NOTICE: This post is long, even for me. If you get tired, there are two “break points” marked in the article. If you’re returning from a break, here are links to where you left off:

first break point | second break point

WARNING: This post contains major spoilers for a novel published in 1979.

In William Styron’s novel, Sophie’s Choice, Sophie Zawistowska is a Polish Catholic imprisoned at Auschwitz with her two children, a boy and a girl, both between the ages of five and ten. An S.S. officer takes an interest in Sophie while she awaits processing. Upon learning that she is a believer in Christ, he sneeringly grants her the “privilege” of a choice:

“You may keep one of your children.”

The other will be killed in the gas chamber.

Sophie insists that she cannot choose one of her children to die. The S.S. officer says that, if she refuses to choose, he will gas them both. Sophie continues to refuse. The S.S. man orders soldiers to take both children to the gas chamber. As the soldiers seize the children from her, Sophie bursts out:

Take my little girl!

Her daughter, who is adorable, is undone by this betrayal. The Nazis carry her off to the gas chamber, screaming, as her mother weeps in horror. Little Eva is gassed to death. Sophie has saved her son at the cost of her daughter.

Naturally, this destroys Sophie. After the war, she becomes a high-functioning alcoholic hedonist, abandoning herself in pleasures to numb her self-loathing and despair. She craves punishment for her choice, seeking out and standing by an increasingly abusive (and mentally ill) boyfriend. Finally, she takes cyanide and dies. It is almost impossible to imagine any other outcome. A 1982 film adaptation starring Meryl Streep dramatized the scene:

Since I knew what was coming, I watched it impassively. I only grimaced when they took the girl, and gasped a little at her scream. Then it was over, and I came back to write this post. I worked for almost a minute before the tears came and I had to stop for a little while. My girls are about that age.

Sophie is a victim here. Let’s be clear about that. She acts under the most extreme duress, fully in the power of one of the more demonic societies ever to arise on this demon-haunted Earth. She did not gas her child; she made a choice in order to save one of her children.

Yet that seems to be no comfort at all. It was not just the death of her child that destroyed Sophie. It was her participation in that death. Something about what she did seems deeply morally wrong, at least to me. Sophie herself would be the first to agree with me.

Maybe that’s just Sophie and me, though.1 This election season, almost every single person I know has been telling me that, when faced with two evil outcomes, we should always choose the lesser of two evils, no matter what. In fact, what’s really morally questionable is if we refuse to choose the lesser evil.

I have probed right-wingers, left-wingers, and centrists about this. I have tried to find their limiting principle, the line they wouldn’t cross. “Would there be a moral obligation to vote in an election where Hitler and Stalin are the only choices?” “Okay, how about between Satan and Abaddon?”

“Kang and Kodos?”

Perhaps you, dear reader, are the exception, but, among those I’ve spoken to, I have not found any limiting principle. I have had people tell me directly that, between Hitler and Stalin, they’d choose the lesser evil.2

In other words, almost everyone I know seems to think that Sophie’s choice was not merely excusable, given the brutal circumstances and understandable human weakness. They seem to believe Sophie was actually correct.

No, that’s not quite accurate. We live in an era of high polarization! Probably half the people I know think Sophie was correct. Everyone else I know thinks Sophie should have had her son killed instead.

Cooperation With Evil

You read the title; you know what this article is about. Eventually, we are going to talk about voting, and specifically voting in the 2024 presidential election. However, you and I both probably have strong opinions about 2024. As soon as I start talking about it, everyone’s going to get real defensive, and it’s going to be hard to make any headway… so I am going to avoid mentioning 2024 for as long as I can. We’ll build the foundations first. (Don’t skip this part!3)

So let’s keep talking about Sophie’s moral dilemma.

When I come across a difficult moral problem, I usually go find out what the Catholic Church has said about it. I think that’s a good idea even if you’re not Catholic.

The Catholic Church has been around for two thousand years. It is famously systematic and exacting in its rules. Setting its mind (or changing it) takes centuries.4 It has dealt with every difficult moral problem you have ever thought of, and thousands of others that have never crossed your mind. Its conclusions are the ethical basis of our civilization, and it has therefore played an indirect but major role in forming your own personal moral code. (The Catholic Church is not the only reason your morality differs from pagan morality, but it’s a big one.) Even when the Catholic Church is wrong,5 its top thinkers (who are rather notoriously brilliant) have still probably been thinking and writing about your problem for several lifetimes, which is at least one lifetime longer than you have. What the Church and its thinkers have to say might be right, it might be wrong, but it’s certainly going to give you a better introduction to the discussion than anything you can come up with on your own.

Sure enough, the Church’s theologians have a good deal to say about cooperating with evil. Let’s walk through it.

All too often, we are invited to help other people commit evil acts. Generally speaking, our basic moral duty is to refuse.6 We should not help other people commit evil acts. If we did, we would become responsible for those acts. Duh!

However, there are quite a few degrees of responsibility. Suppose you live in 1850s Pennsylvania. If you support universal abolition, but you buy Southern cotton in your town marketplace anyway, your purchase supports slave-powered cotton plantations and the institution of slavery, so your purchase is a form of cooperation with evil—even if Southern cotton is the only cotton for sale in your city. Likewise, suppose you see a runaway slave running past your log cabin late one night. If you leap from your bed, cry “ain’t no property escaping across my land!”, run outside, apprehend her, hold her at gunpoint, call the slave-catchers, and deliver up the runaway into their cruel hands, you have cooperated with the evil of slavery. However, this second form of cooperation is clearly much worse than the first kind. Why?

Categories of Cooperation

Content warning: this section contains frank analysis of rape.

The Catholic Church divides cooperation with evil into two fundamental types:

Formal cooperation is where you share the intention of the evildoer. You’re at a frat party when an evildoer says, “I’m going to sexually assault that passed-out girl on the couch,” and you say, “Yeah, man, go for it!”

Material cooperation is where you knowingly give the evildoer material aid in accomplishing his goal. The evildoer says, “I’m going to sexually assault that drunk girl on the couch,” and you say, “You don’t want to catch or spread an STD! Here’s a condom.”

Formal cooperation is pretty cut-and-dried. It exists principally in the heart, and begins in your interior consent (even reluctant consent) to the intention of the evildoer. It may be expressed explicitly (“Yeah, man, go for it!”) or implicitly (“As a Catholic, I can’t say I approve, but a man’s gotta get his rocks off somehow”), but both count.

Material cooperation is much more complex. Catholic moral theology describes material cooperation along two different spectra.7

Degrees of Proximity

The first spectrum is proximity. The more closely your cooperation is connected to the evil act, the more serious it is.

At one extreme is immediate material cooperation, also known as participation. This is direct participation in the evil act.

If an evildoer tells you that he’s going to sexually assault a passed-out drunk girl, and you agree to hold her down in case she wakes up and fights back, you are now a participant in the rape. (The common legal term here is accomplice.)

If you participate because the evildoer is your friend and you want him to “have fun,” you are also formally cooperating. However, it is possible to participate in a rape without formal cooperation. Perhaps the evildoer is holding a gun to your head and, despite your protests, he says that he’ll kill you if you don’t hold the girl down. (The moral theology term for this is duress.) You reluctantly agree because you don’t want to die. When the girl wakes up and fights back, you still hold her down, but you don’t want her to be raped. This is still immediate material cooperation, but not formal cooperation.

When you aren’t directly participating in the evil act, but your action is nevertheless closely connected to it, it is more proximate material cooperation.

Suppose the evildoer is your roommate. One day, he tells you that there is a particular girl he wants to drug and rape at a frat party tonight, but there are a lot of frat parties going on tonight. The evildoer doesn’t know which party she’s going to. He asks you, since you have a class with her. You tell the evildoer exactly where his victim is going to be, even though you know that he intends to rape her. That’s not participation, but it’s pretty close, so you are engaged in pretty proximate material cooperation. (In legal terms, you might be an accessory.)

