Some Impromptu Post-Election Thoughts You Maybe Haven't Considered Yet

Or maybe you have. Especially if you read my Facebook.

The advantage of writing all those words right before the election is that you don’t really need to hear from me after the election to know how I felt about it: elated by the victories for fetal rights in Florida, Nebraska, and South Dakota; delighted by the Republicans’ comfortable majority in the Senate and the fall of Tim Walz’s trifecta in Minnesota; in some ways relieved yet profoundly unsatisfied with the presidential result.

Still, somebody asked me over the weekend, “Come on, that can’t be all you’re thinking, can it?” and, I had to admit, she was right. I have some impromptu observations, about various results, from various directions. None of these are long enough to carry an article by themselves, but, combine them all, and I think there’s some interesting material here. In case you want to skip around, here’s a…

Table of Contents

A Ripple, Not A Wave (interpreting the national results)

Stratelegic Implementations of Electoral Strategery (midterms preview!)

The Catholic Vote (why exit polling showed Catholics as Trump+18)

Why Did Harris Do Okay in the Swing States? (two views on the question)

The Glass is Three-Tenths Full (the abortion referenda results)

The Emerging Trump Majority (election’s effect on the Supreme Court)

Imagine a Debate Stamping on a Congressman’s Face… Forever (filibuster)

Untitled President (very preliminary thoughts on Amdt. XIV, Sec. 3)

Prognosticators in the Stocks (polling did well, thanks very much)

These Ones Were Really Wrong, Though (some inside baseball/scolding)

A Ripple, Not A Wave

The American people were deeply dissatisfied with… everything. President Biden’s approval rating was hovering in the low 40’s. Only about a quarter of Americans thought the country was on the right track. Inflation had deeply upset the American people at home, while the Administration’s handling of a war in the Middle East had opened it up to heavy criticism from all sides.

The elections played out accordingly: the Republicans won the House national popular vote by 3 points, although, thanks to heavy gerrymandering on both sides, they gained only a few actual House seats. All blue-state Senate races went predictably to the Democrats. All red-state Senate races went predictably to the Republicans. The purple-state Senate races were decided by close (sometimes razor-thin) margins that might easily have been gone the other way—although poor candidate quality wrecked some promising Republican candidates, like Kari Lake in Arizona. When the dust settled, the Republicans had won a clear victory, but not a decisive one—certainly not the victory you would expect, given all that bad stuff I said mentioned in the first paragraph. Most commentators declared Donald Trump responsible for the result. Trump responded by announcing, one week after the election, that he was launching his re-election campaign.

Because, of course, what I just described was not the 2024 presidential election. I just described the 2022 midterms.

The 2024 election was completely different: in 2024, Biden’s approval rating had sunk to the high 30s (not the low 40s), and, uh…

…huh. I guess everything else holds up.1 Republicans did better in the Senate in 2024, but that’s mainly because the 2024 map was super-favorable to them.2 It also helped that, instead of running freaking Dr. Oz for Pennsylvania’s Senate seat, the Republicans ran Dave McCormick, the much more competent (and much less Trumpy) politician who barely lost the 2022 primary after Trump endorsed Dr. Oz.3

We don’t have a final 2024 House popular vote count, because, well…

…but it looks like the Republicans will probably end up winning the national popular vote for House by about 3 points again. Interestingly, the House Republicans will probably run a bit ahead of Donald Trump’s national popular vote for president: Trump will likely end up winning by only 2 points.4

This was a 51/49 presidential election. It was not a red wave, but a red ripple. Trump got a firm victory, outside the plausible margin of doubt, but not a decisive one.5 Even the Electoral College win is pretty close.

Since these elections were basically the same election, it’s a little strange that the reactions were so different. The Red Ripple of 2022 was a humiliating setback for Republicans that Republicans all felt the need to explain, and which Democrats all felt was a mere prelude to a glorious triumph in 2024. The Red Ripple of 2024 opened a round of “soul-searching” for Democrats and massively overconfident bragging by Republicans about how the country is different now, how “it’s morning in America again.”

Opposite reactions to the same basic result seems to come down to a difference in expectations.

In 2022, the Vibes were all strongly in favor of a “Red Wave,” even though the data never showed that.

In 2024, the data showed essentially a tied race. The Vibes arguably tipped into Kamala territory during the final week of the election. That Selzer poll got a lot of people convinced that Kamala was about to beat her polls. (We’ll talk about that.) People had been talking all year about the possibility that Trump could win again by sneaking through the electoral college again, but almost nobody had reckoned with the possibility that Trump might win the popular vote—despite the warnings:

The first lesson here is one election nerds have learned again and again: people will fail to see what is directly in front of their faces if their prior experience and expectations don’t allow them to see it… and then, if and when they are finally forced to see it, it will come as a huge shock to them and they will exaggerate its importance rather than putting it in proper perspective.

The second lesson is that, since 2022 and 2024 were basically the same election, probably any explanation you have for one that doesn’t explain the other is a bad explanation.

Stratelegic Implementations of Electoral Strategery

After a presidential election where one side loses both the electoral and popular votes, there’s always a feeling / hope / fear that the losing side is doomed forever. The past couple cycles have been weird, because 2016 split the electoral and popular votes, and, in 2020, the losing candidate convinced many of his supporters that his “win” had been “stolen,” but what the Democrats are going through right now is actually normal. You young whelps don’t remember the apocalyptic fear after 2004 that America would be forever controlled by theocratic Evangelical “moral values voters” (HUGE buzzword for the next two years). Or the apocalyptic fear (on the other side) after 2008 that the young, multi-racial “emerging Democratic majority” would soon put an end to the Republican Party forever.

You will notice that neither of those things happened. Indeed, most of these sweeping conclusions about The Larger Meaning Of The Election don’t last beyond the first midterm, when the party out of power moderates a little, blames the party in power for bad stuff a little, and comes roaring back.

On that note, Republicans should anticipate losing the closely-divided House in 2026. Because their Senate win this cycle was so convincing, and the map next cycle remains extremely favorable to them,6 Republicans are likely to retain the Senate in 2026, but nothing is guaranteed. (Remember, most voters still dislike Trump! They voted for him despite liking Harris more!) If the Democrats are able to ride popular anger at Trump to a 2018-style victory, they could indeed take back the Senate.

This is doubly true because Trump’s win in this election depended on huge gains among voters who don’t turn out in every election. The kind of voter who reliably shows up for every election (suburban, female, highly educated, White, older) tends to be the kind of voter who hates Trump. This is a problem Democrats had for decades, notably in the Obama years: Dems could turn out their broad coalition for presidential years, but then they’d get slaughtered in the midterms. Now that Republicans depend on low-propensity voters, is that their future under Trump? If so, midterms could go a lot worse than what Republicans were accustomed to in the pre-Trump days… and it’s not like midterms usually go good for the party in power.

(On the other hand, Trump’s voters apparently turned out okay in 2022, so maybe it will only be a standard-bad midterm.)

The midterm result will depend, of course, on world events and on the economy. There’s a lot of luck involved there. It will also depend on voters not getting really sick of Trump really fast. That’s firmly in Trump’s court, and his track record is… not encouraging.

Let’s look even further ahead. Trump enters office as a lame duck, which creates a strange dynamic in the 2028 presidential race. Usually, the party of the term-limited president loses, because voters are sick of the party in power after eight long years. However, Trump is being term-limited out after just four years. That’s never happened before in American history.7 We really don’t know what the dynamic will be in 2028: will the Republican run as a pseudo-incumbent? Will he want to? Will the voters already be sick of Team Red? We’ll find out in four years.8

One last thing for Democrats to worry about: they lost in both 2022 and 2024 to Donald Trump and the Trumpian Republican Party. It’s possible that, when Trump leaves the political scene, he’ll take his coalition with him and GOP numbers will go down. However, given past data, it seems much more likely to me that GOP numbers post-Trump will go up. Trump seems to be a drag on the ticket, not a boost. So Democrats are currently running against a badly hobbled Republican Party… and still routinely losing. They might need to moderate more than they expect to get back to par with a healthy, post-Trump GOP, at least in 2028 and beyond.

The Catholic Vote

The Catholic vote is a funny bit of Americana. To understand the Catholic vote, you have to understand the quirks of Catholic polling.

Catholicism is a very “sticky” identity. When someone is born an atheist and converts to Islam, he tends to identify in polls as a Muslim, not an atheist. When an Evangelical becomes “nothing in particular,” he tends to identify as atheist or agnostic or nothing in particular. Catholics are weird. When Catholics leave the Church, they are relatively likely to continue identifying as Catholics! This can last for years after the Catholic de-converts, sometimes generations after the family de-converts. For many Americans, Catholicism is a culture, a set of traditions around the Christmas season, not a religion. In the United States, these “cultural Catholics” greatly outnumber religious Catholics.

