Election Night Preview: 2022 Edition

How to impress your friends by understanding the data and its implications before anyone on network news.

The day of the Brexit vote, the very first constituency to report results, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, reported a defeat for Brexit, 51% Leave to 49% Remain. The defeat for Brexit there was expected. However, the margin was wrong: experts had expected Brexit to fail in Newcastle by 12 points, not 2 points. Newcastle had been a “safe state” for Brexit opponents that turned into a very narrow win. I was over at my parents’ for dinner, just buzzing by the computer for a quick results check, didn’t even bother sitting down—and I remember seeing that result, sitting down heavily, and thinking, “Welp. The U.K. just left the E.U.”

The rest of the night went the same. Areas that were expected to vote for Brexit by a narrow margin voted for it by a large margin; areas that were expected to oppose it by narrow margins ended up supporting it by narrow margins. There were a few places where the anti-Brexit “Bremain” vote did better than expected, as there always are… but not many. Networks finally called the race for Brexit hours after the result was clear.

This happened again in the 2016 presidential election. I told my family at around 8:15 PM (Central Time) that Trump was probably going to be the President-Elect, because I could see that all the states Trump needed were getting called for him (or were on the cusp of it), while all the states Clinton needed were tossups… and leaning red.

Once again, in 2020, I was closely tracking a random House race in suburban Kentucky and realized from looking at that one race that, holy cow, the polls actually had missed that year, and missed big. I buckled in for a long, long night and finally went to bed after I saw the Milwaukee results put Biden over the top1 in Wisconsin.

I will now tell you all my secrets.

The Stakes

The U.S. 2022 midterm elections will determine control of the U.S. House, the U.S. Senate, several state legislatures, a number of governorships and associated offices (like SecState), and whether abortion is legal up until the moment of birth without parental notification or consent in Michigan (among other ballot measures around the country).

This article is mostly concerned with national races. I’ve discussed the national stakes before, but, in a nutshell:

If the Republicans get the House, they can join budget negotiations, block all purely partisan legislation (they can’t right now because of the budget reconciliation process), and investigate the White House.

If Republicans get the Senate, they can do all that, plus force the White House to negotiate over nominations (especially judicial nominations).

If Democrats hold the House and win two more Senate seats (fairly likely if they manage to hold the House), they can abolish the filibuster and pass transformative legislation affecting every nook and cranny of American law and life.

The state races are important, too. I have strong opinions about the Minnesota Attorney General race2, the Dakota County attorney race,3 and the gubernatorial race4... but every state is different, and I'm no Daniel Nichanian. So this article is mainly about the House and Senate races.

Ground Rules: Definition of a Wave

There is so, so much loose talk about “wave” elections. Politicos on all sides have heavy incentives to exaggerate their victories, converting narrow wins to “mandates” and “tsunamis.” Very modest results are sometimes referred to as “tsunamis.” The hype train on the Right has already left the station. So let’s set some ground rules about what counts as a “wave.”

The “canonical” wave elections are 1946, 1948, 1958, 1964, 1966, 1974, 1980, 1982, 1994, 2006, 2008, 2010, and 2018. Everyone agreed these were “wave” elections, not just partisans. In those elections, the “wave” party gained an average of 44.8 seats in the House of Representatives; a median of 47 seats; and a minimum of 21 seats. That minimum came in 2008, and was the result of a peculiar double-wave, which can’t happen this year.5 Excluding 2008, the smallest wave election was in 1982, when the “wave” party gained 26 House seats.

By contrast, in non-wave elections since World War II, the winning party gains a few House seats (averaging in the high single digits). In the biggest non-wave elections, one party gained 22 House seats6.

From this, we can derive some pretty decent definitions:

A “wave” election is an election where one party gains 25+ seats in the House.

A “tsunami” election is a better-than-average wave, where one party gains 45+ seats in the House.

For the 2022 midterms:

In a Republican wave, the GOP would win 238+ House seats.

In a Republican tsunami, the GOP would win 258+ House seats.

In a Democratic wave, the DEMs would win 247+ House seats.

In a Democratic tsunami, the DEMs would win 267+ House seats.

