Spider-Man: No Way Out

The latest Spider-Man is a decadent, morally empty work of zombie art... so, just another Tuesday in Hollywood.

Spider-Man is my favorite superhero. He’s fun, he’s relatable, and the stakes of his adventures are human—rarely “the fate of the world,” more often, “the fate of this one crowded schoolbus and also my best friend.” I have seen every Spider-Man movie in theatres, including the Kurtzman/Orci farrago that dared call itself Amazing Spider-Man 2: Rise of Electro. I played a rental copy of Spider-Man 2 to death on Gamecube years before everyone realized it was the greatest Spider-Man game ever made, and I still own my disk for the far inferior Spider-Man 1 on Sega Dreamcast. I’m not a true fan—I have never read The Clone Saga, or really any of the comics—but I only saw two movies in theatres in 2022, and one of them was Spider-Man: No Way Home.

I loved it. Of course I loved it. Everyone loved it. No Way Home earned nearly a billion dollars domestic, more than all previous Spider-Men, even Sam Raimi’s 2002 original—even after adjusting for inflation, even after excluding today’s much larger international market, even if you pretend that No Way Home didn’t release into the teeth of a pandemic that depressed box office receipts the world over. The only Spider-Man more beloved by critics is Into the Spider-Verse, because critics are massive suckers for gorgeous animation and always fall for it. After five long years of blockbusters turning into bizarrely politicized litmus tests—Ghostbusters,1 The Last Jedi,2 The Rise of Skywalker,3 Star Trek Discovery,4 The Rings of Power,5 The Eternals somehow,6 the Disney live-action remakes,7 etc.—left-wing clickbait critics and right-wing clickbait YouTubers joined hands and loved No Way Home together. Of course I loved it.

It was only in the car on the way home that I started to think about it, and began to realize, “…I don’t feel so good.” By the time I got home, I was ready to write my Letterboxd review:

I occasionally mentioned here on De Civ that No Way Home Was Bad, Actually.

…Okay, I admit, I didn’t just say it was bad. I called No Way Home a “decadent, morally empty work of zombie art.” It is not surprising that this caused an outcry. This is, presumably, how Armond White gets clicks.

To be clear: I am not pulling an Armond White. I did not seek out a high-rated movie to dump on for contrarian bonus points. As you can see from the footnotes thus far, my movie opinions are conventional, even banal. I just think there’s something really wrong at the heart of No Way Home.

This month,8 while developing my case, I rewatched not only No Way Home, but all nine Spiders-Man:

the Sam Raimi/Tobey Maguire trilogy,

the aborted Orci/Kurtzman/Andrew Garfield duology,

the Marvel/Tom Holland trilogy, and

the standalone animated film, Into the Spider-Verse.

That’s 1,192 minutes of Spider-Man.

I also watched Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness for the first time, because No Way Home shares a tangled production history with it (plus, it’s a Sam Raimi movie). I also reviewed most of Infinity War, five minutes of Civil War, and the end of Endgame, because Marvel does not hesitate to put really important Spider-Man character moments in non-Spider-Man movies.

So that’s… [does some figures]… 24 hours or so, with detours, all before I could even start typing this beast. I have a wife and kids. It took me a year to watch the last six episodes of The Expanse. The things I do for you, dear subscribers!9

Spider-Man: No Way Home has three central problems: decadence, futility, and determinism. All three are common in modern film, because they are the basis of Consensus Western Metaphysics, but, in No Way Home, they assemble like the Power Rangers. Combined, they form one overall problem: a dark, yawning nihilism that threatens to consume everything you love.

But, hey, nice to see Tobey again!

Decadence

Our society is decaying. It is trapped in a cycle of repetition and stagnation, reviving the same questions and coming up with the same answers over, and over, and over again. We are affluent without growth or purpose. We see this all over our society, from our wage paralysis to our political sclerosis to our growing mental health crisis. Unsurprisingly, we see it in our art, too.

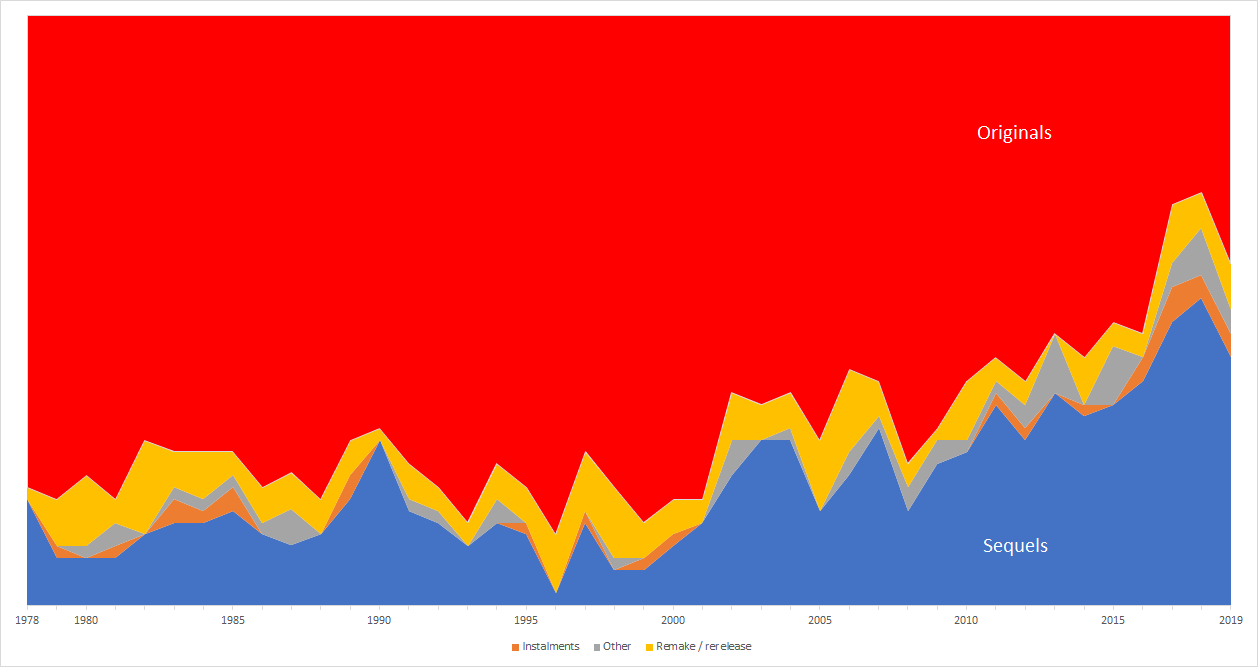

The problem is not simply that we are making less and less “original IP” and more and more reboots, recyclings, and franchises. It’s true that we are doing that,10 but it’s only a symptom of our larger problem. The very idea of “original IP” is ugly and inhuman, born surprisingly recently of wholly artificial corpo-legal power. Much of human literary history has involved various authors “rebooting” and “franchising” things like Greek Mythology and King Arthur. However, our dependence on reboots is accompanied by a growing dependence on regurgitating the same setpieces, the same styles, the same lines, the same ideas, over and over again.

Unlike the collapse of “original IP,” the collapse of original thinking is very hard to prove with metrics. You have to go out and see it. But I’ll at least try to explain what I mean.

Take the Star Wars franchise. Star Wars was invented in the old American melting-pot tradition: take some empty-headed Buck Rogers serials, toss in some Akira Kurosawa, season liberally with 1950s Western flavors, pour into the 120-minute blockbuster pan perfected by Jaws, and ding! You’ve made something entirely out of old parts, which is nevertheless entirely new, the way a child is made of his parents’ genes yet is entirely different from both of them. No one should call the first Star Wars profound cinema, but it’s healthy cinema. On each viewing, I admire the hundreds of smart little narrative choices it makes all the more. I wasn’t around for its release, but I’ve seen it many times (especially now that I have kids).

I was around twenty years ago, when George Lucas made the Star Wars “prequel trilogy.” In fact, Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones came out the same year as Sam Raimi’s original Spider-Man, which makes it a useful point of departure for us.

Attack of the Clones is quite a bad movie, easily the worst of George Lucas’s six Star Wars. It’s impossible to defend dialogue like…

I don't like sand. It's coarse and rough and irritating and it gets everywhere. Not like here. Here everything is soft and smooth.

