The Impact of Dobbs on General Elections

Spoilers: I think it's about 1 point, give or take. That's real, but not decisive.

Research for this article cost $10, not something I would have done in pre-Substack days. This expense was made possible by Substack subscribers to De Civitate. Thanks, subscribers!

There is a lot of concern within the pro-life movement (and glee outside of it) that, after the fall of Roe v. Wade, supporting unborn rights has become an electoral albatross. Not only do pro-lifers fail to win ballot referenda in the Dobbs era, but also (the thinking goes) abortion is making it unreasonably difficult for Republicans to win in general. Uniformly pro-choice data journalists have done everything in their power to encourage this sense of panic.

It’s working. Just this week, I read an article by the wonderful Kathryn Jean Lopez in which she seemed to be trying to come to terms with this. She’s hardly alone. The idea that the country was not “ready” for Dobbs has only gained currency since I last wrote about it, and not without cause. It’s worth panicking about! If the pro-life party had to choose between being pro-life and winning elections, the pro-life movement would have no political future. So the stakes are high when we ask, is that true?

We cannot know the future, but we can know the past. Many people spout opinions about the political effect of abortion in future elections without making even a rudimentary attempt to show that abortion had any effect in the last election, the 2022 midterms.

This blogletter is my rudimentary attempt to show it and, to the extent possible, quantify it.

Victory by Gerrymander?

I was inspired to write this by a recent comment here at De Civitate, which argued, inter alia, that the Dobbs effect is fatal to Republicans, and the Republican “victory” in 2022 was actually a cheat:

The midterms would have been a blow out for the Democrats in the absence of gerrymanders, or if gerrymanders had been equally allowed. Without them, the Democrats would have a trifecta right now.

This is a common argument. Many intelligent and influential people, especially many Democrats, continue to believe that the only reason the Democrats lost the House of Representatives in the 2022 midterms was GOP gerrymandering. This is wrong, and it is obviously wrong as soon as you think carefully about what gerrymandering is.

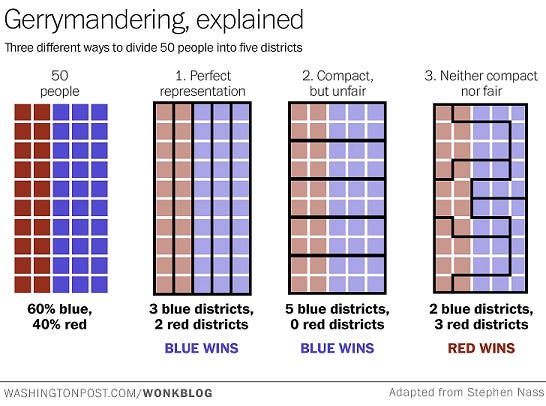

I’ve written a lot about gerrymandering, but, to recap, a gerrymander is when you carve up districts in funny ways to give disproportionate representation to one party. For example, suppose you have 1,000 voters. 600 are Red Party and 400 are Blue Party (a ratio of 3:2). You must assign those voters to 5 electoral districts with 200 voters each.

A perfectly proportional system1 will put all 600 Red Party voters into three districts and the remaining Blue Party voters into the other two districts, so the area overall ends up with 3 Red representatives and 2 Blue representatives (a ratio of 3:2). In a perfect gerrymander, you’d instead put 120 Red voters and 80 Blue voters into each of the five districts, resulting in 5 Red representatives and 0 Blue representatives—hardly fair!

Now, consider the 2022 midterm elections for U.S. House of Representatives. Excluding third parties, Republican candidates nationwide received 51.4% of the total popular vote. Democratic candidates accumulated 48.6%. In a perfectly proportional system, Republicans would have ended up with 223.6 total seats. In the actual 2022 midterms, Republicans ended up with… 222 total seats. That’s right: under a perfectly proportional two-party system, Republicans in 2022 would have ended up with 1-2 more seats than they did. It simply isn’t the case that they won because of gerrymanders.

To be clear, there was a ton of gerrymandering in 2022—absolutely, that happened—but both parties gerrymandered hard this cycle, and their efforts mostly (luckily) cancelled each other out. Republicans won the House because, among American voters at the 2022 midterm election, they were the more popular party.2

Two Underperforming Presidents

Still, Republicans had a lot of factors pressing in their favor: an unpopular president, high inflation, a challenging retreat from Afghanistan, and a lot of popular anger at institutions (and therefore incumbents). Republicans can brag that they won the very first post-Roe national election, but, under the circumstances, Republicans “should” have performed much better than they actually did. A rudimentary “fundamentals” model (which projects House results based on presidential approval, the economy, and no third thing) predicted Republicans would pick up about 44 seats, for a total of 256, implying that the GOP would win about 54-55% of the two-party popular vote.3 For several reasons, 256 seats and a 9-point blowout was a big stretch, even in this favorable environment,4 but still, Republicans really should have won the popular vote by 6 or 7 points. (They won by 7 in the 2010 wave.5) Instead, their victory margin was a little under 3 points.

Many reasonable people, Republicans and Democrats, believe this 3-to-4-point underperformance was almost entirely because of the Republicans’ pro-life stance on abortion. As that same De Civitate commenter put it, “Dobbs gets all the credit” for the GOP’s disappointing midterm.

“All” the credit seems a bit much.

Let’s consider a few districts where the GOP massively underperformed. In the next section, we’ll try and put some numbers on this, but, to begin, let’s just try and understand the narrative arc of how the Republicans fell short on November 8th.

Ohio’s 9th district was perhaps the dreariest race of the night for Republicans. Longtime safe-seat incumbent Marcy Kaptur, after redistricting, suddenly found herself in a district where Trump had narrowly beaten Biden. Even as a practiced incumbent, on a night when Republicans were winning by 6 or 7 points (as “red wave” prophets expected), Kaptur should have lost by a point or two. Instead, she won by 13, performing more than 15 points better than she “should” have. How did this happen?

Well, in the Republican primary, there were three candidates. Two of them, Craig Reidel and Theresa Gavarone, were experienced state representatives endorsed by the traditional broad range of fellow representatives, U.S. Congressmen, newspapers, and the like.

The third, J.R. Majewski, is described by Wikipedia as a “U.S. Air Force veteran and rapper,” with no apparent political experience or, indeed, talent. However, he was known locally for attending the January 6th protest in Washington, and for turning his entire front lawn into a Trump sign. Wikipedia lists only one endorsement for Majewski: Donald J. Trump, former president. Thanks to Trump’s endorsement, Majewski won the primary… then catastrophically blew the election. His failure, by itself, accounts for about one-seventieth of the Republicans’ “missing” national popular vote margin—which is pretty impressive for just one district.

Another big underperformance came in New Hampshire’s 1st District, where Democrats and Republicans are equally competitive. Sure, the Democrat (Chris Pappas) had the incumbency advantage, but Republicans shouldn’t have lost there by 8 whole points. At first glance, it doesn’t look like anything went wrong: multiple experienced candidates competed in the primary, racking up normal endorsements from lots of normal sources, and the eventual nominee (Karoline Leavitt) had a normal platform. Then you realize that Leavitt worked in the Trump White House, denied President Biden won in 2020, and ran on her support for the Trump agenda. That explains it!

The GOP lost a lot of the votes it “should” have earned even in races it won. In Colorado, Lauren Boebert, one of the least popular people the America First movement has put in Congress, threw away an R+7 solid red district, where she “should” have won by 13 points, and instead won by a humiliating 0.2%, the closest race in the country.