Because cultural Catholics are basically just ordinary Americans who might say the Hail Mary once in a while, and because there are so many of them, when you poll “Catholics” without filtering for specifically religious Catholics, you’re basically just getting a random sample of ordinary Americans. Their polling responses are basically always pretty much exactly the same as polling results for normal Americans, unless you ask them about St. Patrick’s Day or tacos.

That’s the other thing about Catholics: churchgoing or not, we are disproportionately White (specifically Irish) and Hispanic. Hispanic immigrants are nearly always religious Catholic when they arrive, but their kids de-convert just as fast (maybe faster; I haven’t checked in a while) than the children of native-born Catholics.

These are the keys to understanding the Catholic vote.

Historically, the Catholic vote has tracked the national popular vote for President pretty closely: it split evenly 2012 and 2000, went narrowly for Bush in 2004, went 54/45 for Obama in 2008, split 50/50 in the 2020 election, and was 52/44 Trump in 2016 (its biggest deviation from the norm).

In 2024, early exit polls suggest that self-identified Catholics may have gone for Trump 58/40 — a huge 18-point margin.

A lot of people are wondering whether that’s proof Kamala’s abortion rhetoric, or J.D. Vance’s recent Catholic conversion, or Kamala skipping the Al Smith Dinner, was some huge galvanizing event that polarized Catholics to Trump. Much as I would like for religious Catholics to wield that kind of power, I think that’s almost definitely not the case.

The first concern here is that this is all based on early exit polls from Edison Research. These polls are… not great, Bob. They’re weighted to the final result, and that has some weird distorting effects on crosstabs like “the Catholic vote.” Pew Research will release its study of the 2024 electorate in a few months using a validated voter file and appropriate demographic weighting, and that should give us a much clearer picture of the 2024 electorate. It’s possible that Pew will discover that the Catholic vote margin wasn’t unusually large after all. (Exit polls by the Washington Post and the AP did show smaller margins.)

However, if the 18-point margin holds up, it’s probably still not a sign of particular religious fervor.

You see, White Catholics have been breaking Republican by large margins for decades. For example, in 2008, McCain won the White Catholic vote 52/47. They’ve been balanced out, in recent elections, by even more overwhelming support for Democrats from Hispanic Catholics. (Hispanic Catholics backed Obama 72/26.) In the 2024 election, however, Trump seems to have brought the Hispanic vote to nearly neutral nationwide. That means there’s no longer anything to cancel out the White Catholic vote. Boom. Instant Catholic blowout.

It seems to me that this likely had little or nothing to do with a sudden religious awakening among Catholics. True, Harris was very bad from the religious Catholic’s perspective, but so was Obama, who sued nuns to force them to pay for contraceptives. The bishops were not measurably more pro-Trump in 2024, and may arguably have been slightly more anti-Trump than in the past couple cycles. There’s no particular reason to think that religious messaging suddenly broke through in 2024, and plenty of reason to think that my theory is correct: the Catholic vote swinging so far toward Trump is simply a second-order symptom of a major racial swing that’s affecting all sectors of American politics. (I last wrote about that racial swing when it was only theoretical, back in March.)

Why Did Harris Do Okay in the Swing States?

Speaking of the racial factors of this election…

There is an idea circulating right now among Democrats (including some very smart Democrats I respect a lot) that we know Harris ran a good campaign because of how well she did in the swing states. Here’s Matthew Yglesias:

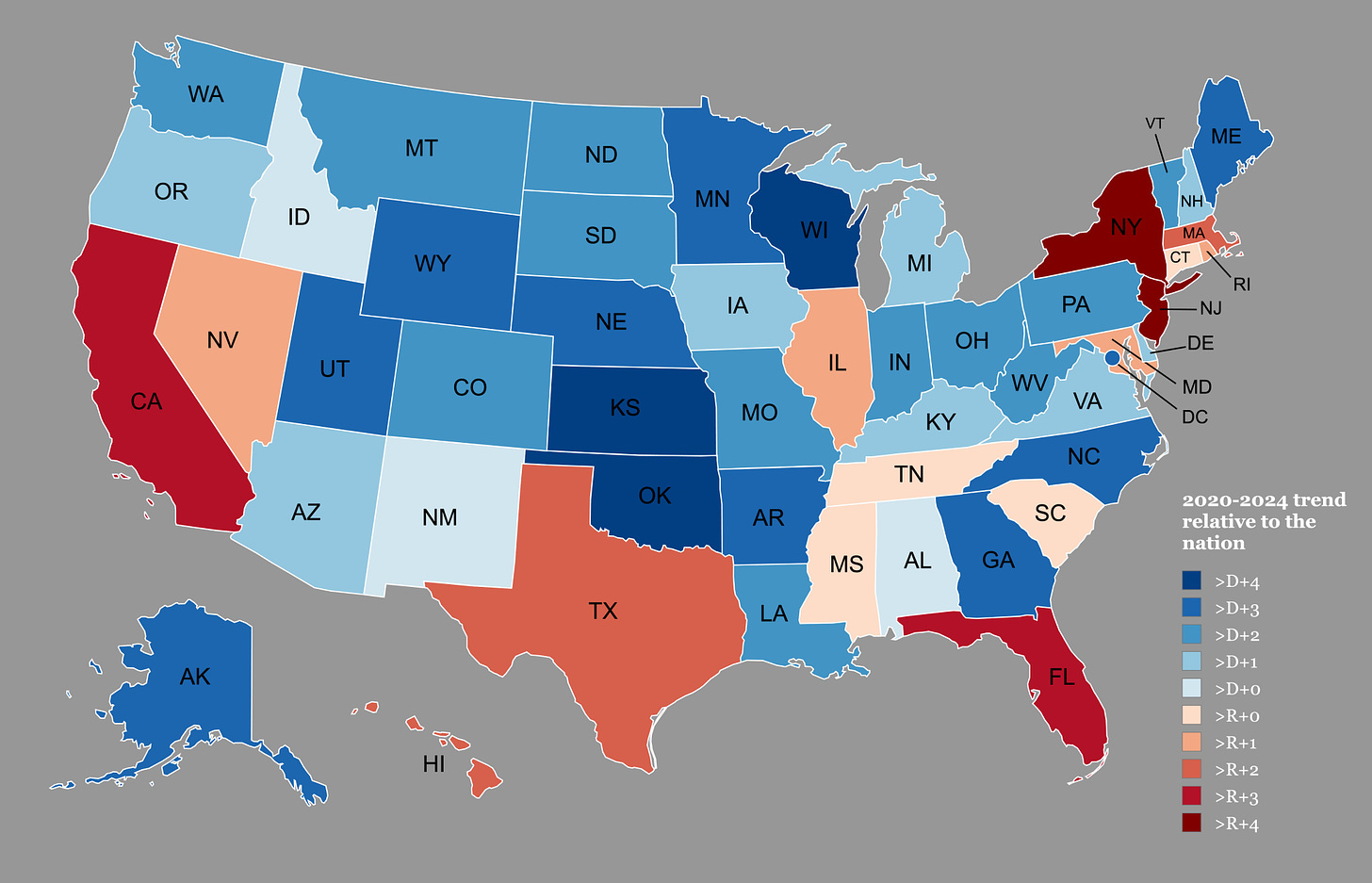

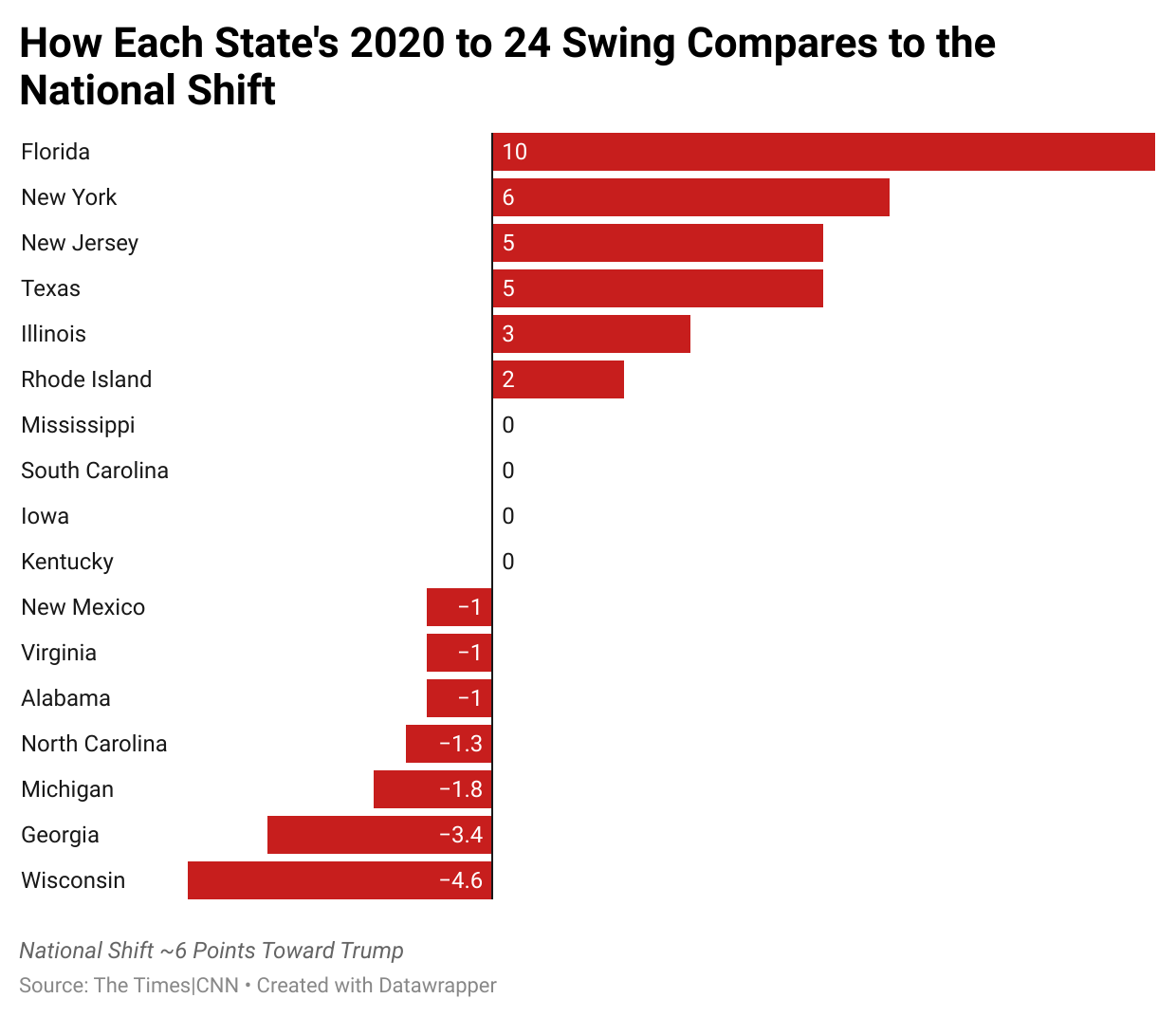

Before we get to today’s mailbag, I wanted to share this chart, because I think it reflects a point that should be central to any sane narrative about the 2024 election. There was a very strong six-point national swing toward Trump, but among the states with complete data, the swing was notably smaller in the core battleground states than it was nationally.

This is important, because it underscores that the net impact of the ad war was strongly favorable to Harris — by a margin of 2-3 points. That’s both to the credit of the Democratic Party’s ad makers and ad testers, but also an important breadcrumb for larger lessons. If we study what Democrats’ ads say, we know what kind of message in earned media could have made Democrats more popular nationally. Not always popular enough to win in the face of headwinds, but it’s still useful information.

This is a pretty interesting theory, and there’s a lot of surface plausibility to it.

However, there’s also reasons to doubt it. Take a look at this larger map (by @_fat_ugly_rat):

When you look at this map, it’s true that Democrats did markedly well at stanching the bleeding in several key swing states: Wisconsin, Georgia, and North Carolina. All these were heavily involved in the ad war, and the Atlanta suburbs are one of the only places in the country where Harris actually gained vote share over Biden.

On the other hand, Yglesias’ chart omits three of the seven swing states: Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Nevada, which also saw heavy investment in the ad war yet aren’t notably bluer than their “peer” states. Indeed, New Jersey has a ton of overlap with Pennyslvania’s media market (my grandparents lived in the Philadelphia blast radius, so I’ve seen this at work), yet was one of the strongest states trending to the right. All this points against the idea that Dem swing-state advertising was especially effective, but none of this is dispositive.9

So, when you look at this chart, and you pick out the bluest states, you can kind of make a case that it’s a map of (some) swing states plus Utah, which kind of supports Yglesias’ theory that the Democratic ad war was highly effective.

On the other hand, when you look at this chart and you instead pick out the reddest states, the ones that shifted most toward Trump, you know what I see? It’s not a map of states with the lowest campaign activity, as Yglesias’ hypothesis suggests. It’s a map of Black and Hispanic people.

Baltimore, Chicago, New York City, and Newark are all key Black cities shown in red-shaded states on this map, while Texas, Florida, California, and Nevada (also shaded red) all have unusually large Hispanic populations. An alternative interpretation of the data, then, is that Democrats did a lot worse with Black and Hispanic voters than they expected, which hurt them less in swing states because there are fewer Black and Hispanic voters there.

This interpretation, too, has its odd points that don’t quite fit the narrative: Georgia and North Carolina are both heavily Black yet are bright blue here, and I don’t know what to make of that region around Connecticut.

I guess all I’m saying here is to approach the idea that “Harris’s ads and ground game were super-effective and were worth 2-3 points of margin” with healthy skepticism, at least until results are certified and the Pew study is out. It could be true that Harris’s campaign activity minimized the damage. It could also be true that Harris simply bled out more with non-Whites. Most likely, both theories have some truth to them.

The Glass is Three-Tenths Full

Abortion referenda won in seven out of ten states last Tuesday. Some abortion advocates are crowing about this, while some abortion opponents are despairing about it. “We won some, but we still lost most!”

This is the wrong way to look at it.

First, as I laid out in my “Election Preview: Abortion Edition,” winning three was very close to a best-case scenario for the pro-life movement. Relative to expectations, Tuesday was a smashing success. For the first time since Dobbs, we proved that we can win at the ballot box—with multiple strategies in multiple states under very different circumstances. (I’m eager to learn how South Dakota was able to muster a massive 60/40 majority to defend full fetal rights from conception, even in a bright red state, when Missouri was unable to fend off its attack.)

Second, this election is the first general election with pro-abortion ballot measures. Winning any states under these circumstances is a victory. Just ask the gay-marriage movement in 2004.

Third, five of these ballot measures had no practical effect. They passed in deep blue states where the right to abortion was already both unlimited and in absolutely no danger.10 Not a single child will die because those referenda passed. The referenda that mattered—the referenda that both sides invested in—were the referenda in the five red states: Florida, Missouri, Arizona, South Dakota, and Nebraska. We won three out of five. (Granted, these are red states, so they were on our turf.)

Fourth, this result, combined with the fact that Harris ran solidly on abortion and lost, means we may never have to hear the phrases “Roe, Roe, Roe Your Vote” or “Roevember is Coming” ever again. The tooth is pulled. The fever is broken. Abortion no longer guarantees a win in every election, and Democrats seem (provisionally) to be waking up to the argument I made a year ago: that opposing abortion does hurt Republicans, but not by as much as you might think. Early exits (which remain crappy, of course) suggest that Trump pulled almost even with Harris on “abortion trust,” and was down only four points on that by Election Day.

I’m even seeing chatter on places like Reddit where serious Democrats are suggesting that abortion ballot measures are bad for them. The argument goes that putting abortion on the ballot means that a pro-choicer can vote “Yes” with a clean conscience and then vote for the pro-life candidate for Senate because he’s good on immigration or whatever. Democrats want to win elections, so they don’t want to give you this option, at least not as long as abortion is an issue that advantages them. This could spell the end of using abortion referenda to drive turnout. Or it might not. Fingers crossed.

Lastly, did you notice how many people voting for pro-abortion ballot measures seemed to genuinely believe that abortion bans hindered medical treatment for miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy? If we can find a way to get the truth out, around the hostile media, we actually have plenty of room to grow on ballot measures.

Regardless, though, Tuesday was a fantastic result for pro-lifers. The glass is three-tenths full, not seven-tenths empty. Celebrate celebrate celebrate.

On that note, a fun little treat: we didn’t just turn aside Nebraska’s proposed abortion-on-demand amendment; we actually beat it by constitutionally abolishing late-term abortion in Nebraska. This was not a policy change, since second-trimester abortion was already illegal, but now it’s in the state constitution. That’s nice!