If you tell the evildoer where she’ll be because you hate the girl and you want her to get raped, you are also formally cooperating. However, once again, material cooperation does not require formal cooperation. Maybe you only reluctantly give the evildoer the location because he’s blackmailing you and threatens to ruin your life. Maybe you don’t actually want the girl to get raped, but the evildoer offers you $100,000 for the location and your silence. Maybe the evildoer once saved your life, and you (mistakenly) feel that you owe him this favor, although you make your disapproval clear. In all these cases, you are engaged in pretty proximate material cooperation with the rape, even though you do not intend the rape.8

One more thing worth noting: the evildoer might succeed at the rape, but he might well fail. The doorman at the party might think the evildoer has a shady look and refuse entry. The girl might come down with the flu and stay home. The evildoer might get caught trying to drug her and get kicked out of the premises. However, even if the rape fails, you have still engaged in proximate material cooperation with rape. Morally speaking, you are just as guilty as you would have been had he succeeded.9

When you aren’t directly participating in the evil act, and your action is less closely connected to it, it is more remote material cooperation.

These two terms, proximate and remote, are often used by internet poasters as though they were clear, distinct, categories separated by bright, obvious lines. They are not. These terms are relative. I will give a couple of examples to illustrate.

Suppose that you are a mechanic. A man has his car towed in and asks you to replace his car’s alternator, which has failed. While you are working on it, you overhear him talking to someone on his cell phone:

No, sorry, I’m gonna miss it tonight, but my roommate, you remember him?… Yeah, he’s coming… No, I told him where it is… But he told me straight-up that he wanted to rape that one girl, and I was all… No, man, I think he’s totally serious. He’s got a whole plan worked out. …Yeah, I don’t know, he just wanted me to make sure you had the roofies… Okay, he’ll be glad to hear it. I’m just getting his car fixed for him, then he’ll come straight over.

Oh no! You’re repairing the evildoer’s car!

You now have strong reason to believe that someone intends to use this car to facilitate a specific rape. If you finish repairing the car, then, you are cooperating with evil.

However, compared to the roommate from the last example, you are a step further removed from the rape. You fixing the evildoer’s car is not nearly as close to direct participation in the rape as that guy telling the evildoer exactly where to find her.10 If you continue fixing the car, your action is more remote than the roommate’s action.

Now stop imagining yourself as the mechanic. Suppose that you are a cashier at a hardware store. A mechanic comes in and buys a wrench. At checkout, he says, “Honestly, I was glad my wrench went missing. I need the wrench to finish this job, but what I really needed was an excuse to get out and think for a bit. I think the car I’m fixing is going to be used in a rape tonight!” If you sell the mechanic his wrench, you are cooperating with evil (by giving him a wrench to fix the car to transport the evildoer to commit the rape) but more remotely than the mechanic (who actually fixes the car).

The mechanic’s cooperation, then, is remote when compared to the roommate’s, but the mechanic’s cooperation is proximate compared to the cashier.

This chain of proximity radiates outward from the evil act, growing ever more distant from the rape in terms of time, distance, specific causation, and specific knowledge.

For instance, the landlord who rented the house to the frat ten years ago, despite their somewhat shady reputation, certainly took on the knowing risk of a rape. In a real sense, then, he cooperated with the rape, but his proximity is much more remote than the mechanic’s or even the cashier’s.

The evildoer works at a big-box mart where you, in real-life, have probably shopped, which means your money contributed to the evildoer’s wages, and the evildoer used some of those wages to buy roofies. When you shop at the big-box mart, naturally you know that, statistically, some employees will use their wages for evil. Technically, then, shopping at the big-box mart is also material cooperation with evil… but your relationship to the evil is very remote in terms of time, distance, causation, and knowledge.

Degrees of Necessity

The other way Catholic thinkers evaluate cooperation with evil is in terms of necessity. The more necessary your cooperation is to the accomplishment of the evil act, the more serious it is.

This spectrum is not as richly labeled as the spectrum of proximity.11 There is simply a range from necessary to… well, unnecessary. Hey, jargon isn’t always complicated.

If the evil act certainly could not be carried out without your cooperation, your cooperation is absolutely necessary. If the evil act would certainly happen anyway, your cooperation is absolutely unnecessary. Anything uncertain lives on a spectrum between the two.

For example, if you’re the roommate, and nobody but you knows which party the girl is going to, your cooperation is mostly necessary to the rape. It’s not absolutely necessary because the evildoer might have backup plans: he might randomly choose a party and get lucky, for example. Nevertheless, your telling him which party to go to makes the rape much more likely to happen, so your cooperation is pretty necessary. On the other hand, if you have five other roommates, all of whom know the same information as you, and you think some of them are likely to tell the evildoer anyway, your cooperation is much less necessary.

The necessity of a cooperating act does not inherently have anything to do with the its proximity. Suppose you hold down the victim during the rape. If the victim wakes up and fights back, it is also necessary cooperation. If the victim is drugged so heavily that she never stirs, your cooperation is unnecessary. Either way, though, it’s immediate material cooperation.

We live in an uncertain world, so it is nearly impossible to say with certainty whether a cooperating act was necessary or not until after the fact—and, often, not even then. Our moral responsibility is based on what was reasonably foreseeable at the time we chose to cooperate.

A Moral Analysis

So far, all we have done is describe different distances between an evildoer’s evil act and various possible cooperating acts, without saying anything about whether the cooperating acts are right or wrong. It is hard for me to see anything objectionable—or even anything specifically Catholic!—about this analysis… except insofar as it is very Catholic to be this anal-retentive about categorizing things. I hope it all sounds reasonable to you. Now we turn to the Catholic tradition’s moral conclusions, which are more disputable (though, I think, still quite reasonable).

Formal cooperation, according to the Church, is always unethical. You can never positively intend an evil deed, even reluctantly.12 Joining your will to that of the evildoer makes you fully an accomplice to his evil deed. If you are under duress, your culpability (your personal objective guilt) is lessened, but not erased, and the magnitude of the crime itself remains just as great.

Immediate material cooperation cannot be separated from implicit formal cooperation.13 Therefore, immediate material cooperation is always unethical. You must never directly participate in an evil act, even reluctantly. In other words, it doesn’t matter if the evildoer has a gun to your head and has already killed three people for refusing him. It doesn’t even matter if the evildoer has a gun to your child’s head. If he asks you to hold down the girl while he rapes her, your moral duty is to refuse. Few would blame you very much, under the circumstances, if you broke down and held the girl down to save your own life, but you would deserve some blame. And, in your heart of hearts, you would almost certainly know it.

After all, evil isn’t just wrong because it hurts the world. Evil hurts you, directly. A classic formula is that evil “darkens the intellect” and “binds the will.”14 Think of the worst person you know, and this becomes clear. Each time the will of a good person fails, it becomes more difficult for him to resist similar temptations in the future—binding the will. Meanwhile, his natural sense of right and wrong gradually gutters out under the weight of habit—darkening the intellect.

The evildoer (even a mere cooperating evildoer) rationalizes what he has done. He can’t really help this. Even if he knows he’ll be tempted to rationalize it, the desire to soften the edges of one’s own evil acts is almost irresistible. His whole mind is slowly warped around that rationalization. After all, if you tell an AI to draw “a perfectly ordinary man, with two human arms, two human legs, two human eyes, a human nose, and eight spider arms,” that last, bizarre instruction doesn’t fit, and warps the whole neural net; the entire image has to be restructured around that one broken concept. Evil does not fit the human pattern, and so warps our neural net the same way. Which is a long way of saying: evildoing darkens the intellect.

In addition to this genuine internal damage, there is also the evil inflicted on the world, for which you are responsible. This, too, will come back to hurt you some more, in the form of guilt and shame, whether repressed or not.

Of course, all this damage happens slower and less severely if we do evil only reluctantly, or if we are only cooperating with the evil. The Catholic position, however, is that the damage still happens, because our psychology is shaped by our actions whether we like it or not. Think of proximity to evil as proximity to the One Ring in Tolkien. (Middle-Earth is proudly ruled by Catholic moral theory.) Because Gollum acquired the Ring through murder, it corrupted him much more quickly, deeply, and completely than it did Frodo… but the Ring’s power to corrupt still harmed Frodo beyond measure.