And so on. Are you seeing the common denominator? It isn’t abortion.

To be fair, America First candidates didn’t tank everywhere, and the GOP took hard losses even in some districts where President Trump’s fingerprints are absent. For example, in Minnesota-2 (incidentally my home district), Tyler Kistner ran a perfectly normal, perfectly competent campaign6 and still lost by 5 in a D+1 seat. That’s far from the worst GOP loss of the night, but it’s still 10 points worse than Kistner “should” have done in a red wave.

One might conceivably blame Kistner’s loss on bad coattails from the conspiracy-minded scumbag the GOP chose to run in the gubernatorial election, Mr. Scott Jensen.7 One might then point out that Jensen, an election denier, was aligned with the Trump faction of the party, which (whatever you personally might think about the 2020 election) was something 2022 voters hated. However, blaming Kistner’s loss on Trump would be a bit of a stretch.

We need not blame every loss on the former president. It’s enough to say that the GOP lost a lot of votes in a lot of districts because voters did not like Trump-aligned candidates, and the GOP nominated a bunch anyway.

Magnitude of the Trump Effect

One way to put numbers on this is to compare how “traditional” Republicans and “MAGA” Republicans ran in similar races. For instance, Georgia’s elections for governor and for U.S. Senate. Georgia has an “index” of R+3. (That is, Georgia is 3 points more Republican than the national average.) According to the fundamentals we discussed above, Republicans should have beaten their “indexes” by 6 or 7 points nationally. In Georgia, that means a Republican should have won by about 9 points.

In the gubernatorial election, Brian Kemp became well-known nationally for refusing pressure from then-President Trump to violate Georgia state law or endorse Trump’s attempted election theft.8 Kemp was also a pro-life champion who signed Georgia’s bill protecting unborn children with heartbeats (relentlessly referred to as a “six-week ban” by pro-choice propaganda). In the 2022 primary, Trump (crying “disloyalty!”) made Kemp a top target, recruited David Perdue to run against Kemp, and endorsed Perdue. Perdue lost, and Kemp went on to a 9-point general election victory over Democratic election denier Stacey Abrams… hitting his benchmark exactly.

Meanwhile, in the U.S. Senate election, Mr. Trump convinced his old friend Herschel Walker to move back to Georgia to run, promised he would be “unstoppable,” and endorsed him very early. Despite misgivings, the former GOP establishment decided to fall in line behind Trump on this one, and Mitch McConnell anointed Walker the Republican standard-bearer a month later.

Walker was a disaster, plagued from the outset by gaffes, scandals (including a horrifying abortion scandal), and general vapidity. Walker lost to a (deeply flawed) Democratic candidate by almost a full point—10 points below the benchmark.

In Georgia, then, we can measure a “Trump penalty” of about 10 points.

Georgia was particularly catastrophic, yet this disastrous pattern played out, with remarkable regularity, in battleground after battleground on Election Night ‘22. (Mr. Trump ran a carpetbagging Dr. Oz against a serious Democratic opponent in Pennsylvania! Of course he lost! The only faint hope Dr. Oz ever had was that voters would punish John Fetterman for having a stroke!) One attempt to measure the size of the Trump Effect found that, in races where Trump-aligned candidates had defeated a “traditional” candidate in a primary, the Trump penalty was just about 5 points. A separate attempt put the penalty at 7 points in the battleground races where the red wave broke.9

Now, the Trump penalty only directly applies in districts where Trumpy candidates got the GOP nomination. The Cook Political Report says that, when America First Republicans went up against Traditional Republicans in primaries, the America Firsters won 40% of the time. That suggests10 that the Trump penalty cost the GOP something like 5 points * 40% = 2 points overall.

So Trump-aligned candidates explain roughly 2 points out of the 3- or 4-point “missing” Republican points we’re looking for. That means there’s still room for hostility to the unborn to explain some of the results—but not a ton of room. This is going to get messy, but let’s take a look.

Disentangling the Data

In the “generic ballot poll,” pollsters ask voters which party they would prefer in Congress. It doesn’t ask about specific candidates or races. This is useful, because it measures national party sentiment independent of specific individual candidates and their baggage. A voter who might prefer Republicans in Congress in general might still vote for a Democrat if the specific Republican on his ballot is Lauren Boebert… and, indeed, the Trump Effect tells us that’s exactly what happened. The generic ballot poll helps us set aside those race-specific issues and see how political sentiment is shifting nationally.

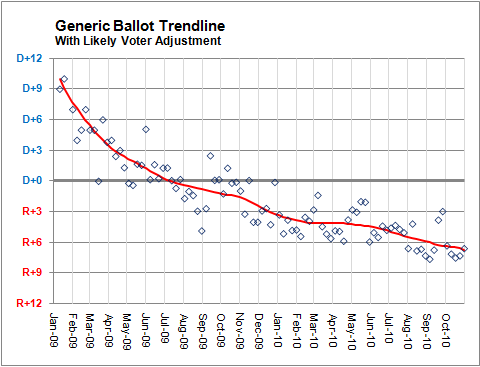

Here’s the 2010 generic ballot average calculated by Nate Silver at FiveThirtyEight:

In particular, notice how the trendline moved from the end of June 2010 onward. Between President Obama’s inauguration in January 2009 and the end of June 2010, Republicans added about 15 points of support, setting the stage for their fall victory. But the last four months of the campaign still mattered. Republicans added about 1.5 to 2 more points between the end of June and Election Day.

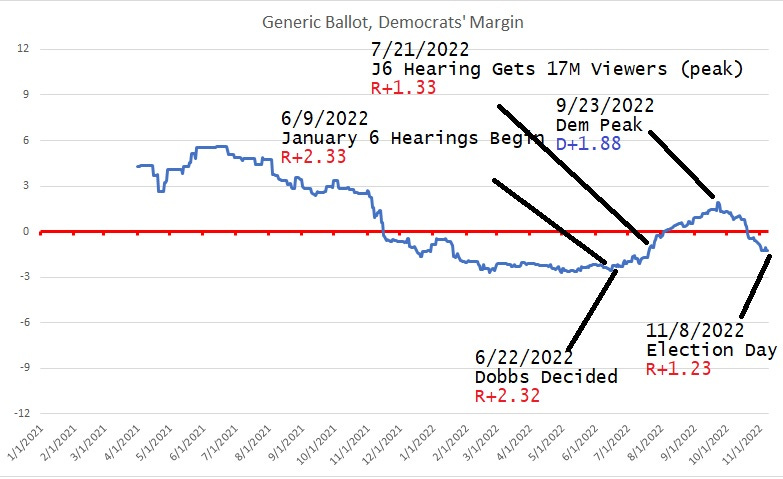

By contrast, look at the generic ballot in 2022:

Again, don’t worry so much about the numbers at any specific date;11 pay attention to how the numbers moved. Until June, the 2022 chart resembles the 2010 chart. In both years, after the president was inaugurated, his approval rating declined somewhat, which pulled Democratic support down with it, which set Republicans up for a midterm victory.

Then, there’s a divergence: in 2010, Republicans gained about 2 points on the generic ballot during the final four months of the campaign. In 2022, they lost 1 point in the final months. At certain times in the fall, it was even worse than that. Peak-to-trough, the Republicans lost 4.2 points in the 106 days after the January 6th hearings opened. (Dobbs happened on Day 13.) That’s almost as large as the hit the Democrats took on the generic ballot when inflation set in during Winter 2021-22, and slightly larger than the hit the Democrats took over the Afghanistan withdrawal.