We have some tough years ahead, though. Donald Trump has made it clear that he considers the pro-life movement fully repaid for our votes because he appointed the justices who overturned Roe v. Wade. He will not willingly spend any more political capital on our behalf. At exactly the moment when we could perhaps most use a Reagan in office, communicating to the American people the importance of life and our ability to love unborn children without harming mothers, we have Trump, who had to be bullied into opposing Florida’s abortion-on-demand constitutional amendment. (His obvious sympathy with it is likely one reason why we nearly lost that one.) There might be a few things we can accomplish through this administration, particularly through lower-level appointments… but, in general, pro-lifers should count on the next administration for nothing except to stay out of our way. We may even have to fight them as the new administration tries to advance anti-fetal policies, especially on embryo-destructive forms of IVF. That’s still head-and-shoulders better than we would have gotten from Harris, but it also means we’ll be picking our battles and leaving a lot of pro-life policy on the table that might have sailed through a DeSantis, Haley, or Vance Administration.

If I turn out to be wrong about this (as I was wrong in 2016 about Trump’s judges), nobody will be happier than I.

The Emerging Trump Majority (on SCOTUS)

Trump’s victory, combined with a comfortable Republican margin in the Senate, makes further changes to the Supreme Court very likely. Republicans have 53 seats, which means they can confirm judges without the support of Senators Collins and Murkowski (both of whom support legal abortion and favor “moderate” judges).

First things first, if the Democrats are smart, they will bully Justice Sotomayor into retirement this week. However, we know the Democrats are not smart, because the time to bully Justice Sotomayor into retirement was last year. Nate Silver laid out the case in April:

He’s right: this is not a close call. If you are a progressive and you care about wielding power in the United States, you need to get Sotomayor off the Court now, while Joe Biden can still (probably) get her replacement through the Senate. The risk that she will otherwise die in office under a Republican President (or under a Democratic President + uncooperative Republican Senate) is very high. Democrats have a 50/50 shot at the presidency in 202811 and a substantially lower chance at taking the Senate. Conditional on the Democrats winning the presidency in 2028 without carrying the Senate, they are likely to lose ground in the midterms and give even more Senate seats to Republicans in 2030. I’d say the Democrats probably shouldn’t count on having the Presidency + Senate again until 2032, but it could easily be 2036 or 2040.12

In 2032, Justice Sotomayor, a diabetic whose father died of a heart attack at age 42, will be 78 years old. It is a terrible idea to commit herself to surviving that long in order to ensure another progressive replacement. Senate Democrats are understandably skittish about ramming through a replacement in just a few weeks before the new Republican Senate takes power. They are understandably nervous that, if they attempted this and failed, Trump would get a free vacancy to fill in a progressive SCOTUS seat. But come on, boys. Senate Republicans rammed through ACB’s nomination, soup to nuts, in 35 days flat, and they didn’t even skip all the skippable steps. (Confirmation hearings are actually optional!) You could do it. Burn all the political capital you need; there’s no elections for two years, the People have a short memory (for everything except inflation), and preserving a seat on the Supreme Court is worth almost any political sacrifice anyway.

While I’ve been typing this piece (Sunday night), CNN reported that Sotomayor is (through backchannels) refusing calls to retire. That’s great news—for me, a judicial conservative who loathes everything Justice Sotomayor stands for. There’s a good chance that she will not be able to continue in office all the way to the next Democratic presidency. Some back-of-the-envelope math suggests that she has about a 1-in-12 chance of simply dying during this presidential term, and nearly a 1-in-5 chance of dying before the end of the next. Other factors could compel her retirement. Either way, there’s a decent chance that a Republican replaces her with an originalist, making the originalist majority on the Court 7-2 instead of 6-3. I wouldn’t call that a likely outcome, but Sotomayor’s apparent arrogance opens up that chance for no good reason.

Meanwhile, on the conservative side, a healthy GOP majority means we should expect to see one of the older Republican-appointed justices retire in June 2025. If you can navigate Kalshi’s stupid wallet system (I can’t), there’s still money to be made betting on this.13

Justice Thomas the oldest justice on the Court, but the scuttlebutt I’ve picked up is that Justice Alito is likelier to be the first out the door. His wife clearly wants him to retire soon so that she can, inter alia, launch a campaign of full vexillological terrorism without having to worry about the effects on her husband’s career. I’m not sure Alito’s health is quite as good as Thomas’s. Moreover, I suspect that Alito views his majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson as his crowning achievement, and he is almost certainly correct. There’s no going up from there. Alito is also the second-most political judge on the Court, and one would expect a politically tuned-in judge to be especially nervous about pulling a Ginsburg.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had a golden opportunity to retire in June 2014, under a Democratic president and a Democratic Senate, but she stayed on. I read, long ago, that she was hoping that she could be replaced by the first female POTUS. (Counterpoint: the New York Times argues that RBG was afraid of making Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s mistake: retiring too early. This seems less arrogant and more forgivable.) Ginsburg then died in agony, desperately trying to stay alive and cover up the extent of her illness to the public as she fought a return of what turned out to be lethal pancreatic cancer. All she wanted was to survive until Joe Biden could win the election and replace her… but she didn’t make it. The cancer felled her six weeks from Election Day. Amy Coney Barrett was on the Court by the time polls closed… and ACB has undone much of RBG’s legacy.

Justice Alito had a front-row seat to her death throes, and likely saw a lot that will never be revealed to the public. The Nine keep their colleagues’ secrets. Yet, having seen Ginsburg go through that, Justice Alito will likely not want to find himself in a situation where he is desperately trying to stay alive long enough for a conservative to be elected so that he can safely die. I think Alito wants to enjoy a retirement, but he cares too much about conservative politics to risk retiring without a guaranteed conservative replacement. That means this, right now, is his golden window of opportunity.

Of course, if that’s true, the most political judge on the Court should feel the same, right? Yet the most political judge on the Court is Justice Sotomayor, who, as we’ve seen, is not having it.

Nevertheless, I expect Alito to announce his retirement at the end of June 2025.

Justice Thomas would be next up. I’m slightly less confident that Thomas will seek retirement. Unlike Alito, who could plausibly be replaced by any reasonably competent judge with a broadly partisan outlook, Thomas is a singular character in American judicial history. His seat will be filled, but he will never be replaced. His work is not yet finished; stare decisis still exists, and so does substantive due process. Yet Thomas has lived to triumph. In 1992, he was widely considered a right-wing extremist. He was the victim of plenty of racist epithets, and a softly bigoted news media often portrayed him as a mere lackey to Justice Scalia rather than an independent thinker. He dissented often and won rarely. In 2024, Justice Thomas’s brand of originalism is the leading theory of legal construction in U.S. courts, including the Supreme Court. His jurisprudence is now widely recognized as fiercely independent and remarkably convincing. Though Justice Roberts is technically Chief, Justice Thomas is the intellectual godfather of the Supreme Court’s majority. The media still covers him as a lackey—but a lackey to billionaires, since it is no longer plausible to call so formidable a justice a “lackey” to any other. Thomas still catches his share of racial epithets, too.

The work of originalism remains frustratingly incomplete—consider how the Court’s originalists fractured in the Rahimi gun-rights case this past term—but, on the other hand, it’s probably as complete as it’s ever going to be in Justice Thomas’s lifetime. He can now retire with a wreath on his head and garlands round his neck, or he can stay on the Court too long and gamble his whole legacy. He is healthy and seems to really enjoy the work, so I am a little more nervous about Thomas choosing this path than Alito. He spent many years as my favorite justice, but, if he decides to stay, I will join the efforts to bully him off. I do not share my fellow conservatives’ belief that treating the most powerful political body in our government as a political body is uncouth (although I understand it).

Of course, some of this hinges on Donald Trump. If one of the justices retires and Trump nominates a well-respected, vetted Federalist Society originalist, that will encourage the next justice to retire. If, on the other hand, Trump nominates a Harriet Miers-style debacle to the Supreme Court, that will discourage the next retirement. Trump is no longer running for re-election and we know that he will want loyalists on the Court. We know he is unhappy with how “his” nominees “treated” him after the 2020 election. We also know that the overwhelming weight of his incoming administration (and the Senate) will be backing traditional Federalist Society originalist types. It’s unclear, as yet, whether these two impulses can be married, and, if not, which will have the upper hand. (Remember that Trump made a list of judges in the 2016 and 2020 elections, and promised a list for 2024, but he never released one.) The names I have seen in circulation so far have been surprisingly—relievedly!—normal, but I don’t know whether those names are coming from Trump or are pressure on Trump.

If Trump, Alito, and Thomas handle this well, though, Trump will end his second term having appointed a majority of the current Supreme Court, five justices, a stunning achievement—with room for more in case of unexpected vacancies.

