Readers, I’m at a bit of an impasse. I owe the paylisters something, and not just because they’ve been sitting patiently through waves of Trump coverage for three months. About six weeks ago, De Civitate’s annual revenue passed $1,000 for the first time.1 It’s all thanks to the paylisters. God bless ‘em all.

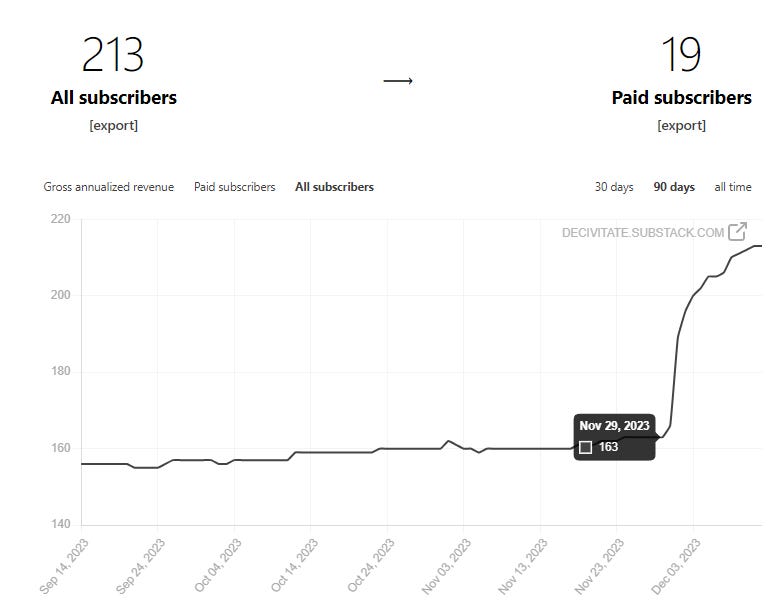

However, I owe the freelisters something, too. Somehow, I ended up included in Scott Alexander’s November Links Roundup.2 The ACX Effect was… well, see for yourself:

I can’t very well welcome all these Scott Alexander fans with a paywalled post. May God (or Uriel) bless you all, too.

So I’m writing another Short Review. These are “quick, 500-word reviews3 ” normally written for the paylist and paywalled for a few months. I started writing this article a little while ago for the paylist. However, to celebrate, I’m opening this one up to everyone immediately. Everybody wins! (?)

I could not tell you why I chose to watch Dredd one night this summer. Like everyone else, I vaguely remember this movie coming out, and that’s it. My then-fiancée, who reads comic books, told me about the trailer once. She said Dr. McCoy was in it, and this was in 2011, when there was still hope that J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek movies would bear good fruit. She told me that Judge Dredd lives in a dystopian megacity of the future where the justice system is so overtaxed that armored supercops serve as judge, jury, and executioner.

I think I said something to the effect of “If I went around sayin’ I was a judge just because some moistened bint lobbed a magic gun at me, they’d put me away!” and then we finished buying my new glasses, and then I never thought about Dredd again. Like you, I didn’t see it, my wife didn’t see it, and nobody I knew saw it. Dredd grossed $13 million domestic against a $50 million budget. Even The Marvels made twice that.4

Then, in 2023 (a few weeks before I finally replaced those same glasses) it popped up on Netflix. For unclear reasons, I clicked on it, just to see the first few minutes, just to see what a comic book bomb looked like in the days just before The Avengers changed everything.

I stayed up way too late watching it all. This is a wonderful little movie, the best comic book movie I’ve seen since, um… well, I guess since Dredd came out. (The post-2012 Spider-Man movies are also a lot of fun, but you probably recall that I had some problems with them.) The premise is simple and tautly executed: Judge Dredd and his failing trainee Cassandra are on the ground floor of a 200-story slum (population 70,000). Up in the penthouse, sadistic drug queen Ma-Ma Madrigal locks down the building, trapping everyone inside, then dispatches her entire gang to eliminate the two judges. Dredd and Cassandra must battle their way up to the top of the building to confront Ma-Ma, while keeping a witness alive.

