Worthy Reads: Spookin' Up Your Christmas Party

Worthy Reads for December 2024. Merry Christmas from De Civitate!

Welcome to Worthy Reads, where I share some things that I think are worth your time. It has the rare De Civitate paywall. Everyone gets the first half of Worthy Reads, but only paying subscribers get the second half. (They keep me writing, so don’t begrudge them. They deserve it.) Retweets are not endorsements.

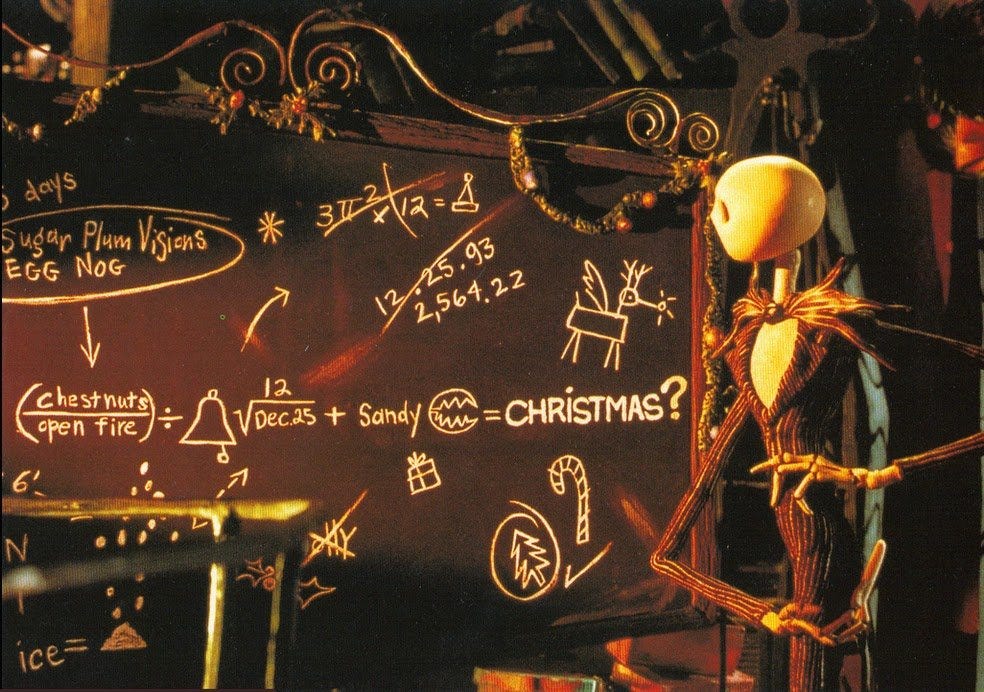

“Why The Nightmare Before Christmas Has a Special Relationship to Us,“ by Owen Cyclops:

some people seem to instinctually take on this movie as part of their personality. i remember going to a girl's room once and she had a nightmare before christmas blanket. "yeah, that makes sense". people wear shirts of it, bumper stickers - all year, not just at either holiday.

this is noteworthy because it's a holiday film that transcends the holidays. this is usually the opposite of what holiday movies do. they're usually especially confined to their seasonal domain. someone wouldn't really wear christmas movie gear in spring, as a general rule. […]

my posit is that the reason this movie has an instinctual resonance in our culture is because jack's experience is the experience of the modern person, here explicated as their experience of the holidays.

this is what christmas is like for the modern secular child… theres this magic space, i want to inhabit it. but its not "of you". its other. its not your world. you don't actually believe in the thing that, at the core, is what it's all about. you are not part of it

But also! “The Nightmare Before Christmas is a Parable for Our Secular Age,” by Nicholas McDonald:

"There's something deep inside of my bones,” Jack sings, “…a longing that I've never known." This malaise (or “emptiness”, as Jack puts it) is present in Jack because he lives in what Taylor calls the “immanent frame”: a worldview that is essentially materialist, and so believes there is no transcendent story or force guiding things. It is a “disenchanted” world. It is also a humanistic world, placing humanity at the center of things: Jack - the figure of humanity in halloweentown - is literally worshipped by everyone. This is what it feels like, Taylor argues, to live in our secular age, even at the very top of the economic food chain. Longings we can’t explain. A growing emptiness. The weariness we feel in a world without meaning. […]

Jack sees the enchantment of Christmas. He even “knows the stories” and “knows the rhymes” and carols - our first allusion to songs and stories about Christ’s incarnation. Like Dawkins, however, Jack experiences this all from the outside. His “bony finger” cannot, as C.S. Lewis once put it, “enter in” and “become part of” the enchantment, because Jack can only comprehend the ornamentation of Christmas, not the story of Christ itself. This scene represents the fruitless task of philosophy in a secular age. Without the Christ, immanent philosophy can only ping-pong between relativism (or more specifically nominalism) and materialism (or more specifically essentialism).

