Many writers propose constitutional amendments in order to demonstrate their fantasy vision of the perfect regime. In this series, I propose realistic amendments to the Constitution aimed not at resolving substantive policy debates, but at improving the structure of the U.S. national government—often by fixing provisions of the Constitution that didn’t work the way its well-meaning authors planned. Today’s proposal:

AMENDMENT XXXI

There shall not be less than one Representative for every thirty thousand persons, and not more than one Representative for every twenty-five thousand persons.

I’m hardly the first person to suggest expanding the House. I will make up for it by being the most extreme. By the end of this article, I hope you’re as extreme as I am.

In the constitutional design, the purpose of the House of Representatives is to represent the will of the People. The Senate isn’t designed for that; nor is the presidency nor the courts. The House is uniquely built to give every American voter their voice in Washington, D.C.. So, if you want to know whether the House is serving its designed purpose, you start by asking one question:

Have you ever met your congressman?

I’ve been represented by four congressmen in my lifetime. I think I saw one of them, once, from a distance. I have occasionally sent them letters—sometimes quick “vote against the bad thing” letters, sometimes very long and thoughtful ones—but I’ve only ever received form letters back. This not a huge shock. My current rep, Angie Craig (D-MN), represents 722,101 people. About half of them (325,472 voters) cast ballots in her last election. If Angie Craig ignored all other congressional work (like legislating, voting, learning, negotiating, attending ribbon-cuttings) and spent an entire 40-hour workweek doing nothing but spending time with the voters (not all her constituents, just the actual voters), each voter in her district would get to have a single 90-second conversation with her once every two years. Since that’s not actually how humans work, Angie Craig (like all congressmen) actually only communicates with a tiny fraction of a fraction of her constituents. Even most active Democrats in our district have probably never exchanged actual words with her. At least, I certainly never spoke to Rep. Erik Paulsen when I was active in the GOP in his district. (He’s the one I think I saw, once, from a distance.)

On the other hand, I’ve met my mayor.

Mayor Dave Napier governs the city of West Saint Paul, Minnesota, a small suburb with a population just over 20,000. (10,601 voted in the last contested mayoral election.) It’s not hard to meet him. I showed up to a “town hall” at the local coffee shop with less than a dozen other attendees. I asked one, maybe two direct questions and received direct answers. If you care to show up to a city council meeting, you can yell at him to his face—the line is very short and he does a really good job projecting calm when someone is yelling at him, which is arguably the key qualification for the mayor of a manager-led city with a strong city council.

Feeling ill? Just lazy? Since the pandemic, you can call in and give the Mayor (and the rest of the council) an earful whenever you want. Email the man a question about the city and he will personally answer you. No staff running interference, no form letter thanking you for your interest and ignoring everything you had to say—you can actually just talk to an elected official and he will talk back to you!1 You, too, can have the ear of a man who holds the actual levers of power! How empowering! How democratic! (In the best sense of that word.)

Now, I happen to think Mayor Napier is an above-replacement-level mayor… but this level of accessibility seems pretty normal for small suburban mayors. When you’re governing 20,000 people, only a handful of whom feel a pressing need to talk to you about pressing issues at any given moment, you just don’t need layers and layers of security fencing around you. You probably haven’t ever met your mayor… but, if you live in a town with a population under 40,000, I’ll bet you could meet your mayor very easily. (You just haven’t wanted to.)2

Your Congressman is currently trying to represent more than thirty times as many people as my mayor, but with far less time in which to do it. She doesn’t have time to answer the actual emails of actual constituents because she’s too busy with her part-time job (that is, being a Congressman) and her actual full-time job: fundraising.

Caaaaaash Money!

Ten years ago, incoming Democrats freshly elected to Congress were instructed to spend 2 hours per day on legislation, 1-2 hours per day meeting constituents… and 4 hours per day in the telemarketing cubicle raising money. Republicans are no better. Former Rep. Rick Nolan (R-MN) reported in 2016 that GOP freshmen in Congress were instructed to spend a minimum of 30 hours a week raising money.

This is very important. They need the money. They each need to wage war for the hearts and minds of 325,000 or so voters, convincing the majority of those voters to get off their couches and cast ballots for them… or, at least, not for the other guy! At that vast scale, there’s only one way to do that: money.

That’s interesting, because, in most elections, money doesn’t matter very much.

In a very small election (say, for president of a 100-member club), a candidate hardly even needs to communicate with her constituents. Her constituents already know her well and have formed a judgment about whether she’s well-suited to the job. They vote accordingly.

In a larger election (say, for president of a 1,000-person university class), not everyone knows the candidate personally, but plenty do. The successful candidate will be able to count on his reputation in this small community, and on his friends to spread the good word about him. The candidate must communicate, but mostly through concrete accomplishments known to all in the community, and through positive word-of-mouth. I’m unaware of any evidence that paid political advertising (chalkings, posters, etc.) has any measurable impact whatsoever at this scale of election.3

In a 10,000-person small-town mayoral election, winning purely by reputation and word-of-mouth begins to break down. The median Facebook user only has about 30,000 friends-of-friends, in total,4 and only a small fraction of them typically live in the same community as the user. That is to say: in twenty-first century America, we aren’t friends with everyone in our town. We aren’t even mutual friends with most of them.

So, at this level, we begin to see money enter the race. In the last contested mayoral election in my town—the most expensive municipal election cycle in town history—the losing candidate spent $9,308. The winner, our current mayor, spent $3,609. Why? Because money buys messaging, and messaging is how candidates communicate with voters now. Still, these are not huge sums. Reputation and word-of-mouth are still doing a lot of work for candidates. Where they fall short, it just doesn’t cost all that much money to communicate with remaining constituents, and you hit the point of diminishing returns pretty quickly. You can see how little money ultimately mattered in our mayor’s race: the challenger spent three times as much as the incumbent—and lost anyway, by a huge margin.