Accept no substitutes!

A wave generally means large gains in the House and, in a presidential year, almost guarantees victory in the White House.

However, a wave does not necessarily translate into large gains in the Senate. The Senate only elects one-third of its members each cycle, and some cycles are inherently more difficult for one party or another, just because of which states are up for election. 2022 is not a very good Senate map for Republicans. 2024 is a horrible Senate map for Democrats. This is luck of the draw.

Moreover, U.S. Senate elections are much more candidate-driven than U.S. House races, so individual qualities like being a quack or a horrible human being can have a much larger impact, potentially leading candidates to ruin despite the rising tide of a wave. Both parties did pretty poorly on candidate selection in 2022, but Republicans, in particular, screwed the pooch.7

Sean Trende went deep on how wave elections affect Senate results in a 2014 article, if you want to explore that further. Let’s move on.

Ignore the Vibes

The Vibes right now are screaming “Big GOP Wave Big GOP Wave Big GOP Wave.” You see it everywhere in the media right now, right, left, and center. The other day, the New York Times put out four extraordinarily good polls for Democrats, showing them holding strong in four key districts (in one case by a jaw-dropping margin), and then headlined their article, “Polls in Four Swing Districts Show G.O.P.’s Strength in Midterms.” No! Let me assure you, those polls induced small cardiac events in G.O.P. data apparatchiks!

But The Vibes for this election are so strongly pro-GOP right now that The Vibes alone overrode the actual data the Times had so painstakingly collected. I don’t mean to single out the Times, either (much as I enjoy singling out the Times for criticism); this is happening all over. It feels a lot like that time in 2012 when The Vibes were screaming that the Obama/Romney election was a lot closer than the polls said. In fact, the polls had substantially underestimated Obama, ultimately making 2012 an objectively bigger polling miss than 2016.

A big GOP wave is certainly possible, but conventional wisdom—aka The Vibe—has gotten way ahead of the data on this. If you want to put a number on how far ahead, compare PredictIt’s current betting market for the Senate outcome (which gives the GOP a 72% chance of winning the Senate) to the three data-driven models (all of which give the GOP about a 55% chance of winning the Senate).

As I have written before, it’s not just that conventional wisdom is often wrong, but that it’s almost reliably wrong. Your best bet is to ignore The Vibes entirely. (Your second-best bet is to bet against The Vibes.)

The Data: Expecting a GOP Win, Maybe a Wave

Most real election experts (the Cook Political Report, the UVa Center for Politics, Inside Elections, Sean Trende, etc.) think that the “modal outcome” in tomorrow’s elections is going to be a GOP win in the House and a close race for the Senate (with perhaps a tiny GOP edge). They anticipate the GOP gaining 20-30 House seats.8 The high end of that would qualify as a small GOP wave, albeit barely.

Data-driven election models are a little more bearish than those experts. De Civitate’s favorite forecast model, FiveThirtyEight, forecasts the GOP landing on exactly 228 House seats (a 15-seat gain), which would be a tidy victory by ordinary midterm standards, delivering control of the House to the GOP… but definitely not a wave. DecisionDeskHQ forecasts 231 GOP seats (a 17-seat gain). The Economist forecasts 225 GOP seats (a 12-seat gain).9 JHK Forecasts has the GOP on 231 seats (a 17-seat gain). In other words: the modal outcome is a good solid GOP win, but no wave.

But that’s only the “modal outcome.”

The “modal outcome” is the least unlikely outcome. That doesn’t make the modal outcome likely; it’s just less unlikely than everything else. For example, suppose your kid’s school has a raffle. You buy 100 raffle tickets—more than any other single individual. In total, the school sell 5,000 raffle tickets. Your personal odds of winning the raffle are pretty bad: 100/5000 = 5% chance to win (or a 95% chance to lose). However, you have the most tickets, so you are still more likely to win than everybody else. You are unlikely to win, but less unlikely than everybody else. Your winning the raffle is the modal outcome.

This is very important for understanding election expectations.

While a GOP non-wave victory is the modal outcome, it is not actually likely to happen. It is just less unlikely than everything else. Let’s break that down.

