Greta Thunberg, Pretender to the American Throne

What to do when your President isn't the President

EDITOR’S NOTE: This post was scheduled to publish on December 17, the day the Electoral College actually votes, but, for reasons unknown to me, Substack published it early. Perhaps I clicked something wrong. Special preview, I guess!

The electoral college is voting today, so let’s celebrate with a weird legal hypothetical with absolutely no relevance to anything.1

Suppose the year is 2032, and the United States holds a presidential election.

(This is, admittedly, not a great stretch of the imagination, but indulge me, because it’s about to get weirder.)

It’s a chaotic election! Under the twin pressures of intense polarization and ongoing realignment, both major parties finally fracture. “Decision 2032” becomes the first election since 1860 with four viable presidential candidates: the Republican, the Democrat, the Knothead, and the Progressive.

They go at each other hammer and tongs. All accuse one another of flagrantly violating the Constitution; all seem correct about that. None gets a clear lead on the others, and the waters are further muddied by several third-party campaigns.

(Well, fifth-party campaigns.)

When all the votes are counted, the Progressive Party’s ticket, starring climate activist Greta Thunberg and running mate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, has won the most votes: 30% of all votes cast. Better yet, Ms. Thunberg’s votes are distributed with near-perfect efficiency. She wins every single state except Montana. Montana votes for the Knothead candidate, Tucker Carlson. (In most other states, Tucker finishes second.) Greta Thunberg becomes the presumptive2 president-elect; “AOC” becomes the presumptive vice-president elect.

There is an obvious problem with this: Greta Thunberg is not qualified to be President of the United States. She is a 29-year-old Swede. The U.S. Constitution provides:

No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any Person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.

Ms. Thunberg, whatever her other qualities, is none of these things.

As a result, many states attempted to knock her off their ballots. In most states, courts intervened to reinstate Thunberg, arguing that states lack the authority to adjudicate her qualifications and that only Congress could supply such a process. In the few states that succeeded in removing Thunberg from the ballot, she won anyway, because her supporters staged successful write-in campaigns.3

In the end, she won the plurality of votes in 48 out of 50 states.

Yet, by the text of the Constitution, she can never be President.

What happens now?

The Electoral College

The first firewall against an unqualified presidential candidate is supposed to be the electoral college. The electors were supposed to meet in their state capitols with relatively open minds, consider the candidates, reject disqualified candidates, and, after some debate, vote for the best candidate.

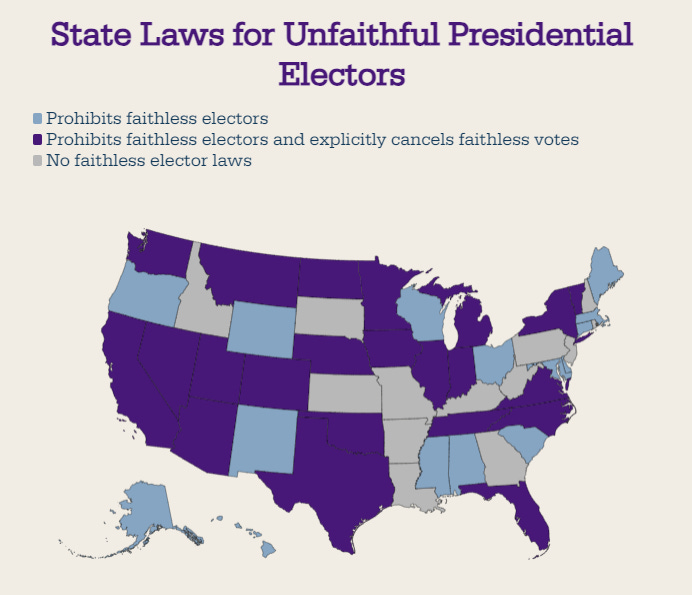

However, as De Civitate has explored at considerable length, the electoral college system broke down the very first time it was used. It has never functioned as intended. It is no longer capable of filtering out unqualified candidates (if, indeed, it ever was). In addition to the fact that presidential electors are hand-picked by the political parties for their loyalty and discipline, many states have passed laws coercing their electors to vote according to the state popular vote:

As of today,4 320 electoral votes are voidable if the elector is “faithless.” For example, if an elector in Minnesota stands up and says, “Well, yes, Greta won the popular election here, but she isn’t actually qualified to be president, so I am voting for Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez for president, and here is my ballot,” he loses office by that very act and is no longer an elector. The other Greta electors must then replace him. This process continues until Minnesota has cast all 10 of its electoral votes for Greta Thunberg. A hundred, a thousand Greta electors could protest that they can’t actually vote for a disqualified candidate, and it will not matter: Minnesota will churn through a thousand-and-ten electors, or a million-and-ten electors, in order to secure ten electoral votes for Greta.

That is because there is no provision in state law saying, “…unless the candidate is disqualified by dint of the Constitution.” The Uniform Faithful Presidential Electors Act, adopted by Minnesota along with many of the other “voiding” states, expressly avoids the problem of the presumptive president-elect becoming dead, disabled, or disqualified after Election Day but before Electoral College Day. The UFPEA’s authors suggest:

A state may choose to deal separately with one or another of these possibilities.

They didn’t.5

If every elector in every state stood up and refused to cast their ballot for the disqualified Greta Thunberg—even on pain of imprisonment, as in New Mexico—Greta is still guaranteed well over 270 electoral votes, sufficient to win the presidential election. She inevitably becomes the president-elect. (AOC becomes vice-president elect.)