Importantly, insofar as the J6 hearings (and I’ll count the Mar-a-Lago raid as part of that) impacted the Republican score on the generic ballot, a national measurement, this was not simply part of the “Trump effect” that we measured above. The Trump Effect measured the district-specific impact of running MAGA Republicans versus traditional Republicans. By contrast, the generic ballot shows how all Republicans were having their brand poisoned nationally. Despite some overlap, the national J6 backlash against all Republicans comes largely in addition to the per-district backlash against America First Republicans.12

To understand how this works, think of it as “splash damage.” It’s easy to recognize cases where America First candidates at the top of the ticket harmed downballot candidates. I’ve already mentioned the impact Trump-aligned Scott Jensen seems to have had on Minnesota’s downballot races, but it’s easy to look across the Great Lakes at Michigan’s Tudor Dixon or Pennsylvania’s double-MAGA billing of Dr. Oz and Doug Mastriano to see similar effects. Republicans lost control of the state legislature in all three states, despite winning the national popular vote. That’s almost unheard of under national conditions like these. The only other state where Republicans lost control of a state legislative chamber was Alaska—where the top-of-the-ticket statewide Republican candidate, Steve Begich, was hounded by Trump’s pick, Sarah Palin.13 It’s easy to imagine voters watching the Mar-a-Lago raid and souring not just on specific America First Republicans on their ballot, but the entire Republican enterprise. The result: backlash on the generic ballot.

Similarly, it’s easy to imagine voters watching Justice Alito righteously strike down Roe and souring not just on Sam Alito, but on the entire Republican apparatus that installed him and his fellow majority justices. Result: also backlash.

Fortunately for Republicans, this particular backlash faded a little down the home stretch, and the GOP ended up down “only” 1 point between June and Election Day. Unfortunately for Republicans, instead of adding to their advantage in the final favorable months before the election, they’d lost ground. In those final months, they did 3 points worse than they’d done in 2010. You might say that the difference between the Red Wave of 2010 and the red ripple of 2022 was the final four months.

Unfortunately for us, it’s really hard to look at this and disentangle the “national impact of Dobbs” from the “national impact of the January 6th hearings.” Some of it’s gotta be Dobbs, right? But how much?

If we had no other information, we could just split the blame in half. We might say, with low confidence, that the January 6th hearings cost the GOP 1.5 points, and Dobbs cost the GOP the other 1.5 points. However, we do have some other information.

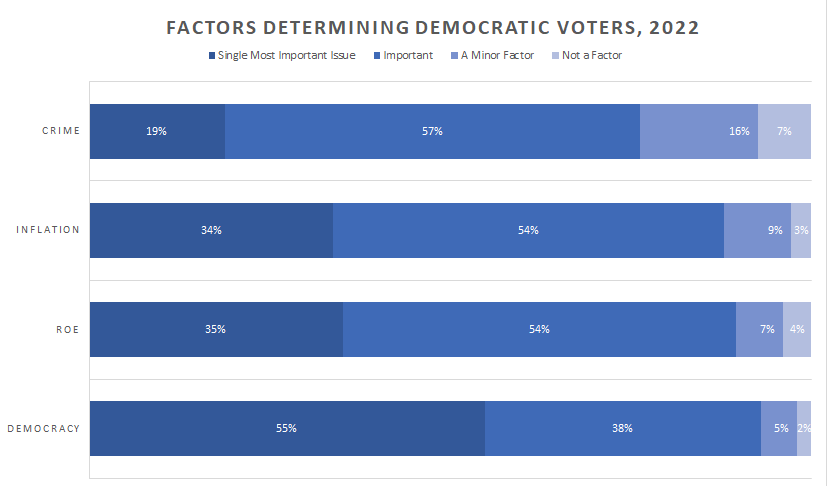

The AP-NORC did a massive exit poll during the 2022 midterm, and it asked voters which single issue (of four) was the most important factor in determining their vote. I grabbed the file. One of the factors the exit poll listed was the fall of Roe. Another was “the future of democracy in America.” I looked at how Democratic14 voters weighed the four factors, and here was the result:15

In this AP exit poll, the threat to democracy highlighted by the J6 hearings was the “most important factor” for many more Democratic voters than the threat to abortion highlighted by the fall of Roe—about 1.6 times more. If we use that to divvy up the blame for our 3-point vote gap, the J6 hearings were responsible for 1.8 points of the GOP’s fall slide and Dobbs was responsible for 1.2 points… give or take.

Republican Abortion Moderates Did A Tad Better

Let’s try to double-check this by looking at individual candidates.

Thanks to The Cut, I was able to locate 8 Republicans who ran for Congress as abortion moderates16 in competitive districts in 2022. Perhaps there were other abortion moderates out there, but I could not find a comprehensive list. Since The Cut focused on the competitive races where the red wave fell shortest, analyzing these 8 races will still be informative, if incomplete. These 8 abortion moderates ran in 6 different states, which helps—the sample is small, but at least it’s diverse.

Overall, Republican candidates in the 2022 midterms overperformed their indexes by 3.1 points, on average. That makes sense, since Republicans also won the popular vote by about that much. However, the 8 abortion moderates underperformed their indexes by -0.3 points. If we just took these numbers and went with them, we might conclude that running as a pro-lifer was actually an advantage in the 2022 midterms.

However, just taking the simple average is very unfair to Republican abortion moderates. First, the pro-choice side is hurt by the fact that incumbents tended to overperform—and not one of the abortion moderates were incumbents! The House just didn’t have abortion moderates in 2021, on either side. Second, all the abortion moderates were running in competitive districts, where, partially for demographic reasons (not just for Trump reasons), Republicans struggled to run up the score. Third, the simple average also underestimates the pro-life positions, because America First candidates tended to underperform—and pro-life Republicans were much more likely to be America Firsters than abortion moderates were.

I can control for this by limiting my analysis to non-incumbent, traditional Republican candidates in competitive districts17 who defeated America First candidates in their primaries. Adding those restrictions gives me 16 pro-lifers18 and 8 moderates. The moderates (still) underperformed by -0.3 points.19 The pro-lifers underperformed by -0.9 points. This suggests that, all else being equal, a Republican candidate in the 2022 midterms who stood by her pro-life stance lost about 0.6 points off her margin as a result.

Meanwhile, in the Democratic Party, the last pro-life Democrat, Rep. Henry Cuellar, beat his index by 10.3 points in a competitive district. Incumbent Democrats in competitive districts beat their indexes by, on average, only 6.9 points. One should not overread a sample size of one, and there’s lots of things that make Cuellar distinctive aside from his pro-life stance… but the only pro-life Democrat did 3.4 points better than his pro-choice peers. Interesting.

I also find it interesting (but, again, sample size insufficient) to note that the three Republicans who ran for U.S. Senate as pro-choicers (Lisa Murkowski of Alaska,20 Tiffany Smiley of Washington, and Joe O’Dea of Colorado21) performed substantially worse than their peers, even their Trump-aligned peers. Joe O’Dea missed his index by 10.6 points, the worst in any competitive race—worse, even, than Don Bolduc, widely seen as the most out-of-place MAGA candidate in the country (running in New Hampshire). No matter how you slice the data, Republican pro-choicers running for Senate did worse than the pro-lifers:

Overall, the average GOP Senate candidate overperformed by 2.1 points. The average pro-choicer underperformed by -5.8 points, implying an 8-point advantage for pro-lifers.

Restrict this to non-incumbents, and the pro-lifers underperformed by -4.2 points, but pro-choicers by -8.3 points. implying a 4-point advantage for pro-lifers.