Sophie’s Error

We can now understand where poor Sophie made her (understandable) mistake—the mistake that, in the end, killed both little Eva and Sophie herself.

Sophie never actually had a choice. The S.S. guard gave her the illusion of choice. He held 100% of the power. If Sophie had refused to pick a child, he might very well have followed through on his threat to kill them both. Then again, he might have spared one, or both. Likewise, once Sophie did choose one of her children, he might have killed both anyway, or killed the one Sophie didn’t choose. The power was always, entirely, in his hands.

The only reason the S.S. guard gave Sophie the illusion of choice was to trick Sophie into formal cooperation with the murder of her own daughter.16 In the book, it is especially clear that the guard hates Sophie for her belief in Christ, and wants to strike at her by coaxing her into the greatest blasphemy of all.

The only way you can escape this situation with your soul intact, then, is to refuse the choice. Do not pick a child. Do not trample the fumi-e. Do not play the Hunger Games. What the evildoer chooses to do, after you sit down and refuse to play his game, is his choice alone… as it always truly was.

Yes, because evil darkens the intellect, he will likely see your refusal as a hateful rebuke, a piercing light into the darkness of his cruel will. He will probably make you pay for it. Maybe others, too. But he will do it alone. You will not have killed your child. You will remain you.

My parents (who taught me well) taught me this solution to Sophie’s “Choice” from a young age, and it has always seemed clearly right to me. If it seems wrong to you, perhaps my argument isn’t going to connect with you and you can skip the rest of this article—unless you’re Catholic.17

Still, not every case of cooperation with evil is literally “send one of your babies to the gas chamber.” There must be some room for cooperation, or we’d never be able to buy groceries.

The Case for Cooperation

Material cooperation that is not immediate and not formal might be justifiable, under certain circumstances. Because of the corrupting power of evil, the burden of proof always lies on the cooperator to show that cooperation is justified in a given situation, and the presumption is that you should not cooperate with evil… but there is a case to be made.

Once again, you can never do evil, not even so good may come of it. Nor may you intend evil. However, if you are intending to bring about good, you can sometimes take a neutral or good action while tolerating an evil that you foresee could arise indirectly from your morally neutral action. Indirectness is extremely important here: the good you are seeking cannot depend upon the evil, and it cannot result from the evil.18

Even then, you need a hefty justification even to tolerate the possible evil result:

First, there must be no reasonable way to obtain your intended good without the evil results. If there’s a way to get the good without the bad, obviously, you have to do that.

Second, the good must be proportionate to the evil you might be causing. “Proportionate” means that, if the evil you anticipate is quite small, then even a fairly small intended good can justify cooperation. However, if the evil is very great (like a single rape, or a single child gassed by Nazis), and your contribution to it is significant, then the good you are pursuing must be extraordinarily good—good enough to outweigh that evil.

Making this decision requires the potential cooperator to engage in a very ugly moral calculus. What would outweigh a rape? The hideousness of that question, and your natural instinct to recoil from it, is a good illustration of why Catholic moralists tend to treat cooperation with evil like it were glowing green nuclear waste that can only be handled with eleven-foot iron tongs and full-body protection.

Still, the “weight” of the evil becomes less and less as you move further and further away from the original evil act in both proximity and necessity. Let’s turn back to our examples to see how that works in practice:

The roommate (who told the evildoer which party the girl was going to) is so proximate to the rape, so necessary to its success, that he could only justify helping the evildoer if the evildoer were going to use his knowledge of the party to accomplish some good so great it would actually outweigh the rape (or very nearly so). The roommate’s contribution to the rape is too significant to be balanced out by anything less. However, I have no clear idea what good could plausibly do that, and I don’t care to contrive an example. This cooperation is so proximate, so necessary, so close to immediate cooperation, that it is probably only justifiable in theory and in off-the-wall hypotheticals, not in practice.

However, the cashier at the hardware store is several steps more distant from the rape in distance, time, causation, knowledge, and necessity. He would only contribute a small amount to the eventual rape. Therefore, he might reasonably consider that:

selling a mechanic a wrench is morally neutral,

refusal to sell the mechanic a wrench would violate store policy and could lead to the cashier losing his job,

his refusal is not going to prevent the mechanic from fixing the car (because there are three other hardware stores nearby),

the evildoer might accomplish the rape even without the car, and

the cashier has a family to feed.

Our cashier faces a difficult moral dilemma, with no clear answer. This is a matter of prudential judgment: that is, it can only finally be resolved by the cashier weighing things up internally, in his conscience (which we can only hope is well-formed and practiced in all the virtues), perhaps with the help of trusted moral authorities, and, at last, coming to a decision. The objectively correct answer, in such complex cases, is known only by God, and people can disagree in good conscience about what it is. All things considered, I personally think the cashier ought to at least try to refuse the sale, but it’s a close call and depends greatly on specific, concrete facts that we can’t know in an abstract hypothetical.

Finally, consider a customer of the hardware store. She is very remote from the rape, and her patronage is almost totally unnecessary to the rape. She also lacks any specific knowledge of the rape; she has only that general knowledge that, if you spend money on goods and services, some people who receive the money will use it for evil. By purchasing her next socket wrench at this hardware store, this customer is, technically, cooperating with evil (by paying the store to buy wrenches that it may sell to mechanics who may use the wrenches to fix cars for rapists), but her involvement is so remote and so unnecessary to the evil, her contribution to the eventual rape so tiny and indirect, that probably the only justification she needs is “I need a new socket wrench.” The good of the socket wrench very likely outweighs her (teensy-tiny, unrecognized) contribution to the eventual rape.

The cooperator should not forget, too, that her cooperation won’t just have an effect on the world. It will have an effect on herself. Even if her cooperation is justified under the circumstances, proximity to evil always leaves scars—and those scars get bigger the more proximate and more necessary to the evil. They darken the intellect. They bind the will. As Fr. Dominic Prümmer, O.P. explained in his 1949 Handbook of Moral Theology:

…[The evil effect]—though not intended by the agent—remains a material sin, and frequently engenders a grave risk of formal sin.

I can’t (easily) prove that any of this is correct, because you can’t do proofs of ethical principles without a shared understanding of the human person, which does not exist in a pluralist society. However, this is one of those Catholic teachings that seems so common-sensical to me that I would take it with me if I ever left the Church.19

This article’s kinda long, isn’t it? If you’d like to take a break, here’s a good place to stop for the day. You can come back tomorrow and read on from here. Nobody’ll judge.

Voting Ethically

There is not a tremendous amount of material on Catholic voting ethics, and much of what does exist is sloppy, partisan hackwork designed to get you to vote a certain way.20 Worse, many of the principal documents—the ones that are generally regarded as at least somewhat authoritative—tend to assume that voters are acting in a context of what I am going to call ordinary politics.

In ordinary politics, all candidates agree on the basic vision of the common good. There is complete agreement on the fundamental rights:

life, the single right without which all other rights are “false and illusory,”

liberty to develop one’s human potential,21 and

recognition of the equally infinite dignity of every human.22

There is also broad agreement on what is needed to fully develop our human potential, and agreement that government plays some role in ensuring that everyone has those things: food, clothing, shelter, health, work, religion, education, culture, knowledge, peace, the rule of law, the right to pursue one’s vocation, the right to establish and raise a family,23 and much else besides.24

Of course, we will almost certainly disagree on how best to achieve these goals. We will have arguments, perhaps bitter ones, about which level of government is best suited to deal with an obstacle to human flourishing: federal, state, city, county, private charity, family, individual. We will disagree about levels of taxation, levels of immigration, policing methods, what time school should start in the morning, whether the city should prioritize snow plowing or walkability, and whether the country should go to war against an enemy or try to sue for peace. These disagreements will be deep. Many, many people’s lives and happiness will ride on the outcomes. Nevertheless, this is ordinary politics.

When casting a vote during a time of ordinary politics, citizens should inform themselves about the candidates, listen to respected moral authorities,25 and make a prudential judgment about which candidate is more likely to do the most to advance the common good. Citizens can disagree about that decision without believing that the other side has done something evil. Opposing candidates might be fools, and they might get a lot of people hurt by accident with their foolish policies, but they aren’t evildoers, and they aren’t hurting the common good on purpose. Neither the candidates nor the voters are cooperating with evil.