The Joint Session: January 6, 2033

The votes from the electoral college are mailed to Congress, which gathers just after the new year to formally count them and certify the election.

The Constitution provides, in Amendment XII:

The President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted;

The person having the greatest number of votes for President, shall be the President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed;

This used to be an obscure electoral codicil known only to weird nerds, but then suddenly everyone became very well-educated about it after the last election. The January 6 Capitol Riot: big win for civics teachers!

The Constitution also provides, in Amendment XX:

If a President shall not have been chosen before the time fixed for the beginning of his term, or if the President-elect shall have failed to qualify, then the Vice President-elect shall act as President until a President shall have qualified.

Congress’s thinking here seems to have been that, if a president-elect were under the age of 35 at the start of his term, he would gallantly stand aside and allow the vice-president to hold his office until he matured. Just a couple years after Amendment XX was proposed (in 1934), a young man named Rush Holt was elected to the U.S. Senate from West Virginia, even though he was only 29. (U.S. Senators must be 30, according to the Constitution.) Holt did indeed stand aside and left the seat empty until he was able to take the oath of office just after his June birthday.

This, perhaps, was the kind of norm-following law-obeying bonhomie that Congress expected in 1930. However, we no longer have norm-following law-obeying bonhomie, so, as January 6 approaches, you may rest assured that Greta Thunberg and her Progressive Party do not politely stand aside until everyone agrees that she is qualified to be President.

In fact, Thunberg’s campaign starts to argue that she is qualified. Her legal team argues that we have a “living constitution,” which “embodies our binding values,” and that the age and natural-born citizenship requirements only embody the “value” that an incoming President must be mature enough and educated enough to govern and that the President must identify strongly with America. On this narrow interpretation of the qualifications clauses, Thunberg is qualified. Furthermore, they argue, the qualifications clauses are discriminatory, and were therefore implicitly repealed by the ratification of the Equal Protection Clause in 1868.

Neither of these arguments convince very many people, but they provide just enough of a fig leaf to those who want her on the throne. So, since she is not standing aside like young Rush Holt, someone must take positive action to prevent her certification to the presidency.

The obvious place to stop her certification—indeed, the only place to stop her certification—is the joint session on January 6. This is the only time America’s elected national officials are gathered together before the presidential election is certified. They are capable of engaging in reasoned debate and issuing legal decisions. They are capable of rejecting invalid electoral votes, and they have done so in the past. Since their certification process is vested in Congress by the Constitution, not even the Supreme Court can directly interfere in it. To stop the unqualified president-elect, Congress must act on January 6, 2033.

This will not be easy.

Under the Electoral Count Act,6 members of Congress who wish to object must do so on the grounds that the votes of Thunberg electors were not “regularly given.”7 However, the states followed legal procedure. The electoral college followed legal procedure. The state certifying authorities all followed legal procedure. Those entirely legal procedures yielded an illegal president-elect, but the procedures were followed. Someone who wanted Thunberg to be president might argue that this means the votes were regularly given, so any objections would be unlawful.

Of course, most scholars agree8 that an electoral vote for a constitutionally disqualified candidate is not “regularly given,” and therefore should be objected to and not counted. Congress’s own decision in 1872 to throw out Horace Greely’s electoral votes (Greely was disqualified because he had died in late November) seems to confirm that Congress can (and must) object to electoral votes cast for disqualified candidates. However, when has a Congressman ever stopped making a plausible-sounding argument that gets him out of casting a tough vote just because the argument happens to be wrong?

There are likely to be many Congressmen eager to avoid casting a tough vote on Greta Thunberg’s qualifications.

Thunberg’s “victory” in the popular vote (with 30%) also delivered her Progressive Party 40% of the seats in both houses of Congress. Tucker Carlson’s Knotheads got 30% of the seats, Democrats won 20%, and Republicans just 10%. We may safely assume that everyone in the Progressive Party will do everything in their power to avoid having to directly vote on President-Elect Thunberg’s qualifications. Nearly all Congressmen do what they must to protect their political parties, no matter how humiliating or asinine, but they don’t enjoy it. Democrats are not so loyal to Thunberg, and many of them have said publicly that they believe Thunberg is disqualified. However, the only other candidate to win electoral votes in this election was Tucker Carlson.

If the Democrats, the Knotheads, and the Republicans did join forces to reject all of Thunberg’s electoral votes, the final electoral tally would be Tucker Carlson with 4 votes to everyone else with 0 votes. Since Tucker won 100% of the valid electoral votes, he would be elected president.9 This would be both legally and morally correct. The Constitution is not a suggestion, and everyone in Congress swore a solemn oath to it before God. But most Democrats would sooner slit their own throats than make Tucker Carlson the President of the United States. Therefore, most of the Democrats will almost certainly find some way to justify voting to uphold Thunberg’s electoral votes. Partisanship always beats the Constitution. It says so right there at the end of Article VI!

To be heard at all, objectors must gather support to lodge the objection. After the abuse of the objection process on January 6, 2021, Congress raised the threshold for filing objections. It used to be that one member of the House and one member of the Senate could jointly file a written objection to one or more electoral votes from a specific state. The threshold is now twenty senators and eighty-seven Congressmen (20% of both houses), all of whom must sign the written objection. This is not a walk in the park, even if 20% of Congress fully agrees with you. If opponents are certain they’re going to lose anyway, they often don’t want to force a vote if it will draw ire from their constituents or make them look too partisan.

