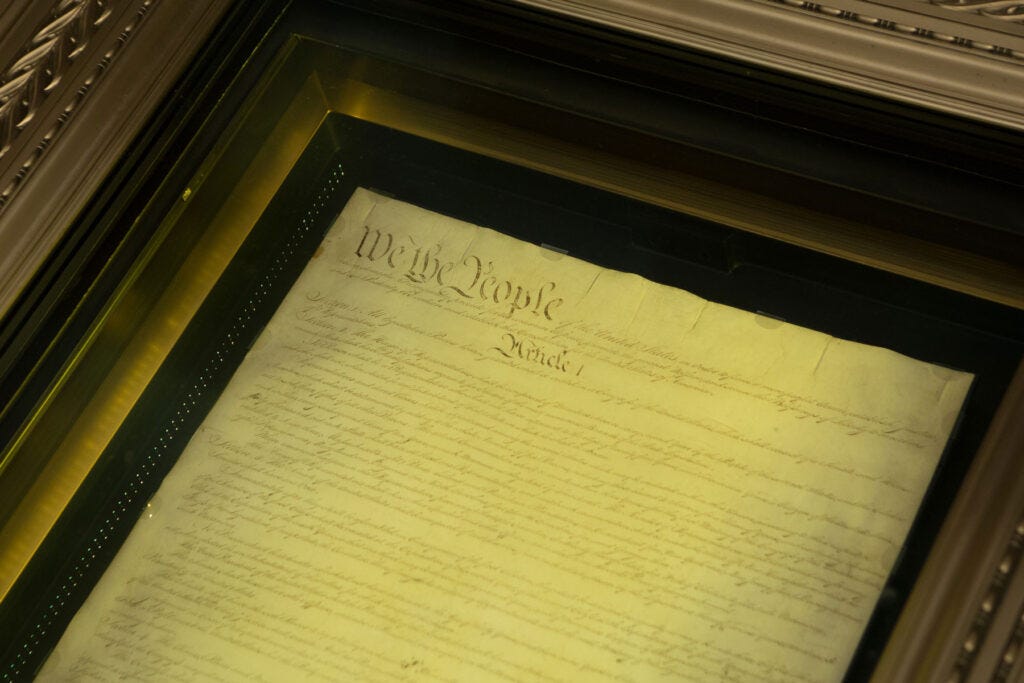

Some Principles for Proposing Constitutional Amendments (On One's Blog)

Let's recklessly start another series! Worthy Reads is going well, but I don't want the blog to be taken over by my clippings from other blogs, so I've been saving up Worthy Reads for months without writing anything else. It's time to fix that. In each entry of this series, I'll propose an amendment to the U.S. Constitution for your consideration.

Except for this entry. Today's entry is an introduction.

If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to control itself.

James Madison

James Madison famously believed that the Constitution required no Bill of Rights, because its fundamental structure was enough to secure the rights of the people. I think history has proved him wrong about that—but not entirely wrong. The structure of our government can, to a tremendous extent, shape its actions towards (or away from) the common good. By many measures, the most generous and popular Bill of Rights in the history of the world was contained in the Constitution of the Soviet Union... but the Soviet Union was structured in such a way that nothing its Bill of Rights said actually mattered or was in any way protected.

The fundamental insight of the U.S. Constitution, of Madison's Constitution, is that the government serves the People best when it has some accountability to them (no dictatorships), but is not subject to the mob's whim (no democracies), and when it forces competing interests to police one another and make compromises rather than allowing any single force or party to control all the levers of power at once (which means no parliament).

Thus Madison and the Founders gave us the best system of government yet devised: an elected republic, where the common people and their popular will were set against the aristocracy and institutional interests (the House vs the Senate); different states against one another (the Senate within itself); different population centers against one another (the House within itself); with the legislative and executive branches all at each other's throats, jealously guarding their own power and prerogatives; as the judiciary refereed by common consent of the political branches. We also have a federal government with limited powers, locked in an eternal tug-of-war with fifty (or more) states, most of whom have broader powers than the federal government, but without the military or economic power to fully exercise it.

Or, at least, that was the idea.

The American government has failed in several key ways. The legal system we have is not the legal system the Founders envisioned. It's not even close:

Congress (Article I) is a bicameral ATM that dispenses money created by the Federal Reserve, a quasi-governmental organization of private banks that everyone agrees must never be the subject of direct government intervention. A lot, and I mean a lot, of laws are passed without being read by the Congresscritters voting for and against them.

This is ultimately relatively unimportant because the President (Article II) is the Head of State and sort of the Head of Government, and has a Cabinet of Ministers with whom he isn't supposed to talk too much for fear of having some influence on their behavior. Those Ministers, whom he appoints with Congressional approval, go on to make the laws described above, and to enforce the laws, and sometimes not, and sometimes run roughshod over the people because they can. This is only the President's fault if he belongs to a party or belief unpopular with the aristocracy, more on this below, and is otherwise beyond his control because he's not supposed to politicize his own Branch and anyway the thing's too big.

Article III (the judiciary) writes amendments to the Constitution, beginning with the one allowing them to write Amendments ex nihilo and on their own, and decides national policy on issues of incredible importance under the guise of resolving cases and controversies. The Judiciary also decides on the relative balance of power of the federal and state governments, the limits of the other branches' power, and whether actions undertaken by the other branches are acceptable enough to stand. Thus, the only unelected branch, other than apparently Article IIA, has the most direct and only unchecked decision on national lawmaking of all.