…spoken by Anakin Skywalker while he extremely creepily caresses Padmé Amidala’s arms. This set off alarm bells in every viewer from here to Ord Mantell but apparently turned Padmé on. (Reader, she marries him!) This is only the beginning of Attack of the Clones’ laundry list of cinematic sins.

But Clones—like everything else in the prequel trilogy—was also a bold attempt at doing a lot of things that Star Wars had never done before. In fact, we know that George Lucas wasn’t really thinking about what Star Wars had never done before; that’s the kind of thing only a rot-brained decadent from the 2020s would think about. Lucas was (watch the prequel trilogy DVD special features if you don’t believe me) trying to do things that cinema had never done before. He was trying to portray the fall of the Roman Republic in a sci-fi action trilogy with mystical space monks and epic laser battles, with a central character whose slow road to corruption, one ugly choice at a time, mirrors the slow corruption of the world around him. All this had to be done within the confines of a pre-existing legendarium, which provided both creative constraints and emotional heft. His prequels had to be enough like the originals to justify their existence within the shared universe, but different enough to artistically justify making them at all. This was a hugely ambitious project. Even if the prequels had been completely successful, they would have required viewers to expand their palate, to grow toward the prequels. So the prequel trilogy wasn't decadent. It was just bad.11

Now jump forward a couple of decades into our more decadent present. J.J. Abrams made a Star Wars movie called The Force Awakens. It was devoid of creative ambition. To call it a remake of the original Star Wars, or even a lame pastiche of it, is actually to understate the problem, because Abrams did not stop at mechanically regurgitating a plot he knew audiences had lapped up forty years earlier. He added layer after layer of what the satirists at South Park dubbed “memberberries”:

A memberberry is not a mere callback, but an ostentatious attempt to play on your nostalgia. As Erin Horáková put it in her landmark essay, a memberberry “gamifies continuity, trading the sense of a stable world necessary for the development of emotional and thematic through-lines for a facile ‘spot-the-reference’ game intended to glut media consumers with smug… self-satisfaction.” When a Star Trek project wedges in Robert April and then pauses for a beat for the audience appreciation moment, or recreates an entire sequence from a beloved previous film; when an Indiana Jones movie gets Indie to say “Snakes… why’d it have to be snakes?”; when a Top Gun movie wedges in a worshipful Val Kilmer scene that is just confusing to anyone who hasn’t seen the original movie: these are memberberries. Memberberries are like nutmeg: they are delicious, and can enhance a film in small quantities, but more than a couple teaspoons are poisonous.

The Force Awakens leans on the previous films like a crutch, unable to tell its own story… while you, the viewer, are lulled into a nostalgic stupor. The pleasurable tingles shooting down your spine aren’t the excitement of exploration, of art; they become inward-facing, empty twinges that feel remarkably similar to masturbation.

Masturbation—the fruitless stimulation of pleasure to no productive “growth or purpose”—is the default condition of a decadent society. It’s very easy to take any movie J.J. Abrams has made since 2006 and hold it up as an exemplar of decadence.

This is not a very interesting take. Everyone agrees The Force Awakens is nostalgic puke.

I’m far more interested in Rian Johnson’s sequel.

The Last Jedi is a controversial movie. It is held up today, by both its fans and its haters, as an ambitious attempt to subvert the “rote” Star Wars formula and do something “new.” Fans and haters then yell at each other ad infinitum about whether it is bad for Star Wars to reinvent itself, and, if so, whether Rian Johnson’s reinvention went in the right direction).

I think this is bizarre. The Last Jedi is not a reinvention. It is very obviously less original, less interested in pushing the boundaries of filmic stories, more enslaved to the original trilogy’s cinematic vocabulary—and far, far more dependent on memberberries—than George Lucas could have even imagined when he was making Attack of the Clones.

The Last Jedi wasn’t actually ambitious. It was only somewhat less flamboyantly unambitious than The Force Awakens, or The Avengers, or Jurassic World, or Furious 7, or Disney’s almost word-for-word live action remake of Beauty and the Beast. If the charge is ambitiously rewriting the Star Wars formula, George Lucas is guilty a thousand times more than Rian Johnson… and yet, at the time he made the prequels, this critique was barely on the radar. If anything, Attack of the Clones was critically razed for not being ambitious enough. (Also, for being bad, which is sadly undeniable.)

The intense, lasting backlash against The Last Jedi’s very tepid ambition tells us something important: we, the audience, aren’t consuming the same stories over and over and over again because writers are creatively bankrupt or Hollywood is risk-averse. We’re eating our own excrement because that’s what we want.

This is bad. Art should take us out of ourselves, to new places and perspectives, to a richer understanding of what it means to be a thinking animal in a confusing cosmos. Art should entertain, certainly, but it should also teach us a little about being human along the way. Every great work of art you admire and love has done this—and that is, in large part, why you love that art.

This includes blockbusters for the hoi polloi. Indeed, mass media is more important than arthouse films. Babette’s Feast may be a wonderful movie (fact check: true), but its ideas about right and wrong, good and evil, choice and consequence will have exactly zero effect on the moral understanding of everyday Americans, because like nine people have ever seen Babette's Feast. Meanwhile, Spider-Man: No Way Home sold… (does some math)… about 84,000,000 tickets in the United States alone, and that’s before we talk about its 2022 re-release or its DVD sales or its streaming run. Blockbusters are the movies that shape our culture. When they decay, we decay (and vice versa).

So when blockbusters become (even moreso than usual) repetitive, trite, and formulaic; when they seem to offer no path forward, nowhere to go but backward for another memberberry feast; and when we ourselves seem to demand this… then it is not terribly surprising that everything else in our culture feels the same way—especially our politics. Today, our politics is the shambling corpse of ‘80s Reaganism doing battle with the shambling corpse of Pat Buchanan’s ‘90s national conservatism on the one hand, and against the shambling corpse of late ‘60s social justice radicalism on the other.

Incidentally, the first-place movie of 2022 (Top Gun: Maverick) was ‘80s nostalgia, the fifth-place movie (Jurassic World) was ‘90s nostalgia, and the second-place movie (Black Panther: Wakanda Forever) is based on a comic book character created in the late ‘60s as a literal social justice warrior. Which brings me, at long last, to Spider-Man.

“Franchise” is a word for corpos, not humans; it refers to money and property, not creation or joy. Hearing it applied to movies should always send a shiver down your spine. Spider-Man is not a film franchise.

It’s three.12

In the beginning, there was Sam Raimi’s trilogy (starring Tobey Maguire), and it was good. Raimi’s movies were based on a comic book character, but they premiered six years before Marvel began to build the first comic book “cinematic universe,” and they avoided many of the tedious tropes of modern comic book movies. They stood alone. There were no crossovers, you weren’t missing important background if you hadn’t seen the latest Blade movie or whatever, and memberberries were used only as delightful seasoning.13 Raimi's characters are not always crackin’ wise, but that’s okay, because they have souls.

Next was the Orci/Kurtzman “Amazing” duology, starring Andrew Garfield.14 Garfield is stellar, but The Amazing Spider-Man is astonishingly decadent. Amazing fans get mad at you when you compare it directly to the Raimi films, but it’s impossible not to, because The Amazing Spider-Man’s entire plot is controlled by the Raimi films. Uncle Ben still has to die, but he has to die slightly differently, so you don’t quite see it coming. He has to say the line, but it can’t be quite the same line, so instead he garbles it: “If you can do good things for other people, you have a moral obligation to do those things. Not choice. Responsibility.” Peter Parker still has to find his way to a wrestling ring and eventually get bit by a spider, but both have to be in weirdly different contexts from the earlier movie. Peter needs a girlfriend, but it can’t be Mary Jane, because she was the girlfriend in the Raimi movies, so now it’s Gwen Stacy. The post-9/11 New York Strong fanservice scene from Spider-Man is totally different, yet tonally the same—and much more jarring in 2012 than 2002.