Over in my local state legislative election, 2022’s winning candidate, Isa Maria Perez-Hedges, spent $53,020 (mostly to win her contested primary) while doomed opponent Kevin Fjelsted appears to have spent $0. This was in an election to represent about 40,000 people (twice as many people as live in my small town), but total spending was about four times as high. (Which means the campaign spent more money reaching each constituent more times.)5

These cash totals are nothing to sneeze at. I had to raise $15,000 in a month once and, hoo boy, it was a nightmare. But I can imagine raising $10,000 or so for a mayoral run… or even $25,000+ for a legislative run, especially if I had a couple of years in which to do it. This money is enough to allow each candidate to effectively communicate to voters who don’t know the candidates personally, but it’s not a completely unreasonable amount of money to raise.

Meanwhile, over in the U.S. House of Representatives, the average winning candidate spent $2.79 million on the 2022 election. Even the average loser spent $804,000. That’s an overall average; totals were vastly higher in hotly contested races. My local race was a “hot race,” and spending went over $30 million. The idea of raising that much money is unthinkable to me, and probably to you, too. But that’s what you have to do to win an election on this scale! You’ll notice that not only did Congressional candidates have to spend more because they needed to reach more voters; they also spent much more money per voter.

With nearly a million people in your district, it’s simply impossible to be carried into office by the strength of personal relationships and local reputation. You can’t even know more than a fraction of a fraction of your constituents, much less care about them! You have to forcibly build a reputation out of nothing—by blasting advertisements over the airwaves, over the Internet, and in the voters’ mailboxes.6 Advertising costs money. The money’s gotta come from somewhere.

So, we end up with Congresscritters holed up in fundraising cubicles across the street from the Capitol for half the day, trying to raise enough money to communicate with their own constituents.

It gets worse when you realize where all that fundraising money comes from. Plenty often it’s lobbyists or trade groups who give generously. A legislator who needs their money to keep getting elected can’t afford to alienate them. This puts pressure on him to vote in line with the special interests, even if he stops supporting them. The National Association of Realtors put $12.6 million into the 2022 election, almost evenly split between the two parties. No matter which party won that election, the realtors would be ably represented by candidates who couldn’t afford to go against them.

This is the part where lots of people start worrying about the corrosive effects of money in politics. This is also where those people pitch plans to “get money out of politics” that are silly, unconstitutional, ineffective, or quite often all three. Public financing doesn’t work, as the 2008 presidential election showed; banning anything that could be construed as a campaign contribution ends up inevitably giving the FEC the power to burn books;7 bills to directly prevent Congressmen from raising money just lead to Congressmen finding other ways to raise money (legally), just slightly more covertly; and so on.

Trying to address money in politics at this stage is much too late in the game. Instead of trying to devise ingenious ways to keep Congressmen from rabidly chasing after the money they so desperately need, wouldn’t it be easier if Congressmen didn’t need so much money in the first place?

The Founders’ View

The presiding officer of the Constitutional Convention was George Washington. Washington, by this point a universally respected general and statesman, considered himself a modern Cincinnatus. (If you don’t know the story of Cincinnatus, it’s not very important to this article, but I’ll put it in this footnote:8)

As a result, George Washington allowed the country he had birthed to run itself. He was so respected that everything he said would instantly be made law… so he didn’t say anything. At the Constitutional Convention, General Washington presided, but he did not participate.

Except once.

On the very last day of the convention, General Washington spoke gently but firmly in support of a motion to expand the House of Representatives. The convention minutes describe the scene:

When the President rose, for the purpose of putting the question, he said that although his situation had hitherto restrained him from offering his sentiments on questions depending in the House, and it might be thought, ought now to impose silence on him, yet he could not forbear expressing his wish that the alteration proposed might take place. It was much to be desired that the objections to the plan recommended might be made as few as possible. The smallness of the proportion of Representatives had been considered by many members of the Convention, an insufficient security for the rights & interests of the people. He acknowledged that it had always appeared to himself among the exceptionable parts of the plan; and late as the present moment was for admitting amendments, he thought this of so much consequence that it would give much satisfaction to see it adopted.

The proposal Washington supported would have required that there be one representative for every thirty thousand inhabitants.9 The original text, which Washington opposed because it was “an insufficient security for the rights & interests of the people,” required one representative for every forty thousand inhabitants.

A reminder: today, there is one representative for every seven hundred sixty-one thousand inhabitants. This is more than twenty-five times the threshold Washington apparently considered “safe” for national democracy. Washington thought a Congressional district that is smaller than my current state legislative district was too big for a truly representative national government.

Washington had spoken. The Constitutional Convention approved his correction unanimously. This text is enshrined today in Article I, Section 2: “The number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty thousand…”

A couple years later, in response to Anti-Federalist criticisms of the Constitution, the first Congress proposed a set of constitutional amendments. These amendments came to be known as the Bill of Rights. However, the First Amendment proposed in the Bill of Rights did not protect free speech, freedom of religion, and all the rest.10 The original First Amendment protected the right of the People to be represented in Congress by somebody from their community:

After the first enumeration required by the first article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall be not less than one hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every forty thousand persons, until the number of Representatives shall amount to two hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall not be less than two hundred Representatives, nor more than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons.