Imagine a Debate Stamping on a Congressman’s Face… Forever

This one’s short.

In my election preview, I said that 53 GOP Senators is not enough of a majority to put the filibuster in danger. I expect that the filibuster is safe for the next four years. There’s simply plenty of Senate Republicans who are both on the record as filibuster fans very recently, and who seem to genuinely believe it’s a good idea to give the minority a Senate veto. Some of them (SUSAN COLLINS) depend on the filibuster to dodge tough votes that would endanger their re-election campaigns.

The survival of the filibuster could be good for the Republic’s future, but could be bad for Donald Trump’s legislative agenda. The Republicans in Congress will be unable to move major legislation, even with a trifecta, because Democrats will oppose it. That will limit them to passing bills through budget reconciliation (which requires only 50 votes and which can be done only once per year). You can do a lot through reconciliation. Trump’s tax cuts were a reconciliation bill, as was Biden’s hodge-podge of inflation drivers that he gave the ill-fitting title of the “Inflation Reduction Act.” On the other hand, it’s very difficult to do many other things through reconciliation. The Republican effort to repeal and replace Obamacare in the first Trump term failed largely because the restrictions imposed by reconciliation made it impossible for the majority to make the necessary structural changes and compromises to get to a broadly acceptable bill. Trump’s desired immigration policies also seem to be a poor fit with the reconciliation process (which was designed for budget-balancing measures). Trump himself, dimly sensing all this, sometimes opposes the filibuster (but sometimes supports it).

Untitled President

We find ourselves in a historic position: the American people have elected a man to be President, but the Constitution bars that man from serving as President. This creates obvious legal difficulties.

In the classic legal text on this subject, Dan Gutman’s 1996 middle-grade novel, The Kid Who Ran For President, these difficulties are solved when…

[SPOILER ALERT!]

…the American people unite to amend the Constitution in order to ensure that their chosen President is qualified in time for Inauguration Day. That is unlikely to succeed in this case. No doubt young Judson Mason’s14 campaign manager would be delighted to learn that, in the Year of Our Lord 2024, the Supreme Court has effectively done away with enforcement for at least some constitutional qualifications provisions. Perhaps Judson could simply have become President without an amendment, on account of there being absolutely nobody with standing to stop him! That seems to be the world we’re living in now anyway!

I will, no doubt, have more to say about this. For the time being, I think I’ve decided this much: De Civitate ordinarily15 refers to sitting presidents as “President” when first introduced in an article. If Donald Trump is inaugurated in 2025, De Civitate will instead refer to him as “Mr. Trump,” or, possibly, in some cases, as “de facto President Trump.” Given the presence of an overwhelming prima facie case against him, and the absence of any binding adjudication to the contrary (by any branch), I will not be able to acknowledge him as President, because he won’t be President. (Per the Twentieth Amendment’s provisions on unqualified candidates, J.D. Vance should become President instead.) However, at the same time, I don’t want to turn every single post about the de facto President into a fight about his legitimacy. Calling him, “Mr. Trump” seems like a good way to avoid raising the point.

Prognosticators in the Stocks

For the most part, this was yet another pretty good election for polling and election models. My own election preview did okay: the map I gave as “most likely” did not win, but the map I gave as second most likely16 did win.

It was a weird election for models, because, in the end, all they were able to do was say, “It’s a tie! It could go either way!” This raised understandable questions about whether the models were adding any useful information. They were: it’s valuable to know with high confidence that it is actually a close race, so you don’t make tactical errors like Mitt Romney did at the end of the 2012 election because he (falsely) believed he was winning. They were also able to contribute to a deeper understanding of the race’s dynamics, picking up on things like the racial realignment years before the election, and in the face of strong denials from many interested parties. Lakshya Jain of Split-Ticket recently made a broader, insightful apologia for polls in this cycle.

The one thing pollsters and the models absolutely guaranteed with their cautious, anybody-could-win approach was that nobody, nobody could drag them after the election for being “wrong again.” Their pick couldn’t be wrong because, for the first time since election modeling began in 2008, none of the election modelers picked anyone.

Oh dear:

In 2016, I could understand this reaction. Hillary had a genuine lead. Trump was only a normal polling error behind her, but only a few brave commentators were saying so. When Trump won anyway, it was easy to understand why people were shocked and angry at pollsters: a mixture of very bad work by amateurish election modelers (most of whom went out of business after 2016) combined with very human difficulties grasping probabilities. “You said Trump wasn’t going to win!” “No, I said he had about a 1-in-4 chance of winning.” “BOO!”

Election modelers launched into eight years of trying to add context to probabilistic forecasts, from JHKForecasts’ “equivalent poker odds” feature to FiveThirtyEight using the entire above-the-fold space to show plausible maps of plausible outcomes. (Also the dot plots! I miss the dot plots!)

In 2024, though, we see that maybe people never actually had a problem understanding probabilities at all. The forecasters could not have been clearer: it’s a coin toss! Could go either way! Yet I’ve seen so many people who are furious with them.

Maybe people just hate the messenger. Maybe the messenger who warns of possible bad news always gets shot when the bad news arrives. Maybe humans never learn anything, even things we’ve learned so well that we’ve literally embedded the aphorism, “Don’t shoot the messenger” into our lexicon.

The Ones Who Were Really Wrong, Though

Some election prognosticators were wrong. It is much more understandable that they are getting blamed for being wrong. I’ll consider three: James Carville, J. Ann Selzer, and Allan Lichtman.

James Carville was popular on the Left in the waning days of the election because he went everywhere saying the same thing: “I’m certain Harris will win.” Podcasts, newspapers, cable TV, he was ubiquitous, and he sold a reassuring message built on his long and successful résumé.

There was really no excuse for listening to Carville. He’s a pundit, not a pollster. His claims weren’t backed by data but by his feelings in his bones or whatever, which contradicted much of the available data. If you are still listening to pundits in 2024, you’ve learned nothing since 2012, when Nate Silver decisively defeated Peggy Noonan. Perhaps you are a child and this was your first election, so you didn’t know to ignore pundits. In that case, this is a hard lesson, but it’s a lesson everybody learns eventually.

On the other hand, I listened to J. Ann Selzer. Selzer’s A+ shock poll of Iowa showed Harris winning the state by 4 points. This poll single-handedly shifted my view of the polls from “leaning Trump” to “no discernible lean.” That poll, plus Jon Ralston’s (in retrospect) inability to accept his own data, is why I ended up cautiously predicting a nailbiter instead of cautiously predicting the Trump polling error that actually showed up. As I explained at the time, Selzer had a mind-blowing track record of publishing apparent outliers that turned out to be right, and this one was at least plausible. The aggregators correctly loaded it into their models, where it (correctly) had only a small impact. After all, Selzer or not, it’s still just one poll. Throw it in the average. It tugged the Silver Bulletin forecast about 2% in Harris’s direction,17 which is huge for one poll, but is still just 2%.

Yet, by painting a plausible picture of a race that was going Harris’s way, in a way that confirmed all the priors of base Democrats (the Selzer poll showed Harris winning on the backs of older White women), the Selzer poll had a huge impact on The Vibes. Post-election, it’s become clearer to me that a big portion of the Democratic base was huffing hopium wherever they could find it, and Selzer was a major supplier in those final days. Rightly so! There was no single stronger piece of evidence that Harris was going to pull it off, perhaps decisively. Yet it’s too easy for a hopium-huffer to lose perspective and invest far too much in a single piece of evidence that might prove wrong.

This piece of evidence was wrong. Obviously. Selzer missed the result in Iowa. Trump didn’t lose by 4; he won by 13. That’s a miss of 17 points.

You should honor her for this, because, as I explained in the preview, it is very important that we honor pollsters who post apparent outliers. They are our only defense against the scourge of herding, which ravaged (e.g.) Wisconsin polling averages in this cycle. The sign of an honest pollster who’s going to give you more signal than noise is that she always publishes her results, even shocking ones. The laws of statistics demand that these results will sometimes be wrong. That’s the bargain we make when we ask pollsters to be honest with us. Since polls use a 95% confidence interval, even a perfectly-conducted poll with an ideal population is going to fall outside the margin of sampling error 5% of the time.

Brother, there’s no such thing as a perfectly-conducted poll with an ideal population.