Another, more mundane reason why even Thunberg’s opponents might want to avoid a floor fight over her qualifications is the sheer time commitment. Under the Electoral Count Act, each objection takes two hours to resolve (plus a few minutes of walking-around time, as the joint session reforms after each debate). Objecting to Greta’s electoral votes in forty-nine states would therefore require roughly one hundred hours. Assuming Congress works twelve hours a day before taking a recess, that’s eight days… but, under a provision of the Electoral Count Act, Congress is legally barred from taking any more recesses once five days have elapsed, so, after five 12-hour days, Congress would have to sit a marathon 40-hour joint session with no more breaks.10 Every Congressman and Senator who signed an objection paper would be signing up for that, and, forgive them, they’re human, lots of them are ridiculously elderly, and they don’t enjoy crushing legislative marathons.

The Joint Session is the appropriate venue for fighting Thunberg’s certification, but, because of these headwinds, Thunberg’s electoral votes would very likely survive the joint session and be counted as valid.

At the end of the joint session, by law:

…the votes having been ascertained and counted according to the rules in this subchapter provided, the result of the same shall be delivered to the President of the Senate, who shall thereupon announce the state of the vote, which announcement shall be deemed a sufficient declaration of the persons, if any, elected President and Vice President of the United States.

Once this has happened, Thunberg is officially certified as president-elect, and there is nothing anyone can do to stop it.11 President-Elect Greta Thunberg, despite being clearly ruled out by our Constitution, will be inaugurated on 20 January 2033.

At no point here has Greta herself actually claimed to be qualified. Neither the Constitution nor any statute forces her to prove her qualifications, or even to swear that she is qualified. Most Americans think she is disqualified, and most Americans did not and do not want her to be President. (Some prefer her to Tucker Carlson, of course.) Her campaign is making a bad-faith legal argument that she is qualified, but that argument has not been upheld by any court. It probably hasn’t even been upheld by Congress, either, since it is unlikely that the opposition was able to get enough signatures on an objection to force a vote. The Constitution’s qualification clauses are clear, but they have not been allowed to get a word in edgewise!

The current legal process for installing a president assumes that the presumptive president-elect is qualified. It provides no workable mechanism for stopping her inauguration if she isn’t qualified, even if (nearly) everybody knows she isn’t qualified.

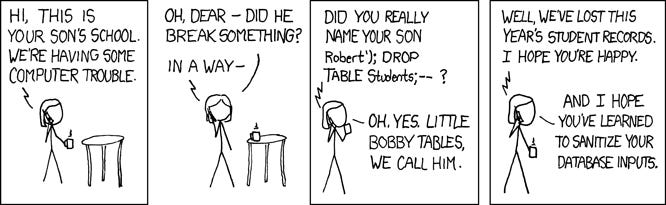

Computer programmers will recognize this pattern, because it happens to us all the time: the Constitution and its agents have forgotten to sanitize its inputs.

The De Facto President

Once Thunberg is sworn in and starts giving orders as chief executive, we find ourselves in an interesting legal position.

Thunberg cannot be President. In fact, since the Constitution is the law of the land, she is not the President. Even if every single person in the United States except Tucker Carlson agrees that she is the President, Tucker Carlson is simply correct and everyone else is simply wrong.

However, although Thunberg is not and cannot be President, she is in unobstructed possession of the White House. She is surrounded by the insignia of office; she discharges its duties and powers, under color of law, in good faith, and in full view of the public; the proper legal process was followed to install her; and that process did not give her the appearance of an pretender.12 She has “the acquiescence of the people and the public authorities and has the reputation of being the officer [s]he assumes to be.” She is the de facto President of the United States.

That matters a great deal, because the U.S. courts have frequently ruled, for well over a century, that the acts of a de facto officer of the United States must be treated as valid:

For the good order and peace of society, their authority is to be respected and object until, in some regular mode prescribed by law, their title is investigated and determined. —Norton v. Shelby County (1886)

There is a name for this kind of “investigation”:

Quo Warranto

As we discussed earlier this year:

The writ of quo warranto (“by what right?”) has been used for more than eight centuries to challenge the qualifications of office-holders. As an ancient writ descended from the England’s “common law,” the cause of action quo warranto was broadly recognized as being available even when not spelled out by statute, unless expressly extinguished. However, each state had slightly different rules about who could seek it and who could grant it.

In early American law, the quo warranto was often the only way to oust a public official who held office illegitimately. As the Minnesota Supreme Court put it in 1860’s Parker v. Board of Supervisors of Dakota County (emphasis added):13

The acts of an officer de facto who comes into office by color of title are valid so far as the public and third persons are concerned until he is ousted by quo warranto. (Blackwell on Tax Titles, pp. 116, 117, 118, and cases there cited.) This principle has been settled by an uninterrupted series of judicial decisions, and does not require the citation of authorities to prove it.

Early American case law expressly prohibited “collateral attacks” on officers’ qualifications.14 In other words, you could not raise the issue of an officer’s right to hold office in an unrelated lawsuit. For example, you could not argue that your criminal conviction was void just because the judge in your case hadn’t followed the right procedure when he was appointed. These were all “collateral attacks” and they were all considered invalid. You had to pursue a direct attack: quo warranto.

That wasn’t always the easiest thing in the world, either, since most state and federal laws limit who is allowed to file a quo warranto. For example, under the District of Columbia’s demi-federal quo warranto statute, §16-3500, the only people expressly allowed to start a quo warranto action are the Attorney General of the United States or the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia. (Both are appointed by the President and are therefore exceptionally unlikely to ever start a quo warranto against the President.)