Rotten Tomatoes tells me that Dredd got a lot of props at the time for its “slick action” (top review: “If Hollywood is going to be indicted for making mindlessly violent action films, let them at least be as good as this one.”) I disagree. Action for its own sake is no fun. It’s just choreography. I stopped watching Netflix’s Daredevil because so much of the show was just watching two actors stylistically punch one other. I kept getting bored waiting for the actors to finish so I could find out what happened to their characters. Watching action that doesn’t reveal character is just like watching that interminable dance scene at the end of The Gay Divorcee.

Dredd does have quite a lot of action, but rarely for its own sake, never forgetting its characters. The blood and gore, highly praised in several reviews, is both completely unnecessary and (by 2023 standards) very fake-looking. If you can look past that, though, there’s a neat little movie about two people trying to do right in a place where right isn’t an option. Characters are driven by their choices, and even the implacable Dredd has a (subtle) arc.

However, I don’t want to talk about that. I want to talk about the rule of law.

If you know only one thing about Judge Dredd—as I did before seeing this movie—it’s his catchphrase, “I AM THE LAW.” When my fiancée told me this at LensCrafters, I took the catchphrase as a statement of hubris, like King Louis XIV’s “L’etat, c’est moi” (“I am the state”), an assertion of authority to do as he sees fit.

That’s the rule of men, a mockery of the rule of law. If the rule of law means anything, it is that conduct is judged based on freestanding, pre-determined rules, not the unbounded discretion of a capricious lord and his hourly whims. I wasn’t interested in watching a lawless executioner roam the countryside punishing any behavior he happened to dislike. It reminded me too much of Anthony Kennedy.

I was wrong. That isn’t how Judge Dredd understands himself. This is clear from his speech:

Inhabitants of Peach Trees, this is Judge Dredd.

In case you people have forgotten, this block operates under the same rules as the rest of the city. Ma-Ma is not the law.

I am the law.

Ma-Ma is a common criminal. Guilty of murder, guilty of the manufacture and distribution of the narcotic known as Slo-Mo, and, as of now, under sentence of death. Any who obstruct me in carrying out my duty will be treated as an accessory to her crimes.

You have been warned.

And as for you, Ma-Ma... judgment time.

Dredd doesn’t see himself as the origin of law, like King Louis or Justice Kennedy. Dredd sees himself as an avatar of the law.

He very much believes that the law is a freestanding set of pre-determined rules, which it is simply his duty to apply. In fact, he is scrupulous about them, instantly dispensing sentences according to the statute books of Megacity One, which he has apparently memorized. Vagrancy: three weeks in an isocube. Narcotics possession: two years. Neither merciful nor vengeful, he does neither more nor less than the law demands.5

Presented with very strong (psychic) evidence that the perp they’ve just apprehended also committed three brutal murder-tortures, Dredd doesn’t doubt it for an instant… but his equally instant response is, “Can’t execute a perp on ninety-nine percent.” He spends most of the rest of the movie attempting to keep this scumbag alive and in custody, despite the impossible circumstances, even when Cassandra suggests cutting him loose (or, she says without words, maybe we should just execute him?). Dredd doesn’t even dignify it with a response.

Dredd is not usurping the law, like Louis and Kennedy. Dredd has made himself the law’s slave. She has subsumed him so completely that he has, in a sense, become her. This is kind of beautiful.

His little speech has a big problem, though:

Queen Ma-Ma

[T]his block operates under the same rules as the rest of the city. Ma-Ma is not the law.

No, it doesn’t. Yes, she is.

A rule is not generally considered a law unless it meets certain criteria: it must issue from the lawgiver, often understood as an authority with a monopoly on violence. It must be publicly promulgated, so that those subject to it know what rules of conduct they’re expected to abide by. It must be general, applying equally to everyone subject to it. It must be predetermined and prospective, punishing only conduct that occurs after the rule is formulated. It must be clear and determinate, so that enforcers cannot simply use a vague law to punish conduct they happen to dislike on the spot.

The rules of the Ma-Ma Clan meet these criteria.

Peach Trees is just one building, but it has the population of a small country. Within this country, Ma-Ma Clan has crushed all opposition and holds an unquestioned monopoly on violence. After Judge Dredd arrives and challenges her, even residents sympathetic to Dredd agree that Ma-Ma controls this little nation, and is highly likely to continue doing so:

MEDIC: This is a medical facility. Neutral ground.