The Congressional Apportionment Amendment (or “Article the First,” as it is sometimes known today) would not solve our apportionment problem if ratified today. (Due to hasty last-minute changes, it only makes a meaningful difference while the population is under 8 million, and doesn’t work at all if the population is over 8 million but under 10 million.) But it was ratified by 12 states and came within a hair of adoption multiple times anyway, which does give us an insight into how concerned early Americans were with having a House that was “close to the people.”

No one really disagreed that it was important to have the House grow with the People. Even Federalists who considered the Constitution adequate without a Congressional Apportionment Amendment agreed that small districts were essential. As James Madison and Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist No. 55:

Scarce any article, indeed, in the whole Constitution seems to be rendered more worthy of attention, by the weight of character and the apparent force of argument with which it has been assailed. The charges exhibited against it are, first, that so small a number of representatives will be an unsafe depositary of the public interests; secondly, that they will not possess a proper knowledge of the local circumstances of their numerous constituents; thirdly, that they will be taken from that class of citizens which will sympathize least with the feelings of the mass of the people, and be most likely to aim at a permanent elevation of the few on the depression of the many; fourthly, that defective as the number will be in the first instance, it will be more and more disproportionate, by the increase of the people, and the obstacles which will prevent a correspondent increase of the representatives.

They allowed that these were serious objections; they simply insisted that a ratio of 30,000 persons to one Congressman was adequate. They further insisted that, as the U.S. population grew, so too would Congress responsibly grow the size of the House, even without a constitutional requirement to do so. They didn’t want to constitutionalize it because they didn’t want to fix a particular population ratio, when a higher ratio might be appropriate for a larger country… but, even so, Federalist No. 58 is nothing more than an extended argument that, obviously, the decennial census was designed to create political pressure to expand the House enough to be truly representative, and—obviously!—this pressure would be strong enough to overwhelm all opposition.

Hamilton and Madison were wrong.11

What Actually Happened

The population ratio contemplated by the Congressional Apportionment Amendment was 30,000 people to 1 Congressman as long as there were fewer than 100 total Congressmen, then 40,000 people to a Congressman if there were between 100 and 200 total Congressmen, then 50,000 people to a Congressman for 200 to 300 seats, and so on, with The Ratio growing by ten thousand persons for every hundred Congressmen.

For a while, Congress did indeed expand the House after each census—not by a ton, but enough to stick to The Ratio. However, the wall was breached in 1842, when Congress needed to expand the House from 240 to 300 seats, but instead shrank the House to 223 seats. This put the actual ratio at 72,083 persons to one Congressman. The Whigs in charge argued that this was because the House (at only 240 seats!) was becoming “a mob government” suffering from an “excess of democracy.” (Opponents accused them of shrinking Congress to protect Whig power.)

Look, I am very sympathetic to arguments against “an excess of democracy.” But not in the House. The House is supposed to be “an excess of democracy!” In a system designed to fuse the best of the democratic, oligarchic, and monarchical impulses, it’s really important to have a powerful, uncompromised democratic element in the brew. and that’s why the Founders created it! The purpose of every other part of the national government in our Constitution is to keep the democratic froth the House inevitably produces from spilling over and poisoning the rest of the system—so let the House be democratic!

At any rate, after the 1842 lurch against democracy, the Ratio never recovered. Subsequent Apportionment Acts went back to growing the House every ten years, but they were much stingier about that growth than pre-1842 apportionments. The House had doubled in size between 1789 and 1811 (about 20 years). The original size had been doubled again by 1832 (another 20 years). But, after 1842, the House never doubled again (180 years and counting). The actual ratio was over 100,000 persons per Congressman by 1862 and over 200,000 persons per Congressman by 1911.

Then, calamity: in the 1920 Census, a large shift of rural populations to urban areas threatened to dissolve the seats of a whole lot of Congressmen. So they refused to pass a reapportionment bill—any bill. The House was not updated at all to account for large population shifts between states, and the political pressure that Hamilton and Madison had counted on simply didn’t make a lickspittle’s difference. Only President Herbert Hoover’s demand that they settle the dispute—after eight years of stonewalling—allowed Congress to finally pass a bill: the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929. This bill set an automatic formula for assigning House seats to each state following each census… but it also froze the House at its then-current size of 435 seats, forever.

A century later, America’s population has tripled again, but the House remains at 435 seats. Your Congressman represents, not thirty thousand, not forty thousand, but around seven hundred sixty thousand souls. As a result, you’ve never met your Congressman, and your Congressman spends 30 hours a week in a fundraising cubicle desperately begging special interests for money so he can advertise to you instead. Voter approval of Congress is in the muck. The gap between what the People want what the House actually votes to do is larger than it seemingly ought to be. This seems directly related to district size: there is evidence that the more constituents a representative has, the lower the effectiveness (and approval rating) of that representative.

Yet Congress shows no sign of fixing the problem, soon or ever. That’s where constitutional amendments come in handy.12 That’s why we’re here.

Inadequate Responses

Many observers besides me have noticed that the House is too small, and they have proposed to expand it… a little.

In most states, there are between 700,000 and 800,000 people in each district. (It’s not exactly the same because the U.S. population is not evenly distributed between states, nor perfectly divisible by 435.) But, in Wyoming, there are only 577,000 people per district… because there are only that many people in the entire state of Wyoming. The so-called “Wyoming Rule” says that we should set The Ratio at the population of the smallest state (whatever that happens to be), expanding the House to match. This would ensure that that, at the very least, voters in different states have pretty close to equal representation in the House. If the Wyoming Rule were adopted, we would add 139 seats today, for a total House size of 574. However, we would not necessarily add more seats in the future. If smaller states grew faster than larger states, we’d actually remove seats. District size, in general, would certainly continue to rise.