Restricting to competitive races makes no difference.

In the Senate, pro-lifers outperformed pro-choicers even though most of the pro-life Senate Republican candidates were also America-Firsters, and thus were also held back by the MAGA headwinds we’ve already discussed. As with Cuellar, the sample size (3 Republicans, only 1 of whom was incumbent) is too small to draw conclusions, but, again, it’s very interesting that Republican Senate pro-lifers did better than similarly situated pro-choicers.

Mixed Evidence from State-Level Policy

We can also hunt for an abortion backlash against Republicans by considering states where “abortion was on the ballot.” Five states in the 2022 midterms had ballot referenda on abortion.22 Another nine states passed significant abortion restrictions in 2022, ranging from parental notification to full protection-from-conception laws.23 Moreover, at the time of the midterms, some twenty-three states had either protection-from-conception or heartbeat laws on the books, and, thanks to Dobbs, those laws had suddenly come into force, or imminently would be.

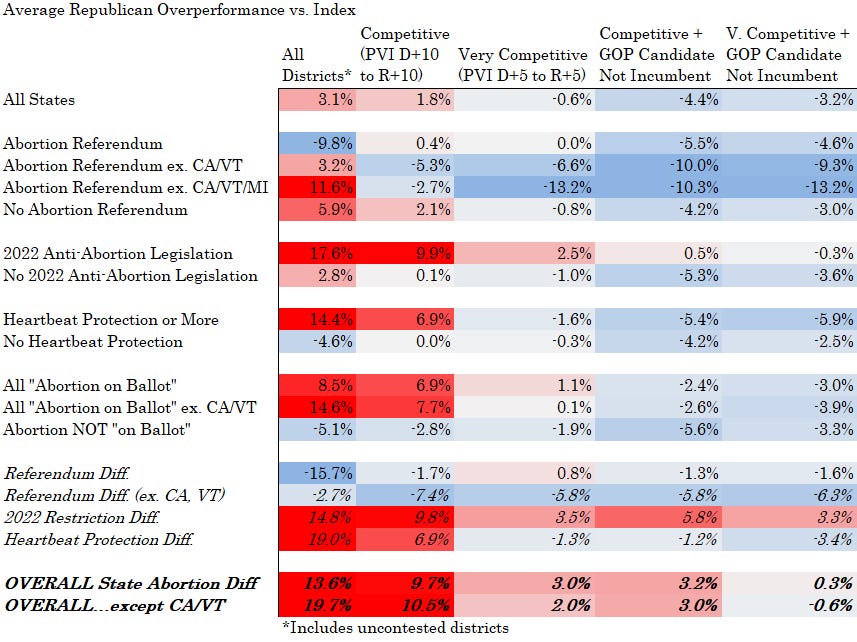

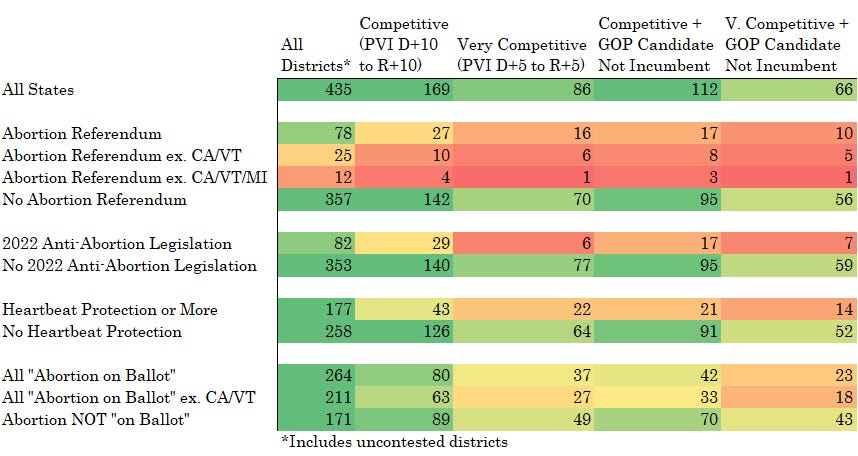

If there was a backlash in favor of abortion rights, we would expect that, in competitive districts where “abortion was on the ballot,” Republicans would have performed worse than they did elsewhere. But, when we do the numbers, it isn’t quite that simple:

In states where abortion was, in some sense, “on the ballot,” Republican candidates consistently did better than they did in states where it wasn’t! This remains true (barely) even if you only look at the toughest races, the very competitive seats where the Republican candidate was not the incumbent. (That’s the rightmost column, specifically the +0.3% cell, second from the bottom.)

In fact, in those same very tough races, we see Republicans being rewarded, not penalized, for being in states that passed abortion restrictions in 2022, to the princely sum of 3.3 points! What?!

On the other hand, still looking at the toughest races, it looks like abortion referenda did harm Republican candidates (-1.6 points), especially in states where there was a serious possibility of fetal rights being enacted (-6.3 points!). That tracks much better with the narrative that abortion was a huge albatross for Republicans.

On the other other hand, the toughest races weren’t that common, so that rightmost column has some very small sample sizes.24 That “-6.3 points” figure is based on only 5 districts, and 4 of them were in Michigan. As we discussed earlier in this article, Michigan Republicans had other serious problems, several of them Trump-related, which may be skewing this sample against pro-lifers.

On the other other other hand, when we said that Republicans were rewarded for passing abortion restrictions? That was based on just 7 districts, and the positive result was driven disproportionately by 3 districts in Florida, where Ron DeSantis largely avoided Trump traps and created a true red wave.

In short, it’s not easy to draw conclusions from these data, especially once you take sample size and homogeneity into account. At least, it isn’t obvious to me, when I look at this chart, whether abortion salience helped or hurt Republican House candidates in affected districts.

If you want to make the case that it hurt, you’ll focus on the ballot referenda. I think there’s a reasonable case to made for that. Outside deep blue states, there were only 10 competitive districts with referenda, but they were in 4 different states, and Democrats outperformed in those districts no matter how you slice the data, in some cases by ridiculous margins.25 That’s not enough evidence to confidently assert that abortion referenda destroy Republican candidates, but it is enough to assert that maybe they do. If I were a Democrat who didn’t care about abortion, I would definitely put resources into putting more abortion referenda on more ballots in redder states, in hopes of dragging down Republican candidates. (And the Democrats are doing exactly that!)

Meanwhile, if you want to make the case that anti-abortion state policy helped Republican House candidates, you’ll focus on the overall picture of states where abortion was, in some sense, “on the ballot.” We have pretty sizable samples there, from a pretty diverse cross-section of the nation, and Republicans in these districts did (relatively) quite well. Seats like Texas-15 are huge success stories for the GOP. Pro-lifer Monica de la Cruz not only ran in a state where abortion had been a top issue since the passage the SB8 “bounty hunter” law, and which had recently outlawed all abortions… but she crushed her incumbent opponent by 9 points to become the first Republican in history to represent this overwhelmingly Hispanic district. This sort of thing happened a lot more frequently than apparent abortion backlashes, even taking the referenda districts into account.

On the other hand, when some data are telling you that abortion is very bad for Republicans, and other data are telling you that abortion is actually kinda good for Republicans, it seems safest to split the difference and conclude: abortion is most likely kinda bad for Republicans. We see support for that, too: several cells in this chart show abortion hurting Republicans in affected districts somewhere between -0.6 points and 1.6 points, which is consistent with what we have found in the other data26 we’ve looked at.

So What Have We Learnt Today?