It seems obvious that, under ordinary politics, every citizen ought to vote. We all have a duty to advance the common good. Under ordinary politics, voting does just that, with very little danger to one’s own soul. Therefore, the citizen generally has a duty to vote.26

Under ordinary politics, then, two things are true:

You, as a conscientious citizen, have an obligation to vote for the candidate you judge to be better, and

When deciding which candidate is better, there’s rarely an objectively right or wrong answer, because all of society shares the same basic view of the common good and disagrees only about the most effective means of achieving it.

These conditions prevailed in most27 of the United States throughout the middle of the twentieth century, culminating in the 1960s, the era of the “Great Consensus.” Catholics were a cornerstone of that consensus, and they became habituated to the voting mores of ordinary politics. So did nearly all Baby Boomers. They taught their children the ethos of ordinary politics, who taught their children the same.

The problem is that we have left ordinary politics far behind.

Extraordinary Politics

“Extraordinary” sounds like a big deal, right? It sounds like you should hit the alert klaxon and man your action stations. Ideally, that’s exactly what it is. There’s a crisis, the crisis ends, and normality resumes. But normality has a funny way of not resuming.

Let me tell you about something else “extraordinary” in Catholicism: the “extraordinary minister of Holy Communion.” The ordinary minister of communion in the Catholic Church is a cleric. However, during the first crushing wave of the priest shortage in 1971, the American Church requested and received special permission to allow laypeople to assist priests in ministering communion as well. Rome granted permission, then extended it to the rest of the Church in 1973. In 1983, the “extraordinary minister” was legally codified as a backup option. The priest shortage never ended. I was born in 1989. Virtually every regular Mass I’ve ever had half a dozen (or more!) “extraordinary” ministers. The crisis may simply fail to abate, and the crisis footing becomes the norm.

Something like this happened in U.S. politics during the 1840s and 1850s. Growing awareness of the horrors of slavery, combined with the Slave Power’s hardening determination to expand its reach into every corner of the United States (even free territory), catapulted slavery into the center of national politics. Gradually at first, then suddenly, every single federal election (and quite a lot of state elections) came to be about which candidate would do more to restrict slavery… or expand it.

There were other issues, of course. Everyone was desperate to maintain the veneer of ordinary politics. The most important bloc of moderate “swing” voters was really uncomfortable with slavery, but also felt, for various reasons, that it was necessary for slavery to remain legal. Those voters, especially, really did not want to have to think about slavery and really wanted politics to be about anything else. (You may know some people like this today.) Then, as now, people hated “single-issue voters,” for some reason, so they found excuses to pretend we were still in ordinary politics.

There was the great constitutional debate about Congressional funding for roads and canals; there was the dispute over annexing Cuba and the Ostend Manifesto; people were still arguing whether a Bank of the United States was a good idea. Naturally, plenty of people were mad about immigrants, who, at the time, were mostly hateful Romish papists invading New York City.

But chattel slavery was not one more ordinary-politics disagreement about how best to serve the common good. It was a direct attack on fundamental rights. It spat not only on the promises of the Declaration of Independence, but on the very idea of human liberty, equality, and dignity. Legal protection for chattel slavery was incompatible with the common good. Worse yet, this assault on fundamental rights was happening at scale. Four million souls—more than ten percent of the U.S. population—were “owned” by another human being. Even relatively “small” battles over slavery had enormous consequences for huge numbers of people. There were at least a couple hundred slaves28 in Kansas during the prolonged political struggle / low-grade civil war known as “Bleeding Kansas.” Their fates, and those of many others, were decided by elected politicians.

In the 1850s, then, slavery was not a “single issue” alongside the Ostend Manifesto and currency policy. Slavery was a singular issue, one that conscientious voters rightly considered preeminent in their voting decisions. If you voted for a presidential candidate who supported Kansas’s proposed pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, you were cooperating with evil. If you voted for a presidential candidate who positively supported the Fugitive Slave Act, you were cooperating with evil.29

The act of the public official who unjustly strips fundamental rights from a class of citizens is not merely cooperation with evil. It a very grave, direct evil in and of itself. Establishing a right to chattel slavery is bad enough to send a man to Hell, even if nobody takes him up on it by actually enslaving anyone. (Of course, somebody always takes him up on it.) The pro-slavery legislator enables other evildoers (a form of cooperation), but he is first and foremost an evildoer himself, no less than the rapist in our earlier examples.

Indeed, our rapist pursued the rape of only one girl. The pro-slavery legislator takes positive action to permit the rape of an entire race of girls.

So when a citizen voted for the evildoing legislator, cooperating in that evil, what moral burden did that citizen bear? Was this really bad cooperation, like holding down the rape victim? Or was it pretty justifiable cooperation, like shopping at a store that might sell wrenches unknowingly to mechanics who might fix rapists’ cars?

The Voter’s Moral Burden

Formal cooperation is, as always, right out. If you vote for a pro-Fugitive Slave Act candidate because you want to get those fugitive slaves back in chains, you are actively pro-evil and bear full blame for it. Or, suppose you are “personally opposed” to slavery, but you believe it isn’t your “place” to make that “decision” for others. You vote for the pro-slavery candidate because you oppose giving legal human rights to slaves. You are also formally cooperating in evil and bear full blame accordingly.

Let us suppose, however, that our hypothetical voter is a really good person. (Let’s call him Louie.) Louie is a (rare) supporter of complete and immediate abolition. Louie is voting for the slavery candidate, but despite those views, not because of them. Louie wants to put the slavery candidate in office for the sake of all the good things he will accomplish, like preventing recession through specie and maybe doing something about all those Catholics stealing our jobs. Louie’s cooperation is material, but not formal.

It is not immediate material cooperation, either. Louie doesn’t draft pro-slavery speeches for the slavery candidate, he doesn’t bring the bills to his desk to sign, he’s not right there directly helping the slavery candidate defend and expand slavery. Louie’s cooperation is more remote than that, since he is only voting for the slavery candidate.

How remote?

To answer, let’s go back to our examples of cooperation with rape. Remember the roommate, the mechanic, the cashier, and the hardware store customer?

Louie’s vote for a pro-slavery candidate most closely resembles the rapist’s roommate. (As a reminder, the roommate was the one who, knowing that the rapist planned to commit a rape, told the rapist exactly where to find his target.) Like the roommate, Louie is only one step removed from the lawmaker he votes for. The mechanic and the cashier were two, three, even four steps away from the rapist himself, but Louie’s support for the candidate is direct and unmediated.30

The rapist sought information—the location of his target. The slavery candidate seeks authorization—the legal power to enact his policy program. Both obviously contribute substantially to the evil. When the roommate gave the rapist that information, he gave the rapist specific material aid that substantially advanced his evil objectives. When Louie gives the slavery candidate his vote, that, too, is specific material aid that advances his evil plans. That’s what a vote for a representative is: an attempt to imbue a candidate with power to act, on your behalf, with legal authority.

The voter’s cooperation with the legislator’s evil, therefore, is very proximate. It is more remote than immediate material cooperation (which is always forbidden),31 but it is about as close to immediate material cooperation as an act can be without actually being immediate.32

How necessary?

Voting is a funny thing. You know how they sometimes give everyone in a firing squad a blank bullet, except for one guy, and nobody knows who? It’s a way of making each individual member of the squad feel less responsible for the execution. Voting’s a lot like that. As long as the election winner wins by more than one vote, every voter can tell himself, “Oh, phew, it wasn’t my ballot that did it.” Is it so easy? If I vote for an evildoer, is my responsibility for his evil acts diluted? Is that moral burden divided equally among every voter?33 If the evildoer’s legislation, policies, and court appointments are responsible for a thousand slave rapes that wouldn’t have happened otherwise, but 1.6 million voters joined me in voting for him, am I only responsible for… does some division… six ten-thousandths of a rape?