If these officers refuse to act, an “interested person” may apply directly to the court for leave to file. The D.C. Circuit has interpreted the meaning of “interested party” narrowly. At most, an “interested party” might be someone else who ran for President in the same election. Other cases suggest, even more narrowly, that only someone with an actual claim to the presidency counts as an “interested party” under this statute… some some random fifth-party schmuck can’t hack it.

Some cases even indicate that there is no “interested party,” that could possibly qualify under this statute under any circumstances, an interpretation that effectively deletes §16-3503 from the law!15 Personally, I think that’s such an absurd misinterpretation of the case law they cite that we must assume the misinterpretation was deliberate. This happened in 2012, and the very left-leaning D.C. Circuit was clowning on idiotic, self-represented right-wing nutbars who were trying to prevent Barack Obama from taking office because they believed Obama was Kenyan. It is easy to clown on idiot litigants, but please remember, judges, that the precedents are binding all the same, and these particular precedents you wrote while clowning have rendered the quo warranto remedy, at best, questionably accessible.

So Tucker Carlson is sitting over here really smarting hard because he just lost the presidential election to someone who not only literally can’t be President, but who 70% of Americans voted against. Can he file a quo warranto to turf her out?

Maybe. The D.C. Circuit could allow this if they determined that the second-place finisher in the presidential race qualified as an “interested party.” If they did, then Tucker could press the case in court. Greta Thunberg would be forced to appear and defend her qualifications to hold office. Since she obviously isn’t, any competent lawyer would make short work of her. Soon enough, the court would issue an order declaring Thunberg’s presidency invalid and (therefore) over, effective immediately.

On the other hand, they might not allow it. After all, Tucker Carlson is a rival presidential candidate, but he is not the legitimate claimant to the Presidency. Yes, he finished second in most states’ popular elections, but, legally, those elections don’t matter. Yes, if Thunberg’s 534 electoral votes had been thrown out much earlier, Carlson would have won the electoral college. However, that didn’t happen, so Carlson can’t claim to have actually won the electoral college. So who is the legitimate claimant to the presidency?

The Twentieth Amendment told us that, if a president-elect isn’t qualified, the second-place finisher isn’t the guy who becomes president. The Vice-President becomes acting President instead.

In other words, the legitimate claimant to the presidency is not Tucker Carlson. It’s Vice-President Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez. If the D.C. Circuit confirmed its prior suggestion that only the legitimate claimant counts as an “interested party” under the quo warranto statute, then only Vice-President Ocasio-Cortez would be capable of filing a quo warranto without the support of the Attorney General. AOC, who is obviously a strong supporter of her own running mate, is never going to do that.

For the same reason, Tucker might not be very inclined to pursue a quo warranto against Miss Thunberg at all. Weird nerds like me care a great deal about whether the presidency actually has legal title to the office, and are willing to go to fairly extreme lengths to see to it that the Constitution is followed. A normal person, on the other hand, might simply look at the practical consequences. Even if Tucker succeeded in this difficult, expensive quo warranto process, he wouldn’t become President. All he’d be doing is trading President Greta Thunberg for President Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez. Is that worth it? Probably not.

Collateral Attack

As I said before, early American law prohibited collateral attacks on a de facto officer’s title. However, in the judicial revolutions of the 20th Century, many ancient doctrines were eroded, and this was one of them. Starting in 1962’s Glidden Co. v. Zdanok, the Supreme Court began to blow big exceptions in this traditional firewall.

Glidden argued that the rule against collateral attack only forbade “merely technical” nitpicking of an officer’s qualifications, and that collateral attack should be allowed “when the challenge is based upon nonfrivolous constitutional grounds.” The Glidden ruling16 allowed litigants to collaterally challenge the authority of the judges presiding over their own cases—the central thing forbidden by the traditional “no collateral attacks” rule!17 This exception has been widened further in subsequent cases like Ryder v. United States (1995) and Nguyen v. United States (2003), to the point where, in 2014’s NLRB v. Noel Canning, a case about technically deficient appointments that “should” have been all about collateral attacks under the de facto officer doctrine, the Court’s final opinion did not even deign to mention the issue.18 As Taylor Nicolas put it in a recent paper, “[T]he collateral-attack distinction has faded over time, and collateral attacks on authority are now commonplace.”

This presents an opening… maybe.

The (legitimate) President has broad legal authority, given to him by Congress, to impose tariffs at his discretion. Obviously, de facto President Thunberg will use this power to place tariffs on anything with a carbon footprint, starting with automobiles and automobile components. If you’re a car manufacturer, you’re injured by that tariff, so you have standing to sue. You might try the traditional arguments in a lawsuit against executive action: the President is misinterpreting the statute, the tariff didn’t follow the proper administrative procedures, etc. etc., so the tariff violates the law. With a 29-year-old Swede in the Oval Office, though, you might try another approach: you might add that, even if the tariff is legal, she can’t impose it, because she isn’t President. Only AOC can impose these tariffs!

If they follow recent precedent, or care about giving effect to the Constitution, it seems likely that the courts would allow this challenge, since it goes directly to a “nonfrivolous constitutional issue.” On the other hand, what if President Thunberg’s approval rating is pretty high? Or the courts see other advantages in staying on her good side? Or the courts are just gun-shy about literally overturning the result of a presidential election and ordering the installation of a new president? If the courts don’t want to deal with this, the de facto officer doctrine’s traditional rule against collateral attack provides them with plenty of cover.

There may be other paths to challenging a de facto president’s legitimacy,19 but they all seem to end the same way: there are legal openings, but the courts have plenty of ways to close them if they want.