As a result, there’s one of these every cycle. In 2020, the Washington Post, a great pollster, showed Biden winning Wisconsin by 17. (He tied.) The Selzer Poll isn’t even the worst miss of this cycle: the Dartmouth Poll showed Harris+28 in New Hampshire the week of the election. (She won by 3.) Dartmouth definitely needs to check their methodology, because they showed a similarly wrong result in October. Once can be random accident, but twice in the same direction with the same magnitude is a methodology error. Selzer had no such warning signs: Selzer’s September result, Trump+4, was within the margin of error of the likely truth at the time—Trump was probably winning the state by 9 or 10 in September.18 Selzer’s summer result, Trump+18, was probably spot-on at the time (this was before Biden dropped out) and caused appropriate tremors in the Biden camp. This November poll missed badly, but it was the only clear Selzer miss this cycle.

Still. Selzer missing by 17 didn’t just miss the 95% confidence interval. It missed the 99% confidence interval. It missed the 99.99% confidence interval. The odds of Selzer missing by this much from random sampling error alone is less than 1 in 10,000. Here’s my theory of what happened:

Selzer's methodology is random digit dialing without demographic weighting. This is a superior methodology to the polling methodologies mostly used today. RDD is better at detecting “signal” and giving true results. However, pollsters had a reason for abandoning it, and it wasn’t just that RDD is expensive. Pure RDD stopped working reliably in 2016, as response rates plunged and partisan differentials in those response rates opened up. However, RDD kept working in Iowa! (I've heard this attributed to Iowa's demographic simplicity—it's a bunch of White people—and high levels of institutional trust. Sounds plausible.) Since it's a better methodology, Selzer obviously wanted to keep using it as long as she could.

Alas, my best theory of the case is that she’s hit a wall here. Unweighted RDD no longer works in Iowa. I'm sure she'll conduct a thorough review, but I strongly suspect it's going to be time for her to update her methods. That probably means the Selzer poll won’t be quite as powerful as it was in its heyday, but polling is all about trade-offs, and her poll won’t continue to be useful at all if she can’t get it calibrated better next cycle.

On the whole, though, I remain very much pro-Selzer. She’s out there doing her best, she’s clearly nobody’s hack, and she’s given way too many great results for one (bad) miss to mar her sterling reputation.

On the other hand, we have Allan Lichtman, touting his “13 Keys to the White House.” Dr. Lichtman insisted all campaign that Harris “held” the majority of the “keys” and was guaranteed to win. When that didn’t happen, he blamed everyone but himself: “racism, sexism, homophobia,” the “Democratic Party,” and “misinformation.”

Lichtman was always a charlatan. No one should ever have paid him any attention. Lichtman’s keys were obviously subjective, and, even if they had been objective, they just as obviously could never give you 100% confidence in the winner of the White House. (65% confidence? Sure, maybe, as long as you had no other information at all about the election.) The moniker the news media gave him, the “Nostradamus of Elections,” was nuts.

The keys are essentially a fundamentals-only model, only super vague and massively oversimplified. Fundamentals-based modeling is useful! You should include fundamentals variables in a comprehensive election model! But even a good fundamentals-only model (and Lichtman's model was anything but good) only gets you so far, because elections are very complicated and voters have opinions. No fundamentals-only model, for example, has any way to deal with “oops one party nominated a crime-doer but the other nominated an 82-year-old man who just started drooling in a nationally televised debate.” Fundamentals deal with macro issues that set the national environment, but elections are determined by a mixture of those fundamentals plus more particular issues or unique events. For this reason, fundamentals modeling MUST be combined with polling to give you a true picture of the election (and the fundamentals need to gradually give way to polling in your weighting as polling goes up and the election draws near).

I could go on about how Lichtman’s bunch of subjective, binary keys are a lot worse than the numeric fundamentals variables used by, say, Silver Bulletin or FiveThirtyEight. For example, you need to be able to say not just "per capita income growth good!" or "per capita income growth bad!", like an on-off switch, but you need to be able to weight REALLY STRONG per capital income growth from merely acceptable per capita income growth.

However, if I start down this path, I'll drill into all 13 keys and be here all day. Point is, the keys absolutely could never have done what Lichtman claimed the keys could do, even if God Himself set the Fundamentally True Values for each of the keys. Lichtman must have known this.

A more concrete illustration: Lichtman has been pretending all this time that he's predicted a bunch of elections in a row, but that's not even true. Prior to the year 2000, Lichtman had not specified how his keys worked in a popular vote / electoral college split. He predicted Gore 2000. Gore won the popular vote but lost the electoral college. Lichtman then said that he was vindicated by 2000, because the keys could only predict the popular vote winner. As far as that goes, that makes sense: the keys all deal with national environment issues, not how specific states break, so, if they were ever going to work, it would only be for the national popular vote. Lichtman then spent the next 12 years flogging the keys as a popular-vote predictor. (Wikipedia lists sources for this.)

Then, in 2016, he predicted Trump. Trump won the electoral college but lost the popular vote. Lichtman turned on a dime and said that the keys only predicted the electoral college, not the popular vote. This forced him to retroactively claim that the keys had been wrong in 2000. But this doesn't make any sense at all. The factors that cause electoral college / popular vote divergence have nothing to do with the national environment or the 13 keys! There is no apparent causal connection between them!

Dude's been dining out on having "predicted Trump" ever since, but he did no such thing. Lichtman correctly predicted the 2004, 2008, 2012, and 2020 elections. That's 4 of the last 7, which is just what you would expect from someone whose methodology is very little better than a coin toss.

On top of all this, he was a huge pompous jerk about his keys, so one of the first places I went for schadenfreude the day after the election was the recording of his livestream where he watched it all fall apart.

An unbelievably credulous media, suckers for a cool story and (especially) for anyone who'd reassure them that Harris will win, routinely reported none of this. They just presented his claims uncritically (over and over and over again!) and called it a day. As a result, people got suckered into Lichtman's spiel without realizing that the whole psephological community only acknowledges Lichtman to make wisecracks about him.

If there's one thing about election prediction I hope everyone learns this week, it's never to listen to Allan Lichtman again.

That’s a good note to close on.

PROGRAMMING NOTES: With this article, I’ve published 59,580 words in the past 30 days (not counting the two articles I published last week that others wrote, but which also absorbed some hours of my time). That’s a successful NaNoWriMo but for blogging, plus 10,000 extra words, plus some comments. With the election over, I am therefore declaring a Well-Earned Break. That will give me some time to rest and you some time to catch up on any articles you might have missed in the blizzard of the past few weeks.

Paylisters, glory be upon all their houses, should expect something between now and December 14 (the day the electoral college votes). I am working on a couple of Short Reviews but, if none of them coalesces in time, I will at least have a Worthy Reads by then.

Of course, one never knows when breaking news or inspiration will strike, so I’m not swearing I won’t publish anything to the freelist. Just don’t count on anything.

I will presumably return in December with a piece on election certification, since the insurrectionist winning creates some interesting legal wrinkles.

UPDATE 2024 November 12: I corrected three typos and lightly rewrote the paragraph that begins, “On the other hand, when you look at this chart…” for clarity. November 18: found another typo.

I cheated a bit: Kari Lake ran for governor in 2022 and lost because she is a terrible candidate. The AZGOP ran her for Senate this year and she lost because she is a terrible candidate. In 2022, the AZGOP was running Blake Masters for Senate, who lost because he was a terrible candidate.

Kinda makes you think the Arizona Republican Party is tired of winning, eh?

Basically every Republican who could lose did lose in 2018, so there were very few vulnerable Republican senators for the Democrats to try to unseat, and several vulnerable red-state Democrats for Republicans to target. Then Joe Manchin (D-WV) retired and the Democrats were screwed.

Hovde (WI) and Rogers (MI) also appear to have been good candidates, a cut above what the GOP was running in the average 2022 battleground race. Oh, gosh, remember Herschel Walker?

Don’t beat him over the head with that, though; comparing the House and Presidential national popular vote is a bit apples-to-oranges.

When I made this claim on my Facebook wall, a debate ensued about what counted as “decisive.” We ended up splitting election results into six general categories:

Recount w/Result Uncertain: so close you genuinely are never REALLY certain who the voters chose. (Florida 2000)

Recount, Perfunctory: close enough to require an official recount, close enough therefore to whip up partisans into a froth that the election was stolen from them, but really it's pretty clear who won pretty quickly (2016/2020, arguably 2004)

Close Win: candidate wins by enough that the win is crystal clear to just about everyone -- but not much more (2024, 1992, arguably 2004)

Close-ish: candidate wins by a healthy margin (2012)

Landslide-ish: candidate wins by a bigger margin but not a landslide (2008, 1988)

Landslide: candidate wins by 10 points (1984, almost 1996, almost 1980)

I tend to apply “decisive” to Type 6, Type 5, sometimes Type 4, and then only in very specific contexts for Types 3, 2, and 1. However, it’s perfectly reasonable to use it for Type 3 as well, in which case 2024 was decisive.