No.34

Remember our first rule of justifiable cooperation with evil, from a little while ago:

[T]here must be no reasonable way to obtain your intended good without the evil results. If there’s a way to get the good without the bad, obviously, you have to do that.

Louie is hoping that the slavery candidate will accomplish a great deal of good in office. Louie also knows that his specific vote isn’t going to matter, because a lot of other people are going to vote for the slavery candidate. Great! Let them! If Louie’s vote is not necessary to electing the candidate, then the good effects of the candidate winning will happen no matter what Louie does. Louie therefore has no reason to cast a vote for the candidate.

Of course, we never know in advance whether our vote is going to be necessary. Everyone has thought at least once about staying home on Election Day, and everyone has thought at least once, “Oh, no, but what if my staying home changes the outcome? What if I’m the reason Candidate X loses?” This is reasonable! In many voting contexts, it is unlikely (but plausible) that your vote could turn out to be the one on which the entire election turns. Hence the common argument among pro-voting activists: you always have to vote as though you’re casting the deciding ballot.

But this comes with a horrible moral responsibility: a vote to cooperate with evil can only be justifiable insofar as that vote is absolutely necessary. For the purposes of moral analysis, we must treat your vote as though it were absolutely necessary.

Louie faces a terrible burden. He wants the good things that the slavery candidate will accomplish, but, by voting for the slavery candidate, he would materially cooperate with evil. His material cooperation is so proximate it is nearly immediate, and it can only be regarded as absolutely necessary. If he does cast this vote, he will bear nearly full responsibility for the evil acts of the legislator once he takes office. Remember what we said earlier about the rapist’s roommate:

The roommate is so proximate to the rape, so necessary to its success, that he could only justify helping the evildoer if the evildoer were going to use his knowledge of the party to accomplish some good so great it would actually outweigh the rape (or very nearly so). The roommate’s contribution to the rape is too significant to be balanced out by anything less. However, I have no clear idea what good could plausibly do that, and I don’t care to contrive an example. This cooperation is so proximate, so necessary, so close to immediate cooperation, that it is probably only justifiable in theory and in off-the-wall hypotheticals, not in practice.

The United States Council of Catholic Bishops, in a document on voting ethics entitled Faithful Citizenship, put it this way:

35. There may be times when a Catholic who rejects a candidate’s unacceptable position even on policies promoting an intrinsically evil act may reasonably decide to vote for that candidate for other morally grave reasons. Voting in this way would be permissible only for truly grave moral reasons, not to advance narrow interests or partisan preferences or to ignore a fundamental moral evil. [emphasis added]

You can sort of imagine “truly grave” proportionate reasons if the candidate supports relatively small violations of fundamental rights. Like, maybe Candidate Smith “just” wants to put the five worst murderers in lifelong solitary confinement, such that none of them ever sees another human being again. Maybe you could reluctantly cooperate with that cruel and unusual punishment (which attacks the human dignity of five of the worst criminals), if Candidate Smith also opposed some much more widespread and fundamental attack on human dignity—like legalized wife-beating, which killed tons of women and was still being eliminated during the 1850s.

But this reasoning will not work for Louie, who is considering voting for a pro-slavery candidate. American chattel slavery was already a direct assault on some of the most fundamental rights, and few evils were more widespread. As we said earlier about the roommate:

Making this decision requires the potential cooperator to engage in a very ugly moral calculus. What would outweigh a rape? The hideousness of that question, and your natural instinct to recoil from it, is a good illustration of why Catholic moralists tend to treat cooperation with evil like it were glowing green nuclear waste.

What would outweigh one slave? What would outweigh two hundred slaves in Kansas? What would outweigh four million slaves nationwide? Is Louie prepared to answer that? Should he be?

Should you?

Yet this still doesn’t quite plumb the depths of how bad it would be to vote for the slavery candidate. Everyone who supported chattel slavery, by definition, rejected the basic principles underlying the common good. Such a person cannot be said to have any moral character, and cannot be trusted to do the right thing for its own sake in any context, big or small. Any good such a person might do would be essentially accidental. As one writer put it, when someone takes a public stand on questions of fundamental rights,

…he reveals his underlying vision of person, morality, law, and government. Unless is office is that of a mere functionary that can be filled by anyone with technical expertise, the candidate will have to bring his wisdom to bear on the common good in the execution of that office. This vision—this wisdom, or lack thereof—is by this fact the single most important qualification for holding public office. …We voters should never pretend that these issues sometimes do not matter in an election. They always matter. [emphasis in original]

To cooperate with a pro-slavery candidate, then, even if somehow justified, would leave the scars close cooperation always leaves. It would also create an enormous danger of toppling into formal cooperation yourself, as you struggled to rationalize the evil your vote caused. All this sacrifice to put a person in office whose moral vision is so defective as to render him untrustworthy on all issues. Yet the stakes here are not the country. The stakes are your soul. As the U.S. Catholic Bishops write in Faithful Citizenship:

38. It is important to be clear that the political choices faced by citizens not only have an impact on general peace and prosperity but also may affect the individual’s salvation.

Meanwhile—somehow we never got around to mentioning this—there’s an anti-slavery guy on the ballot! His economic plan is a bit rubbish, and you think his immigration plan is very unbalanced and will cause a lot of suffering, but, fundamentally, the anti-slavery guy is trying to bring about the common good. You know that especially because he doesn’t want to enslave the Black race.

Obviously, under these circumstances, you have to vote for the anti-slavery guy. If Louie votes for the pro-slavery guy, Louie will be wrong. Louie will have sinned. Louie might not realize it. (Louie isn’t very bright.) Louie’s ignorance might reduce his personal guilt… but it doesn’t remove the sin.35

Now, perhaps the anti-slavery candidate is pragmatic. He wants slavery extinct, but, recognizing the current political climate isn’t ready for abolition, he is willing to vote for compromises that help some slaves while leaving others in bondage. At least in Catholic thought, that is okay, as long as the compromises really are intended as temporary. As Pope John Paul II contended in 1995’s Evangelium Vitae, #73:

In the case of an intrinsically unjust law… [a] particular problem of conscience can arise in cases where a legislative vote would be decisive for the passage of a more restrictive law… in place of a more permissive law already passed or ready to be voted on. Such cases are not infrequent. …In a case like the one just mentioned, when it is not possible to overturn or completely abrogate a[n intrinsically unjust] law, an elected official, whose absolute personal opposition to [the injustice] was well known, could licitly support proposals aimed at limiting the harm done by such a law and at lessening its negative consequences at the level of general opinion and public morality. This does not in fact represent an illicit cooperation with an unjust law, but rather a legitimate and proper attempt to limit its evil aspects.

The anti-slavery candidate is still aiming at the actual common good, unlike his opponent. His tactical compromises may or may not be prudent, but they are not evil, and you therefore do not cooperate with evil by supporting him.

Under extraordinary politics, then, two things are true:

Just like in ordinary politics, you, as a conscientious citizen, have an obligation to vote for the candidate you judge to be better, and

Unlike ordinary politics, when deciding which candidate is better, there is usually an objectively right answer, because one candidate supports the basic concept of the common good and the other is advancing an attack upon its very core. All ethical voters must ordinarily vote the same way.

If you’d like to read more about the ethics of voting in periods of what I have termed “extraordinary politics,” you’re in luck: my father was among of the foremost Catholic thinkers publishing in this niche in the 2000s. I have borrowed liberally from him without credit, but he had much more to say that I have skipped for the sake of (believe it or not) brevity. I especially commend his longest paper, How Should Catholics Vote? (2007), although the much shorter More Than a Hill of Beans (2000) had more zest. (I stole the character of “Louie” from More Than a Hill of Beans.)36

However, my father’s work was shaped very strongly by the baseline assumptions of “extraordinary politics.” In 2024’s presidential race, those assumptions do not apply.

Ordinary Antipolitics

Suppose you are citizen of ancient Rome. You are voting for tribune, a public official with wide-ranging power to block or advance legislation. Both candidates have some pros and cons. You like Quintus because he promises to veto a proposed law against chariot races, and you love the chariots. However, Quintus is also proposing legislation to shift the costs of pothole repair from the aediles to local neighborhoods, which would be bad news for the bad roads in your poor neighborhood. Quintus’s opponent, Gaius, is the opposite: anti-chariot but pro-fixing-potholes. Hm, a classic decision for ordinary politics!