The Amazing Spider-Man tries to convince you that it’s a good movie by echoing Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man at every turn, hoping that will make it good by the transitive property… while simultaneously trying to be 25% different in the details to stay “fresh.” This does not work. The Amazing Spider-Man retreads old ground, adding little in the way of surprise and nothing in the way of the human experience. The film is an artistic failure.

It also made $262 million domestic and finished sixth on the 2012 charts.

The Amazing Spider-Man 2: Rise of Electro is little better, and in some ways worse, becoming the fourth Spider-Man movie (out of five that then existed) to feature Peter’s fraught relationship with the Green Goblin… and the first to have absolutely nothing new to say about it. Nonetheless, that sequel made $203 million domestic, finishing tenth on the 2014 chart.

When Tom Holland’s Spider-Man was announced, now under the Marvel Studios banner, I was ready to beat my head against a wall. We were going to have to watch Uncle Ben get shot again. They were going to try to change all the little details to make it work slightly differently from the previous movies, while still keeping all that was essential in the Raimi formula. I didn’t have the word for it yet, but I dreaded the decadence of it all.

Then Spider-Man: Homecoming came out, and it gleefully defied decadence. Some smart writer apparently said, “Hey, everyone knows Spider-Man’s origin story, so let’s just skip it,” and they went with it. In previous films, Peter Parker was defined by his relationship with his foster parents and his girlfriends. Homecoming is all about Peter’s relationship with Tony Stark, introduces a very new factor named Ned, and didn’t even tell us M.J.’s name until the last scene. Nobody says “with great power comes great responsibility,” or anything close to it. It ends with a joke about Aunt May dropping the f-bomb. The movie plays like nothing we’d seen before in Spider-Man movies.

Homecoming is not Great Art. It’s trying to be a simple comedy, and largely succeeds. But Homecoming does a good job resisting decadence. It insists on telling us a new story instead of feeding us memberberries from older and better films. If that new story is vague and fluffy as a cloud, that’s still progress in a year defined by The Last Jedi, the live-action Beauty and the Beast, and The Lego Batman Movie. The sequel, Far From Home, continued in the same vein, an off-the-wall action comedy. It indulged the audience’s nostalgia only briefly, in its final minute, by returning J.K. Simmons to the role of J. Jonah Jameson that God Himself created Simmons to play. Was Far From Home good? YMMV, but sure! Was it dumb? Frequently! Was it decadent? No.

Then No Way Home hit theatres. Every error that Homecoming had avoided, No Way Home made. The movie’s basic plot is just the classic origin story, delayed by two movies and made 25% different… but still the origin story. Someone Peter loves dies. It’s kinda sorta his fault. She says the line, like Bart Simpson. Then Peter’s multiversal counterparts repeat the line at him, leaning heavily on our nostalgia for their movies.

No Way Home bizarrely inverts the morality here. Traditionally, Peter loses a loved one because he refused to do the right thing, and the death catalyzes him to commit to a hero’s morality. In No Way Home, though, she dies precisely because Peter was trying to do the right thing. Her death should (by the logic of the story) catalyze Peter in the opposite direction. It should show him that Good Is Dumb and that he should pursue vengeance.

He chooses good anyway because… well, actually, it’s not very clear why. Two strangers tell him it’s a bad idea to be bad, and repeat May’s line back at him? I guess that’s enough, because, after that, Peter’s 100% fine, back on the path Aunt May set for him. Even if you buy this, what was the point of killing her? The consequences of her death are completely resolved within 11 minutes of her last breath. The balance of the film would play out exactly the same if she’d lived.

The whole sequence verges on incoherence. It “works,” however, because we, the audience, ignore all that! We’re too busy remembering other, better versions of the “with great power comes great responsibility” speech to notice that this one doesn’t make any sense—which is exactly what the movie is counting on us to do. That’s a toxic level of nostalgia.

That describes most of the movie. ‘Member Doc Ock? ‘Member The Lizard? ‘Member how Tobey Maguire didn’t need mechanical webshooters? ‘Member how Andrew Garfield got robbed of closure? ‘Member Matt Murdock has superhuman reflexes? (Hope you saw Daredevil, or that’s just an ostentatiously weird moment!) Then they fight. The end.

My heart’s not made of stone. The scene where M.J., Ned, Andrew Garfield, and Tobey Maguire met had me in stitches. I just now watched it again, and it’s still very funny. Ned’s Lola asks Andrew to clean a cobweb! “I hope it’s okay I just came through this, uh… oh. Just closed.” Gosh, Tobey, I missed you and your dumb little face. But these pleasant tingles are not a healthy way to spend a whole movie.

Let the past die. Kill it if you have to. But in Italian.

No Way Home sacrificed everything the Marvel Spider-Man franchise once stood for when it brought back Green Goblin (now a villain in seven of the ten Spider-Man films)… and then, for no reason but an internet meme, had him say, “You know, I’m something of a scientist myself.” Too much of this movie isn’t movie at all, but the reanimated husks of other, better movies. This isn’t art. It is purposeless. It is repetitious. It is masturbatory. It is decadent.

It is the least of this movie’s problems.

Futility

The multiverse has been invented three times.

The first time, it was to provide a possible explanation for certain counterintuitive findings in quantum blah blah blah.

The second time, the multiverse was invented so comic-book writers (and everyone else, soon enough) could more easily harvest the low-hanging fruits of decadence and efficiently convert them to cash money.

The third time, the multiverse was invented to kill God.

The first multiverse, we don’t need to discuss. The only thing it does is provide audiences with a vague but comforting feeling their comic book movies are somehow grounded in The Science. (They aren’t, but no matter.) Quantum mechanics has nothing to do with modern art about the multiverse.

The second multiverse was invented (appropriately) in comics. In 1956, The Flash revamped, erasing its original 1940s hero, Jay Garrick. Even in 1961, though, comic fans loved to tingle their memberberries, so, five years into the reboot, the writers thought of a way to bring him back: the new Flash, Barry Allen, visited a parallel universe where Jay Garrick existed. Now DC, Inc. could sell comics starring either Barry Allen or Jay Garrick!

This started out as regular decadent nostalgia, but spiraled out of control. The number of possible universes quickly multiplied toward infinity, in infinitely small variations. For example, “Earth-2A” exists solely to explain certain minor continuity errors. “Earth-32” is identical to “Earth-1” except that the Green Lantern married his crush in that universe. “Earth-100” is a reset-button for the Teen Titans so they can have smartphones. This allowed comic writers to backtrack key creative decisions by exploring “alternate worlds” where things had gone differently. These alternate worlds would be altered enough to feel “fresh,” but similar enough to make everyone feel all tingly because Superman is still around (he’s just a bad guy called Ultraman). These universes were also similar enough that writers could tell basically the same stories in a very slightly altered setting, counting on the tingly feeling to keep everyone distracted from the repetition. This is classic artistic decadence.

Deeper implications soon made themselves felt.

When you face a difficult choice, you must commit yourself to one or the other. Go to college, or join the Army? Marry your girlfriend, or break up? Whatever choice you make, you can only make one. You and everyone around you must live with the consequences.

In a multiverse, though, you don’t choose one. You choose both. The moment you make your choice, the universe splits and creates two universes: one where you marry the girl, another where you break up. In the real world, this theory is unsettling. In art, it’s fatal, because what’s even the point? Why should any of Superman’s hard choices interest me, since I know there’s another Superman out there who did the opposite? Why should I care whether the Batman of Earth-1 lives or dies in his latest fight with the Riddler, when I know that there’s an absolutely indistinguishable Batman on Earth-13775 who will die if “my” Batman lives, and vice versa? I can make myself care, but only by deliberately not thinking about it, by tricking myself into believing that the Spider-Man of Earth-199999 is unique, even when the whole point of No Way Home is that he isn’t.

Worse, a few years from now, there’s a good chance that the publishers will “merge” the various universes and undo whatever happens in the current story anyway. DC Comics alone has slammed the “reset button” on its multiverse (rewriting and undoing old storylines en masse) eight dang times since 1985, in storylines from Crisis on Infinite Earths to Dark Crisis. Even a noble death, bringing a character's story to a definitive end, can easily be reversed using multiversal shenanigans (which, indeed, is just what happened to Barry Allen).