The Commission on the Practice of Democratic Citizenship recommends that we expand the House by 150 seats (to 585 total), and then continue stingy expansion after future censuses. This would “make up” for all the House seats that have been eliminated by population shifts over the past century. This is self-consciously an attempt to return to the common practice between 1842 and 1929: during this period, the House was usually expanded juuust enough to prevent anyone in Congress from losing their seat.

The gurus at FiveThirtyEight13 think this can be solved with the power of social science, because they always do. Political scientists have observed that many democracies follow a “cube root law”: the size of the lower house in the legislature tends to hover around the cube root of the population size. Political scientists suggest that, because this is the decision many advanced democracies have made, seemingly spontaneously, across a wide range of regions and history, it is probably a naturally good balance between legislators communicating with constituents versus communicating with each other. If the U.S. House followed the cube root law, we would need a total of 693 House seats (adding 258 over today’s total), with a ratio of 478,000 people per Congressman, but this ratio would continue to grow over time.

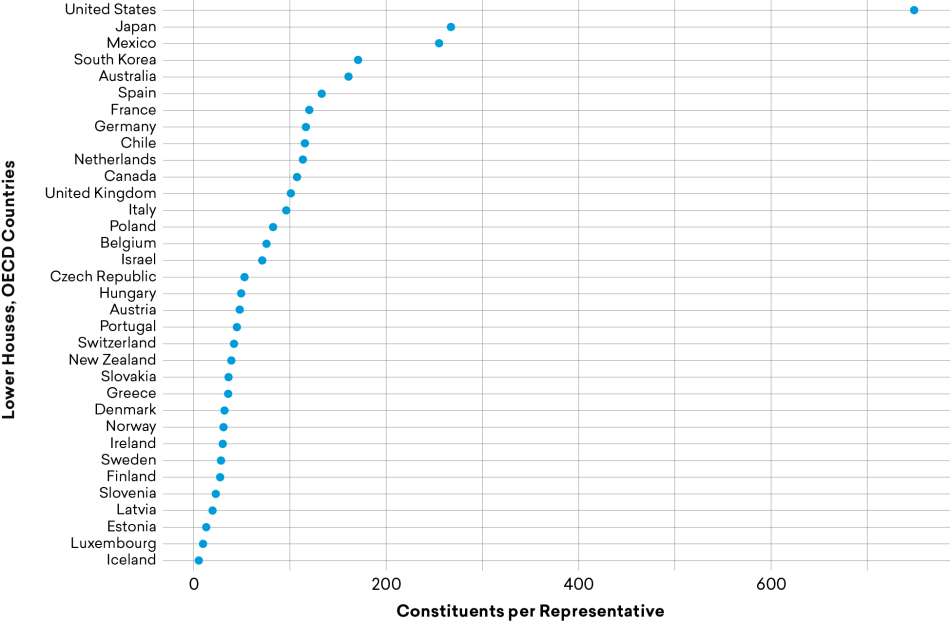

Some people have argued that the United States House is dramatically less representative than any other nation in the OECD.14 That’s true:

If we simply expanded the House until it was as representative as the least representative of the OECD countries, Japan, then we would set our ratio at 265,000 people per Congressman. That would yield a House with about 1,250 seats.

If we extended the original Congressional Apportionment Amendment’s formula (a Ratio growing by 10,000 persons per Congressman for every 100 House seats) all the way out to today, then we would have 1,750 seats in Congress today, with each Congressman representing around 190,000 people.

All of these solutions address some part of the problem, whether it’s inequality between districts or the way the electoral college (which is based on House apportionments) currently distorts the popular will. None of these solutions, however, addresses the root of the problem: whether you live in a district of 762,000 people (current law), 577,000 (Wyoming Rule), or 190,000 (Congressional Apportionment Amendment), you’ll still never meet your Congressman! Indeed, many of these proposals are so modest as to be meaningless. Some (like the Cube Root Law) would even make the ratio worse over the long run.

Put On Your Big Boy Pants and Expand the House

This brings us, finally, back to the constitutional amendment I am proposing in this installation of Some Constitutional Amendments:

AMENDMENT XXXI

There shall not be less than one Representative for every thirty thousand persons, and not more than one Representative for every twenty-five thousand persons.

This amendment sets The Ratio at 30,000 persons per Congressman, as George Washington demanded.

It also tweaks Article I, Section 2 so that the minimum and maximum Ratio are not exactly identical. If every district had to have exactly 30,000 persons, not 29,999 or 30,001, we would have problems, because the U.S. population is not that easily divisible, so this amendment gives Congress a little wiggle room to set the actual ratio between 25,000 and 30,000 persons.

If adopted, this proposed amendment would set the size of the House today at approximately 11,000 seats. Cue panic.

The most common refutation of the “11,000 seats” proposal is a simple blank stare. Faced with proposals to expand the House to a piddling 950 or 1,014 seats, the Commission on the Practice of Democratic Citizenship writes, incredulously, “Arguments against these proposals are fairly simple: each would be too dramatic of an expansion to be feasible.” My proposed expansion, which is twenty times more “dramatic,” is not even on their radar. Alas, as David Lewis said, “I do not know how to refute an incredulous stare.”

You would not believe how often someone replies to the “11,000 seats” proposal with, “But how would you fit 11,000 desks into the House Chamber?” Simple: you wouldn’t! You’d build a new House Chamber!15 The use of the current U.S. Capitol Building and its facilities is not written into the Constitution. The building was constructed to serve the Constitution, not the other way ‘round!

