Democrats instead of Republicans. Sometimes I fail that hypocrisy self-check, and have to go back to the drawing board.

In the end, though, I will walk away with a pretty good handle on this case and the issues within it. My understanding will be much stronger than the understanding of someone who only learns about the case from a shudder news report. Yet I will end up having read… well, probably fewer total words than you just read in this here article!

All in all, a pretty good deal. People who write about courts are sometimes tempted (especially this week) to make it sound impressive, because then you’ll think we’re impressive… but it’s not, and we aren’t. Anyone can do it. Have fun.

UPDATE 28 June 2023: While working on this, I reread Orin Kerr’s How to Read a Legal Opinion: A Guide for New Law Students, planning to mine it for good ideas. His audience and mine are fairly different, and our approaches barely overlap, so I ended up stealing almost nothing from him. Yet that only makes his paper more valuable to my readers. If you finish this article and still find yourself feeling at sea because of terminology like “appellant” and “remand,” or still struggling to understand why American law is tied so closely to individual cases in the first place, Professor Kerr has got your back!

The exception to this is SCOTUSBlog.com, especially its reporter Amy Howe. I have written about this previously.

There are other procedural issues that can come up besides standing—like mootness, which dominates Moore v. Harper—but they, too, can be skipped. I want to emphasize standing because I think we’re getting some big standing decisions this week.

Critics would say “invented”.

Good news for me, since I would get an $8,000 refund check under Biden’s student loan forgiveness scheme; bad news for the rule of law, since, in my view, it’s blatantly illegal.

Full disclosure: my snap judgment is that I think affirmative action in college admissions is acceptable under the original public meaning of the Equal Protection Clause, but I am pretty convinced that it doesn’t matter, because the Civil Rights Act separately outlaws affirmative action in college admissions. My snap judgment would overrule The Regents v. Bakke, which linked those two laws together in a way that I think corrupts the meaning of both.

His opinion is pretty cool and collected, but his very last paragraph is fire emoji:

…On the other hand, there are bound to be exceptions. They will arise haphazardly, in the midst of quickly evolving, politically charged controversies, and the winners of federal elections may be decided by a federal court’s expedited judgment that a state court exceeded “the bounds of ordinary judicial review” in construing the state constitution. I would hesitate long before committing the Federal Judiciary to this uncertain path. And I certainly would not do so in an advisory opinion, in a moot case, where “the only function remaining to the court is that of announcing the fact and dismissing the cause.”

An interesting way of looking at things; thanks!

Myself, when I was starting to read Supreme Court opinions, I found it helpful to read old opinions from before the modern era as well - both so I could read cases where I was starting from more objective distance, and because justices from the pre-computer era usually write much shorter. But then, I would've been reading those cases for their historical value anyway; someone who isn't doing that might not find it worth it.

In addition to what you recommend reading, I've found it's usually good to at least dip into the central part of the Opinion of the Court - because even if it's not well argued as an argument, it's still the controlling opinion. So, it's going to be the starting point for the law in this area at least until the next Supreme Court opinion. For example, if you wanted to make sense of gun law from 2010-2022, reading "McDonald v. Chicago" would've been very helpful; now, you'll want to read "NY Rifle & Pistol v. Bruen" for the same reason.

(Also, I couldn't comment on your last linkspost, but thank you very much for your link to my blog and your praise!)

This is such an obviously good idea I'm slightly jealous I didn't think of it first... And so well done I don't have to do it. I can just point people here. Kudos