Because the multiverse makes every possibility real, choices don’t matter. Consequences don’t matter. Nothing matters. When everything simply is—everywhere, all at once—heroism and villainy are both impossible. The comics even have a phrase for letting your shields drop to actually contemplate the sheer, utter, horrifying pointlessness of it all: the Anti-Life Equation, which now supports the barriers between universes, ironically sustaining the multiverse.

No Way Home addresses all of this by ignoring it and hoping you won’t think about it. However, two recent shows have attempted to meet the horror head-on: Rick and Morty and (of course) Everything Everywhere All At Once. Neither succeeds, or even comes close. (Fair warning: spoilers ahead.)

Rick and Morty faces the absolute futility of the multiverse by embracing mad multiverse-hopping genius Rick and his abjectly insane nihilistic hedonism. Rick is the kind of man who takes lives and destroys marriages to get some of McDonald’s discontinued Szechuan chicken sauce. All Rick wants is to do whatever he wants in the moment, to satisfy whatever urge steals up on him, because… what else is there?

The response, from Morty and his family, is (well, sometimes) to seek out the love of family and the attachment of relationship. Yet this is just another version of Rick’s philosophy, with the desire for family and attachment no more than another urge to be satisfied. The happiest man in the family seems to be patriarch Jerry, because he is simply too stupid to understand the absurd indifference of the world into which he’s been born:

“Nobody exists on purpose. Nobody belongs anywhere. Everybody's gonna die. Come watch TV.” —Morty

Everything Everywhere is wise enough to realize that hedonism is not enough. The villain simply wants to stop hurting, to stop feeling, to finally, finally, stop. Facing the eternal suffering of a meaningless life in the infinite multiverse, Jobu Tupaki is making the only rational choice: suicide (by way of omnicide). Her mother tries to stop her. Only the remarkable acting of Michelle Yeoh, Stephanie Hsu, and Ke Huy Quan could convince us that this weak tea could bring anyone back from the depths of multiversal despair:

WAYMOND: You tell me it's a cruel world, and we're all running around in circles. I know that. I've been on this earth just as many days as you. When I choose to see the good side of things, I'm not being naive. It is strategic and necessary… This is how I fight.

And later:

JOY/JOBU: Why not go somewhere where your daughter is more than just… this? Here we only get a few specks of time where any of this makes any sense.

EVELYN: Then I will cherish these few specks of time.

It’s certainly better than Rick. My heart’s not made of stone, reader; of course I teared up; Everything Everywhere earned its Oscars. This climax is closer—much closer—to recognizing the final end toward which the human being is by her nature directed: to seek the good in herself and others. But it doesn’t recognize this natural goodness as an objective feature of reality. It adopts goodness as a “strategy,” a manufactured expedient against despair. It replaces Rick and Morty’s nihilistic hedonism with nihilistic tenderness.

(And—say it with me, longtime De Civvers!—tenderness leads to the gas chamber.)

No Way Home really doesn’t want to talk about any of this.15 It wants to use the multiverse to have the Spider-Mens crack wise about their outfits and their incipient sciatica. It wants to harvest the multiversal memberberry crop without accidentally showing the audience the soul-crushing futility of their meaningless existence. So it skims shallowly over the surface of its own fictional reality. Perhaps that’s the wisest course; there seems to be nothing at the bottom of the multiversal bucket besides Hell. (Maybe something worse.) Yet Marvel’s “Phase V” movie series has promised to plumb its murky depths.

But hey! Nice to see Tobey again!

Unfortunately, No Way Home can’t escape this futility, even by ignoring it. Like a dead god, the multiverse reaches up from cyclopean depths even as the film tries desperately to outrun it. Its tendrils are everywhere.

Determinism

Literature is about character, and characters are about choices. We read (or, less excellently, watch) The Lord of the Rings for the spectacle, the atmosphere, the lore—but we remember it for Boromir’s choice to repent (“Nor our people fail!”16), for Denethor’s choice to despair, for Sam’s final perseverance.

“It is our choices, Harry, that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities,” says a magisterial Albus Dumbledore, explaining the moral of Book Two… even as he hides all his own morally searing choices, his deep and well-earned distrust of himself, until they can hit the reader much harder in the final books.

Brideshead Revisited is a three-hundred page novel building up to a man’s choice to move his hand a few inches—a single, silent, private gesture—and yet that choice is received like “the veil of the temple being rent from top to bottom,” and effectively ends the novel.

Flannery O’Connor said that the heart of a story is “the action of grace on a character who vigorously resists it”—sometimes successfully—because “grace changes us and the change is painful.” Her most famous story, “A Good Man Is Hard To Find,” hinges on the moment when a serial killer is given the precious grace of a completely free choice, and makes one.

No less an authority than Philomena Cunk cuts to the heart of the matter:

That’s the basic difference between Hamlet and Taken: Liam Neeson makes up his mind.

This is what our stories are all about, kids: the mystery of human freedom. You can read about the Laws of Motion or the Laws of Economics or the Laws of Metaphysics in a textbook, but there is no textbook for the Laws of Choice. For the ultimate mysteries of the human heart, there is only fiction.

Sam Raimi understood that. All three of his Spider-Man movies are, first and foremost, about choices.

He is not subtle.

In the first movie, Norman Osborn literally screams at Spider-Tobey, “We are who we choose to be!” That is a pretty good thesis statement for the whole movie. Peter Parker, of course, famously chooses to be the good guy—but not until after his initial choice to be the bad guy leaves Uncle Ben dead by gunshot. Less iconic, but no less vital, is Norman Osborn’s parallel descent into evil—a choice he makes with full knowledge and full consent of the will. The Green Goblin and Osborn start out separate, but Osborn embraces the Goblin, one step at a time, until he is well and truly damned. He spends his final moments pretending that the Goblin was “controlling” him, begging for mercy, calling on all the ties of blood and water… all so he—he, Norman Osborn—has time to line up the perfect kill shot on his son’s best friend.

Spider-Man 2 is so hammer-thuddingly obvious about choices that it hardly bears mentioning, but, in case you haven’t seen it recently, Peter has to choose between his life as Peter Parker and his life as Spider-Man. During his crisis of faith, he loses his powers. That's the plot. Meanwhile, the genius Professor Octavius faces his own pride, and chooses to endanger the entire city rather than admit he was wrong.17 Gloriously, in his final moments, he repents and, by a mighty act of will, overpowers his evil robot arms to save the city.

The third movie feels like a big hot cluttered mess on first viewing—three villains! a love quadrangle! new revelations about Uncle Ben! The next time you see it, though, you pick up the throughline that holds it all together: revenge is a swiftly-spreading poison, but drinking poison is always a choice. There’s a great, unsubtle scene where Spidey, in a church belfry, has been allowing an alien symbiote to fuel his hatred, but now he repents and fights it off. Meanwhile, Peter’s rival, Brock, deservedly humiliated hours before, prays ever-so-piously in the sanctuary below… for God to kill Peter Parker. The poison passes straight from one to the other, first figuratively, then literally. It’s everywhere in this movie, revenge feeding revenge feeding revenge. The cycle is broken, finally, only by the painful choice to forgive. I’ve always stanned Spider-Man 1, but, on this rewatch, Spider-Man 3 turned out to be my favorite.

No Way Home has a radically different view of villainy. In No Way Home, evil is not a free choice made by free agents. Evil is a technical defect—a computer bug in the programming of the human mind.

Spider-Man resolves to help the villains who have shown up in his universe. By “help,” Peter does not mean that he is going to take them to a priest to confess their sins, or to the police so that they can make restitution for their crimes. Peter is going to use technology to reprogram them, because bad guys are (apparently) just defective good guys.

This sounds like the setup to a villainous origin story about scientific hubris leading to moral catastrophe… but, no, actually, the movie is 100% behind Peter’s reprogramming idea. It succeeds brilliantly. The only roadblock is that, by ill luck, one of the “defects,” the Green Goblin, “takes over” “Norman Osborn” at a very inconvenient moment and sabotages their effort. After some meaningless plot, Spider-Man nevertheless jabs Osborn with a green syringe that contains the “cure” for being the Green Goblin, and it works a treat.

This is a travesty.