During construction of the new, larger House Chamber, Congress can meet in Capitol One Arena, located in the Federal District, a few blocks from the current Capitol Building, capacity 20,000. After all, during construction of the current U.S. Capitol, the House spent six years meeting in a squat temporary building called “The Oven,” which was connected to the rest of the Capitol by a low wooden gangway. The hockey rink’s a step up. It has air conditioning.16

Many other questions are along similar logistical lines: how would voting work? Would they use clickers? What if the clickers break? How could C-SPAN get the cameras in? Wouldn’t a large House end up more under the sway of leadership than ever? It’s like nobody’s ever seen a parliament of a few thousand people!

In fact, we know how to run a legislative body consisting of several thousand people, because Americans do just that all the time. I’ve even participated in one!

The 2014 Minnesota Republican Party state convention had 2,020 voting delegates at its opening. I was an alternate, but ended up serving as a voting delegate. It was a pretty thrilling day! The GOP senate endorsement was closely fought, and we went to ten ballots over two days. (I had to drop out after the first night.) We followed Robert’s Rules of Order, which work just fine for huge crowds, with standard convention rules. We cast paper ballots and handed them to trusted ballot-counting teams. The House floor “debates” you see on C-SPAN are mostly on-camera onanism to an audience of six or seven people, but, at the MNGOP convention, we fiercely debated the merits of each candidate among ourselves—not so much on mic, but person to person. The candidates courted us. Their surrogates courted us. Candidate teams were back in their offices just off-site, printing up supportive flyers and (as the losing candidates grew desperate) nasty slanders for rapid distribution on the floor.

It was a blast. In the end, the body reached a collective decision. Our candidate was not my first choice, but he was far from my last. Similar conventions happen everywhere in the country, year in and year out, for both parties, without major drama or disaster. The House can run just as smoothly! This is what a republic looks like!

In the House today, the vast majority of the work doesn’t even take place in floor deliberations, anyway. The real work is done in committee chambers and drafting rooms, late-night text chains and face-to-face meetings. Individual members voluntarily band together in “caucuses” to exercise collective power. None of that changes with 11,000 people on the job. What you get instead is more popular representatives overseeing the bureaucracy (especially executive abuses), more Congressmen actually reading the legislation placed before them, more people getting assigned to committees where they actually know what they’re talking about. (Call me crazy, but maybe we should have a few artists on the intellectual property committee and people who don’t call the Internet a “series of tubes” on the Internet committee? 11,000 representatives gives you a very broad range of applicants!)

Indeed, since, today, being a Congressman is only a part-time job—the full-time job is fundraising—a huge amount of the actual work today has to be done by unelected staffers while the Representatives are off in the telemarketing cubicles. In fact, the U.S. House of Representatives currently employs 9,034 staffers, whose median pay falls between $50,000 and $175,000. The average Congressman has 29 staffers.

I’m sure those staffers are all working very hard. But remember my mayor? He gets by with a single clerk. Whom he shares. With the entire city council. Plus the city manager. And the city staff. (She’s great.)

If we expanded the House to 11,000 members, we would not need twenty-five times as much House staff. We would actually need far less House staff. The people we elected to do the work could actually do the work. So next time somebody tells ya, “The last thing Washington needs is more politicians!” remind them that Washington already has “all these politicians.” They just aren’t elected.

Even so, some people, confronted by the “11,000 seats” plan, simply can’t wrap their heads around it. It hits all the checkboxes for my series on constitutional amendments: it’s a “mechanical” tweak that doesn’t take any substantive policy position, it wouldn’t advantage either political party, nobody’s polarized over the issue, and it would fix a part of the original constitutional design that very clearly broke down over a hundred years ago. Yet 11,000 Congressmen is just too weird. Gelding the veto is one thing, but building a new building for the House of Representatives, where practically nobody will get to yell on C-SPAN? Do we even have the budget for comfy desks for everyone?

But, guys, we must never forget that it is a Constitution we are amending. The Constitution is a fundamental document. It seems to me that Congress is fundamentally broken. To restore its function in the constitutional order, I think its character needs to be fundamentally transformed.

Now, it is true that mass meetings with thousands of participants don’t do a great job at absolutely everything. Sometimes, a huge, passionate, populist parliament gets better results. Sometimes, a small, deliberative, detached parliament gets better results. That’s why we have two parliaments: the populist House and the detached Senate.

Except we don’t. The House today is not populist, and the Senate is not detached. They work pretty much the same way, muddle to pretty much the same results, and fail in all the same places. To restore our system and increase the creative tension between House and Senate, we need to heighten the contrast, an issue I’ve touched on before. This proposal does that, very thoroughly, for the House. (Stay tuned for my next proposal, on the Senate.)

Adopting this amendment won’t usher in utopia. No constitutional amendment can do that. Lawmaking will always be messy and frustrating. Yet we have good reason to expect a much larger Congress to be a much better Congress, one that is closer to the people (if still not perfectly representative of them), less dependent on baleful fundraising and special interests (if still not totally free of their influence), more accountable (because less reliant on permanent staff), much more diverse (if that’s what you’re into), and a good bit more human. Yes, they’ll have all the absurdity and drama that humans bring with them—just wait ‘til you see the nuts our crazier districts elect—but they’ll also bring Washington more of a soul.

Ancillary Benefits

Expanding the House to 11,000 people has a couple of handy side benefits, which I mention only in passing.

First, a large House fixes certain disparities in the electoral college.

Each state’s electoral vote equals (the number of Congressmen + the number of Senators) from that state. As a result, Wyoming’s 577,000 residents control 3 electoral votes, or 1 electoral vote for every 192,000 residents. Meanwhile, Ohio’s 11.8 million persons control 18 electoral votes, or 1 for every 655,000 residents. In other words, today, your vote for President has 3.4 times as much impact in Wyoming as it has in Ohio. This is in part because of the districts are too large for small states, and in part because every state gets two electoral votes from senators, which effectively doubles your power if you’re a small state with only one or two representatives in the House.