DREDD: You’re not neutral. You’re choosing sides.

MEDIC: Peach Trees has been sealed by blast doors designed to withstand nuclear attack. No one is getting out. No one is getting in. And you have every Clan affiliate in the block after your blood. You’re already dead. There are no sides.

If the monopoly on violence is how we identify local legal authority, Ma-Ma has it.

The laws Ma-Ma Clan promulgates are very clear and appear to be well-understood by every resident. To be sure, these are not laws that the peasants of Peach Tree are likely fond of. Examples include, “Do not deal drugs for rival gangs; violators will be flayed,” and, of course, the ever-popular “Do not interfere with the sale of drugs by authorized agents of the Ma-Ma Clan; violators will be flayed.” But peasants never have much love for laws that burden their commerce, and it is eminently within the power of government to award commercial monopolies to favored subjects. That’s all Ma-Ma has done through these laws.

Moreover, they appear to be general laws applied equally to everyone in Peach Trees, from the lowliest child to the most trusted lieutenant of the regime. Ma-Ma herself, as sovereign, likely has immunity to them while she holds office, but this is not so uncommon; even the President of the United States is immune to most prosecutions while in office.

Moreover, when Ma-Ma makes new laws, she promulgates them clearly, so that every resident has notice of their new obligations to her civil administration:

Peach Trees. This is Ma-Ma. Somewhere in this block are two judges. I want them dead. And until I get what I want, the block is locked down. All Clan, every level, hunt the judges down. Everyone else, clear the corridors and stay the fuck out of our way until the shooting stops. If I hear about anyone helping the judges, I'll kill them and the next generation of their family.

This decree prescribes two simple, clear rules of conduct, defines their applicability, and attaches penalties to violators as a deterrent. (She also sentences the judges to death for a clear violation of Peach Trees law.) The rules are prospective; no one is punished for having helped the judges prior to this moment. If you start from the ordinary assumption that the Peach Trees regime is entitled to advance its longstanding state policy, these rules rationally follow from those objectives. This is legislation.

True, Ma-Ma’s regime doesn’t spend much time on technical legal process, like trials and juries… but, then, neither does Mr. Dredd’s.

Ma-Ma is the law here. Dredd does not come as an agent of the government. He comes as a foreign invader. Like most foreign invaders, from King Edward III to Vladimir Putin, Dredd brings with him an ancient claim of legitimacy that was, for all practical purposes, abandoned to the current regime ages ago. Dredd has come to seize Peach Trees by conquest.6

Judge Dredd, the Absurd Hero of MoralIntern

I think that’s where a progressive critic of Dredd might stop. Mr. Dredd is, at worst, an usurper out to destroy the simple folkways of Peach Trees and oppress its impoverished natives with a colonizing7 code of law that privileges powerful outsiders. Those attempting to destroy Dredd are not criminals, but heroic resistance fighters against a cruel and unfeeling invader.

At best, this sort of progressive critic might grant that Judge Dredd is no worse than Ma-Ma, but maintain the he is no better than her, either. He’s just the tails to her heads. Both are out to project their power, neither is accountable, neither even pretends to follow Anglo-American principles of “due process of law” with trial by jury and so forth, and civilians are constantly caught in their crossfire. Dredd even executes Ma-Ma the very same way she executed the rival drug dealers in the beginning, making the circle complete! (I think this is what the New York Times’ abbreviated review was driving at, but it was so brief I wasn’t sure.)

It’s plausible that this is as far as you can get on purely formalist accounts of the law. I even think it’s plausible that this was, in fact, what the filmmakers were trying to convey. As always, in any movie written by a reasonably intelligent person, you should look to the villains’ monologue to see what the author believes (or fears) is true:

DREDD: [A million credits] doesn’t sound like much. To betray the law. Betray the city.

LEX: Save that shit for the rookies. Twenty years I’ve been on the street. You know what Megacity One is, Dredd? It’s a meat grinder. People go in one end. Meat comes out the other. All we do is turn the handle.

Yet, to us in the audience, that isn’t the whole truth, is it? The vast majority of us see a clear difference between Dredd and Ma-Ma, and we cheer for Dredd. Why is that?