How It Might Go Down: Red

Polls are powerful tools that tell us a lot about how the American people are thinking about all kinds of things. But they are tools, not oracles, and understanding how easily they can go wrong is key to understanding how to use them correctly. In most elections, the polls collectively miss the final result, to some extent. Historically, the direction and magnitude of the miss is not predictable in advance. That means that a lot of things can happen… especially in a high-turnout, close election like this one.

On a “normal” night, it’s a “good” night for Republicans. The polls are pretty much spot-on overall, as they were in 2018. They land between 224 and 231 House seats (+11 to +18). This is not a wave, but it’s plenty enough for control. The Senate is a photo finish, with results likely not known until some time on Wednesday, or perhaps even later, but it’s probably a 50/50 or 51/49 Senate. This is the modal outcome… and it is about 25% likely.

On a “great” night for Republicans, the polls miss, but only by a point or two… and/or the GOP has some good luck in how a few close races break. The GOP gains 19-26 House seats (232-239 total seats). The GOP wins the tossup Senate races in Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Nevada (for a 52-seat Senate), but Arizona and New Hampshire remain well out of reach. At the upper end of this spectrum, the GOP could technically achieve a small but real wave. The election experts (who predicted this outcome) end up looking a little smarter than the data-driven models (which were more bearish). This is about 20% likely.

In a “true wave” for Republicans, the polling miss resembles the miss in the 2016 elections (3-4 points). Republicans pick up 27-38 House seats (240 to 251 total seats). In the Senate, the Arizona/New Hampshire firewall trembles, and even Democratic incumbents in Colorado and Washington start to sweat a bit. A 54-seat Senate trundles into the realm of possibility, although 53 still seems more believable. This is about 15% likely.

In a “tsunami” for Republicans, the polling miss looks like the 2020 polling miss (5-6 points), maybe worse. Republicans pick up 40-50 House seats (253-263 total seats) and 54 Senate seats for sure, but this is the realm where winning the Washington or Colorado Senate and going all the way to 55 or 56 seats becomes really thinkable. Any gains beyond this are implausible. This is about 4% likely.

How It Might Go Down: Blue

Error doesn’t have to favor the Reds, though. Maybe in the past decade you’ve gotten used to the polling errors always going their direction? Yet there’s plenty of reasons to believe that Democrats could benefit from a polling error this year.

On a “mediocre” night for Republicans, the polls miss by only one or two points, and/or the Democrats get lucky in a few close races. The Republicans gain 5-10 seats in the House. They do win the House, but only barely. Democrats win the Senate, whether by maintaining their current 50/50 even split or getting a 51/49 advantage. Even a 52-seat Democratic Senate majority is possible, given the number of close Senate races. Incoming Speaker Kevin McCarthy must maintain rigid discipline to keep his fractious caucus intact and capable of governing. This is about 15-20% likely.

On a “bad” night for Republicans, the polling miss resembles the miss in the 2012 elections (3 points), and that… hurts. (If you’re a Republican.) The GOP fails to flip the House. At best, they gain 4 seats. At worst, they lose 4 seats. The Senate is gone, and the only question is whether the GOP can cling to their seats in Wisconsin, Ohio, and North Carolina in order to prevent a 52-seat Democratic majority and save the filibuster.10 They might pull it off... but it will be an awfully dicey business. This is about 10-15% likely.

On a “catastrophic” night for Republicans, the polling miss is huge, like nothing conservatives have seen since the debacle of 1998 (but worse; the miss that year was only 4 points). The Democrats gain 5+ seats in the House, and end up with the most powerful progressive governing majority since FDR—not as large as the Obama Congress of 2009, but large enough, and far far far more ideologically disciplined. This is about 4% likely.

Yes, you are reading that correctly: the Republican “wave” you’ve been hearing so much about? It’s only slightly more likely, according to our best and most successful predictive models, than a GOP wipeout that leaves the Democrats in striking distance of revolutionary change. Ignore The Vibes.

How to Track It: Race Calls

Let’s finally circle back to that Brexit story from the beginning. Now that we understand the range of possible outcomes, how can we know early on which outcome is actually happening?