Under the “11,000 seats” plan, Wyoming would have 21 electoral votes (19 from its House delegation plus two senators), or 1 electoral vote for every 27,500 residents. Ohio would have 395 electoral votes (393 for the House plus two for the Senate), or 1 electoral vote for every 30,000 residents. Wyoming votes for president would still count more as Ohio votes for president, but only 9% more, not 240% more like under the current system. This isn’t a big deal for me, because I don’t think Americans should vote for president in the first place, but, if we’re going to have the current messy electoral college, we may as well make it fair, right?

Second, “11,000 seats” enables some interesting possible experiments in proportional representation, which some states may wish to examine. In the last installment of Some Constitutional Amendments, the anti-gerrymandering amendment, we made some provisions allowing states to use proportional representation, where a party’s share of Congressional seats is made to match up with the party’s share of the overall vote. (For details, read that article.) However, even with the anti-gerrymandering amendment, these experiments would still be very hard to carry out today, because there simply aren’t enough House seats in many states to implement proportional representation.

Having more seats to work with—in many states, hundreds more seats—gives states enough running room to implement some of these alternative voting systems. Of course, in my view, if they go down this road, they should be very careful about how. If they did something like establish multi-member districts where each district elects 15 Congressmen, those districts would each have 450,000 people in them, which would defeat the purpose of expanding the House in the first place! Fortunately, many proportional representation schemes can be implemented without significantly increasing the size of any given electoral district beyond 30,000.

Meanwhile, some people claim that expanding the House is dangerous, because it gives gerrymandering even more power to engineer a majority from a minority of the votes. Perhaps these critics are right, but I think that should be dealt with separately—and conclusively—in another amendment… and, I have proposed an anti-gerrymandering amendment that I think addresses the concern nicely.

Compromises Worth Having

These are just bonuses, though. The core of this proposal is that an 11,000-member House would better serve the purpose for which the House was designed. It would bring Congressmen closer to their constituents and reduce their reliance on special interest donors, while displacing the elite “Congressional staffer” class of lawmakers in favor of actual elected officials. It would make for a very different House of Representatives than we have today, but nobody likes the House we have today anyway, so huzzah.

There’s a healthy possibility that, when they eventually hold an Article V Convention of the States to consider amendments like the ones I’ve proposed in this series, there will be several competing proposals to expand the House. My proposal is the best proposal, the one tied most closely to the intent of the Founders and the will of the People. However, it may become clear that my proposal doesn’t have enough support to pass. In that case, supporters of an expanded House may need to settle for second best.

As a rule of thumb, I think any proposal that adds fewer than 600 seats (for a total of at least 1,035 seats) is not going to have enough of an impact on district size to be worth the effort. Any proposal that rules out future, larger reform should be resisted vigorously, as should any proposal (like the Wyoming Rule or Cube Root Rule) that promises to expand the House today only to constrict its growth (or even shrink the House) later on.

On the other hand, there are groups out there that believe the same things I propose in this article… except, following the original text of the Congressional Apportionment Amendment, they think the Ratio should be 50,000 people to 1 Congressman, not 30,000:1 as this blog proposes. (Their proposal creates 6,500 seats or so, rather than 11,000.) These groups, though not quite ambitious enough for my tastes, should be allies. We can full-throatedly support expansion to 6,500 seats, even if it does not quite complete the work.

If we’re lucky and smart, at the end of all this, you should have a Congressman who’s as accessible as your city council representative or your small-town mayor.

Or, maybe, with 11,000 seats available for the taking, you will be the next Congressman from your newly shrunken district! That’s government of the people, by the people, and for the people: not a House where only career politicians and celebrities have the faintest prayer of winning fantastically expensive elections, but a House where a hugely diverse mosaic of ordinary citizens are the ordinary policymakers proposing the laws that will govern our great nation.

UPDATE 20 June 2023: In the comments, the question was raised, “How much money would this cost?” That’s a reasonable question and I now wish I’d addressed it in the main body of the article. The bottom-line answer is: not very much.

The current cost of the House of Representatives, according to the Congressional Research Service, is $1.489 billion (as of Fiscal Year 2021, the latest year for which I could find figures). Of that total, $0.076 billion goes to pay the actual salaries of the actual members ($174,000/year for 435 members), and I guesstimate that the total cost of salary + benefits for members is $0.151 billion. The majority of the remaining House of Representatives budget goes to their thousands and thousands of staffers.

Meanwhile, the Senate costs $0.998 billion. The Architect of the Capitol Office, which manages the facilities for both houses, costs $0.675 billion. Various Congressional services that support both houses, such as the Congressional Research Service, Congressional Budget Office, Library of Congress, and so on, cost $2.142 billion.

This may sound like a lot of money to you, but, in the context of a U.S. federal budget that spends $4407 billion in a normal year (and which spent $6818 billion in FY2021, due to the pandemic), funding for the entire legislative branch is no more than rounding error. The total annual budget of the House of Representatives—$1.489 billion—is less than we spend every day on Medicare before lunchtime!

Drastic expansion of the U.S. House to 11,000 seats would have a meaningful budgetary impact. Assuming member salaries and benefits remained exactly the same, the total annual cost of Congressional compensation would balloon from $0.151 billion to $3.828 billion. This would be an annual cost.