Except one little thing: both Quintus and Gaius support the (pretty brutal) institution of Roman slavery. Neither is running on it as a platform issue, because, unlike antebellum America, slavery is a non-issue in Rome. Everyone supports Roman slavery. (Everybody except you, anyway.37) The issue is simply settled. Your tribune is unlikely to face any pressure to take up new slavery-related legislation in the coming term, either pro- or anti-slavery. He’s almost certainly not going to originate any himself, since he shares Rome’s pro-slavery sentiment. He’s probably never even thought about it very much. It’s just reflexive.

In this situation, both candidates support an ongoing legal assault on fundamental human rights, rejecting the common good. However, the assault lacks salience. It isn’t an active political issue. The actual issues on the table in the election look a whole lot like ordinary politics, while this horrifying evil lurks in the background.

Ordinary politics prevail when the nation’s fundamental values are both shared and correct. Extraordinary politics prevails when the nation’s fundamental values are not shared. Sometimes, though, a society does share its fundamental values… but those values are Garbage McEvilpants. (One could make the argument that, throughout human history, this is the most typical condition of all.)

I’m going to call this “antipolitics.” Just as antimatter looks a whole lot like ordinary matter until you look closely (and explode), antipolitics looks just like ordinary politics if you don’t look too closely. Then you notice that your whole society is built on a foundation of children’s skulls (and explode). What choice does the conscientious voter have in Omelas?

In a society where a great evil is both established and (for now) wholly beyond the reach of politics, refusing to cast a ballot could be a valid form of protest against the great evil. So could casting a blank ballot. Both actions would protect the voter from the harms of cooperation with evil, and are therefore presumptively preferred.

On the other hand, the fact that the great evil has no political salience arguably limits the extent to which any given legislator or voter cooperates with it. A voter in 1856 America knew that, by voting for the pro-slavery candidate, he would (at least in a small way) be helping defeat anti-slavery legislation (and court appointees) and advance pro-slavery legislation (and appointees). A voter in Rome circa 177 B.C., on the other hand, probably doesn’t expect slavery to come up at all during the tribune’s term. This, at least arguably, attenuates the tribune’s level of material cooperation with the evil of Roman slavery, which limits the voter’s material cooperation as well.

There is at least a colorable case to be made that the conscientious voter could, under these circumstances, behave as though ordinary politics prevailed. He might be able to vote for the candidate likely to inflict the least harm, or most likely to pursue other goods. Even if the candidates have rejected the common good, the voter still knows what it is, and can perhaps use the candidates instrumentally to help imperfectly achieve that good vision.

In Faithful Citizenship, the U.S. Bishops offer only one cryptic comment on the moral dilemma of voting under antipolitics:

36. When all candidates hold a position that promotes an intrinsically evil act, the conscientious voter faces a dilemma. The voter may decide to take the extraordinary step of not voting for any candidate or, after careful deliberation, may decide to vote for the candidate deemed less likely to advance such a morally flawed position and more likely to pursue other authentic human goods.

This is not carte blanche to vote for the “lesser evil,” no matter how much partisan Catholics (on both sides) have tried to turn it into that. In fact, when we examine this paragraph, we find a lot of nuance crammed into its sixty words.

The first thing to notice is its reference to “all candidates.” This is interesting, because this was written by bishops in the United States, which has a two-party system. Most Americans would put “both candidates” here, but the U.S. Bishops deliberately use “all candidates.” This can only be a reference to third-party candidates, something we haven’t considered at all so far in this article. The U.S. Bishops appear to believe that, if any candidate embraces all the fundamental rights, that candidate should presumptively have your vote—even if that candidate has little or no chance of actually winning. This presumption can likely be defused by sufficiently grave moral reasons under some circumstances, but that case has to be carefully built, and is liable to hinge on a tricky prudential judgment.38 Until then, the presumption is that you ought to vote for the candidate who won’t make you, the voter, an accessory to murder, slavery, rape, or the like.

Given everything we’ve already discussed, this shouldn’t be a surprise. The voter’s first duty in the voting booth is not to make the tactically best choice. It’s important to try, but humans are terrible tacticians who are completely helpless at predicting the future anyway. The voter’s first duty is to protect her own soul.

However, perhaps the conscientious voter has no (good) third-party options, and lives in a state where write-in votes are not allowed (such as South Dakota). This is a true antipolitics. For such a trapped voter, the U.S. Bishops offer a choice:

The voter may decide to take the extraordinary step of not voting for any candidate or, after careful deliberation, may decide to vote for the candidate deemed less likely to advance such a morally flawed position and more likely to pursue other authentic human goods.

Once again, the presumption here is against cooperating with evil. “Not voting” is indeed an extraordinary step, but antipolitics is a situation beyond extraordinary. “Not voting” is listed first here and (unlike the other option) is given without qualification. Once again, this obviously follows from what has already been discussed. It is also the moral of “Omelas”.39

Nevertheless, the idea that you might ever have the option to not vote—never mind an obligation not to vote—runs strongly counter to every Boomer moral instinct about voting. In fact, I’ve come across more than one Boomer Catholic who quotes this passage to me as evidence that I must always vote for the lesser of two evils. It’s like their eyes just skip past the first fifteen words of the bishops’ choice, because it doesn’t fit into their view of the world!

This paragraph does preserve the option to vote for a “lesser evil” evildoing candidate (at least, as long as there are no good third-party options), but this short paragraph sheds very little light on when that option should be preferred over the presumptive option of simply refusing to vote at all. Many (many) (MANY) Catholics (on all sides) have interpreted this lack of explicit guidance as permission to vote for any “lesser evil” under any circumstances.40

However, if you have been following closely so far, you know this guidance isn’t here because it isn’t necessary. The Church’s rich teaching on cooperation with evil already supplies it. Cooperation is never required, and refusal to cooperate is usually morally praiseworthy, so “not voting at all” really should be seen as the default here. However, cooperation with evil through a vote for an evildoing candidate can be permitted—if, and only if, the voter can meet the exacting burden of proof to show that she is acting in the name of an even greater good that is likely to be obtained and which cannot be reasonably obtained by less evil means (such as by not voting).

Under antipolitics, ordinarily, this is juuuuust about possible. Because a society trapped in antipolitics has so fully embraced a violation of fundamental rights that it’s no longer salient enough to even have an organized opposition on the ballot, evildoing candidates do not (usually) have much to do with facilitating the evil, and they are not (usually) as committed to evildoing as you might expect. (They often haven’t thought about it very much. The evil is just The Way Things Are.) Since they aren’t so actively pursuing evil, the conscientious voter does not necessarily cooperate with evil when she votes for them.

Under ordinary antipolitics, then, the voter has these (very limited) obligations:

Since voting for any candidate would constitute cooperation with evil, the voter’s duty to vote (which is obligatory in ordinary and extraordinary politics) is suspended. Voting is only permitted if the cooperation with the evil is justified—which is hard to do, since voting is still pretty proximate and necessary material cooperation.

When deciding whether to vote (or for which candidate to vote), there’s often no objectively right or wrong answer, because society’s view of the common good is so uniformly deranged.

Unfortunately, we’re beyond this, too.

Extraordinary Antipolitics

Suppose Hitler and Stalin actually did face off in an election.41

At first, this might look like bog-standard antipolitics: both are super-evil dudes who are going to straight murder millions of people. Voting for either one of them would be big-time cooperation with evil.

There’s a big difference here, though. In regular antipolitics, the candidates support tremendous evil, but everyone agrees with it. The evil therefore is not salient.

By contrast, in Hitler v. Stalin: Dawn of Genocide, the two evils on offer are hotly contested. Hitler says he wants to kill all the non-Aryans. Stalin thinks that’s terrible. Stalin wants to kill the bourgeoisie instead. Hitler thinks that’s terrible. They both end up specifically running on their respective platforms. These two flavors of genocide end up highly salient.