The Asterisk President

All told, then, I am not terribly optimistic about dislodging de facto President Thunberg from office. The road to challenging her is fraught, expensive, and “winning” only puts her running mate in charge of the country instead. Therefore, unless Michael Stokes Paulsen comes up with something unexpected in his secret underground law lab, she is likely to serve a full four-year term and run for re-election facing no serious legal obstacles.

This is not because any competent legal body considers the evidence and rules that Greta Thunberg is a 35-year-old natural-born American citizen qualified for office. It’s not even because anyone rules in favor of Thunberg’s silly argument that the Constitution’s “thirty-five” doesn’t really mean “thirty-five.” Instead, every competent legal body simply avoids the question, either by defect,20 by design,21 or by abuse of discretion.22 Thunberg remains de facto President because nobody is both able and willing to confront her about it.

For you, the random citizen, there isn’t much you can do about that. The Constitution could not be clearer: she is not the President. Her silly fig-leaf justification for her usurpation of the presidency does not suddenly become more convincing just because she got away with it. Yet she still has the nuclear codes. Congress sends its bills to her. She conducts our global diplomacy, and she’ll be spending your tax dollars. If you’re in the military, the orders she gives your top generals are all technically illegal, but the orders your immediate superior gives you as a result are not.

Of course, you can put an asterisk next to her name to your heart’s content. When the 2036 election comes around and people start wondering who the 50th president is going to be, you can (and should) annoyingly correct them: “49th president! The presidency is currently sede vacante!” For the first time in American history, you are justified in being one of those annoying people who gets a bumper sticker that says, “Not MY president!”

But you still gotta pay your taxes. You still gotta follow the laws she signs.

We simply haven’t designed a system that can cope with this. The Constitution’s process is too vague to be enforced. Congress filled in the details of that process, but forgot to deal with this edge case. Voters never care about arcane legal rules when their wages are down and the price of milk is up. Courts are wary of “inserting themselves” into the democratic process, and have plenty of excuses to avoid deciding cases if the answers might cause “chaos.”

So, alas, when push came to shove, it turned out that the Constitution’s Qualifications Clauses aren’t laws. They’re only suggestions. The American People are free to disregard those suggestions. In the 2032 election, a stark minority (30% of all voters) were able to override the Constitution’s provisions for the other 70%.

That’s the system. It’s a little buggy. It would be nice to patch it up, but the software is full of much bigger issues, the devs haven’t released a patch in thirty-two years, there’s no sign they plan to rouse themselves to action anytime soon, and no sign the People are going to make them.

Donald J. Trump, Pretender to the American Throne

Obviously, this was never about Greta Thunberg. I’m sure you all figured that out a long time ago.

There is a strong prima facie case that Mr. Donald Trump is constitutionally unqualified to hold the office of President of the United States, because he engaged in a treasonable insurrection on January 6, 2021. Under Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment, he is disabled from holding office, just as surely as a young foreigner like Greta Thunberg is disabled from holding office.

I have made that case before, and the comments section got pretty lit the last time I brought it up, so I will not waste your time by repeating the arguments again.

Just as our hypothetical Thunberg made fig-leaf legal arguments defending her qualifications, the actual Donald Trump has made fig-leaf legal arguments defending his qualifications. Some find those arguments sincerely convincing. (Some, no doubt, would find Thunberg’s arguments sincerely convincing, too.) I do not.

Moreover, there is substantial legal evidence that the prima facie case has legs:

The House of Representatives voted to impeach then-President Trump on a charge of insurrection (among other things). The motion carried by a simple majority, but won bipartisan support, with 10 Republicans voting yes (and 4 Republicans refusing to cast a vote).

The U.S. Senate tried the case. Although it seemed probable at the time that the necessary supermajority (two-thirds) of the Senate agreed that Trump had committed insurrection, they acquitted him on a technicality: by the time the trial ended, Trump had left office. Many Republicans argued (bolstered by arguments from conservative legal theorist J. Michael Luttig23) that a Senate impeachment trial cannot convict someone who has already left office. This determined the vote of (at minimum) minority leader Mitch McConnell.

Despite that technical point, a majority of the U.S. Senate, including 7 Republicans, still voted to convict Trump of insurrection. That fell short of the two-thirds required to secure the conviction, but it also shows this theory is far from frivolous!

Some people argue that there was no insurrection on January 6. The only court to issue a final judgment on that question24 disagrees: in State of New Mexico ex rel. White vs. Couy Griffin, a private citizen named Marco White brought a quo warranto action25 against Couy Griffin, a participant in the J6 riot who also served as a member of the Otero County Board of County Commissioners. The court ruled that an insurrection had occurred on J6, that Griffin (who did not breach the Capitol but did access a restricted area) was a participant in that insurrection, and that Griffin was therefore constitutionally deprived of office.

The New Mexico Supreme Court affirmed all these holdings.(UPDATE 6 January 2025: My recollection was wrong. The New Mexico Supreme Court affirmed on technical grounds, without reaching the holdings. I get what I deserved for not double-checking my sources!)Some people argue that President Trump did not engage in that January 6 insurrection. The only three courts to directly address that question disagree. In Anderson v. Griswold, the Colorado district court held a 5-day trial (most trials in that area last only 2 or 3 days), during which both sides were able to call witnesses, present evidence, cross-examine the other side, and have other Perry Mason-style trial fun. The court ruled that, by clear and convincing evidence presented at the trial, there was indeed an insurrection on January 6, and that Donald Trump had engaged in that insurrection. The Colorado Supreme Court affirmed this judgment, and furthermore concluded that Trump was therefore disqualified. An Illinois state circuit court agreed. (So did the Maine Secretary of State, for that matter, but she is not a court, and the reviewing court deferred judgment.)