But here is the important character turn. Jack - IMPORTANTLY - never resolves the philosophical tension. He merely decides to announce that he will embody the values of Christmastown blindly - "Christmas is OURS!"

These two closely-related essays were written at about the same time by different authors who apparently reached their similar conclusions independently. They blurred together so completely in my brain that I can no longer separate them, and therefore must share both. They’re worth a full read, amusing even if you don’t buy the thesis. McDonald, especially, has a lot of fun drawing absurd, kabbalistic connections between Nightmare and the Holy Bible, in a hale spirit of “None of this is a coincidence because nothing is ever a coincidence.”

I don’t think this is an explanation for all Nightmare Before Christmas fandom, by the way. My wife loves this movie, for one, and it’s not like she wasn’t going to Christmas Mass. Yet there’s enough to this explanation that fits1 that I think it probably is at least part of the story behind this enduring Christmas classic.

I also think it’s a nice lens for people who have always been baffled by The Nightmare Before Christmas. I know plenty of those, too.

“The National Popular Vote Proposal for U.S. Presidential Elections Undermines Election Integrity,” by Ron Rivest and P.B. Stark:

National Popular Vote (NPV) Interstate Compact [Koza et al., 2024] attempts to provide direct presidential elections in the U.S. without a constitutional amendment, through a binding agreement among "member" states comprising a majority in the Electoral College. The compact is intended to ensure that a majority of Electoral College votes go to the winner of the national popular vote. It does not succeed. …For the foreseeable future, adopting NPV is worse than doing nothing.

One of the sad realities of blogging is that, if you sit on an idea for long enough, someone’s eventually going to write about it instead. I admit, though, I thought eventually someone at National Review would get hold of it, not Ron Rivest.

Ron Rivest is not a law professor. He is not a lawyer at all. He’s a celebrity from the other half of my life: he’s a computer scientist, best known for inventing the RSA public-key encryption algorithm2 and the MD5 hash function used to “fingerprint” files on basically all computers. If you’ve ever purchased anything over the Internet, you probably owe Rivest a thank-you, because he helped make that possible.

I have no idea what drew Rivest to write about the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. The NPVIC is a scheme to effectively replace the electoral college with a national popular vote without a constitutional amendment. The basic idea is simple: instead of forcing presidential electors to vote for the winner of the state popular vote, states that join the NPVIC (by passing a state law) agree to force their presidential electors to vote for the winner of the national popular vote.

The NPVIC goes into effect as soon as enough states have joined it to add up to a combined total of 270 electoral votes.3 That’s a majority of the electoral college. Since all the NPVIC states will vote for the same candidate (the national popular vote winner), this guarantees that the winner of the electoral college will always be the winner of the national popular vote. Currently, NPVIC has eighteen states4 totaling 209 electoral votes (almost all blue states), but it has been stuck trying to convert the purple states it needs to get over the top. Since the national popular vote is popular, NPVIC keeps at it. Eventually, they expect they will gain enough members to go into effect.

Seems simple, right? That’s the problem. It is simple. Too simple.

NPVIC determines the winner of the national popular vote by requiring each state to accept the certified election results of every other state (Article III, Clause 5). It more-or-less has to do this, or something quite like it, because states don’t have the right to meddle in the presidential election processes of other states.

Suppose NPVIC gets up and running. The 2036 rematch between Tucker and Greta leads to a decisive win for Tucker, who is elected 55-45% excluding California. However, after two weeks carefully counting the votes, California’s secretary of state announces that Greta received two billion votes from California, while Tucker Carlson received only six votes. Bolstered by those extra two billion votes, Greta wins the national popular vote. There is no clear mechanism in the NPVIC for someone to point out, “Uh, hey, you know California’s population is just a tiny fraction of that.” NPVIC has no oversight or supervision mechanism. NPVIC simply assumes that state officials and state legislatures will do “the right thing” and report accurate vote totals—including, importantly, the many states that are sure to continue opposing the NPVIC. NPVIC depends on hostile states to freely cooperate.

This is one reason why the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact can not work and never could. In this short paper, Rivest explains a number of related problems, many of which do not rely on deliberate sabotage: instant-runoff counting standards (I admit, I never thought of that one!), election auditing issues (I did think of that one), and of course the strife and suspicion that would spring up between the states if ballot-box stuffing in deep red or deep blue states actually could change the outcome of a close presidential election. States (like my own Minnesota) that sign on to NPVIC are being foolish, and must hope that their dogs never actually catch this particular car. The only way to have a national popular vote has always been to amend the Constitution, abolish the electoral college, and put Congress in full control of our elections. For a variety of reasons, this would be a terrible idea, too—but it would work a lot better than the doomed NPVIC.