By looking at the generic ballot and AP-NORC exit poll data, we estimated that Dobbs was responsible for shaving 1.2 points off the GOP margin. By comparing individual races where Republicans ran abortion moderates, we estimated that pro-life stances cost Republicans on average 0.6 points (once we screened out the Trump Effect). We also found a couple of places (the U.S. Senate, Democratic House races) where being pro-life appeared to be an advantage, but the sample size was too small to draw a conclusion.

When we turned to state-level policy, we found mixed results. Slicing the state data in some ways makes it look like abortion was a very big help for Democrats. Slicing it in other ways makes it look like abortion actually helped Republicans. If we try to account for all that data (instead of disparaging some of it), we split the difference, and end up with figures that fit together nicely with an “abortion penalty” within the 0.6-1.5 point range we’ve been talking about.

On their own, these are all (to say the least) very uncertain measures. Taken together, I’m encouraged that they seem to be saying the same thing: Dobbs and Republicans’ pro-life abortion stance is probably responsible for the GOP losing about 1 point (more or less) of the 3 to 4 points it was “missing” in the 2022 midterms.

To put that in perspective: just 6 GOP House candidates lost by a margin of less than 1.5 points, and only 1 Senate candidate (Nevada). If we assume that moderating on abortion would have uniformly added 1 point to the GOP margin in every race,27 it would not have turned 2022 into a red wave, or even given Republicans control of the Senate.

This fits together with our data about the Trump Effect. Again, Republicans “should” have won the national popular vote by 3 or 4 more points than they actually did. If Republican support for the unborn is responsible for 1 point of that (or so), while individual America First candidates for 2 points of that (or so), and a broad backlash against Trumpism caused by the January 6th hearings is responsible for another 1 or 2 points (or so), then adding these three factors together explains why 2022 looked like a skin-of-their-teeth victory for Republicans rather than a 2010-style triumph.

To put that in perspective, cancelling the district-specific and national “Trump effects” in competitive races would have easily delivered the Senate, perhaps by a wide margin. Mark Brnovich would likely have won in Arizona; McCormick or Barnette in Pennsylvania; it seems almost anyone other than Herschel Walker would have won Georgia; Hassan in New Hampshire could have been seriously threatened.

Don’t marry this analysis. There’s a lot of numbers here, and God knows I spent long enough analyzing them, but there’s also a lot of proxies, assumptions, and educated guesswork in the mortar. There are several places where it could be wrong.28

On the other hand, I think this analysis does put some useful limits on how much abortion can be blamed for GOP fortunes in the 2022 midterms. Even if you challenge a lot of my assumptions, I think you’d be hard-pressed to say make a case that abortion policy cost the Republicans more than 2 points off their national margin in 2022. I think you’d be very hard-pressed to argue that abortion policy cost Republicans more than national Trump fatigue.

On the other hand, in an article I wrote before Dobbs entitled “Dobbs and Zeynep’s Law,” I argued that a pro-life abortion policy might actually help Republicans in the 2022 midterms. There are some promising signs in some data that this might actually have been true in at least some places, but the more reliable signs (in my opinion) point the other direction. I no longer believe abortion policy positively helped Republicans in the 2022 midterms. Abortion popped up in too many surveys in too many negative ways for me to believe it didn’t hurt Republicans at the margin.

Paying for Policy

Of course, all parties pay for policy. Being in power is a tough proposition for politicians: if you don’t keep your promises, your supporters get frustrated at you and kill you slowly. If you do keep your promises, your supporters are satisfied and disengage from politics, but your opponents get energized and kill you right quick. This is called the thermostatic model of public opinion, but all that means is that, when either political party scores a major policy victory, they lose public support. The effect is temporary, but “temporary” can mean months or years, depending.

It seems clear in the 2010 generic ballot chart (above) that Democrats paid a price for Obamacare, which was proposed and enacted between September 2009 and March 2010 (during which time Democrats lost 3 points). This albatross weighed on Democrats for years.

We can also see, in the 2018 generic ballot chart, that President Trump’s signature legislative achievement, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (proposed and enacted in November / December 2017) cost Republicans probably around 2 points. This time, the impact faded somewhat. Although Republicans that fall still suffered the worst mid-term defeat since 1986, this can mostly be chalked up to factors other than the tax cuts. (Namely, then-President Trump himself.)

Dobbs was a legal victory for the Constitution and a moral victory for vulnerable children, but voters interpreted it as a policy victory for the Republican Party, and you can understand why. Republicans then paid for it, to the tune of probably around 1 point in 2022. Such is politics.

This is worth remembering. When a Republican tells you that the party cannot “afford” to continue championing the rights of the unborn, he’s not telling you anything about the state of the electorate. He’s just telling you that he’d rather spend 2 points of Republican margin on deficit-expanding tax cuts than spend 1 point on defending the rights of children.

I’ve been wearing the green eyeshades throughout this post, but let me take them off for a minute to point out that fetal-protection laws across the country are directly responsible for saving some 25,000 children from violent death (at minimum!)—in just their first year of operation! Go ahead and think of another American policy that saves 25,000 children per year. I’ll wait.

Even with painful implementation hiccups (and downright failures), this is probably the best thing America has ever done, and certainly the best thing it has done in my lifetime. And all it cost was a 1-point hit? Barack Obama would have sacrificed a goat on live television if he could have taken only a 1-point hit from Obamacare, which saved far, far fewer lives (of much, much older people).

At any rate, people making the argument against Dobbs rarely consider that losing Dobbs would have come with costs of its own. Fiscally liberal pro-lifers who vote Republican because of abortion would have lost faith and stopped voting for Republicans. Fortunately, we will never have the opportunity to measure how big a drag this would have been, but it seems fair to say that Republican electoral fortunes would have been only a little better, at best, in a world where Dobbs had come out the other way.

On the other hand, a word of caution to pro-lifers: as I said, thermostatic public reactions are temporary. Since the cost of pro-life policy in 2022 was already relatively small, pro-lifers might be hoping that the cost will be wiped out in 2024. That is possible. However, by returning abortion to the states, Dobbs makes abortion an ongoing issue in many states. Rather than fading the way tax cuts and even Obamacare eventually faded from public attention, abortion has a way of staying in the forefront of the public mind, much like slavery. This makes it more likely that the abortion penalty, small as it is, may last for a while. It would probably be wise for Republicans to “budget” a 1-point headwind in 2024 based on abortion.

If Republicans would like to neutralize this headwind, they might consider ending other unpopular Republican policies, such as opposition to net neutrality; commitment to tax cuts on high-income earners and corporations; and free trade agreements… rather than leaving unborn children to die. The Wall Street Journal editorial board would sooner slit their own throats than make that trade, but again, that simply reveals that they place a low priority on protecting the unborn, not that protecting the unborn is somehow uniquely toxic to the GOP brand.

However, for many reasons, making these trade-offs is unappealing. (One of those reasons is that some of those policies are good ideas! The corporate income tax should be eliminated!) Fortunately, we can avoid making any of those trade-offs by simply jettisoning the most unpopular Republican policy: President Trump.

Looking Ahead

That comment which prompted me to write this article said:

At this point I think it entirely likely that the Democrats hold the Presidency, and take back the house by a healthy margin in 24. I think there is a good possibility they hold the Senate even though that path is hard for them, and Dobbs gets all of the credit. -John13

I think the lesson of 2022 is something like this: The Republican Party has enough popular support to be able to “pay” for some policies with a few points from its margins and still win. For many years, opposing abortion was, more or less, a cost-free benefit for Republican candidates. It isn’t cost-free anymore, but neither is it particularly expensive compared to other major GOP policies.