One obvious way is to track race calls. If toss-up races are getting called for Republicans, and leans-blue races are too close to call, that suggests a strong night for Republicans. If toss-up races are going to Democrats and leans-blue races are too close to call, that suggests… you get it.

A good early indicator is whether the New Hampshire or North Carolina Senate races are competitive. NH is a lean Democratic race; NC is a lean Republican race.

Senate races in Vermont, New York, Maryland, South Carolina, Kentucky, Alabama, and Indiana should all be called the instant polls close. Then we wait. If NH gets called fairly quickly while NC languishes, that’s probably a bad sign for Republicans.11 On the other hand, if North Carolina is called early, but we're waiting on New Hampshire, that's bad news for Democrats. If they're both called at around the same time (ish), and the Democrat wins NH while the Republican wins NC, then that’s pretty much in line with expectations and we may be on track for a night with low polling error.

The great Dave Wasserman suggested some good House benchmarks:

The inverse of this, as I see it:

If NC-13’s Hines (R) or MI-10’s James (R) lose, Republicans are significantly underperforming, and we’re in “mediocre” to “bad” territory.

IF FL-27’s Salazar (R) or IA-1’s Miller-Meeks (R) lose, Republicans are on the brink of catastrophe.

However, I don’t love waiting for “calls.” Since calls come in without final vote totals, you need a bunch of race calls to get a good picture of what exactly is going on, of exactly how good the night is going to be for one side or the other.

How to Track It: Quick-Counting Districts

Instead, I like to use clear numeric benchmarks.

First, I find a district where all the votes have been counted. Doesn’t matter if the district was competitive or not; I just want to know if all the votes are in.

Then, I subtract the winner’s popular vote percentage from the final FiveThirtyEight projection for that candidate.

NERDY BIT: You can also calculate this from the winner’s margin over the loser (instead of popular vote percentage). Sometimes, you have to do this, because third-party candidates did weird stuff to the final results. However, if you use the margin instead of the winner’s vote share, you have to divide your answer by two.

The answer is the polling error in that district.

I’ll run you through an example.

Last election, I used KY-6 (represented by Republican Andy Barr) as my benchmark. Once all the votes were counted, I saw that Barr actually won 57.3% of the popular vote. FiveThirtyEight had projected Barr to win 52.9% of the vote. That’s a polling error of D+4.4%.

Or, using the margin: I saw that Barr actually won by 16.3%. FiveThirtyEight had projected Barr to win by 8%. 16.3 - 8 = 8.3%. We have to divide this by 2, which gives us a polling error of D+4.15%.

In my 2020 election preview, I had said this result would mean something between a “good” and “great” result for the GOP, one that could make the Senate competitive and, at the upper end, turn the presidential race into a photo finish. This turned out to be, well, correct!

In 2020, I found it pretty irritating that I had only set benchmarks for KY-6, because KY-6 did not count as quickly as I expected. Other districts were faster. This year, I’m going to try to be more flexible with my benchmarks. I intend to keep a close eye on the races in KY-6, VA-10, RI-1, RI-2, NH-2, VT-AL, and NC-9, but I’ll take anything that counts early! These districts are kind of all over the place demographically, so any one of them might throw up a misleading indicator, but, after we have full counts from even two or three districts, we should have a pretty clear idea which way the night is going. Here are some general benchmarks if you want to do this yourself:

D+5 polling error (or more): GOP tsunami. (Odds about 1-in-25.)

D+3 or D+4 polling error: GOP wave. Big majorities in both houses. (Odds about 1-in-6.)

D+1 or D+2 polling error: “great” night for Republicans. +19 to +26 House seats and narrow Senate control. (Odds about 1-in-5.)

<1% polling error: “good” night for Republicans. +11 to +18 House seats; Senate a toss-up. (Odds about 1-in-4.)

R+1 or R+2 polling error: “mediocre” night for Republicans; control of the House but just barely; narrow loss of the Senate. (Odds about 1-in-5.)

R+3 or R+4 polling error: “bad” night for Republicans; loss of both House and Senate. (Odds about 1-in-6.)