Meanwhile, we would need to construct a new facility for Congress. To avoid rebuilding every few decades, we would want that facility to have a capacity of 20,000 or 30,000, not just 11,000. Geodis Park, a soccer stadium recently constructed in Nashville, has a capacity of 30,000 people and opened last year. After cost overruns, it ended up costing about $0.345 billion. This is Washington, D.C., and Congressmen won’t need a grass field but probably will need a desk, so triple that to a nice round one-time cost of $1 billion. Ongoing maintenance would undoubtedly require additional annual spending by the Architect of Congress as well; call that (plucks a number out of the air) a 50% increase in the Architect’s budget, so $0.3 billion, annually.

So the ongoing cost of this proposal is $3.9 billion in new annual expenses (salary + benefits + maintenance) and a one-time cost that’s in the ballpark of $1 billion for… well, a new, ballpark-sized House Chamber. These figures assume no other attempt at cost savings.

Substantial cost savings are available. The “Member’s Representational Allowance,” aka the slush fund divvied up between Congressional offices for hiring personal staff, fielding constituent questions, paying for postage, changing the drapes, etc., costs $0.640 billion annually. With 11,000 Congressmen representing the same 331 million Americans (and no longer working out of posh, multiroom, individual Capitol office suites), the MRA certainly does not need to rise, and can almost certainly fall by a very large margin. Meanwhile, most of the House’s remaining budget is currently spent on other staff. (Remember, Congress has a total of about 9,000 staffers.) If 10,500 new Congressmen are now doing the work of Congress’s current 9,000 staffers, many of those staff positions are no longer necessary. Hundreds of millions of dollars can be cut to make budgetary space for the new Congress.

But even if there’s no cost savings, it’s worthwhile. $3.9 billion is a fat stack of cheddar, but it is also less than one-tenth of one percent of overall federal spending—that is, still a rounding error. It’s less than the federal government spends every year subsidizing Amtrak ($4 billion). As for the one-time cost of a new facility, yes, $1 billion is a lot of money to you and me, but Congress recently spent considerably more than that on a one-time “tree equity” planting project.17

I wouldn’t stand by my proposal for an 11,000-member House if it cost $100 billion annually, because we can’t afford that kind of money. If it cost even $20 billion annually, I think people would have reasonable reservations about it, and I would have an uphill battle to persuade you it’s worth it. But a well-functioning Congress is the foundation on which the rest of our system—including all our spending—is based. It’s worth $3.9 billion to have a right-sized Congress, and it could save us far more money in the long run.

tags: #SomeConstitutionalAmendments

To be fair, I think I’ve only ever actually tested this once, but I’ve heard from others that our mayor does, generally, talk back.

For larger cities, the appropriate comparison is probably to your city council member, rather than the mayor. In Chicago, for example, 2.75 million residents are represented by 50 aldermen, which works out to a bit more than 50,000 residents per alderman.

To be fair, I’m aware of very little evidence in general about what works in 1,000-person elections. Possibly it’s not a question Political Science has probed that deeply, or, very possibly, I’m just not great at finding it.

The “30,000 friends-of-friends” figure comes from a Pew Research report from 2012 called “Why most Facebook users get more than they give,” page 21. That’s a decade old, but still seems roughly correct to me.

At the time, the average Facebook user in Pew’s sample had 245 friends, and their average friend had 359 friends (because of the Friendship Paradox). The median Facebook user had 111 friends and their average friend had 265 friends. I’m sure those figures have changed significantly. In fact, Pew found just two years later (“What People Like and Dislike About Facebook”) that the average Facebook user now had 338 friends (not 245) and the median user had 200 (not 111). However, I can’t find more recent figures, and my sense from Facebook is that they haven’t changed that drastically, so the median Facebook user probably still has more than 15,000 but fewer than 90,000 friends-of-friends.

If you are skeptical that Facebook friends should really count as friends, that’s fair. You can naively estimate the number of friends-of-friends you have by yourself at home. The equation is F*((M-1)*(1-C)) = reach, where F is how many friends you have, M is the number of friends your average friend has (remember, this will usually be larger than F), and C is a clustering coefficient. The clustering coefficient is necessary because some of your friends’ friends will already be your friend, or a friend of one of your already-counted friends, and you don’t want to double count them.

In Pew’s Facebook sample, the clustering coefficient was 0.12. (It’s been a very long time since my graph theory course in undergrad computer science, so I hope I’m not explaining that wrong.) ChatGPT told me that a good blind guess for a clustering coefficient in a social graph is between 0.1 and 0.15, and several websites used figures consistent with that, but it varies a lot from person to person, it’s naturally smaller if you have a smaller social graph, and I didn’t dig into this as much as I would have liked. (I had to stop eventually, because this is just a footnote and the article needs writing!)

So if we assume—more consistent with Robin Dunbar’s guesstimates—that the median person has only 40 actual real-world friends (not 111) and that their average friend has 50 real-world friends (not 265), with a lower clustering coefficient of 0.1, then the median person has 40*(49*(0.9)) = 1,764 effective friends-of-friends.

Just as Minnesota state House districts have about twice as many people as my small town, they also usually have about twice as many voters. My town has 10k voters; a Minnesota House election generally draws around 20k. However, Isa Maria Perez-Hedges’s election was pretty lopsided, and only drew 15,000 voters to the polls, about 1.5 times as many voters as my small town.

To be sure, there’s an alternative for candidates who don’t want to spend a lot of money: coast on party identification. There is fairly strong evidence that, in partisan elections, many votes are locked in by the simple presence of “R” or “D” after your name on the ballot. In many places, it’s enough votes to guarantee you win, and you don’t have to lift a finger.

Of course, this makes you dependent on that letter, and beholden to the party bosses. After all, if they take that letter away from you, or you raise your profile enough to attract any kind of controversy among “the base,” you have no defenses, no independent base of support, and the party will destroy you. There are many factors in our national polarization, most of them much larger than “size of congressional district,” but I do think there’s a relationship between modern polarization and congressional candidates’ growing difficulty with connecting directly to their constituents.