The U.S. Supreme Court, in Trump v. Anderson, dodged the question. They did not overturn the findings of either Colorado court. Instead, they ruled that, while the Colorado courts were free to determine whether Donald Trump engaged in an insurrection for state-law purposes (which they did), they were not free to rule that he was disqualified, because only a legal procedure established by Congress—apparently meaning the federal quo warranto statute—could make that ruling. This was not an affirmation that the Colorado courts got it right… but it wasn’t a rejection, either. It was a dodge.

Thus, it remains the case that every court that has squarely considered the question of the J6 insurrection has come out the same way: “yep, insurrection.” So did majorities of both houses of Congress. I have closely scrutinized the evidence and the arguments on both sides, and I agree with their conclusions.

Nevertheless, the coming legal drama over Trump’s qualifications is likely to end much like Thunberg’s—with a whimper—for most of the same reasons.

Every member of Congress should object to every electoral vote cast for Trump. The evidence is persuasive, the Constitution is not a suggestion, and they have each sworn an oath. Objecting is both legally and morally correct. However, even if they somehow succeeded, they wouldn’t get President Vance, but President Harris. Most Republican Congressmen hate Harris so much (for good reason!) that they’d rather eat the Constitution and burn the excrement than hand her the White House on a point of principle. Even the Democrats are (understandably) terrified of looking like massive hypocrites if they (validly) object to Trump’s electoral votes after their (over-the-top) performative outrage over Republicans’ (invalid) objections to Biden’s electoral votes four years ago. The courts, for their part, have strong motives for avoiding involvement and plenty of excuses to do so.

Indeed, my greatest ambition, at this point, is not even to expel soon-to-be de facto President Trump from office. At this point, I just want to force a court of law to issue a final, binding ruling on Trump’s eligibility to serve as president.

I admit, it is possible that I would lose that case! For instance, the “officers of the United States” argument pressed by Josh Blackman and Seth Barrett Tillman is not compelling but it is pretty plausible. I could see an honest group of judges ruling that Trump is exempt from Section Three because he was never an “officer of the United States,” and therefore qualified to serve another term.

Still, even a clear defeat for my position would be preferable to what we actually have: an entire federal system refusing to confront the president-elect’s qualifications, reducing an important provision of the Constitution to mere suggestion. If the courts, or even Congress, directly confronted the question and told me, definitively, that Trump is qualified, I would argue with the evidence, but I would accept him as the lawful president, just like Al Gore accepted George W. Bush’s presidency after Florida 2000.

But if the law isn’t even going to look me in the eye and answer the damn question, the conscientious citizen must draw his own conclusions. Trump will never be the President, because he cannot be the President. You should not regard him as the President. You should start practicing that asterisk.

I stayed up late on Election Night. (I always do.) The very last thing I did before going to bed was to send an email to a contact who was involved in last year’s lawsuit to remove Donald Trump from the ballot:

A few days later, I got a reply: my contact complained that the quo warranto statute is unusable (pretty much for the reasons I described above); that the U.S. Supreme Court has made clear it will avoid “interfering” in an election by hook or by crook so what’s the point of trying; and that he’s gotten out of this area of law anyway. The interest groups have moved on to greener pastures.

Today, the electoral college votes. It will fail to stop Trump’s de facto election, just as it would fail to stop Greta’s.

Eventually, someone’s going to notice that this means the Twenty-Second Amendment is just a suggestion, too, and run for a third term. Maybe it’ll even be Trump!

So it goes.

CORRECTIONS 15 December 2024: My friend Daniel Pareja pointed out several factual errors, now corrected in the main body of the article. 20% of the House is ceiling(435/5) = 87, not ceiling(538/5) = 108. Incredible brain fart. Since Raphael Warnock, Jon Ossoff, Alex Padilla, and President of the Senate Kamala Harris had all taken their seats by the time of the impeachment trial, Sen. Mitch McConnell was the minority leader, not the majority leader. Finally, Colorado’s courts were not the only courts to directly answer the question of Trump’s qualifications, because an Illinois court agreed with them. (He also pointed out that Maine’s SecState had ruled on it, too, so I slipped that in as well.)

READER: “Hm, that seems like a suspiciously specific denial!”

I say “presumptive” because the popular elections held on the first Tuesday in November do not actually elect a president, but rather presidential electors. The presidential electors vote for president in the third week of December, and, legally speaking, they are the first group to do so. The electoral college creates the president-elect.

This is sort of like how the party conventions in summer create the presidential nominees. Until the convention, there is legally no nominee, even though there is (virtually) always a presumptive nominee by the time the primaries end. The distinction between a presumptive nominee and an actual nominee is very slim, but, as we saw in this year’s Biden-Harris summer switchout, it is sometimes decisive!

In some states, write-in candidates must be registered, and must be qualified in order to be registered, and write-in votes for a candidate known to be disqualified are void. Therefore, the write-in strategy could not work in every state.

I expect more such laws to be passed between today and 2032. This is because, until recently, many people (including me) believed they were unconstitutional, which likely prevented them from passing in some states. However, the Supreme Court affirmed their constitutionality in 2020’s Chiafalo v. Washington, so that obstacle has now been removed.