At one level, it’s just bad writing. No Way Home resurrects the Sam Raimi Green Goblin, but rewrites his character, morality, choices, and arc. In Raimi’s Spider-Man, Norman Osborn embraced the Green Goblin because, deep down, he wanted to be the Goblin. In No Way Home, the Goblin is a disease, like Tourette’s or demonic possession, while the “real” Norman is still inside, fighting against the Goblin that has taken him over. But that’s a lie! The horror of the first movie is that Norman never really fought at all.

No Way Home does the same thing, more or less, to every villain. Doctor Octopus, pulled into the Tom Holland universe at the moment of his death in the Tobey Maguire universe, has apparently forgotten that he just now repented, mastered his arms, redeemed himself, and chose to die a hero.18 Instead, he comes through the multiverse portal in full villain mode, ready to kill Peter, completely enslaved by his robot arms. Once Peter (non-consensually) repairs Otto's inhibitor chip, Doc Ock abruptly becomes a good guy.

One more and I’ll stop: No Way Home does Electro dirty. Electro was one of the only interesting people in The Amazing Spider-Man 2, a lonely, nerdy social cripple who resents his bullies and craves (above all things) normal human friendship with anyone who will have him. He never really gets a free choice to embrace villainy; Amazing 2 (which is not a good movie) bullies him into it by putting Electro into a circumstance where he is bound to misunderstand Spider-Garfield’s good intentions and react badly. Having been forced to choose villainy, though, Electro at least chooses it fully. After a lifetime of meek subservience, Electro becomes a mentally fragile cauldron of murderous resentments… until he shows up in No Way Home, where he’s just the self-assured Black comic relief. Max Dillon, the awkwardest man alive, is suddenly quippy. Worse: he is not motivated by hatred, but by physical lust for electricity. Cure his hunger for electricity, and you cure the man.19 His evil is no longer a problem of the human heart. No Way Home has reduced it to a technical problem.

This brings us to the deeper problem, the real travesty: these villains are not human beings. They are automatons with brains instead of CPUs, locked inside Skinner boxes to pursue their internal reward functions. They live by pre-written brain programs—which they do not control—that will determine all their actions until the programs end at brain death. They themselves choose nothing. It is absurd to ascribe moral responsibility to them at all (whether their acts are good or evil), because none of them exercise true control over those acts. “It is not that they are bad men,” wrote C.S. Lewis. “They are not men at all; they are artefacts. Man’s final conquest has proved to be the abolition of Man.”

We know that they don’t have to be like this, that there could be choices, because we’ve seen the Sam Raimi movies we’re human beings who’ve lived long enough to make at least one effort of will. That is, you’ve lived through a situation where the difference engine in your brain, based on your nature and your nurture, computed that your strongest desire was for X… and yet you found it necessary to resist your own strongest desires and tried to choose Y instead. (Maybe you succeeded, maybe you didn’t, but you tried.)20 These efforts of will are at the heart of all the great literary moments I mentioned above, indeed all literature from The Book of Genesis to Sam Raimi’s taut crime thriller, A Simple Plan (1998). Their absence in No Way Home is all the more obvious because these villains made efforts of will in previous movies, and No Way Home had to do a lot of extra work to reduce them to automata. They were once men; now they are Lewis’s “men without chests.”

Nothing else is possible in a multiverse. No one has agency in a multiverse. For any given decision you could have made, there’s a version of you, somewhere out there, who made it… and another who didn’t. Our conscious minds, with no actual control over the mindless infinitude of the cosmos (or even over ourselves) are damned to merely observe one infinitesimal slice of our infinite multiversal selves—like water in a river when it comes to a fork, sluiced down one side or the other by chance. Once you fully embrace this theory of existence (or any other theory of existence where moral responsibility is impossible), you can’t write movies like Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man.21 Fatally undermined by this determinism, literature stops functioning as a means of exploring free will.

At best, determinist literature is a tool of psychological analysis. These stories acknowledge that humans have no ultimate say in their own decisions, so instead explore the external factors that lead to decisions. Here enters the Trauma Plot, which examines how past external traumas shape (or warp) the present actions of their victims. (I have written about the Trauma Plot elsewhere.) At worst, determinist literature is just one damned thing after another, a meaningless ramble through some arbitrary slice of reality. Its purpose is to distract you for a few minutes, maybe give you a few chuckles on your way to a death you can't stop after a life you can't choose.

No Way Home is determinist literature. No one in this movie is more a prisoner of it than ostensible hero Peter Parker himself. He has a few of what I call “choice-like moments.” He decides to steal the magic murder box from Dr. Strange; he decides to stay the course after Aunt May’s death; he decides to spare Green Goblin in their final confrontation. But none of these were really free choices.

Peter is never remotely conflicted about the magic murder box. The instant he discovers that it will kill the bad guys, he is going to seize it from Strange, because (as M.J. says) “that’s not who he is.” Peter’s existing habits and sentiments never would have allowed otherwise. Following well-worn habits and sentiments is how most of us live out most of our days (which is why it’s important to make good habits). We could say, generously, that Peter’s instinctive reaction speaks well of his past choices to cultivate these habits. But an instinctive reaction is not, itself, a choice.

We’ve already explored how Peter’s decision to not avenge May depends on nostalgia and is incoherent. It’s not a choice.

Finally, Peter doesn’t spare Green Goblin at all; Spider-Tobey physically prevents him from killing Ol’ Gobbo. It’s a gorgeous couple of shots with some beautiful acting by Tobey’s dumb little face. It’s not a choice. Spider-Garfield breaks the stalemate by tossing Peter the goblin reprogramming juice, leaving Peter with no excuse for murder. That’s not a choice, either.

There is one moment later on, though, where an opportunity arose for Peter to defy the logic of his cosmos by choosing to change. A moment where it seemed as though the action of grace might actually be working on him. A moment that would have played very differently in previous spider-films.

See, back at the beginning, before all the nonsense, we learned Peter’s central flaw in this movie: he takes too much responsibility on his own shoulders. He takes actions, often dangerous ones, in order to benefit the people he loves, but he does not consult the people he loves. His friends tell him it’s okay that they were (unjustly) rejected from M.I.T.. Instead of accepting that, Peter tries to control their lives for their own good, which causes all the disasters of the movie. The movie is well aware of this: Doctor Strange (who is insanely irresponsible throughout) berates Peter for it, but M.J. puts it more kindly:

M.J.: You were just trying to fix things. And so... maybe just run it by us next time, you know? That way, when you're thinking, "Hey, I'm about to do something that could, um, break the universe," we could like, help you? Workshop something, or... brainstorm ideas.

PETER: Deal.

Going behind your friends’ backs “for their own good” is a human enough character flaw. You would normally expect a movie to show us how Peter either grows and eventually overcomes this flaw (comedy) or doesn’t (tragedy). Instead, the movie completely forgets about this for the next hour and a half, until Peter is forced to erase everyone’s memories. Now, finally, we return to the question of whether Peter will trust his friends. He explains the situation to them. They make their judgment very clear, and Peter swears up and down that, this time, he does trust their judgment and will do as they ask:

PETER: I'm gonna come and find you, and I'll explain everything. I'll make you remember me. It'll be like none of this ever happened. Okay?…

NED: You promise?

PETER: I promise. I’ll come find you.

M.J.: …I love you.

PETER: I love—

M.J.: Just wait. Wait and tell me when you see me again.

When Peter does see her again, a few weeks later, the spell has worked, so M.J. has no idea who he is. Neither does Ned. They have gotten into M.I.T., though. Peter doesn't know what to say. He stumbles over his words, fails to even properly begin the (weak) speech he has (badly) prepared. He sees their success and thinks they are happy. He sees M.J.’s head wound and blames himself for it. He smiles.

He betrays them.

Peter abandons his promises, abandons his friends (who told him very clearly that they need him), and walks right out the door with that self-satisfied smile on his face. He goes up to an apartment to enact a closing scene of shameless decadence wherein he re-establishes Spider-Man's status quo ante Homecoming.22 Peter hasn't changed at all. The same boy who didn't believe his friends when they said M.I.T. wasn't the most important thing, who went off and wrecked the universe for their benefit without asking them, has gone and abandoned those same friends, the people who love him most, without their knowledge and explicitly against their consent.