“The Hidden Cause of Food Deserts,” by Stacy Mitchell:

Congress responded in 1936 by passing the Robinson-Patman Act. The law essentially bans price discrimination, making it illegal for suppliers to offer preferential deals and for retailers to demand them. It does, however, allow businesses to pass along legitimate savings. If it truly costs less to sell a product by the truckload rather than by the case, for example, then suppliers can adjust their prices accordingly—just so long as every retailer who buys by the truckload gets the same discount.

For the next four decades, Robinson-Patman was a staple of the Federal Trade Commission’s enforcement agenda. From 1952 to 1964, for example, the agency issued 81 formal complaints to block grocery suppliers from giving large supermarket chains better prices on milk, oatmeal, pasta, cookies, and other items than they offered to smaller grocers. Most of these complaints were resolved when suppliers agreed to eliminate the price discrimination. Occasionally a case went to court.

During the decades when Robinson-Patman was enforced—part of the broader mid-century regime of vigorous antitrust—the grocery sector was highly competitive, with a wide range of stores vying for shoppers and a roughly equal balance of chains and independents. In 1954, the eight largest supermarket chains captured 25 percent of grocery sales. That statistic was virtually identical in 1982, although the specific companies on top had changed. As they had for decades, Americans in the early 1980s did more than half their grocery shopping at independent stores, including both single-location businesses and small, locally owned chains. Local grocers thrived alongside large, publicly traded companies such as Kroger and Safeway. …The Robinson-Patman Act, in short, appears to have worked as intended throughout the mid-20th century.

Then it was abandoned. In the 1980s, convinced that tough antitrust enforcement was holding back American business, the Reagan administration set about dismantling it. The Robinson-Patman Act remained on the books, but the new regime saw it as an economically illiterate handout to inefficient small businesses. And so the government simply stopped enforcing it. That move tipped the retail market in favor of the largest chains, who could once again wield their leverage over suppliers, just as A&P had done in the 1930s.

I haven’t banged my anti-monopoly drum here very much lately, because it is an extraordinarily complicated intersection between law and economics, and I do not trust myself to cover it well. This, however, is a short, simple anti-monopoly story—simple enough that I feel confident sharing it. You can make this story much longer (there’s a book called Goliath5 that does so), but it doesn’t change the takeaways.

As a matter of fact, you see this pattern throughout our economy. Wal-Mart didn’t just happen. Mom-and-pops didn’t get wiped out because they just couldn’t compete. Amazon didn’t just arise because nobody else could run a good online bookstore. Wal-Mart, Amazon, and other vast corporations scrabbled for market power, then used their market power to crush their competition. We see different versions of this story over and over against throughout our economy, in areas as diverse as meat-packing, overseas shipping, cheerleading, ammunition manufacturing, and hospital supplies. Firms are very cautious about raising prices for general consumers, because, under the current “consumer welfare standard” for antitrust action, raising prices for consumers is one of the few things that can still trigger antitrust investigations. However, the effects of monopoly are felt in many other ways besides obvious price grabs: depressed small-business formation, wage stagnation, shortages, corporation financialization, our recent bout of inflation, and other woes of the modern economy.

In the 1980s, we decided that corporate America was overregulated. This was true. The Civil Aeronautics Board was a disaster and airline deregulation is one of the most successful policies in history. But we threw out a lot of babies with the bathwater, and one of those babies was American antitrust law. We didn’t even have enough respect for the rule of law to repeal antitrust law. We just used executive authority to rewrite and hamstring it so badly it became a dead letter. This isn’t just bad policy; it’s fundamentally at odds with the President’s duty to “take care that all the laws be faithfully executed.” Conservatives should hate the way presidents of both parties deliberately mangled antitrust law from Reagan through President Trump’s first term.

My favorite thing about the Biden Administration by far, then, was Chairwoman Lina Khan of the Federal Trade Commission. Her aggressive revival of the antitrust laws (already on the books) has started to pay dividends for a restoration of economic liberty. Meanwhile, my favorite thing about Vice-President-elect J.D. Vance is that he is one of the precious few Republicans who recognizes, out loud, that Lina Khan is doing a great job. Matt Gaetz, for all his obvious and totally disqualifying faults, was another, which is why it stung to see him withdraw even though I opposed him: having a real antitrust guy in charge of DoJ would have been a huge win. Hopefully, Vance will have Mr. Trump’s ear on this in the coming term.

Antitrust, more than any other area of law or policy, is capable of delivering the economic freedom that Trump’s voters desperately want, and at a low cost. Unfortunately, the first Trump Administration was dominated by pro-monopolists, and Trump himself seems to adore powerful tycoons who crush their competitors and then jack up prices. I am, therefore, not very optimistic.

Here’s the paywall. Whether you’re free-list or pay-list, thank you for reading this far, and I hope you enjoyed! Below the paywall: DOGE’s prospects, the dust-up over kneeling at the Eucharist, divorce’s unspoken role in our national decline, a hard-to-find H.L. Mencken classic, and the video(s) of the month(s)! Want to read it? Sign up here:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to De Civitate to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.