Dreddful Virtues

The progressive critic might say that our sympathy for Dredd only proves our complacency and complicity in the systems of oppression Dredd represents. I suppose that’s conceivable, but, before confessing ourselves cogs in the kyriarchy’s machine, let’s see whether we can find anything that really does distinguish Dredd from Ma-Ma.

First, Judge Dredd’s claim to legitimacy is not just talk. Peach Trees was once under the law of Megacity One’s Hall of Justice, and Ma-Ma never formally seceded. Moreover, Ma-Ma’s monopoly on violence is much more fragile than it looks. The reason Ma-Ma seals the building is precisely because she knows she would be crushed in any direct confrontation with the Hall of Justice. She has to dispose of Dredd without arousing suspicion, evading her enemies’ fickle attention. She operates Peach Trees like a scrappy third-world dictatorship in the shadow of a Cold War superpower. Dredd, in this light, is less like an invader and more like a rival claimant.

However, this vestige of legitimacy doesn’t buy Dredd anything practical. I’m usually wailing about legitimacy conflicts because they divide the public, leading to instability and civil war. Dredd carries a claim of competing legitimacy into Peach Trees and it causes zero division, because nobody recognizes it. Once Ma-Ma issues her decree, not a single resident of the towers helps Judge Dredd, except out of pure and explicit self-interest. None of them loves Ma-Ma, but they all recognize her law over Dredd’s rival claim. I doubt that we in the audience are cheering for Dredd only because we never see Ma-Ma issue a formal declaration of independence.

A second possible difference is that Ma-Ma’s law is autocratic. Megacity One is in the West, so Judge Dredd’s law, at least presumptively, has democratic roots. In the 21st century, we reflexively love democracy and hate autocracy so hard that maybe we’ll always support democratic oppression over monarchical oppression. Thus, we cheer for Dredd. However, I’m not confident this explains it. The movie does not make the governing system of Megacity One explicit, but suffice to say that heavily armed judges rolling around on motorbikes executing criminals on the spot do not send big “healthy democracy” vibes. The logo on the Hall of Justice looks like something Mussolini would have stenciled on his luggage. If we’re cheering for Judge Dredd, it probably isn’t because he’s a duly-elected representative of the People. I doubt8 he secured his Judgeship in a non-partisan election with an endorsement from the Megacity One Bar Association.

A third potential difference is that Megacity One may in fact have limited due process of law, whereas Ma-Ma clearly does not. We see three criminal records in the opening scene, which shows perps having some sort of trial or hearing process; receiving parole, probation, and sentence-reduction; and enjoying the right to an appeal. However, this is clearly not something an Englishman raised under the Magna Carta would call “due process of law.” It is unclear that cases ever reach trial or that appeals are ever successful, there is no sign of legal representation or jury trial, and nobody gets read their rights. Whether its Judge Dredd or Queen Ma-Ma pronouncing guilt and giving sentence, both systems seem about equally free of criminal protections.

Finally, a fourth possible difference is that the law Dredd is trying to enforce seems fundamentally different from Ma-Ma’s.

Ma-Ma is a sovereign in the Hobbesian sense: she operates beyond moral values, ensuring a kind of security and stability for the commonwealth of Peach Trees by common consent. Residents obey her out of fear. They fear Ma-Ma will hurt them. I think they also fear the anarchy that might follow if Ma-Ma ever fell.

Nevertheless, Ma-Ma’s laws serve Ma-Ma’s interests first, her gang’s second, and everyone else only by accident. She accomplishes her sovereign goals by any means necessary. Her subjects know this, and that’s the law of Peach Trees, but that’s little comfort when, in an attempt to take out Dredd, Ma-Ma uses miniguns to massacre an entire floor—scores if not hundreds of men, women, and children. To be clear, this attack is not inherently illegitimate! At times, every ruler faces the choice between accomplishing a key objective or avoiding collateral damage. The Allies could not have stopped the Nazis without at least some bombing of Nazi industrial centers, which was bound to cause civilian casualties. Yet Ma-Ma shows no concern for the casualties whatsoever. She simply values her interests over those of her subjects, and legislates accordingly.