If this were a world where choice was possible, you could blame him for this. It’s the only moment in the movie that actually looks like a choice. So you could interpret this scene as Peter freely rejecting the grace offered to him by his friends. Indeed, it could be a powerful bit of storytelling to have the character commit such a serious moral failure in the face of temptation, especially here at the end of the movie.

Alternatively, had Peter overcome his temptation here, that would have been evidence that this is a world where an effort of will can overcome determinist desires. For example, he could have walked out the door because of his temptation, but then returned a minute later to do the right thing and tell his friends, like Han Solo at the end of the first Star Wars. It’s a bit well-worn, but still serviceable.

Instead, Peter just leaves, and the rest of the film (especially its treatment of the “villains”) makes clear that that’s just the kind of world this is, so you can’t blame him at all. The movie certainly doesn’t! The movie seems to believe that Peter was always bound to betray Ned and M.J., because he is just someone who does that. Nobody shoved an inhibitor chip into his neck, so he’s trapped.

In the determinist world this movie depicts, everyone does what their brain-code instructs. There aren’t good and bad people, just good and bad code. There certainly aren’t any comedies. There are only tragedies pretending to be comedies and tragedies that aren’t. They both mean nothing.

And I mean nothing.

Nihilism

I wrote earlier that the multiverse was invented three times, but I only explained two.

The third time, the multiverse was invented to kill God.

During the second half of the twentieth century, it became apparent that we are only able to exist because of some incredible coincidences. Fundamental physical constants had to be calibrated just right, or the universe could never have developed matter, much less human beings. Gravity had to have just the right power to hold atoms together without overpowering them. The cosmological constant had to fall into a very narrow band of possible values or nothing could exist. If the universal density parameter23 were not precisely what it is—to a precision of some 55 decimal places—the universe would have extinguished itself long before life would have had time to evolve. And so on. In whatever process formed our universe, unless a huge number of things went exactly right, there would be nobody here to see it.

The probability of this happening by sheer chance is staggeringly low. Scientists who attempted to put numbers on it, like Roger Penrose, tended to come up with lunatic odds like 1 in 10-to-the-power-of-10-to-the-power-of-123, a number larger than the number of atoms in the universe. Putting numbers on it is probably a fool’s errand, because there’s too much we still don’t understand about the fundamental constants that govern the universe, but there is general agreement that the universe is strikingly “fine-tuned” to support life, and that this “fine-tuning” requires a better explanation than blind chance.

At the time these questions began to be asked, there was an explanation readily available and widely acceptable: God did it. The physical universe was constructed to support life because God wanted to create physical life. Problem solved. As the century wore on, the fine-tuning of the universe became a more and more vexing problem for atheists.24 This culminated in 2004, when celebrated atheist philosopher Antony Flew became an Aristotelian deist, largely because he found intelligent design arguments from fine-tuning too compelling to resist.

This simply would not do! Atheists needed another way to explain our universe in light of the latest scientific evidence, and they hit on an idea first suggested by astrophysicist Brandon Carter in 1973: what if there is not just one universe, but a lunatic number of parallel universes?25 If that’s the case, then the lunatic odds against any given universe being capable of supporting life can be explained away! In a multiverse of 10-to-the-10th-to-the-123rd universes, one of them was bound to get lucky, and that universe is our universe. Hey, why stop there? If we posit an infinite multiverse, then there are infinite universes that support life, alongside an unthinkably larger infinity of universes that don’t!

The only difficulty with this many-worlds metaphysics is that there’s no actual evidence for it. Indeed, it is openly motivated by a simple desire to deny the existence of God. Men will literally postulate the existence of infinite imaginary parallel universes in a hypothetical extradimensional hyperstructure instead of going to church, smdh.

I don’t know exactly when the strategy of imagining a multiverse to deny God migrated from academic philosophy journals to the general public. I first read it in Richard Dawkins’ bestseller, The God Delusion, published 2006. Tonight, ChatGPT suggested to me that Brian Greene’s 1999 book, The Elegant Universe, may have been influential as well, which seems plausible. Regardless, there was a shift around the turn of the millennium. The mathematical multiverse of the quantum physicists and the (admittedly charming) masturbatory multiverse of the comic-book writers slid into the atheist multiverse of the Successor Ideology. What had once been a silly fantasy indulged to sell extra copies of The Flash became a bedrock metaphysical assumption for millions of Americans. (Spencer Klavan wrote a Claremont essay on this last year that was so good, I thought for a while I didn’t need to write this review. Highly recommended.)

When a civilization throws out one theory of metaphysics and replaces it with another, it takes decades for popular entertainment to process the implications. In the meantime, the new theory becomes so natural, so much part of the air we breathe, that nobody thinks of this (very hard) processing work as “doing metaphysics” at all. (Keynes’s quote about dead economists is absolutely true, but the economist in question is usually the slave of an even deader philosopher.) We are twenty years into processing this new metaphysics. Judging by history, that puts us very roughly around the halfway point. Where do we find ourselves?

We’ve discovered that, in our zeal to kill God, we have moved ourselves from a universe where everything matters, especially the unique miracle of every individual life, to a multiverse where absolutely nothing matters, or even could.

Even if something did matter, we couldn’t do anything about it. The concept of free will didn’t raise us to the level of God, the Unmoved Mover, Who acts with perfect freedom, but it did make us (as philosopher Timothy O’Connor puts it) “not-wholly-moved movers,” wielding a power to choose that, in a sense, defeats even God’s omniscience. This free will theory has been under pressure for a long time, thanks to the disenchanted, mechanistic premises of Enlightenment philosophy. However, the multiverse absolutely rules out free will. According to the multiverse hypothesis, for every choice you make, you also make the opposite choice somewhere else. Which outcome your mind ends up observing is a matter of nothing more indeterminate than chance.26

In a reality where nothing matters, and we can’t do anything about it, there’s only one thing we can do: masturbate. Cue Spider-Garfield asking Spider-Tobey, “So, are you going to go into battle dressed like a cool youth pastor?” Quips! No Way Home’s two-hour wank is a better approach than suicide, but I promise it will wear thin. It’s already begun. And then what?

As sexual masturbation wears thin, it seeks novelty. Everyone from the average American YouPorn viewer to the thoroughly evil Marquis de Sade can tell you how easily the craving for novelty turns toward violence. We have yet to see how cultural masturbation (“decadence”) develops as it wears thin, but we can be certain that Everything Everywhere’s “just be kind” speech ain’t gonna cut it. In the multiverse, kindness is unjustified, and choosing it is impossible.

Novelty, too, will play itself out. And then what? The remaining alternative is Jobu Tupaki’s: suicide.

Did you notice how explicitly the widely-beloved series finale of The Good Place glorified suicide?

Did you notice the Season 1 finale of Star Trek Picard doing the same thing?

Did you watch the Canadian fashion retailer commercial doing the same thing—but this time for an actual person?

And then what?

These aren’t questions a review of Spider-Man: No Way Home can or should answer. No Way Home is at the peak of the slippery slope, high above those threatening “And then whats?” However, they are questions that you should ask yourself, whether for the thousandth time or the first, once you see No Way Home.

Just Another Tuesday

At the end of a 10,000-word essay linking the new Spider-Man movie to the destruction of Western civilization, you’re probably thinking that I really hated the movie.

Thing is, I didn’t hate it. If you hate a movie, you write 750 words roasting it alive, hit Post, and have some crumpets. You only go full Red Letter Media if the movie is a symptom. I gave No Way Home two-and-a-half stars in my Letterboxd review (half a star more than I gave The Amazing Spider-Man), and I stand by that. I enjoyed myself immensely in the theater. I enjoyed myself immensely when I rewatched chunks for this review. It’s a very well-made work of distracting decadence. I went home with all the right endorphins.

The cultural and moral rot at the heart of No Way Home is in no way unique to No Way Home. No Way Home’s not even the worst example of it. I wrote about No Way Home because this movie is what you get when the rot has set in so deep that Hollywood writers put it into pure-hearted popcorn flicks without even noticing themselves doing it anymore. We don’t notice it either. It’s become the air we breathe.