R+5 polling error (or more): “catastrophic” night for GOP. (Odds about 1-in-25.)

How NOT To Track It: Incomplete E-Day Results

In this election, as in 2020, some states are going to be counting the early vote quickly, followed by the election day vote. Other states will count the election day vote quickly, followed by the early vote. Some states will have early votes trickling in for days after the election. Nevada, in particular, might be too close to call for a week if the Laxalt/Cortez-Masto race is as close as it looks.

Because Republican voters tend to favor election-day voting, while Democrats tend to prefer early voting, you must be very careful not to draw inferences from vote counts that are disproportionately missing one or the other. Endless waves of embarrassing silliness (also crimes) could have been avoided in the aftermath of the 2020 election if all Republicans had realized (for example) that Pennsylvania knew in advance that it would take days to count its early vote (they announced this!), and that any firewall the GOP built up on election day would therefore be gradually worn down by 2020’s mammoth Democratic early vote.

You can draw inferences about a district if the race is called or if the vote is completely counted. If you’re feeling more daring and want to draw inferences from districts that haven’t been fully counted yet, at least double check that you have the full picture and that your inference isn’t about to be swamped by hundreds of thousands of red- or blue-leaning votes you didn’t account for.

What the Early Vote is Hinting At

You should never, ever, ever try to interpret the early vote. It is a fool’s errand. Because you do not know the makeup of the electorate on election day, you simply cannot discern whether a strong early vote performance for a party means the party is turning out in record numbers… or if a lot of the party just decided to take advantage of early voting this year. Early vote analysis has been notoriously treacherous. It sounds so intuitive, and its pitfalls seem like things you should be able to account for. But you can’t. Early vote analysis gave a whole lot of false hope to both Clinton and Biden supporters, and they paid for it later (although Biden still eked out a narrow win). Early vote analysis is always hopium. Don’t take a hit of it. Don’t fool yourself.

…unless your name is Jon Ralston of the Nevada Independent.

Ralston alone, among all prognosticators, has been able to take advantage of Nevada’s unusually transparent voting system and his own deep knowledge of the state and its voting history to produce the holy grail: election forecasts based entirely on early vote analysis that are measurably more predictive than the best election forecasting models we have. As far back as 2010, Ralston was the only guy on the market saying that Harry Reid was going to beat Sharron Angle… which Reid did, handily. I believe FiveThirtyEight had Angle at around 80% to win just before she lost by 6 points. (It helps that Nevada is really hard to poll, which gives Ralston a bit of an opening.)

So, if you are Jon Ralston, you are allowed to opine about what the early vote indicates. Nobody else. And only in Nevada.

Right now, Ralston is seeing… a really close race!

In the Senate, Ralston thinks we are headed for a narrow victory by the Democrat, Cortez-Masto, with a margin of about 2.0 points. The FiveThirtyEight model Cortez-Masto losing by a margin of 0.2 points. If Ralston is correct, the polling error in the Nevada Senate race will turn out to be (2.0-0.2) / 2 = R+0.9. That’s consistent with a “good” night for Republicans, although tilting toward “mediocre” territory.

I’ll skip the details of each race, but, in the House, Ralston predicts:

NV-4: D+0.9 error (“good” night for Republicans, tilting toward “great”).

NV-1: R+1.2 error (“mediocre” night)

NV-3: R+0.2 error (“good” night)

NV-GOV: R+0.35 error (“good” night)

Obviously Nevada is only one state, and a state with pretty peculiar demographics, at that. Even if you’d trust your life to these predictions (and, to be clear, even Ralston is saying that anything could happen), you couldn’t generalize Nevada to the entire country.

Still, this little scrap of usable data from an actual election in progress suggests one useful possibility: that the polls for this year are pretty darned close to exactly correct, at least in Nevada. I’m calibrating my expectations accordingly. The polls might just have the whole election cinched up this year, as they did in 2018.

Or they might not. Ralston agrees with every other analyst I’ve read: this is an unusually uncertain election, where enough races are close enough that an unusually large number of things could realistically happen. Ralston says he has never been this uncertain on the eve of an election. In the final pre-election FiveThirtyEight podcast, Nate Silver said the same thing.