Look at Wikipedia’s list of seats up for election and try to find four, count ‘em, four Republican-held seats the Democrats could pick up to take back Senate control—while simultaneously defending their seats in red Georgia and purple Michigan/Minnesota/New Hampshire.

Their path of least resistance is probably Maine —> North Carolina —> Ohio —> Texas? Montana? Alaska?? Hope for a surprise retirement??? These are options but they are bad, hard options for Democrats.

(OTOH, I bet Susan Collins retires this cycle, which will make things easier on the Dems.)

UPDATE: Just before this article went to press, Twitter lit up with rumors that Mr. Trump will tap Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) to lead the State Department. That will lead Gov. DeSantis to appoint Rubio’s replacement until a 2026 special election to serve out the remainder of Rubio’s term. Florida is another unlikely target for Democrats, but it’s probably (?) easier than Texas.

The other president to serve non-consecutive terms, Grover Cleveland, was president before the term limits amendment passed. He got primaried. (Well, not quite. There were no primaries in the 1890s, but his party booted him at the nomination stage.)

Yes, I am assuming that Trump will step aside at the end of his second term. He’s already broken the Constitution’s qualifications clauses once (Amdt XIV Sec 3), but I suspect that term limits are so clear-cut, and so ingrained in American political culture, that even Trump won’t seriously think to question them. Leastways I hope so, because there ain’t nothing I can do about Trump’s bad choices!

Full disclosure: I did see a map of New Jersey, which I can’t find now, which colored New Jersey’s counties by trend, and found that the part of the state within the Philly media market trended less red than the rest of the state. So perhaps the swing state theory can account for this.

UPDATE: Found it! It’s actually three maps, displayed in this tweet by @ECaliberSeven on November 10. Interestingly, while looking for this, I found a different map, by the same person, that I hadn’t seen before, which showed you can also make the case that New Jersey’s swing was race-related, not campaign-related! So Ethan C7 provides us with evidence for both sides of the argument here.

UPDATE 18 November 2024: I’ve been reminded that Nevada’s amendment hasn’t even technically passed yet, because constitutional amendments in Nevada need to be approved at two consecutive general elections to become law. This was only the first. This a good constitutional provision. This does not make me optimistic that we’re going to win in 2026.

You always say that the Presidential election is 50/50 four years out, at least when there’s no incumbent running.

This isn’t weird. In the twenty-first century so far, each American political party has won one trifecta per decade, although that pattern could break at any time.

I’d buy this market at anything less than 75 cents.

The most implausible part of The Kid Who Ran For President is that American’s would ever elect a president named “Judson.”

…and very inconsistently!

…or third-most-likely, depending how you want to score it. I treated the “Polls Missed Red” and “Polls Missed Blue” maps as tied.

I have to eyeball this from a chart, because the actual daily model update blurb seems to have been lost in the Wayback Machine outage of 2024, which is going to impact political historians for decades.

Standard reminder: the margin of error on a poll might be +3, but that applies to both candidates. Therefore, if you are looking at the margin between both candidates, you have to double your margin of error. A “Trump+4” poll with a published margin of error at +/- 3%, then, could mean anything from Trump+10 to Harris+2.

You may object: “but that means the error bars on individual polls are huuuuuge!” If that’s true, a single poll barely tells us anything! You'd be right! That's why we use polling averages!

So, now for my Supreme Court thoughts, so long they need to be its own comment. In truth I’ve been wanting to post a lot of these SOMEWHERE, so this is a bit therapeutic to get it all out there. Unfortunately, due to waiting so long, it’ll probably be seen by not many people. Oh well!

I seem to be in the minority, but I do not think Ginsburg was, as you claim, “desperately trying to stay alive and cover up the extent of her illness to the public as she fought a return of what turned out to be lethal pancreatic cancer. All she wanted was to survive until Joe Biden could win the election and replace her… but she didn’t make it.” I have no doubt that Ginsburg would have preferred that Biden replace her than Trump. However, I do not think she was simply trying to stay alive with that goal. Indeed, if that WAS the goal, some of her decisions do not make much sense, such as continuing to want to join deliberations and write opinions while she was recovering from illness. The smarter choice regarding health would be to skip out on those for a while.

Here’s my take: I think if Hillary had won, Ginsburg still wouldn’t have resigned. She would have kept going. She’s repeatedly said she would keep doing the job as long as she thought she could do it, and I believe her. Admittedly, in the alternate world where Hillary won, I think the Republicans (if they still held the Senate) would’ve relented and confirmed Garland, shifting the court to the left and meaning even if Ginsburg was replaced by Barrett it would’ve had a lesser impact. (also, Kennedy probably would’ve retired midway into Hillary’s term anyway; by all appearances he wasn’t retiring strategically, he just was tired of the job)

However, if I may opine, I do not think the justices think the way the public or politicians do. I’m sure all of them would prefer that a president of the same party as the one that appointed them would appoint their replacement, as that new person would be far more likely to rule in the same way they do. However, I don’t think that’s anyone’s main reason for their timing of retiring. I don’t think, regardless of the identity of the president, any of them have any interest in retiring if they they weren’t already at least considering it. As noted above, Kennedy by various indications was just tired of the job and probably didn’t care too much about who was president at the time. Breyer might have been considering politics more specifically, but he was old and probably was considering retiring anyway and all the people screaming at him to retire was, if it played any role, just the tipping point for something he was already thinking about. I don’t think Ginsburg had interest in retiring at all, she liked the job and wanted to keep doing it.

But maybe I’m just being naive. I’m trying to psychoanalyze the decisions of people I never even met. But I do legitimately believe that (had she lived longer) Ginsburg would’ve continued to stay on the court as long as she continued wanting to be on it, regardless of the president.

I do think Alito is the one most likely to retire. I don’t think it’s Dobbs as you say, but more him possibly just getting tired of being on the court, which there is some evidence may be the case.

Thomas has shown no indications of not liking being on the court. The flurry of concurring opinions rather shows he loves being on the Supreme Court, and why expend all that extra energy if he was staying around to avoid retiring under Biden? I think he will continue to be on the Supreme Court regardless of who the president is as long as he feels he can continue doing the job and wants to keep doing it.

In regards to your question of who could replace him… well, I don’t know too much about federal judges in general, but of the ones I know about, James Ho seems the closest thing. Much like Thomas, he seems very willing to reconsider just about every precedent in existence, even to extents I feel are way too extreme. Also, you get diversity points—actually, probably even better ones than Thomas. Thomas was the second African-American justice, but with Ho you not only get the first Asian-American justice, you also get the first immigrant justice. The big question is whether someone with a paper trail like his could get past the Senate.

Now, let’s talk Sotomayor. I feel much of your discussion ignores a rather critical point, which is that it seems to assume the Democrats ARE capable of forcing her through. What a lot of commentators seem to miss is that while the Democratic CAUCUS has 50 people, there are only 46 people in congress with the party affiliation of Democrat. We can bump it up to 47 if we count Sanders who quite frankly should just be honest and label himself a Democrat, but the other three are a different matter.

Angus King has clear Democratic leanings—hence him caucusing with them rather than the Republicans—but still is an actual Independent. Sinema swapped her affiliation to Independent which certainly shows a break with the Democrats—but that might have just been a gambit for re-election due to worries about getting primary’d, and when she realized she’d lose anyway, she just decided to not run for re-election. Manchin also went Independent despite there being no political advantage to; Sinema at least might have been trying (and ultimately failing) to play 4D Chess, but Manchin had already said he wasn’t running for re-election, and so there was no political advantage at all to him to break with the Democrats.

Why is this important? Because the only actual reason to replace Sotomayor right now is partisan politics, and because these three have (to varying degrees) distanced themselves from the Democrats, it becomes a very open question as to whether they would be interested in supporting this. Maybe the Democrats could still do it if they manage to pick up Collins or Murkowski? But that seems dubious also.

In regards to more general thoughts on the Supreme Court, despite them getting Trump v. United States very wrong, on the whole I’d definitely take current majority over it being the other way around (I’ll take Trump v. United States if it meant getting Dobbs v. Jackson). However…

Conservatives no doubt are happy about having more control of the Supreme Court, but it may be a pyrrhic victory indeed given the desire of various Democrats to try to pack it. Would they have done so if they had won this election? I am not sure; the fact it hasn’t been possible (no trifecta) has allowed a lot to stay quiet about it, and we might have found more resistance had Democrats been the winners. So maybe we wouldn’t have seen a push to stack the court. But if it ends up 7-2 instead of 6-3? That’s a whole different story! I think if that happens, that would absolutely give them the backing and incentive to bump the Supreme Court up to 15 people the next time they get the trifecta.