However, the one thing that the Republican Party really can’t afford, electorally speaking, is to remain the party that says Joe Biden didn’t really win the 2020 election (even if he didn’t, the country wants to move on), the party that nominates goof-offs like Herschel Walker and Dr. Oz (Dr. Oz!) to critical seats, and the party of January 6th.

In short, the Republican Party cannot afford to remain the party of Donald Trump.

Being the Trump Party is electorally expensive. Trump has never won a popular majority, and no one outside the QAnon faith seriously believes he ever will. He won the first time by a minor miracle of the electoral college (while losing the popular vote), then went on to suffer the biggest midterm election defeat since 1986. After that, Trump became the first incumbent president to lose the popular vote since Jimmy Carter George H.W. Bush.29 Because the electoral college miracle didn’t save him from his own unpopularity a second time, President Trump ended up losing to a senile serial liar named Joe Biden, leaving many people astonished that a loser like Biden could possibly win 80 million votes. (Explanation: Biden can only do that if his opponent is Donald J. Trump.) In the 2022 midterms, it seems that Mr. Trump and related antics cost Republicans somewhere between 2 and 3 points, making him the first President in history to lose a midterm for his party after he left office.

And what policy are we buying with all this wasted margin? He’s far more expensive than any individual policy, from free trade agreements to heartbeat protection bills, and yet there’s nothing Donald Trump would do in a second term as president (nothing conservative, anyway) that Ron DeSantis or Tim Scott wouldn’t do just as well or better.

Some readers may accuse me of bias, because (I concede) I have never been a fan of President Trump or of Trumpism. I am happy to admit that he was a much better president than I expected, and that he accomplished a number of very good things—including, directly, Dobbs itself. I was wrong about him in several ways (and right about him in several others).

However, even if you are a full-throated, no-holds-barred lover of Trump and his administration, you have to admit what the data is screaming at us: even if Trump is objectively perfect, too many Americans find him repulsive (fairly or unfairly) for him to be an effective standard-bearer going forward. He might possibly win in 2024 if Biden is weak enough, but his road to victory is much, much harder than the road would be for an alternative candidate, be it DeSantis, Scott, or one of the other proven conservatives running. I won’t make any further arguments against Mr. Trump here. All I’m saying is that, fairly or unfairly, he is very unpopular. Please, if you care about conservative victories, do not support Mr. Trump in the upcoming primaries.

I agree with John13 that there’s a good chance the Democrats will win back the White House and the House and even defeat their daunting Senate map in 2024. Furthermore, I agree that abortion is likely to play a small role in that drama, removing a point or so from the GOP margin. (Maybe less, if the thermostatic reaction fades a little more.) That could be crucial if the election is very close.

Yet I don’t think abortion will actually make a big practical difference in 2024. Assuming a weak candidate like Biden is the Democratic nominee, the economy remains fragile, and the GOP doesn’t nominate Donald Trump and his circus to all the key seats, taking back at least the Senate and holding the House ought to be a cakewalk, accomplished with plenty of margin to spare. (Running against a White House incumbent is always dicey.)

The problem is, I think there’s a very good chance the GOP will do exactly that—again.30 Then it may very well lose. I don’t think a reasonable person will be able to blame Dobbs—but a lot of unborn children might die because of our Trumpian arrogance.

In future installment(s), I’ll take a look at the much worse performance of pro-lifers in state-level ballot referenda, the human face of the movement, and I might even get around to scoring my predictions from the original article.

The main data used for this post is in Google Sheets, so, if you wanna Reinhart-Rogoff me, have at it.

For reasons beyond the scope of this article, perfectly proportional partisan electoral outcomes are neither possible nor desirable. Don’t walk away from this post thinking that James’s real point is that we should adopt a proportional parliamentary system with ranked-choice party lists! I don’t think that!

However, the “ideal” of what a perfectly proportional system would look like is useful. While some deviation is inevitable and even desirable, gross deviations from that ideal can suggest that something has gone wrong with a republican system.

More sophisticated—or at least more committed—Democratic critics sometimes protest that Republicans didn’t really win a popular majority, because many Republican candidates won races in districts that were so Red the Democrats didn’t run a candidate at all. (Also, some Democrats won races in districts so Blue that the Republicans didn’t run a candidate.) If you simply delete all uncontested districts from the final vote totals, the Democrats end up with more total votes remaining.

But this is obviously not a reasonable way to argue that the Democrats had the popular majority. Yes, if you take a bunch of the reddest districts in the entire country and delete them, while deleting a much smaller number of equally-populated deep-blue districts, obviously you’re going to end up exaggerating the Democrats’ national popular support! You’ve thrown out millions of votes for Democrats, but tens of millions of votes for Republicans! This approach artificially suppresses Republican voters in order to support a narrative about “minority rule.”

There is a fairer way to try to account for uncontested districts: simulate the election in those districts as if they had been contested. Using vote totals from neighboring districts, partisan voter indexes, demographic data, and other modeling tools, it’s straightforward to take a pretty educated guess at what the election result in an uncontested race would have been if it had been contested. (We already have pretty good models for simulating election results in districts before an election, and it’s a hundred times easier to simulate after the election, when you know how accurate the polling was.) When some of our best election modelers did this simulation for 2022, it showed that Republicans won the popular vote by a bit less than the official numbers, but they still won it comfortably.

Notably, I (at least) only ever hear the “uncontested districts” argument when it bolsters an argument that Republicans govern by so-called “minority rule.” When Republicans were in the mirror image situation in 2020 (Democrats won by about 3 points, but ran unopposed in 10 more districts than the GOP), I heard no objections that the Democrats hadn’t really “won” a popular majority. (Those objections would have been wrong for the same reasons as the 2022 objections.)

Likewise, when people point to the 2018 Wisconsin election as proof that Wisconsin democracy is dead (Republicans won 63% of seats with 46% of the vote), very few of them point out that this is because Republicans ran unopposed in 8 races, but Democrats were unopposed in 31, hugely running up the D score. The extreme asymmetry in that race is a very good argument for simulating the election results (Just eyeballing it, I think it probably still turns out to be a fairly large R gerrymander; Republicans should indeed have won a majority but not a near-super-majority). In my experience, though, the “uncontested districts” argument is used exclusively to argue that Republicans are a minority even when Republicans are, very clearly, a majority of the electorate.

At this point, the critic must make a broader argument, along the lines that Republicans unjustly refuse the franchise to some Americans (e.g. felons, youths, illegal immigrants) and show that giving the ballot to such a group (and no other) would have resulted in such a large gain for Democrats that it would have wiped out the Republicans’ (sizable) electoral advantage in 2022. The first part of this is a hot-button question about what democratic representation is ultimately even for (and whether and why it might be denied), and the second part of this is harder than you think.

You may be sitting there thinking, “wait a tick! 256 House seats is 58% of the chamber, but you’re saying Republicans would have achieved it by winning only 55% of the vote? How’s that work?”

This is a well-known feature of winner-take-all voting systems. Consider the 1984 presidential election. Ronald Reagan won a large popular majority: 59% to Walter Mondale’s 41%. However, the United States elects presidents by state, and the person who gets the most votes in a state gets all the state’s electoral votes. Because Reagan was so much more popular than Mondale, there was almost nowhere left in the country where Mondale could actually scrape together a majority. Reagan got 59% of the popular vote, but won almost every state (my benighted Minnesota and Washington, D.C. were the only Mondale victories). So Reagan’s 59% vote total translated into 98% of the seats in the electoral college.