What the Polls are Hinting At

In the final week or so before an election, we enter a polling “fog of war.” At this point in the cycle, many polling firms are more concerned about protecting their reputations than they are about getting and publishing useful results that add to our information about the race. This leads to something called “pollster herding.”

Pollsters do not suddenly start rigging their results… but they do stop publishing “weird” results that fall outside the current polling consensus. Weird polls are quietly “spiked” in the lab, unpublished. If the polling consensus is correct (and it often is, or nearly so) that’s not a big deal. But if the polling consensus is wrong, it can lead herders to spike accurate polls while publishing inaccurate ones. It makes sense that pollsters want to cover their rear ends, but this is a significant cause of overall polling error.

So, in the final days of a cycle, it’s worth paying attention to polls that fall outside the consensus, especially from high-quality traditional pollsters. The ur-example here is the 2014 Senate race in Iowa. The polling average had Joni Ernst up by only 2 points against her challenger, Bruce Braley, with all polls being between +1 Braley and +3 Ernst. Then the Selzer Group of Iowa, an A+ pollster, released a poll showing Ernst up 6 points. Many people excoriated it, or at least dismissed it as an outlier. Then Ernst won by 8.5.

This cycle, most of the final polls have not come from the highest quality pollsters, and those that have mostly fit within the current polling consensus. Selzer & Co., for their part, gave Chuck Grassley’s Senate campaign a heart attack last month by reporting that he was only winning by 3 points (a race he really ought to be winning by 10-15 points), but their final poll of the race last week had Grassley up by 12, right in line with other polls. You never want to read too much into a single poll (not even a Selzer poll), but this pattern repeats elsewhere. Are the highest quality pollsters herding because everyone has lost confidence in polls this cycle? Or are the highest quality pollsters publishing accurate results and it’s indistinguishable from herding because the polling consensus happens to be right this cycle? I lean toward the latter, especially because it agrees with our early vote evidence in Nevada: the most likely explanation is that polls are converging on reality, which suggests that we are heading toward a “good” night for Republicans.

However, I thought this was interesting: the final ABC News/Washington Post poll of the cycle showed a significantly narrower enthusiasm gap between the two parties, which suggests that demoralized Democrats have roused themselves to cast ballots in the past few days. Republicans still lead in enthusiasm and on the generic ballot, so this doesn’t indicate the Democrats are going to hold the House or anything, but it suggests some tightening that isn’t reflected in the overall consensus, which may lead to more of a “mediocre” night.

I also haven’t forgotten October 27th’s New York Times/Siena College polls, which showed great results for Democrats (on my scale, their results indicated a “bad-to-catastrophic” night for Republicans). That’s a great pollster, and it took courage to publish such outliers. I also note that the only stubborn outlier in the generic ballot poll right now, Morning Consult/Politico, shows Democrats leading on the generic ballot by +5—again, a “bad-to-catastrophic” night for Republicans if true. (Morning Consult/Politico is not generally considered a top-quality pollster, though, so, grain of salt.)

On the other hand, party internal polls are not so subject to herding. You can't spike a commissioned poll just because the result is embarrassing. While we don’t actually have the internal polls from the two parties,12 we do know what those polls are saying: they're saying that the Democrats are in a ton of trouble. We know this because both parties have, in recent days, allocated resources to races that have no business being competitive on anything less than a "great" night for Republicans. I'm talking races like the New Hampshire and Washington Senate races and the Oregon gubernatorial election. Parties are pretty fanatical about not wasting money. If they're spending there, it's because they're seeing close races there. This suggests a great-to-tsunami night for Republicans.