This is the danger I see to conservatives should Sotomayor die while Trump is president with a Republican-controlled Senate. That swaps it to 7-2, and at that point I think Democrats will probably go for broke next time they get a chance (unless the way it turns out is they get the presidency and Senate but no House, and then get to somehow replace a Republican-appointed judge with a Democratic-appointed one, returning it to 6-3). Too much control of the Supreme Court could end up backfiring for Republicans.

Of course, if the court returns to 5-4 that means it’s precariously close to one Republican-appointed justice dying at a random point and letting the Democrats swap it for themselves. Ironically, this is actually an argument often raised for increasing the size of the court, namely the fact so much changes politically just because someone happens to die at the wrong time; if Ginsburg lived a few more months, things would have been very different. This is really not the case for any other single position in government; maybe a death can flip a Senate seat, but the high number of people in the Senate helps mitigate their importance. If the President dies, they’ll be replaced with the (presumably) like-minded Vice President, unless we get another Lincoln-Johnson situation I suppose. The Supreme Court can change massively just by one random death. Think of what would’ve happened if the assassination attempt against Kavanaugh had worked.

In the end, despite all of this writing, I kind of look at it and still feel uncertain about a bunch of things. Maybe I just wanted to hear myself talk a bunch. Still, the takeaway is I do have some considerable worries about judicial conservatives ending up in a potentially pyrrhic victory if they win so much on the Supreme Court that Democrats decide to just pack the court themselves and undo all of that. Sure, they can’t do that for at least 4 years, but if we end up with a 7-2 court I think they’ll be going for it the next time they get a trifecta, which will inevitably happen.

And that’s the end of my somewhat stream of consciousness comment. (I had to cut it down a bit, actually)

I have a number of thoughts… but my bigger ones are on the Supreme Court and thus I will separate my comments so any discussion on that topic is not bogged down by the rest. Or at least that was the original reason... I then realized my Supreme Court thoughts were so long they couldn't even fit in their own comment, and I had to cut down on them. But that's the matter for the separate comment I'll leave.

So, first, regarding this:

“We find ourselves in a historic position: the American people have elected a man to be President, but the Constitution bars that man from serving as President. This creates obvious legal difficulties.”

I disagree with this on the grounds that I do not believe that the Constitution bars Trump from serving as President. I have read both the original article by Paulson and Baude arguing as such, as well as articles you have written on the subject, and I think they come up short. Your article “The President’s Insurrection” makes a reasonable case for Trump’s behavior on January 6 being disqualifying in the sense that, with or without a Fourteenth Amendment, someone shouldn’t be President if they behave in such a way, and was in fact part of the reason I declined to vote for him and voted third party. However, as a matter of proving that Trump is LITERALLY disqualified for office under the Constitution, I feel it (as well as the original Baude/Paulson article, I have not read their follow-up) comes up short in arguing that Trump was disqualified for engaging in insurrection.

Even if we were to accept the argument that Trump did in fact engage in insurrection (an argument I again am not convinced of, despite finding his actions very problematic) I also think that the argument that the President does not count as an officer of the United States is actually quite credible and that Trump is therefore exempt. Which actually makes your statement rather surprising to me; your article analyzing that question seemed like you considered this exemption for Trump to have at least some credibility. Perhaps since that article you have become more convinced that the President does qualify as an officer of the United States, but you seemed to believe it has at least some merit to it, so to see a flat declaration that “the Constitution bars that man from serving as President” was rather surprising.

But, my purpose here isn’t to try to convince you Trump isn’t disqualified; it’s pretty clear you’re not going to be dissuaded from that. The problem I have is you offer no qualifier of “my belief is” or anything like that, and instead assert it as definite fact (not just here either, in a separate footnote you declare without qualification “He’s already broken the Constitution’s qualifications clauses once”). Even if I did think Trump was disqualified, I would not assert such a thing as if it were some kind of hard fact, because quite frankly it isn’t. We’re not talking about something simple like age or number of terms served, but something far more blatantly subjective. This isn’t something like the natural born citizenship requirement where, even if there is some disagreement on exactly what a natural born citizen is, all of the definitions people have put forward are pretty objective if accepted. What I mean is, whether the definition is “anyone born as United States citizen” (the position I think easily has the strongest support; see, for example, Michael Ramsey’s “Originalism and Birthright Citizenship”) or the much more narrow definition of someone born in the United States of citizen parents, both are objective metrics and, so long as the circumstances of someone’s birth can be established, provide very objective criteria. That is not the case for the Disqualification Clause. The Constitution isn’t holy writ, there isn’t one “definite” correct interpretation of everything in it (the people who WROTE the thing disagreed on how to interpret it on some points). So I believe that even if I did think Trump was disqualified, I could only consider that to be my belief, not any kind of objective reality to be stated as fact.

Maybe the argument is to ignore theorycrafting and instead focus on the legal rulings involved; Roe v. Wade might have been blatantly wrong, but it was still the precedent held until it was overturned. So under that idea, one could try to say that the Colorado Supreme Court ruled against Trump and because the Supreme Court did not address the argument on insurrection but rather just said the Colorado Supreme Court couldn’t make the determination, that means Trump is legally barred under that precedent. This is problematic because the Supreme Court still said the Colorado Supreme Court couldn’t make the determination, thus nullifying the decision anyway (the SCOTUS’s opinion might have had problems, but it has rule of law for now). Even if we were to suppose the decision holds, the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision applies only to Colorado, which went to Harris anyway.

The final issue I have is that even if I were to grant everything, that Trump is undeniably and objectively disqualified from the presidency, he would still be president (assuming that the electors elect him and it is accepted by congress, which is almost certainly going to be the case). It might mean his position is against the constitution, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t have the position.

It is perhaps a bit ironic for me to write all of this text on the portion where you say you don’t want to make every post about Trump into an argument on the subject (“However, at the same time, I don’t want to turn every single post about the de facto President into a fight about his legitimacy”), especially when I consider that my biggest disagreement on it is not technically your belief, but the way you assert it as fact. But, well, I ended up writing all of this, so might as well keep it.

But to address what was the actual purpose of your remark, which was you saying you didn’t want to refer to him as President Trump and were planning on Mr. Trump… I would recommend just saying “Trump” or “Donald Trump.” “Mr. Trump” is awkward and feels unnatural. On the other hand, people say “Trump” by itself all the time and it looks perfectly natural.

Moving onto parts of less argumentation, a few other comments…

… hrm. Re-reading he post, I feel like (aside from the Supreme Court, which I’ll get to) I don’t have much to comment on, as I don’t think I have any real disagreements and in fact found out some interesting things I didn’t know about. If just a few sentences had been slightly adjusted, I could’ve saved myself all of these paragraphs.

However, one election that most people probably never heard of but was of great importance to me was Alaska’s referendum on ranked choice voting. In 2020, Alaska implemented by referendum a change to the way its elections worked. More specifically, the primary has as many people who want to run (allowing multiple per party) and then the top 4 vote getters progress to the general election, which is decided by ranked choice voting. This year there was a referendum to try to undo that referendum, but it failed in a very close vote (0.2%), so ranked choice will stay. Now, I don’t live in Alaska, but I think this was a very positive thing.

I’ll admit that, although I was a major proponent of it previously, I’ve cooled a bit on ranked choice voting. There are definitely some issues with it. Still, I think it’s (on the whole) a major improvement over our current system, along with this method of handling primaries. Some kind of reform is absolutely needed from our first-past-the-post system, and this was a step in the right direction. So it’s good we didn’t take a step back, and maybe we can see things like this spread to more states, which would have been harder if it was repealed.

I have become a bit more bullish on approval voting—that is, you don’t rank them, you just vote for as many candidates as you want, and whoever get the most votes wins. This of course solves the problem of vote splitting. While this doesn’t allow you to give preferential voting as you can with ranked choice, it does solve some of the issues with it; it’s easier to understand and also allows you to call races faster. Personally I don’t think having to wait is that big of an issue, but it’s still something that people complain about with RCV, as if someone doesn’t get an outright majority you need every vote to be counted before you can tabulate them to determine the winner. Approval voting allows instant results.

Regardless of whether ranked choice or approval or whatever else is better, they’re certainly better than what we have now, and the fact we haven’t taken a step back into first-past-the-post is to me a major victory.

I feel like there was something else I wanted to say, but this is long enough so I’ll close it here (separate Supreme Court comment incoming!)