Spider-Man: No Way Home didn’t set out to kill God. Imprisoned in the multiverse of modern metaphysics long before its first page was written, Spider-Man: No Way Home couldn’t have even imagined God. (Soon enough, neither will we.)

The cost was that No Way Home couldn’t imagine a real human being, either.

On the other hand, there is a new Spider-Man coming out. I hope as much as you do that this one will—

Ahhhhhh, f—

UPDATE 3:16 PM: In the original version of this blogletter, I claimed to have “rewatched not only No Way Home, but all ten Spiders-Man.” However, I can’t count. There are only nine Spiders-Man. I regret, and have corrected, the error.

The truth is, Girlbusters was fine. I laughed several times. It deserved neither the adulation it received from the goodthinkers nor the hatred of the wrongthinkers.

Luke Skywalker died as he lived: an introspective, often whiny hero who never won a single filmed lightsaber duel or really did anything even slightly impressive as a Jedi. (Yes, he blew up the Death Star, but Ahsoka Tano could have hit that shot at the age of 12 with the blast shield down.) Seriously, go rewatch the Original Trilogy and try telling me Rian Johnson misunderstood the character, not you. Too bad the rest of TLJ was a mess—we’ll get back to that—but there’s like a third to a half of a good movie in TLJ.

Irredeemable drivel, and it proves it by trying so very very hard to redeem itself with lovable characters, ear-candy dialogue, and strong emotional beats. The problem is that you can’t spend half your movie’s runtime trying to ctrl-z the previous movie because you’re mad at it. You have to build up a credible story of your own. Without it, everything thuds, no matter how sparkly. When you enter a story mid-telling, you have to build up, not tear down… and J.J. has always struggled with endings, always, right back to Super 8 and Alias.

Discovery’s first season redeemed several previous seasons of Star Trek (TNG S1, ENT S2, TOS S3, DS9’s Ferengi episodes) by proving that, yes, it is actually possible to produce worse Star Trek than that—by an order of magnitude. Even taken on its own terms—“it’s a Mary Sue fic but it’s okay because it’s diverse and edgy”—I have genuinely, honestly read better Star Trek written by online roleplayers who embarked on the same edgy-but-diverse mission for Bravo Fleet. (I dragged out this insight well past the point of coherence in my single discussion of Discovery on De Civ.) In future seasons, Discovery released a smattering of episodes that might plausibly be called actual Star Trek of the most deeply mediocre quality, then finally graduated to sheer unrelenting boredom. Season 3 broke me into indifference, and Season 4 is the first season of Star Trek ever produced of which I have not seen a single episode (and likely never will).

Discovery is nevertheless still head-and-shoulders better than the calamitous Star Trek Picard.

Everyone loves Strange New Worlds because they’ve been so deeply abused by Discovery and Picard that they’ve forgotten that Star Trek can actually be good, and are therefore willing to settle for a series that consists of nothing but warmed-over rehashes of better episodes from better times. I include myself in this. (That said, y’all shoulda been a lot nicer to “Fight or Flight” when it came out if you’re going to fawn over it when it’s re-released as “Children of the Comet”!)

I didn’t want to be a hater. Eleven-year-old me was furious and alarmed about Enterprise, but it won over my hateful little heart by the end of the pilot. I entered Discovery and Picard determinedly optimistic. But bad is bad, and it’s okay to say so.

I didn’t watch it, but I trust Ross Douthat’s demi-review is correct in the essentials.

Did not see. My commitment to watching every Marvel movie ended with the sense of wholeness and completion that I felt after Endgame, specifically this moment.

It genuinely baffles me that anyone has seen these, when the originals are already great and right there on your old pile of VHS’s. You shouldn’t remake good movies; you just re-release them! You remake bad movies to make them better! Yet 2019’s Aladdin made a billion dollars worldwide so I clearly don’t understand the world at all. We will return to this, perhaps, later in this review.

November 2022. I type slow.

This review is dedicated specifically to subscriber Paul M., who justifiably believed I would never finish it, which gave me the gas to do just that. So don’t worry, Paul! I do finish things! Today, Spider-Man; tomorrow, A Chiora Family Christmas!

Hollywood has always enjoyed its fair share of sequels, remakes, and reboots, and it is an ancient rite of old grumps and conservatives (but I repeat myself) to complain about it. Sensible people have developed a knee-jerk suspicion about any accusation that Hollywood has “lost its creativity.”

On the other hand, compare this year’s Top 10 highest grossing films to the Top 10 of 2002:

This Year - 2022:

Top Gun: Maverick (sequel)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (sequel in franchise)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (sequel in franchise)

Avatar: The Way of Water (sequel)

Jurassic World: Dominion (sequel in rebooted franchise)

Minions: The Rise of Gru (sequel)

The Batman (launch of fourth rebooted franchise)

Thor: Love and Thunder (sequel in franchise)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (sequel in third rebooted franchise)

Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (sequel)

Two Decades Ago - 2002:

Spider-Man (adaptation, but neither a sequel nor consciously a franchise)

Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (sequel in rebooted franchise)

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (sequel)

Signs (original)

My Big Fat Greek Wedding (original)

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (sequel in adaptation)

Austin Powers in Goldmember (sequel)

Men in Black II (sequel)

Ice Age (original) (hard to recall the days before Ice Age was a franchise!)

A Beautiful Mind (original)

This follows a steady pattern that has lasted several decades:

Originals have gone from roughly 90% of the Top 50 to perhaps 30-40%.

Well, not quite true. Lucas got one good movie out of the prequels: Revenge of the Sith is a pretty good flick and I’ve said so since it came out. Phantom Menace is a mess, though, and Clones actively painful to watch without a fan edit handy.

On the other hand, Clones is an absolute meme factory. Also, surprisingly, although it is the worst of the six, it is not the movie you cut out when watching Star Wars in the correct order.

Four if you count Into the Spider-Verse. I guess you could even go for five if you counted Turn Off the Dark, but, to be clear, don’t.

By way of illustrating the difference between an inspiration and a memberberry, it is worth noting that important parts of Spider-Man’s climax were very obviously based on the 1973 comic book storyline, The Night Gwen Stacy Died. In that story, the Green Goblin uncovers Spider-Man’s secret identity, throws Spidey’s love (Gwen Stacy) off a bridge, Spider-Man accidentally kills her while trying to save her with a web, and Green Goblin accidentally kills himself during a final, vengeful confrontation with Spider-Man. Several very similar things happen in Sam Raimi’s first Spider-Man.

However, very few people in the movie audience were aware of this, the movie did not ostentatiously call attention to it, and the movie worked just as well (maybe better) if you did not “get the reference.” Compare this to, for example, The Force Awakens’ abject dependence on the audience’s recognition of (and outright reverence for) the Millennium Falcon and Han Solo.

This is entirely unrelated, but I want to put in a good word for Bob Orci here. After an incident in 2012, when he insulted a Star Trek fan who asked him a question in a comment thread, Roberto Orci received a reputation as some kind of high-handed fan-hater. This reputation is undeserved.

From 2008 to 2012, Orci was a very active participant in Star Trek fandom. Not since at least Ronald D. Moore has Star Trek had a producer who made it a point to regularly talk to ordinary fans online. Orci was on the TrekMovie.com comment threads at least weekly. I exchanged words with him on several occasions, and obviously I read his comments religiously, since he would give us an idea of what the Powers That Be were thinking—and he had his own intense fandom to share. (I read Diane Duane’s Spock World on his recommendation, and it remains one of my favorite Star Trek books.)

Over several years of regular comment-thread hangouts with Bob, he was always genial, even in the face of many commenters who didn’t care for his work and weren’t afraid to say so. In the weeks after Into Darkness came out, he snapped, one time only, at a jerk who had it coming—I was in the thread that day and saw it happen live—and boom, that’s the story that got picked up in all the trades. Not “Bob Orci loves hanging out with fans and does so for years” but “Bob Orci wants to punch fans in the mouth and steal their lunch money” because he intemperately told off his three millionth troll.