In ordinary antipolitics, there’s a case to be made that, because the big social evil is lurking in the background with no salience, individual politicians may not be fully responsible for it, so maybe you can vote for them sometimes if the stars are just right. But Hitler v. Stalin is extraordinary antipolitics. Both parties embrace evil, but they are different evils, which they are mutually trying to inflict on a horrified populace, which makes those issues highly salient.

It’s easy to imagine how this might happen. Suppose one party is pro-slavery and the other party is anti-slavery. Normally, you would need to vote for the anti-slavery candidate. However, suppose it is revealed as an October Surprise that the anti-slavery candidate is a pedophile with multiple crimes to his name, and that one of the reasons he is running for president is so he can give himself a presidential pardon before the police close in on him. (Hi, Roy Moore!)

So now you have to choose between slavery and pedophilia. Fun! What’s the lesser evil here?

And, while we’re at it, which of your children should we send to the gas chamber? What’s the lesser evil there?

There probably is an objectively lesser evil, known only to God… but even the lesser evil is too goddamn evil for you to cooperate with it. This is not the situation that Faithful Citizenship #36 appears to be addressing. This is much closer to the situation addressed by Luke 23:20-25.

As I see it, the conscientious voter really doesn’t have much choice under extraordinary antipolitics:

If you can vote third-party, do so.

If not, stay home.

Do not choose a child. Do not trample the fumi-e. Do not play the Hunger Games. Do not hold down the rape victim, no matter how the evildoer threatens you. Do not hand over an innocent man to be crucified. And do not vote for either evildoer.

Here’s a second place where you can take a break, if you like. Then you can power through the rest of the article tomorrow.

Self-Diagnosis

Here are the four political configurations we have considered:

To be clear, I made up these labels. Nobody’s ever said “ordinary antipolitics” before today. Nevertheless, these configurations have all existed at one time or another, and you can see their contours in the various Catholic writings on voting going back a long time, even if the edges are blurrier than this diagram suggests.42

I think this is a good rubric. It’s not Catholic doctrine, but I’ve built it with a lot of help from Catholic thinking, and I do not think you need to be Catholic to see its wisdom.

I also think there were some past years that were fairly debatable under this rubric. For example, was Mitt Romney’s clear support for first-trimester abortions severe enough to turn the 2012 election into a year of ordinary antipolitics?43 If George W. Bush’s support for waterboarding had been known in 2004, would that have been a severe enough evil to turn the 2004 election into a year of extraordinary antipolitics? Did either man have moral character? These are interesting questions. There was a time when they were hot ones.44

But this is 2024. The question is no longer interesting. The answers are too obvious.

You’ve waited patiently, so, finally, let’s take a look at our candidates!

Kamala Harris is an Evildoer

There are many things very wrong with Vice President Kamala Harris. Even a partial list of reasons she would be a bad president would run so long it needs to go in a footnote,45 but I want to focus on her key policy issue, the issue she has tried to elevate to the highest possible salience: abortion.

There’s an easy way and a hard way to talk about abortion.

The hard way is to convince you that human rights begin when human life begins, at conception. This sends the dominoes falling quickly: it means abortion is (generally speaking46) murder, which means we are killing a million innocent children a year, which means legal abortion is a bigger human rights problem than slavery, which means voting for pro-abortion rights candidate in an election where abortion is a salient issue is very proximate material cooperation with truly extraordinary evil, which means it can be justified only in contrived examples, not in reality.

The hard way is important, and the pro-life movement needs to make more of an effort to do it. However, I don’t want to leave any of you with any excuse to vote for either of these people. I am therefore taking the easy way and talking about late-term abortion.

Nearly everyone agrees that late-term abortion is wrong. Abortion, for many people, is permissible because the child within isn’t truly human yet, because she cannot survive outside the womb and acts like a “parasite” upon her mother. For many others, abortion is permissible even if the child is truly human, because her existence imposes too great a burden on her mother’s autonomy and health. However, once a child has developed sufficiently to live outside the womb, most people agree there’s no difference between killing that unborn child and killing a born baby. An unwanted viable baby could be delivered, surrendered to the state, and given up for adoption, eliminating the burden on mothers’ autonomy. Even its strongest supporters admit that late-term abortion is nearly as dangerous as childbirth (and they’re exaggerating its safety) so there’s no general health reason to prefer late-term abortion to early delivery. The only reason for elective abortion at this late stage in pregnancy, then, is to kill your child (rather than give her up). This is, plainly, a violation of their right to life.

There is a small fraction of Americans who do not share this view, but it seems safe to say that either someone is lying to them or there is something wrong with them.

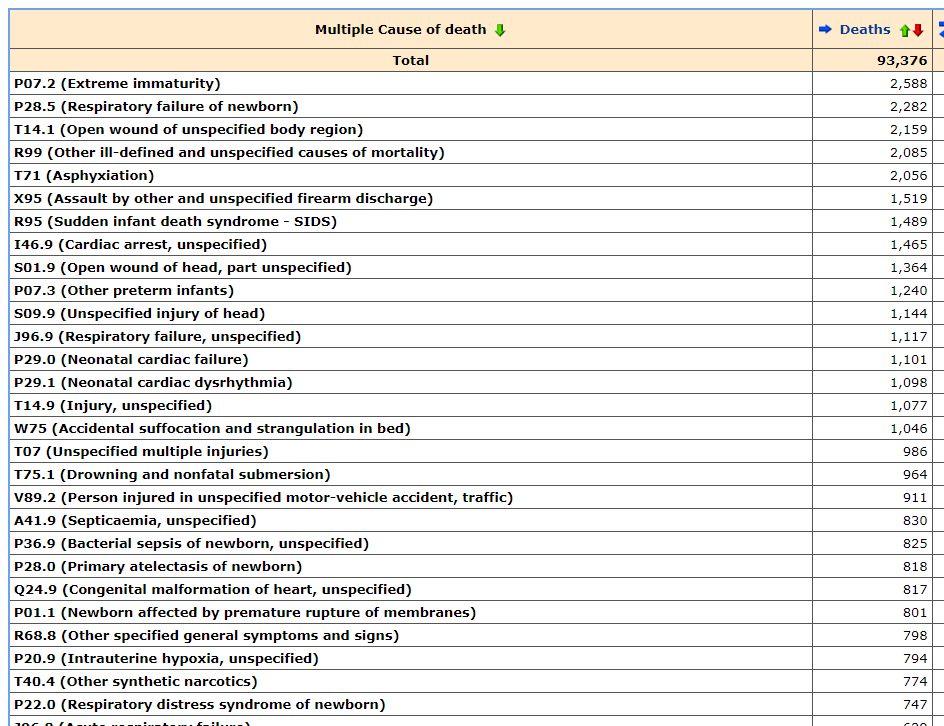

Abortions of viable children are rare. At 25 weeks, a preemie’s odds of survival are above 70%, so let’s use 25 weeks as our cutoff.47 Here’s the kind of baby we’re talking about here:

The best estimate available to me says that a little more than 0.5% of all abortions take place at or beyond 25 weeks.48 At first, that looks like a tiny fraction. However, there were almost exactly a million abortions in the United States last year, so this “tiny fraction” is still 5,100 dead babies.

Perhaps you have heard the common lie from Democratic office-seekers who promote late-term abortion: they say something to the effect that every single late-term abortion is a tragic case where either the mother or the fetus has severe health issues.49 However, state-level abortion-reporting data indicates that 80% of late-term abortions are not for those reasons. The limited studies we have suggest about the same, with around 80% of late-term abortions happening for approximately the usual reasons American women get elective abortions (money, coercion by the father, coercion by the family, fear of derailing one’s career, and so on). Even one of America’s leading third-trimester abortion providers agrees that “at least half” of his “patients” come without any “devastating medical diagnosis,” and are getting elective abortions. Kristin Hawkins recently showed how easy it is to schedule a 34-week abortion for any or no reason. To avoid giving you any excuses to dismiss this, we will use the most conservative possible estimate: we will say that just under half (49%) of these 5,100 late-term abortions are because either mom or baby is going to die if the pregnancy continues to term.