Dredd’s law, by contrast, is animated by other concerns. The Hall of Justice is principally concerned with homicide, riot, armed robbery, assault, rape, “deviancy,” and drugs:9

These are crimes that harm persons, and which disproportionately harm a particular kind of person: innocent persons.

Ma-Ma’s law has no concept of innocence. It is irrelevant to her. To Ma-Ma, there is only the goals of the State and the most efficient means that might bring them about. If that means some people who haven’t broken any of her laws have to die, so be it. Indeed, Ma-Ma sometimes uses threats of violence against innocent family members to ensure compliance from her agents. She certainly doesn’t seem to lift a finger to better the lives of innocents except insofar as it serves her own interests. If forced to define “innocent,” Ma-Ma (or her lawyer) would likely describe an innocent, within her system, as “someone who isn’t currently impeding my goals.”

Dredd’s law, by contrast, is built around the innocent. In the opening car chase, Dredd upgrades an arrest to an execution when the criminals kill an innocent bystander. He then offers to downgrade “execution” to “life without parole in exchange” for the release of an innocent bystander who has been taken hostage. Whatever you think of Dredd’s negotiating tactics (they are not super-effective) and rules of engagement (he tolerates far more civilian danger than our own police would), this nevertheless suggests that Dredd’s law is especially concerned with the lives of the innocent. Indeed, Dredd’s insistence on keeping a prisoner alive, at great personal danger, even though he is “99%” sure that the prisoner committed capital crimes, shows that his law insists on a presumption of innocence as well as protection of innocents.

These are not natural characteristics for a law to have. Collective punishment, indiscriminate force, the presumption of guilt, and so on are largely foreign to us, but, historically speaking, they’re pretty common features of different systems of law. A law that eschews them is a little bit weird!

Dredd is committed to his weird law. When he discovers that some Judges have become corrupt, Dredd is livid, not because their defection threatens the State (although it does!), but because it threatens innocents. He describes this as “betraying the law.” I am not here to argue that Judge Dredd or the system he cares about are very good at protecting innocents. Even Trainee Cassandra sees, by the end, that the judges’ system isn’t working as promised. I am only arguing that Dredd represents a law that thinks protecting the innocent matters. Ma-Ma doesn’t.

It seems, then, that Dredd doesn’t perceive the law in Hobbesian terms. Judge Dredd believes that there is an objective rule of justice. This rule pre-exists the positive law established by individual sovereigns, like Ma-Ma and his own Hall. This rule of justice, whatever else it contains, doesn’t simply instruct that innocents are not to be harmed; Dredd seems to derive the very definitions of “innocent” and “guilty” from this rule of justice, rather than from the written laws of Megacity One.

I propose that the law Judge Dredd has enslaved himself to is not the statute book of Megacity One. He is, instead, a devoted servant of this higher “rule of justice.” Dredd honors the statute book of Megacity One only insofar as those statutes reflect and participate in the higher rule. When Dredd announces, “I AM THE LAW,” he isn’t claiming that he has a local monopoly on violence or appealing to the legitimacy of bills passed by some off-screen legislature. He is announcing his fealty to the universal rule of justice, and observing that Ma-Ma is outside of it. This isn’t Hobbes’s law of nature, but Thomas Aquinas’s natural law. In this view, laws are indeed freestanding, predetermined rules of conduct, but they aren’t predetermined entirely or even primarily by any individual human or group of humans. They are predetermined first and foremost by objective facts about human nature, and so “freestanding” that no human force can ever overthrow them. Ultimately, Ma-Ma must be taken down not because she is a criminal, but because she is a villain.

I propose that we cheer for Dredd because, deep down, we agree.

It would be dangerous to take too much away from this. We are not entitled to overthrow local government by force of arms, Dredd-style, every time our local government fails to participate perfectly in the natural law. Most of us will have pretty stiff disagreements about what that law even entails, and most of those disputes are best resolved by discussion and voting, not armor-piercing rounds.

Nevertheless, I do think the validity of written law is ultimately rooted in something higher than the written law itself, higher even than the subjective collective impulses of some teeming mass of voters. I’m not sure how we could maintain belief in an objective ideal of protecting the innocent without it.