We never saw Bob again. I always assumed the studio told him he couldn’t hang out with us anymore, because of the bad press. Right-wing YouTubers still tar him with the “fan hater” brush. I don’t really like any of Bob Orci’s movies, many of which fit right into my definition of “decadence,” and hoo boy I could do without the 9/11 truther themes and the panty shots and the braindead plotting and… really everything… in Star Trek Into Darkness, but he’s a very personable guy and a good fan ambassador who got a bad rap. Because of his bad rap, we will never get another honest fan ambassador again.

Fun fact: Chris McKenna, co-writer of No Way Home, also wrote the Community episode “Remedial Chaos Theory,” the multiverse episode that gave us the phrase “The Darkest Timeline” and that gif of Donald Glover walking into a scene of flaming chaos while holding a stack of pizzas. So it’s not that the writers haven’t thought about this stuff! But it would be very unhelpful for No Way Home if you did.

Okay, I admit, that specific scene is better in the movie.

To be fair, Doc Ock is under the influence of his evil sentient robot arms, which reduces his culpability… but, if you watch the scenes again, it seems clear he is not under their control. The arms are the devils on his shoulder, tempting him, but it is pride (born of despair at the death of his wife) that pushes him over the edge. Otto’s in control. That’s why it’s interesting.

Actually, it’s much worse than that, but it involved too many continuity details to bother explaining outside of a footnote.

In No Way Home, Ock describes how he came through the universes: “Spider-Man was trying to stop my fusion reactor. So I stopped him. I had him, by the throat.... And then, I... And then I was here.” There’s only one time during the fight scene in Spider-Man 2 when Doc Ock has Spider-Tobey by the throat. It’s during his repentance, when Spider-Tobey reminds Otto of his own words and offers him the grace he needs to make a free choice against his evil robot arms.

With this one line, No Way Home implies that Octavius was taken to the Holland-verse at that moment. In the other universe, he got his inhibitor chip repaired, then returned at the same instant he left. The implication is that Otto’s change-of-heart is simply because No Way Home “fixed” him. This eviscerates Spider-Tobey’s conversation with him in Spider-Man 2 and deprives the climax of Raimi’s movie of its moral weight. No Way Home not only ruins the character of Otto Octavius for its own purposes; it appears to reach back and ruin the character in the original film as well!

But this also just doesn’t make sense. If No Way Home is correct that Otto pops to a second universe and then pops back to Spider-Man 2 just in time to repent, then Otto is still a couple minutes from death in his world. He has dialogue after this point! He makes no mention in the original scene of having just visited an alternate universe, and his behavior is inconsistent with someone who has just been “repaired.” It’s seems clear that the No Way Home writers simply didn’t think this through, or at least didn’t take enough pride in their work to write something that made sense. Another reason to stick it in a footnote.

Spider-Garfield is permitted one totally implausible line “addressing” Electro’s entire story arc before Electro himself moves on to a Miles Morales joke. At least it’s a funny joke.

Efforts of will do not disprove determinism—although C.A. Campbell certainly thought they did—but they provide ample reason to question it, which is probably sufficient for literature. I don’t have a disproof of determinism, although I have recently become persuaded that agent causation is at least a coherent alternative.

Don’t tell Sam Raimi, though! Shortly after No Way Home came out, Raimi tried precisely to create a Raimi-style choice-driven superhero movie set explicitly in the multiverse. Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness doesn’t really make sense, because Raimi’s theory of free will doesn’t seem compatible with the setting, but perhaps “gleeful defiance of logic” is the best way for a writer to escape the consequences of a bad theory of existence. I’ll deal with all the plot holes by pretending that, somewhere in the background, Sue Storm was helping the Illuminati by invisibly spinning an Infinite Improbability Drive.

Why did we even have Homecoming and Far From Home if this was how it was going to end up? Why? Why not just admit we’re trapped in a reboot doom loop instead of teasing us with something else for four years?

i do not know what this is do not ask me

I’m not actually personally a big fan of fine-tuning arguments for the existence of God. They seem reasonably persuasive given current evidence (although I haven’t looked all that closely), but they are fundamentally empirical arguments based on cosmological concepts that are still not well-understood. Empirical evidence has a habit of changing over time, in unpredictable directions. I prefer my belief in God to be grounded in something a little more long-term dependable than the current shape of the cutting edge in astrophysics, which is why I have spent a lot more time with Aquinas than Hoyle and the fine-tuners.

Disproving fine-tuning may turn out to be as easy as coming up with a grand unified theory of classical and quantum mechanics. That’s pretty hard, but disproving Aquinas would be akin to disproving that a right triangle has 180 degrees, which is quite a bit harder. So I do not have much of a dog in the fine-tuning fight… but, as we are about to see, it has some pretty interesting dimensions.

He called the multiverse a “world ensemble,” which, I have to admit, sounds much cooler.

This also rules out Camus’s alternative of “rebellion against the absurd,” although the difference between “become the Absurd Hero” and “masturbate” is not necessarily all that clear in the first place.

Such a joy to read your excoriation of this movie that so many people loved. And look at how much has gone on in the world that I didn't comment for all this time.

Spider-Man: No Way Home deserves everything you throw at it, as does most of the multiversal MCU. But I question the multiverse trope as the culprit.

Instead of a multiverse, let's imagine we live in just one universe, but infinite in size. If it's genuinely infinite, as you're no doubt familiar, there's another you out there somewhere who wrote this same essay with an opposite conclusion. Not only that, there are infinite yous who wrote roughly the same essay, and it's just a question of how frequent certain iterations are over others. Unlike the multiverse, for which we have no evidence, an infinite universe is fairly probable given what we know. Uh oh. Which version of yourself you perceive is mere chance, not choice.

The final statement in that paragraph is false. Those other Jameses are not you. If we hop through space so that you could visit these other selves, which is all a multiverse amounts to, they still are not you.

The multiverse, even an infinite multiverse, is merely a sci fi trope that can serve a variety of stories. Spider-Man: No Way Home's rot does not lie in using this trope. It lies in mistaking the mechanics of metaphors for their meanings. Your recap of past Spider-Man movies leaves out how each movie featured some physical mechanic for the evil of its villains. In a purely literal take on Spider-Man 2, Doc Ock didn't just choose wrong: he had an inhibitor chip that took a blow at the same time that his wife died and his experiment failed, and then when he's confronted with the consequences of his actions, the tentacles visibly spark and fritz in the water, which lets him reassert control. If you're the writers of No Way Home, you don't recognize how the mechanics of the supervillain are metaphors for obsession, loss of grounding in humanity, and moral choice, and you make the story about fixing the chip. The multiverse trope didn't do that. Storytelling illiteracy did.

Incidentally, this is the same error that we on the left see scriptural literalists as committing. (Not implying you're in that camp.)

Meanwhile, for a multiversal story that isn't a moral black hole, we don't even need to look far. There's one multiversal story in the MCU that had something to say, namely Loki season 1. (Let's please ignore season 2.) What if you kept making the same mistakes over and over? What if every version of yourself you try to be kept failing in the same way? What if you had no concept of any possible version of yourself you could love, or deem worthy of love, or be capable of loving someone else? Okay, now what would it take, and what would it mean, for someone like that to see, and then start to become, someone more than they have been? That's Loki season 1, and as the polar opposite of No Way Home, it uses a multiverse trope specifically to call a character to greater accountability.

Now, about the multiverse killing God.

I've never heard an atheist raise the multiverse idea to argue against intelligent design, mainly because atheists regard intelligent design as silly to begin with. (I won't get into why here because it would divert the discussion.) Needing to invent a multiverse to argue against intelligent design would require granting that intelligent design arguments have validity, which atheists generally don't. Besides, the multiverse as proposed within quantum physics has universes split when particles could go either way, not whole universes with completely different physical laws. So it doesn't even work for this argument anyway. While I'm sure Dawkins used it, because he's a kitchen sink kind of guy and also a jerk, I don't think it figures prominently among atheists, and isn't particularly about killing God.

It's mainly just a lazy way to bring in multiple Spider-Man actors. It's been done to death enough lately that I'd rather not see more of it. But I'm not convinced it kills free will any more than our single universe, and all the deterministic arguments you can make about how it works. It's a sci fi device, no better or worse than faster than light travel, transporter clones, or cybernetic collective consciousness.

Would adding hard boundaries to the Multiverse, like the Constants in Bioshock Infinite, save the concept from determinism?