The same thing happens in every decisive election using winner-take-all districts, just to a lesser extent. You might not see the effect at all if the winning party wins by 5 points or less, like in 2022, but, if a party wins by around 5 points, you generally start to see them getting a couple more seats than proportionality indicates. If they win by 10 points, they get more. If they win by 20 points, as we saw with Reagan, Katy bar the door. (For some examples in U.S. House elections, see Table 2-2 in this document.)

So, if Republicans had beaten the Democrats 55-45 (excluding the roughly 3% won by third parties, as I’ve done throughout this article), they likely would have ended up with around 58% of the seats.

Gerrymandering can enhance this effect, but only if one party has a large advantage over the other in gerrymanders, which does not seem to me to have been the case in 2022.

The UVA fundamentals model took a lot of previous elections into account, but the last several elections have featured very high levels of partisan polarization, which means there are far fewer voters open to persuasion, with far more rigid geographic segregation. That means there’s much less opportunity for popular vote blowouts and, even if you get the blowout, the seats won’t swing like they used to anyway. The same UVA Center for Politics that produced the 44-seat estimate based on a fundamentals model looked at the map in June and found only 53 Democratic seats could even be considered attainable, while Republicans would be playing defense in 23 districts

This effect is, of course, enhanced by gerrymandering, which tends to eliminate competitive seats and fortify safe seats. As I’ve already noted, there was a lot of gerrymandering on all sides in 2022.

Moreover, even before the midterms, Republicans were already only a few seats away from control of the House. Big seat gains tend to happen when a party is deep in the hole and the other party is electorally overextended—like in 2010, when Republicans were able to win a ton of seats back from Democrats who had won red-state seats during the Obama wave in 2008 and the anti-Iraq wave in 2006. Those seats are easy pickin’s. Picking up 44 seats when you’re already almost at a majority is very hard. No party has controlled 256 seats in the House at the same time since… well, since the Obama wave in 2008, when Democrats walked away with 257 seats. Since polarization has significantly increased since 2008, it’s hard to imagine either party winning 257 seats today—although, of course, political trends only continue until they stop.

Democrats won by 9 in the 2018 anti-Trump backlash, and by 11 in the 2008 Obama wave. Republicans won by 7 in 1994’s sea change and by 5 in 2014—which, honestly, I never quite figured out 2014.

Of course, just like in 2022, all of these popular vote outcomes were somewhat exaggerated by uncontested districts, but I have made no attempt to determine by how much. Assuming these years were like 2022, probably shave a point off each of these margins if you want to “account” for uncontested districts?

…although it should be noted that Angie Craig and Tyler Kistner have faced off in two elections. Both times, there was a third-party “spoiler” on the ballot from the Legal Marijuana Now (“Pot”) Party, and both times the Pot Party candidate mysteriously dropped dead the August before the election. Coincidence? Or murder? Which campaign had more to gain from the Pot Party making a sudden exit from the race? Hmmmm?

This was by far the most interesting discussion point in the MN-2 election.

My anti-fandom of Jensen long predates his idiot run, his disastrous impact on downballot candidates for Secretary of State and State Aauditor, and his post-loss treachery to the pro-life movement. Running Jensen was the stupidest decision the MNGOP has made in my lifetime, and that’s saying something: this same MNGOP re-ran Jeff Johnson (who I loved, but who had already proved he couldn’t win) rather than endorse Tim Pawlenty, literally the only person in the current MNGOP who has ever led a winning statewide ticket.

Trump had the opportunity to make his case against the election results in sympathetic federal courts, and failed, because his evidence was shoddy, scattered, and convincing only to people whose news sources never presented them with meaningful refutations.

That second analysis found that the Trump effect was nearly neutral if you considered all races nationally, but this is because it included every race where Trump endorsed, including 118 uncompetitive blowout races where the GOP won by 15 points or more, wherein the outcome was never in doubt, and where the ideological orientation of endorsed candidates to Trump was fuzzier. (Trump likes picking winners more than he likes ideological consistency. If he were actually good at picking winners, he might be much more of a threat to the Left, both as a candidate and as an executive.) Those districts are not where the red wave fell short. Focusing on the 26 districts where the Trump endorsement plausibly affected the primary and general election fights, the Trump penalty was high.

I’m putting this in italics because it’s really hard to be precise about this, at least with the data I have, which only looks at contested Republican primaries and direct endorsements. If someone has a complete taxonomy of every Republican House candidate and whether each was more rhetorically and ideologically aligned with the Trump wing or the traditional wing, I’d love to get my hands on it.

After all, we know these numbers are wrong. As you can see, the final generic ballot average in 2022 estimated the GOP would win the national popular vote by 1.5%. As you know, they ended up winning by 3%. That’s a pretty small polling error, as these things go, but the error means we should assume this entire chart (probably) underestimates GOP support by a point or two throughout the election cycle. That’s okay, because we aren’t looking at the numbers on any specific date, we’re looking at how they changed.

Put another way: even if the generic ballot systematically underestimated GOP support, it presumably did so consistently. An actual change in support from a +3 GOP to +1 GOP might show up on this chart as a change from +2 GOP to TIE, but, either way, it’s a two-point shift. Still with me? Okay, back to the chart.

At least partly. There should be some overlap. For example, if Lauren Boebert is running as the Republican in your district, that might lead you to vote against her and sour you on the Republican brand in general.

One of these losses, Michigan, can plausibly be tied to abortion (there was a ballot measure to legalize it there), but tying the other losses to abortion would be a reach.

Pennsylvania had Doug Mastriano, who vocally supported protection-from-conception and was very unattractive to voters, but he had no serious chance of getting his state legislature to ban abortion, even if he’d won. Minnesota’s Jensen ran away from abortion as fast as he could, and had very little room to do anything about it anyway, since the state Supreme Court created a “constitutional” right to abortion in Minnesota several decades ago, and state courts have recently expanded it. Abortion was not, to my knowledge, a significant issue in the Alaska race. Alaska had few legal protections for the unborn, none passed recently, and no ballot referendum, so it was not meaningfully “on the ballot” there.

In my experience, when most people say they are concerned about “the future of democracy in America,” they mean they’re worried about election denial, January 6th, and so forth.

However, a sizable chunk of Trump-supporting Americans also tell pollsters they are concerned about “the future of democracy in America,” but they mean something very different by that. These voters are worried about the massive voter fraud they believe illegitimately elect Joe Biden president, and their main objection to January 6th is that it didn’t succeed in pressuring Mike Pence and Congress to violate the Twelfth Amendment.

These are not the voters who were turned off of the GOP by the J6 hearings, therefore not the voters we are interested in here, so I tried to exclude them from this sample by removing all Trump 2020 voters from the sample. That’s what I mean when I say that this is a sample of Democratic voters.

That’s the main difference between my chart and the Kaiser Family Foundation’s similar chart, which included all voters… and found similar results, so I guess no biggie.

Note: this is unweighted. Based on the Kaiser Family Foundation’s similar results for all voters, I don’t think it makes a difference, but it’s important to note that kind of thing!

I define “abortion moderate” as someone who positively supports an unlimited right to legal abortion during either the first trimester or until fetal viability, but not beyond. They’re “pro-choice,” but only to a point, and certainly not “pro-life.” I think these people are the least rational in the abortion debate, but they are also closest to the American public, which nobody would call rational about abortion.