That still leaves 2,600 straight-up baby murders per year.

That makes late-term abortion the leading cause of death among all persons under the age of 18:

Do you support car seat laws for kids under 5? I do. The NHTSA estimates car seats saved 325 kids in 2017.

Meanwhile, we killed eight times that many viable infants who could have gone to loving homes.

Kamala Harris supports that.

She voted against the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act, which would have banned abortions after 20 weeks (except in cases where the mother’s life or physical health would be endangered or where the child was conceived in rape). Asked repeatedly whether she would support any limits at all, she repeatedly dodged the question. She often says that she wants to “restore the protections of Roe v. Wade,” which (as she knows very well) allowed abortion through all nine months of pregnancy for any reason (which is how we got to “murdering 2,600 babies a year” in the first place).50 She co-sponsored a bill in Congress to bulldoze all existing post-viability protections for the unborn—not to mention every other protection, from 24-hour waiting periods to parental notification or consent laws. Her running mate, my governor, Tim Walz, championed a law explicitly making third-trimester abortion legal in Minnesota with no term limits, no restrictions, and no alternatives.

She has never even renounced the Democrats’ 15-year battle to try to block the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003. That law outlawed a particularly gruesome method of abortion where the abortionist induced labor, started the birth process, and then went into the brain with a knife once the baby was halfway out of the birth canal. (Indeed, the Democrats in general have never renounced their opposition to this bill.) After Michigan repealed its own partial-birth abortion ban law last year, Harris campaigned alongside its architects and championed their work as a model.

The Vice-President doesn’t just want to allow this, which would be crime enough in itself. Attempting to strip the right to life from every viable baby in this country is clearly an evil with a gravity and scope that rivals any other great social evil the United States has ever allowed. Just a few centuries ago, removing someone’s legal right to live was used as a form of tacit execution, and she wants to apply that penalty to all four million or so children who will enter the third trimester of pregnancy this year, including in the subset of states that have passed laws to protect those children. Egads!

But Kamala Harris also wants you to pay for it. She is a strong supporter of taxpayer-funded abortions, fighting the Hyde Amendment (the bipartisan 1980s deal that forbade taxpayer-funded abortions) tooth and nail every chance she gets and abusing executive powers to invent new “exceptions” to it at every turn.

Perhaps you are coconut-pilled, which darkens the intellect, such that you aren’t seeing just how bad this is. So, an analogy.

I find Republican responses to school shootings pretty frustrating. They condemn the killer, promise thoughts and prayers for the victims, and mumble something about having more armed teachers and better mental health care before changing the subject. Fifteen children were killed in school shootings last year alone. The Republican response is inadequate, and does not seem to me to represent the correct prudential balance to ensure the common good.

Vice-President Harris’s response to elective late-term abortion is like if J.D. Vance co-sponsored federal legislation to repeal state-level bans on school shootings, while simultaneously pushing a plan to have the federal government buy every American a gun, no questions asked. When asked how this could possibly be a healthy response to school shootings, Vance explains that these are decisions that have to be left between an incel and his gun dealer, which he doesn’t have any right to second-guess. Vance describes the shooting as a tragedy, but, when pressed, he refuses to condemn the shooter’s actions, refuses to acknowledge the lives the shooter took, and appears to consider it a “tragedy” solely because of the pain suffered by the shooter, not the victims. When really pressed, he denies that school shootings ever happen, arguing that the Sandy Hook kids were crisis actors, and calls anti-school-shooting laws a distraction from attempts to take away our Second Amendment rights. (Tim Walz did the late-term-abortion equivalent of all this in an interview yesterday.) If Vance did all this—or any of this!—I hope you would agree it would be really evil, no matter how sweet Vance’s tone of voice was while he laid out his plan, and you really couldn’t vote for him, even if it were “only” 13 kids a year or so instead of 200 times that number. Credit to Republicans: they’ve fallen short on gun violence, but they’ve never done this!

In fact, you could never trust a person who said any of these things with public power. It’s not just that you would need to keep this hypothetical Vance out of the business of gun regulation. You would need to keep him out of any legal authority whatsoever. A man who thinks school shootings are okay has such a profoundly defective view of the common good that you could never even make him dog-catcher. “Such a person,” I said earlier, “cannot be said to have any moral character, and cannot be trusted to do the right thing for its own sake in any context, big or small. Any good such a person might do would be essentially accidental.”

At this point, some protest that Harris is unlikely to actually accomplish anything on the abortion front.51 Her powers over specifically late-term abortion are fairly limited in the Oval Office.52 She would (probably) need control of the Senate to abolish the legislative filibuster and start passing abortion legislation, and she only has a 27% chance of achieving that right now. But remember what we said earlier about this very problem:

One more thing worth noting: the evildoer might succeed at the rape, but he might well fail. The doorman at the party might think the evildoer has a shady look and refuse entry. The girl might come down with the flu and stay home. The evildoer might get caught trying to drug her and get kicked out of the premises. However, even if the rape fails, you have still engaged in proximate material cooperation with rape. Morally speaking, you are just as guilty as you would have been had he succeeded.

Sophie only helped kill one baby, and it destroyed her. If you vote for Vice-President Harris, you are helping kill many more. The fact that you might (might!) be stopping the other guy doesn’t blot that out one bit.

Maybe Kamala is the lesser of two evils. I think that’s plausible! (More on this in the next section.) Even if she is the lesser evil, though, she is engaged in an attack on the most fundamental human rights of so many innocents. There were fewer slaves in all of Kansas.

Your free choice to make yourself an accessory in her attack would be a very proximate and (from the standpoint of trying to justify it) absolutely necessary form of cooperation. The act would hurt you, badly. Not nearly as badly as it would hurt the babies, of course, but badly nonetheless! It would bind your will and corrupt your intellect, and you would deserve it.

So just don’t do it. In the bowels of Christ, I implore you: do not vote for Kamala Harris.

Donald Trump is a Criminal

I’ve written… God only knows how many words about Donald Trump since he came down that damn escalator nine years ago. At least a couple hundred thousand. Yet, in all those words, I’m not really sure I’ve ever said it better than I did in the very first thing I ever wrote about Candidate Trump, way back in “Unflattering Assessments of Presidential Candidates, 2016”:

If you need me to explain the problems with Donald Trump, you are one of the problems.

I will not list his many shortcomings, even in a footnote. How about a song?

NPR wrote this to be mean but joke’s on them I’m an unironic fan.

However, for those of you who still don’t see him as I do, I will more profitably direct you to two articles by pro-life Catholics Edward Feser and Steven Greydanus.53 Despite disagreeing with one another and with me on many points (including my main point), both make the case that it could plausibly do more harm than good to our cause if Trump were to win again. (Friendly reminder: Donald Trump is the most pro-choice Republican nominee in history.) However, since Harris is also pro-abortion, this is a prudential judgment. For my part, as with Harris, I’m going to focus on one highly salient political position of grave moral import that places Trump beyond the pale of justified support.

Now, in a sense, Trump doesn’t really have political positions. He has an ego, and he takes whatever positions in the moment support that ego.54 The bright side of this self-centeredness is that Donald Trump is not hell-bent on stripping human rights from anyone, least of all babies. He attacks human rights only when it’s good for his ego. The dark side is that, when his ego is threatened, he is capable of anything.

Like that time he directed an insurrection to help overthrow the United States Government.

I have written a few words about that effort. There is a distressingly large minority of Americans who do not share this view of the Capitol Insurrection, but it seems safe to say that either someone is lying to them or there is something wrong with them. As a right-winger, I admit that I like to think they have mostly been lied to. If you are in that fraction, I invite you to read my old article “The President’s Insurrection,” but, since you have already read rather a lot in this article, I will summarize:

President Trump knew, better than anyone else in the country, that he had lost the election. He nevertheless kept telling people he had won, even using specific examples that he personally knew to be false.

President Trump knew that some of the people coming to Washington were planning violence on his behalf.

He gave a speech that could almost be interpreted as being only accidental incitement if you ignore everything he did for the rest of the day.