It is possible that some states dealt with the possibility of an unqualified person winning the state’s popular presidential election. I did not do an exhaustive survey. However, none of the states I have looked at bothered.

Wisconsin wisely added a law saying, “A presidential elector is not required to vote for a candidate who is deceased at the time of the meeting,” so at least they had the presence of mind to deal with a dead candidate, but had nothing to say about disability or disqualification.

That’s as close as I found. Many don’t even have provisions covering the death of the candidate. Congratulations to whatever state out there, if any, actually has a law dealing with the possibility of a disqualified individual winning the local popular presidential election.

…as recently amended by the Electoral Count Reform Act of 2022…

Specifically, the law provides:

The only grounds for objections shall be as follows:

(I) The electors of the State were not lawfully certified under a certificate of ascertainment of appointment of electors according to section 5(a)(1).

(II) The vote of one or more electors has not been regularly given.

See Derek T. Muller’s Electoral Votes Regularly Given in the Georgia Law Review Vol. 55 No. 4, or, if you can find it, Beverly J. Ross & William Josephson’s The Electoral College and the Popular Vote, in The Journal of Law and Politics, September 1996, which is much more thorough.

Per the Twelfth Amendment, to win the electoral college outright, a candidate must win both “the greatest number of votes” and “the majority of the whole number of electors appointed.” If no candidate wins a majority of the electoral college, the election is thrown to the House of Representatives for a contingent election.

According to the Electoral Count Reform Act of 2022, if Congress successfully objects to and throws out an electoral vote, that electoral vote no longer counts as part of “the whole number of electors appointed.” Thus, if Congress threw out all 534 of Greta Thunberg’s electoral votes, the number of electoral votes Tucker Carlson needs to win to become President would be, not 270 out of 538, but 3 out of 4.

Some legal thinkers disagree with the Electoral Count Reform Act on this point. They believe this provision is unconstitutional. According to them, “the whole number of electors appointed” means all 538 electors, even if 534 of their votes are rejected. (In nerd parlance, they think that rejecting the electors does not “reduce the denominator.”) Tucker still needs 270 electoral votes, according to this theory, but he only has 4, so he loses and the election is thrown to the House.

This doesn’t help Carlson’s opponents. When an election is thrown to the House, the House must choose between the candidates who got the most (valid) electoral votes—up to three of them. (That’s what the Twelfth Amendment says.) In this election, however, the only candidate who got any electoral votes was Tucker Carlson. The House must choose between Tucker and there is no second choice.

The opposition would have to either accept Tucker or abstain. They could abstain. This would prevent Tucker from becoming President. Under the Constitution, incoming Vice-President Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez would become Acting President instead. However, the House is constitutionally barred from doing anything else until it elects a President. The opposition could keep AOC in power indefinitely, up to the length of the entire presidential term… but at the cost of the House of Representatives being unable to pass legislation, including budget legislation, for four years. Hello government shutdown. This is probably politically infeasible.

The houses could shorten the debate time per objection, so it wouldn’t always have to take two hours, but it’s not clear to me whether this could be done by majority vote or requires unanimous consent. The Thunberg faction would obviously fight every step of the way, using the exhausting sessions as a way to sap the opposition’s morale while building popular support for Thunberg against Carlson.

Well, maybe Congress could possibly pass a law retroactively repealing this declaration, but that would be legally fraught, would require the cooperation of the sitting lame-duck president, and would never actually happen.

Yes, American law really uses the term “pretender,” although “intruder” is more common.

“Usurper” is also sometimes used, but, other times “usurper” is contrasted with a mere intruder. The intruder acts in good faith “under color of law”. the usurper does not.

4 Minn. 59, 1860 WL 2816, if you wanna be a nerd about it.

As the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts explained in an early case (Fowler v. Bebee, 9 Mass. 231):

That Jonathan Smith, Jun., is sheriff of the county of Hampden de facto, is very certain; but whether he is sheriff de jure, is the question made by the defendants. Mr. Smith is no party to this record, nor can he be legally heard in the discussion of this plea; although our decision would as effectually decide on his title to the office, as if he were a party. This would be judging a man unheard, contrary to natural equity, and the policy of the law. From considerations like these has arisen the distinction between the holding of an office de facto and de jure. […] If an action should be commenced against one claiming to be sheriff, for an act which he does not justify, but as sheriff; or if an information [in the nature of a writ of quo warranto] should be filed, calling on such a one to show cause why he claimed to hold that office; in either case he would be a party; and the legality of his commission might come in question, and meet a regular decision.

This precedent was cited by the U.S. Supreme Court, among others, to help establish the principle that qualifications are not subject to collateral attack.

Of course, that isn’t quite what Fowler v. Bebee says. Fowler v. Bebee says that an officer’s title cannot be attacked unless he is a party to the case. That’s not quite the same thing! It’s possible to launch a collateral attack on an official’s title within a case to which the official is a party! For example, if a federal official sues you in his official capacity for violating some law, and you counter that the official is invalidly appointed and therefore unable to bring the suit, that’s a collateral attack against a named party.

So the “no collateral attacks” rule was actually born pregnant with an exception, and it is thus perhaps unsurprising that the rule started to erode during the 20th century (as we will see later on).

On top of all this is an additional complication: the statute allows the “interested party” to file only after the Attorney General and U.S. Attorney have both “refused” to file themselves. What if they don’t refuse? What if they receive your request, tell you they’ll think about it, and then continue to “think about it” for the next four years until the de facto President’s term ends and she leaves office? Does that constitute a refusal? How long must an “interested party” wait before asking the court to recognize some kind of “constructive refusal”? The statute doesn’t spell it out, and the court in Sibley v. Obama said that it could not act without an actual refusal.