I’m defining “competitive district” here as a district with a Cook 2022 PVI between D+10 and R+10. There were 169 competitive districts in the 2022 midterms, and 112 competitive districts where the Republican candidate was not the incumbent, so my sample of 24 of them is not great, not terrible.

In AZ-6, CA-3, FL-4, FL-15, IA-3, MI-3, MI-8, NV-1, NV-3, NY-1, NC-11, PA-7, PA-8, PA-17, VA-2, and WA-8. Correct me if I’m wrong about classifying any of these candidates as pro-life.

If you really want to do an apples-to-apples comparison, you might want to restrict this to just the 3 pro-choicers who defeated America First candidates in primaries. That makes the result -0.2 points instead of -0.3 points, but the sample size is dangerously small, and obviously makes no meaningful difference.

UPDATE 21 August 2023: Thanks to a comment, I discovered an error in the way I assessed Lisa Murkowski’s performance in Alaska. Because of the complexities of Alaska’s instant runoff voting system (detailed in the comments), and the particular way this IRV election played out, there’s seems to be no obvious fair way for me to compare Murkowski’s performance to that of any other Republican outside the state of Alaska. I should have excluded her from this analysis entirely. For details of how I initially concluded that she underperformed, and why I no longer think the numbers show that (or anything conclusive about Murkowski’s performance), see this comment, linked previously.

I could find no abortion position for New York Republican Joe Pinion, so I excluded him from both camps. FWIW, he missed his index by 3.2%.

In two of them, California and Vermont, abortion was under no actual threat, and the ballot measures were transparently an attempt to drive up turnout, akin to the definition-of-marriage ballot referenda red states used to drive Evangelical turnout in 2004.

In four states, however—Michigan, Kentucky, Montana, and Kansas—it was very plausible that abortion could be restricted or banned if the ballot measures failed. In Michigan, abortion was already banned under the state’s pre-Roe anti-abortion law.

Kansas’s abortion ballot referendum was a couple months before the midterms, but, like Nate Cohn, I suspect Democrats’ strong performance in Kansas’s only competitive district (the 3rd) had something to do with lingering effects from the referendum, so I included it here.

I got this from the Guttmacher Institute’s state legislation tracker for 2022. Six of these nine states passed protection-from-conception laws, so these aren’t penny-ante restrictions, either.

Kansas-3 was insane: the Democrat took an R+1 district and won by 12 points, destroying a pretty traditional, non-Trumpy Republican woman with previous campaign experience. This was all the more surprising because Republicans overperformed in all the state’s other, uncompetitive districts.

On the other hand, the same Republican candidate lost the same district by 10 points in 2020, so maybe she has serious campaigning weaknesses that I don’t recognize from here in my armchair. We can’t blame Dobbs for her defeat in 2020, after all.

These are district-specific effects, and there aren’t that many districts involved, so, individually, these don’t go a long way toward explaining the Republican deficit in the national popular vote. Like, yeah, in the 25 districts with a referendum excepting California and Vermont, Republicans underperformed by 2.7 points, but we’re only looking at 25 districts, so, even if we believe this underperformance was caused entirely by the referenda, it still only explains about one-fifteenth of the Republican deficit in the national popular vote. Nevertheless, it’s important to look at this to see how (and to what extent) abortion supporters can use abortion measures to drive support for Democrats in the districts where abortion measures are happening. Even if it didn’t have a big impact on 2022 nationally, it could in 2024.

That’s not how it would actually work in practice, obviously.

A few areas where I think there’s especially wide space for disagreement:

I assume in this article that Republicans “should have” won the national popular vote by 6 or 7 points, like they did in 1994, 2010, and 2014. However, if you think fundamentals were so dire that Republicans “should have” won the national popular vote by 9 or 10 points, then there’s several more “missing” points to explain, and thus more “room” for abortion to account for some of them (although blaming abortion for the gap would still need to be at least suggested by other data). Republicans haven’t won by 9+ since 1946, but Democrats won the House popular vote by 9+ in 2018, 2008, 1990, and 9 other elections since 1946, so it’s not something Republicans do, but it’s not insane to suggest that they could.

A more comprehensive survey of Trumpy/MAGA/America First candidates might find the Trump Effect less pronounced than Nate Cohn and Phillip Wallach did, respectively, since they mostly focused on competitive districts. I’m not very worried about this, since competitive districts were mostly where Republicans fell short anyway. (In both red and blue safe seats, there was much more evidence of a wave—but running up the score in safe seats, for either side, doesn’t translate to seats.)

Obviously, as I myself concede, the state level data points a few different ways, and a few more data points leaning one way or the other could make my whole hemming and hawing routine look ridiculous. I’m especially curious to know what that data looks like after, for example, the Ohio abortion referendum this fall.

In Michigan and Kansas, voters were pretty much forced to decide between “elective abortion totally illegal” and “elective abortion legal up to the last day of the ninth month,” with no middle ground. In Ohio, voters are choosing between “elective abortion legal up to the last day of the ninth month,” and the much-more-moderate-but-still-not-exactly-moderate position of “elective abortion illegal after fetal heartbeat, even in cases of rape.” Does that have the same pull for voters? Even in a pretty pro-life, pretty red state like Ohio?

From a data standpoint, it will be interesting to find out. (Alas, no House races are contested this year, so we won’t see Ohio’s ballot measure have any direct impact on House races.)

UPDATE 29 August 2023: When I originally posted this article, I apparently forgot George H.W. Bush. That kinda sums up the first Bush Presidency, but still, I regret the error.

There is powerful evidence that, while Republican primary voters often claim not to care about “mean tweets,” many of them actually love mean tweets, so much so that they will vote for mean tweets over the possibility of winning majority support or actually getting anything done in office.

“I also find it interesting (but, again, sample size insufficient) to note that the three Republicans who ran for U.S. Senate as pro-choicers (Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Tiffany Smiley of Washington, and Joe O’Dea of Colorado) performed substantially worse than their peers, even their Trump-aligned peers."

Can you clarify why you feel Lisa Murkowski performed substantially worse than her peers? You went into no detail about it, only discussing Joe O'Dea. Alaska's ranked choice voting system makes it harder to compare its election results to those of other states--but Murkowski in the general election did defeat the Trump-aligned, pro-life Kelly Tshibaka.

"At this point I think it entirely likely that the Democrats hold the Presidency, and take back the house by a healthy margin in 24. I think there is a good possibility they hold the Senate even though that path is hard for them, and Dobbs gets all of the credit. -John13"

I meant to respond at the time of your writing, but every time I typed something out, it was just speculative. In the end, I made a calendar reminder to come revisit things today. We have some differing views on the extent gerrymanders played in some House races, but I feel very little motivation to revise what is quoted above. The Dobbs effect seems undeniable at this point, and whil holding the Senate is still perilous, the signs are there that it could happen tonight. We both know this is not a coin flip, it is a polling error away from a landslide, and as of right now Harris appears to be pulling away in Iowa which primes a blue wave.

At least according to me.

We will know tomorrow.

I just read your essay about the various referendums, and those have been on my mind as well. I think the only possible loss is Florida, but I am not giving up hope there either. Even if it does fail, it could take down Scott, which is a pretty decent silver lining from my perspective.

A few moments ago, I read that Trump won't say which way he actually voted on the referendum and whined that the reporters should stop asking him about it. That seems like a pretty good snapshot of where the GOP is on abortion going forward. This could be blustery on my part. I figured I should say it now, to put a little skin in the game. It sure feels like the polls needed to weight Dobbs, and women a lot higher.

You might want to preload the Tums. I am considering doing the same.