Trying to glean a lot of information from early indicators like early voting and herding detection is a very iffy business, closer to Professor Trelawny's occupation than real forecasting. I stand by the odds I gave earlier, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see these faint signals cancelled out completely (in either direction). But this very limited early evidence suggests that the polls this year might just be alright after all. While there are signs pointing in all directions, the clearest and strongest signs (in my opinion) point toward a “good” night for Republicans. It might end up a "great" night, and I secretly suspect it will turn out a "mediocre" night, but the polls wouldn't be off by a lot either way. That means no "Roevember" securing the House for Democrats, and no Red Wave carrying Lee Zeldin (R) or Scott Jensen (R) into the governor’s offices in New York and Minnesota.13

Of course, even if that’s true (and there’s a very healthy chance it isn’t!), Election Night always has a few upsets in store. So buckle up!

My Feed

On election night, I intend to be keeping in touch largely through ABC’s live coverage, because Nate Silver is working their decision desk. When ABC is on commercial break, I’ll be watching CNN, where the excellent Harry Enten will be doing the same work.

Because Nate Silver is only one man, and because news networks overall are slow and stupid, I will also be closely monitoring an Election Data Twitter list, full of the smartest minds in psephology, which I’ve found very useful. Dave Wasserman (@Redistrict), famous for his “I’ve seen enough” tweets (which are among the fastest reliable election calls on the planet), might get a tab all to himself.

UPDATE 3:00 PM: I copied the Election Day Twitter list to my own Twitter account, added some more useful accounts, and updated the link.

DecisionDeskHQ tends to get vote totals logged fastest and makes terrific early calls (or, at least, it has in the past). FiveThirtyEight will have a liveblog, but, since Nate Silver won’t be there, I’m not certain I’ll care. I might tune in for Nathaniel Rakich.

UPDATE 3 PM: Nate says he will be there.

If I’m feeling up to it, I may even place a few bets on the betting markets as the results roll in.

UPDATE 3 PM: I will also be following the Bolts Results Cheat Sheet, because nobody tracks consequential-but-invisible state-level supreme court elections and ballot initiatives better than Bolts Magazine.

I will deeply mourn the fact that, to the best of my knowledge, the New York Times Needle will not be up and running this year. If I had a Times subscription, I doubt there’s going to be a better liveblog of the election than Nate Cohn's Upshot.

MAJOR UPDATE 1:08 PM: Big surprise! The Needle is BACK, BABY! The Needle does a lot of benchmarking automatically in the background, which means those of you who don’t want to be doing math can mostly just watch the Needle! However, a warning: the Needle broke down in 2018 and we all had to go back to doing math.

With all these tools, you should be able to run circles around network news anchors and call the race for yourself hours early. (Obviously, I’m still staying up to watch all the results roll in.)

Happy election night. At least we won’t have to watch God of Egypt this time.

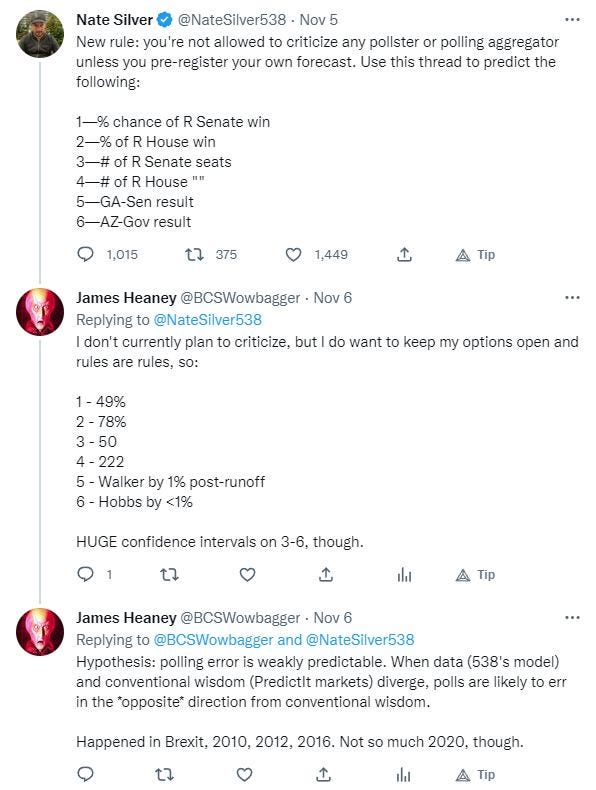

UPDATE 23 NOVEMBER: Bragging because I nailed it. Check the dates:

The Walker race is the one prediction we don’t have yet, and I may still miss on that.