The President can go to war without Congress agreeing, or make treaties-that-last-as-long-as-his-Presidency without Congress agreeing, or refuse to enforce laws, or create whole new legal programs, and Congress cannot refuse to fund any of it because reasons. Additionally, the President cannot cancel any of the laws his Branch makes, even if directly in violation of the Constitution, unless Article III signs off or Article I signs off (and Article III signs off).

Thomas H. Crown, 2014

(Curtis Yarvin makes a similar point, but even more brutally, in his elucidation of the "ritual Constitution" and the "descriptive Constitution.")

Partly (largely) this is our elected officials' fault. A lot of this stuff happened because Congress wrote and passed bad laws, because they seemed like a good idea at the time, and now the laws are so thick and interdependent that pulling some of the bad laws down would be like pulling out the center brick in a Jenga tower. That's an understandable fear, but inadequate to our predicament. It has allowed the Deep State they constructed to wrest the reins of governance away from them.

(SIDEBAR: People get uncomfortable about "Deep State" talk, because it sounds conspiratorial. This is easily cured. The Deep State is the subject of Yes, Minister and its sequel series Yes, Prime Minister, a popular British sitcom from the 1980s and Margaret Thatcher's favorite program. Whenever you hear the phrase, "the Deep State," replace it in your head with "Sir Humphrey Appleby" until the true nature of the Deep State has been drilled into your head enough that the replacement is no longer necessary.)

Partly this is our fault. We have in some ways betrayed the system we were given, especially in our long careless descent down the roads to democracy and tyranny (they're really the same road). We lack the moral virtue and civic energy that the Founding generation felt was essential to successful republican governance; we belong to a shockingly supine and politically dull-witted century, as did our parents and our grandparents. (Blame radio, TV, and video games, I guess, in that chronological order.) We don't teach civics; when we do teach civics, we teach them badly; and the current effective political control of America's classrooms by a single partisan side (the Left) makes the teaching of political theory fraught anyway.

But also, partly, this is the Constitution's fault. The Constitution has a number of mechanisms that do not function correctly. The government of mutual checks and balances they envisioned, therefore, has more or less dissolved into a mess. Some of these mechanisms never worked and were never going to work. Some of them worked for a while, then stopped working. Some of them were sabotaged in unexpected ways. Many of them failed because the Founders failed to account for the inevitable rise of political parties. Now, I love our Constitution. I love James Madison. I think the American system of government is an all-time great. The Founders were great men... but they were not angels. Geniuses... but not fortune-tellers. It is neither surprising that they failed to foresee every detail of how their incredible document would play out in reality, nor a betrayal to point out the few breakdowns and propose fixes. Hence this series.

I take as my starting point that amending the Bill of Rights to settle important substantive questions like "the national debt" or "abortion" is simultaneously impossible, pointless, and boring. It's impossible because these are deeply divisive issues (that's why people are trying to settle them by amendment), and you need about 85%+ public support to ratify a constitutional amendment. It's pointless because, if you could ever get that much public support for your divisive policy question, you'd no longer need a constitutional amendment, because you'd have won the argument and all the relevant laws already. It's boring because it's just an extension of substantive political debates we already have all day every day. (Boring is not actually a bad thing for government—I'm not here to insult the 20th Amendment—but boring is bad for blogging.) The only time you can actually usefully add to the Bill of Rights is when you've just won a civil war and you can force your vanquished enemy to ratify your views at the point of a gun.

As another starting point, I generally reject constitutional amendments that rely heavily on judicial interpretation to be given effect, or which effectively hand legislative power to the judiciary. Everyone knows that writing, "Racist policies are unconstitutional" into the Constitution wouldn't actually ban "racist policies"; it would merely ban whatever a judge (or entrenched bureaucrat) will label a "racist policy," and we all know that judges (and bureaucrats) are fallible on their best days and downright evil on their worst, because they're human. Everyone knows that handing the essential policy-making power over to them flies in the face of the separation of powers. Whether you're more scared of conservative judges or progressive judges, we're all scared of judges of some stripe or another, and we'd have to be pretty stupid to give them even more power.

Nevertheless, people love doing these two things. The New York Times recently ran a feature where they asked prominent law-and-politics people to propose amendments. All but one of these proposals (including one I really liked, by Xan Desanctis) was either "constitutionalizing a divisive policy argument" or "giving judges free rein to set policy," sometimes both at the same time!

The National Constitution Center did a similar thing, except they let their teams rewrite the whole Constitution. Result? The majority of the work turned in by two of the three teams was this same unrealistic partisan score-settling, with some healthy judge-worship on the side.

Oh, well. Human nature, I guess.

This series will not have any of those. I will not pitch you a conservative Personhood Amendment, nor a progressive narrowing of the First Amendment. We're going to try and be like James Madison, fixing the system in conspicuously non-partisan ways, so that the men (not angels) who run our government are nudged toward wisely and justly governing its subjects without specific directives from us, the Constitution writers, on what that means.

Let's roll! First post tomorrow: "Geld the Veto."

Tag: #SomeConstitutionalAmendments