It is easy to lose sight of this in modern times. Partly, this is because our law aligns so well with the objective rule of justice in so many cases that it’s hard to see a difference between “criminal” and “villainous.” Largely, I think this is because our society has lost the capacity to discuss morality.

Of course, people angrily assert objective moral rules all the time. Indeed, every substantive law, from homicide law to sex laws to tax laws to traffic laws, are based on a moral assertion. The saying is that “you can’t legislate morality,” but the reality is that you can’t legislate anything else, and anyone who says otherwise is trying to sneak a morality past your sensors.10 However, because we no longer have a shared social basis for making moral assertions, and we have come to consider all assertions of objective religious or metaphysical truth inherently suspicious, all we can do is angrily assert our subjectively objective moral rules and then shout at each other about them.

So we avoid that! Instead of arguing about what the universal rule of justice entails, we argue about what the positive law says. We cite the Constitution or the Universal Declaration because we no longer have the resources to have a conversation about why the Constitution and the Universal Declaration are true. I myself do that all the time. Much of this blog is spent buried in questions of legal propriety rather than objective morality.

I like Dredd for making that impossible. It strips away every excuse to talk about other elements of legal validity and reminds us of the truth at the law’s core: all law must be grounded in objective truths about human nature, or it isn’t really a law at all.

So Ma-Ma really is not the law. Judge Dredd is the law.

Nice.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to see more articles like it, remember that Short Reviews are usually paywalled, so now’s your big chance to upgrade your subscription! If you thought it was rubbish, uh, probably don’t subscribe!

With so many new subscribers, I am really interested about hearing what you guys actually want to read (are you all Catholics? E.A.’s? Both?), so feel free to introduce yourself and your interests in the comments!

A month later, it went back down to $928, but I still hit the milestone and it still feels great.

Oddly enough, the thing I was reading at the moment my traffic alerts started blowing up was… an archived copy of Scott Alexander’s incomplete book review of Ed Feser’s The Last Superstition, from his old now-deleted LiveJournal (Part I, Part II). Having just finished The Last Superstition myself (prep for the next installment of Letters to a Growing Catholic). So I was, in fact, giggling away at Scott Alexander when Scott Alexander linked me. Small blogosphere!

Of the two 500-word Short Reviews I have written, this one is the shortest, at only 4,000 words. My next Short Review is probably Heroes of the Fourth Turning, and that promises to be a doozy.

More like 1.56 times if you adjust for inflation.

Because the movie is so clear about Dredd’s refusal to bend in any direction, most of the interesting moments in Dredd’s come when he does bend—in two cases toward vengeance, in one toward mercy, and in one toward prudence. Since those moments aren’t relevant to the point I’m trying to make, though, I’ll leave them unspoiled.

JAMES’ ID: Ooo! Ooo! Call him a colonizer! Call Judge Dredd a white male Peach Trees colonizer!

JAMES’ BETTER JUDGMENT: No.

JAMES’ BETTER JUDGMENT: Dammit!

The comics probably clarify this, but I have never read a Judge Dredd comic.

True, the Hall of Justice is also concerned with “subversion,” but all regimes are concerned with subversion. Some are better at tolerating it than others, but, if you don’t think your regime works to suppress subversion, it just means power in your regime doesn’t reside where you think it does.

Because I just happened to be reading it while bringing in the groceries a few minutes ago, I give you, as an example, James Bennett’s essay on the New York Times’ increasingly strident attempts to tamp down on subversive ideas. Many such cases.

The Hall of Justice is clearly both more open about this suppression and likely much more forceful about it. To be clear, I think that’s very bad. All I’m saying is that every government, whether monarchical or democratical, must in some way, to some extent, defend itself against attempts to destroy that same government, so it’s not inherently illegitimate to see the Hall of Justice government doing this.

Or censors.

I'm a conservative protestant who is very sympathetic to my fellow catholic believers. I found you from Scott and have very much enjoyed your Trump, Synod, and Minnesota takes. This essay though is spectacular, I'll have to subscribe once I'm more employed.

Congrats on those first few paragraphs! If I’m remembering you last exclusive-to-the-old-blog post your aspirational goal was to make writing your day job but your initial goal was to just make enough in subscriptions to offset the cost of your next PC… at this rate you’ll be buying a few PCs a year just to keep your costs up with revenue!