To be clear, a good chunk of this is luck. It’s impossible for even the best prognosticator to reliably predict the results of ~460 simultaneous elections, many of them close. All you can do is load the best model you can into your head and shoot your shot. The laws of probability dictate that even the best shots with available data will usually miss.

But my shot hit dead-on, which is good evidence that I’m lucky and very good at this.

People later were all, “ooo late-night vote dumps!” but that just told me that a lot of people had never before stayed up until 4 AM watching election results. For 4 AM veterans like me, there was nothing weird about the Wisconsin results or counting process.

The Republican, Jim Schultz, is a good man who will usher in much-needed change—and, unlike Ellison, Schultz will defend Minnesota’s bipartisan compromises on abortion, such as informed consent and mandatory waiting periods, rather than connive ways to get those laws nullified through the back door.

Non-partisan race, but Kathy Keena gave the West St. Paul Reader the only answers a qualified candidate could: “As the Dakota County Attorney, I must support the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the State of Minnesota. In that role, one of my primary responsibilities is to oversee the appropriate enforcement of constitutionally sound laws enacted by our state legislature… this is a non-partisan position and I believe questions [about various social issues and policy measures] are more appropriately answered by legislative candidates."

Meanwhile, Matt Little disgraced himself by vowing to nullify constitutional laws he happens to dislike. Matt Little’s vow is just as much an attack on democracy as the worst election-denier ravings from Marjorie Taylor Greene, and I hope voters give him the next several years to think about it.

Scott Jensen is a turd, the only person on the Minnesota ballot this fall whom De Civitate has specifically and publicly called out as a liar. (He’s been terrible on a lot of things, but that’s the only one I wrote up.) He’s going to lose, and he deserves to. I am voting for him anyway, because we are all trapped in a two-party system of our own design.

By “double-wave,” I mean that Democrats had just had a wave in 2006, and so they already controlled all the low-hanging fruit in the House. President Obama’s near-landslide election could only carry so many more House seats into the GOP’s column, but still gave Speaker Pelosi a massive 257-seat majority to work with. Nobody had a wave in 2020’s remarkably narrow Democratic trifecta, so we won’t see this effect again in 2022.

This happened twice, both in non-wave elections: in 1960’s split decision, where the Democrat, Kennedy, won the White House but the GOP gained 22 seats; and in 1952, where Republicans narrowly won the House but lost the popular vote by a hair (thanks to the Solid Segregationist South’s deep loyalty to the Democratic Party).

Compare Herschel Walker’s poll numbers to Brian Kemp’s, or J.D. Vance’s to Mike DeWine’s, or Blake Masters’ to the last conventional Republican to win a statewide nomination in Arizona. (Doug Ducey? Mark Brnovich?) These “unconventional” GOP candidates are abysmally underperforming their more conventional, higher-quality counterparts, and the Republicans may well win the national popular vote yet lose the Senate because of it.

Dave Wasserman of the Cook Political Report has the GOP at 234 seats (+21), Larry Sabato and Co. have the GOP at 237 seats (+24), and Inside Elections is paywalled but I gather they’re in that zone, too.

Though I have some doubts about The Economist. They suspiciously made substantial programming changes in their model less than two weeks before the election, although at least they disclosed it.

52 seats is the magic number because Democrats need 52 Senate seats to bypass Sens. Manchin (D-WV) and Sinema (D-AZ), who support the filibuster.

Or New Hampshire might just be counting slow, which it does sometimes. North Carolina too, for that matter!

When parties actually publish internal polls, it is almost exclusively for propaganda purposes. Most internal polls show unexciting or actively bad results, so the parties don’t release them. As a result, a good rule of thumb is that any published internal poll is biased, and you should adjust the margin 7 points in the opponent’s direction. So, if Bob’s campaign releases an internal poll that shows Bob winning by 1 point, you should mentally treat that as “Bob is losing by 6 points.” Unpublished internal polls, by contrast, likely have only a modest partisan bias.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WGm3MDo62wY