This was pointed out to me in correspondence with a lawyer who has done work in this area who, I believe, wishes to remain anonymous. Hat tip to that lawyer. You know who you are.

As a mere plurality decision, Glidden did not inherently have stare decisis value, but future courts have cited it often enough that it is now a fairly important precedent.

See Ball v. United States, 163 US 662 (1896) and, of course, In re Griffin (1869), which De Civ discussed at great length in January.

The de facto officer doctrine came up very briefly at Noel Canning’s oral argument, but the collateral attack issue did not. It was also mentioned by an amicus or two.

For example, if you’re a state prosecutor, you could file criminal charges against the de facto president. The criminal charges wouldn’t even necessarily need to be serious. (Technically, they don’t even need to be accurate charges filed in good faith, but, obviously, I condemn abusing public office to file unfounded charges against anyone.) The White House would respond by pointing out that long precedent makes a sitting president immune to criminal charges of all kinds.

You, the prosecutor, would then spring your trap: “but she’s not the sitting president, so she’s not immune.” The immunity issue would need to be resolved immediately, before the underlying criminal charges, and would be subject to interlocutory appeal, so you’d only need to keep the case going long enough to get a ruling on whether Thunberg is the valid president. After that, you’d be okay to drop the charges.

(Although, again, I condemn filing criminal charges solely to wring a ruling out of an unwilling judiciary. If you’re going to charge it, you’d better follow through.)

Yet the judiciary can wriggle out of this, too, if it wants! There are several lower-court cases which hold that at least some officers de facto are entitled to all the immunities attached to their usurped offices (Miller v. Filter, 150 Cal.App.4th 652, 667 (Cal. Ct. App. 2007), Sank v. Poole, 231 Ill. App. 3d 780, 784 (Ill. App. Ct. 1992), White by Swafford v. Gerbitz, 892 F.2d 457 (6th Cir. 1989)). A court could extend those precedents to the presidency and rule that, even if Alleged President Thunberg were disqualified, she would still be entitled to criminal immunity, so the charges are tossed out without resolving the question of Thunberg’s qualifications.

For example, the electoral college having its power to challenge Thunberg’s qualifications legislated away in many states.

For example, Thunberg’s Attorney General refusing to support a quo warranto against his nominal boss.

For example, the courts selectively invoking the de facto officer doctrine to avoid overturning the results of a presidential election.

Notably, Luttig himself agreed Trump was an insurrectionist. He was a passionate supporter of having Trump struck from the ballot. He just didn’t think the Senate could convict him once he left office, and those arguments appear to have been completely sincere.

At least, the only court I can think of

New Mexico’s statute is apparently pretty unusual, insofar as it apparently allows private citizens with no other interest to bring quo warrantos.

“Obviously, this was never about Greta Thunberg.” Talk about a twist ending!

There is, I believe, still a factual error in this article that needs clarifying, specifically having to do with New Mexico ex rel. White et al v. Griffin.

As I understand the ultimate disposition of the case, Mr. Griffin, after losing in a trial court in Santa Fe County, had an appeal as of right directly to the New Mexico Supreme Court. However, this right is subject to certain state-law procedural requirements, which Mr. Griffin failed to meet. Consequently, the New Mexico Supreme Court, rather than upholding the trial court's findings on the merits, dismissed Mr. Griffin's appeal on procedural grounds.

Mr. Griffin then appealed to the federal Supreme Court, since such appeals are permitted from state supreme courts (or whatever your state happens to call its highest court for the suit in question, if you're in a state like New York, Texas or Oklahoma) on questions of federal law, and the proper interpretation of Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment and its applicability and adjudication fall squarely within that ambit.

You can see the relevant documents here: https://www.supremecourt.gov/search.aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html/public/23-279.html

Of note is that there were no amicus briefs filed, and the respondents on appeal initially waived their right of response to Mr. Griffin's petition.

The problem Mr. Griffin faced in appealing to the federal Supreme Court is that the state Supreme Court had not ruled against him on questions of federal law, but rather had made a procedural ruling on the basis of New Mexico's civil procedure and quo warranto statutes. (It is perhaps worth noting here that like many states, Colorado and Minnesota among them, New Mexico's rules of civil procedure are effectively just a copy of the federal rules, which probably helps state government lawyers not have to keep two different sets of rules straight, but nonetheless in the New Mexico civil action context of this suit they are a state law, not a federal one.) The holdings on the questions of federal law were only made by the inferior court in Santa Fe County. Consequently there was, technically, nothing on which the state Supreme Court had ruled that Mr. Griffin could appeal.

The federal Supreme Court dismissed his application for a writ of certiorari without comment, some time after deciding Trump v. Anderson.

Ultimately, only the Santa Fe County trial court ever considered the merits of White v. Griffin. Mr. Griffin's error in failing to properly appeal to the state Supreme Court led to a procedural dismissal in that venue, which in turn led to the federal Supreme Court lacking any basis for appellate review, since the state Supreme Court had not ruled on any questions of federal law.

All that said, of course, given the holding in Trump v. Anderson, New Mexico's courts were entirely within their rights to adjudicate whether Mr. Griffin was eligible to hold an office under the state of New Mexico, such as serving on a county board of commissioners. Whether the trial court properly interpreted the law in the context of the events of January 6, 2021 is not something on which any higher court ruled, and indeed could not rule due to Mr. Griffin failing to meet the procedural requirements of New Mexico law.