That is why the oft-maligned Citizens United case was both correct as a matter of First Amendment law and good as a matter of public policy. “Campaign finance reform” sounds so good, but it just means “the federal government can selectively ban political books by the opposition.”

Cincinnatus was a capable Roman patrician who retired to work his small farm in the country. When Rome was attacked, the Senate demanded that Cincinnatus take on virtually absolute emergency powers for a term of six months in order to rally Rome and defeat the threat. The Latin name for this office was dictator.

At the time, “dictator” did not have the same negative connotations that it has today, but, nevertheless, Romans were keenly aware of how dangerous appointing a dictator could be. Dictatores had a bad tendency (especially later on) of refusing to give up their powers at the end of their six-month term. Sometimes, they’d defeat the invading army only to turn around and sack Rome themselves.

Not so Cincinnatus! Answering the summons of the Senate, he left his farm, took command of Rome, swiftly defeated the enemy, immediately laid down all his emergency powers, and was back at his plough just sixteen days after he left. For centuries, Cincinnatus lived in the imaginations of schoolboys as a heroic model of civic virtue: here was a man who had been given a delicious taste of unthinkable power, but who managed to resist the temptation and focus on saving the country he so dearly loved.

Today, the person who holds that place in the American imagination is George Washington. That’s not an accident. Washington truly admired Cincinnatus, and he and his millions of admirers carefully cultivated that image. That’s how the principal city of Ohio came to be called “Cincinnati,” in honor of General Washington and the Revolutionary War citizen-soldiers.

Technically, the text said that the number of representatives “shall not exceed thirty thousand,” implying that you could have far fewer representatives per person (as we indeed have today)… but the general presumption at the time seems to have been that, quite naturally, Congress would have as many representatives as possible, with the smallest possible population per district, that the Constitution would permit. The actual Congress, once it was created, deviated from this presumption only a little: in the Apportionment Act of 1792, Congress prescribed one representative for every 33,000 persons, slightly higher than the minimum but still well under the 40,000 President Washington had objected to.

What you today know as the First Amendment was originally proposed as the Third Amendment, the right to bear arms was guaranteed by the Fourth Amendment, and so on. The original Second Amendment restricted Congress’s ability to give itself pay increases, and was eventually ratified as the Twenty-Seventh Amendment.

Madison later relented. In fact, Madison was the principal author of the Congressional Apportionment Amendment. If his early version had been adopted, the House would be constitutionally barred from having more than 50,000 constituents per district.

Of course, if Congress will never act to expand the House, this amendment can only be proposed by an Article V Convention of the States. I think, after 250 years, we are due for one of those. However, for a convention to succeed, it has to be an earnest attempt by all sides to try and fix the structure of the Constitution, not an attempt to force through, like, a balanced-budget amendment. Many people forget that the amendments proposed by a Convention of the States still have to be ratified by three-quarters of the states afterward.

I often complained, in recent years, about the very mixed quality of 538’s coverage. Sometimes it’s invaluable, other times it’s Vox Lite, and it’s hard to know when you start an article which one you’re getting.

To be fair, India is worse than we are by a wide margin. Each of their 543 representatives has about 2.5 million constituents, a mind-numbing number. They are not on this chart because India is not in the OECD.

The current House Chamber actually does have a ton of room to expand. You can comfortably get it to 1,725 members without major reconstruction. But that’s not nearly enough for 11,000.

There is also no requirement that Congress meet in Washington, D.C.. The First Congress convened in New York City in 1789, then moved to Philadelphia for a decade. A brief national walkabout could do the Congresscritters some good.

This was part of the Build Back Better Act. It was originally $3 billion with an explicit reference to “tree equity” (which PolitiFact, swamp creature that it is, duly defended) but, after it became a Republican talking point, Democrats wisely cut the appropriation to $1.5 billion and removed the “equity” language. It appears in Sec. 23003(a)(2) of the enacted bill.

“My proposal is the best proposal” 😂 and 17 footnotes!! I liked #8 the best, all new information for me!

James, while I am sympathetic for your arguments for a greatly upsized House of Representatives, I suspect having a standing legislative body the size of a national political convention has all kinds of side affects we can't imagine now that will ultimately be undesirable. For one thing, even if we greatly reduce their salaries (a good thing anyway), remove their personal staffs and their separate offices, and have that body sit only part-time, a 10,000 seat House would be a huge additional expense over the already expensive House we have today.

And I don't see how this solves the problem of forcing elected pols to fundraise. The Senate would still have that problem. And I can readily see that House members who may not need to fundraise for themselves, would still be "encouraged" to spend time calling donors for the Party. Indeed, in such a huge House, the leadership would have a great deal of power, deciding who has plum committee assignments, and who stays on the back bench.

I will look forward to see what you propose for the Senate, as well as the Electoral College. One thing seems for certain: The Founding Father's attempt to have the Senators and President selected at a remove from the popular vote, has failed, and failed as soon as the telegraph improved communications, if not before. (A little observed fact about the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates is that those two Senate candidates, ostensibly elected by the Illinois legislature, were campaigning directly to the people. Even at that date, the legislatlve elections were proxies for the Senate race).

I also found your link to your alternative history of the 2020 election and its aftermath. I am at once heartened by the institutions that held in the real 2020 election (unlike in your fictional recount) and dismayed by how close we came to the chaos in your account. Mike Pence gets a lot more credit than you gave him in that piece. As do the courts. As does the Pennsylvania electoral system, which had to deal with COVID, as did the rest of the country.