Many writers propose constitutional amendments in order to demonstrate their fantasy vision of the perfect regime. In Some Constitutional Amendments, I propose realistic amendments to the Constitution aimed at improving the structure of the U.S. national government, without addressing substantive issues.

I think most of the footnotes in this one are pretty good. They’re worth reading, if only so you find out what the “unit rule” is. (I’m going to further discuss the unit rule in Part II, and I will assume you know what it is by then.)

It’s been a minute since the last installment of Some Constitutional Amendments. My plan was to use the next amendment on Senate reform. However, I think we should turn our attention to a grim milestone in American self-government: Donald Trump and Joe Biden have recently become the presumptive presidential nominees1 for the second time in a row, despite everyone hating that idea.

They have every reason to hate it. Neither Biden nor Trump has the qualities we need from a president. Neither is up to the challenge of “preserving, protecting, and defending the Constitution” from 2025-29. Indeed, neither of them seems to particularly like the Constitution, and one of them (guess) has worked hard to become the Constitution’s antithesis. How far we’ve fallen! Federalist No. 68 today reads like a sick joke:

The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. (lol) Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States. (rofl) It will not be too strong to say, that there will be a constant probability of seeing the station filled by characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue. (lmao) And this will be thought no inconsiderable recommendation of the Constitution, by those who are able to estimate the share which the executive in every government must necessarily have in its good or ill administration. (cmiaeg2) Though we cannot acquiesce in the political heresy of the poet who says: “For forms of government let fools contest / That which is best administered is best,” yet we may safely pronounce, that the true test of a good government is its aptitude and tendency to produce a good administration.

Fifteen years ago, I’d shake my head at these words. Eight years ago, I’d chuckle bitterly.

Today…? Today, it hurt to read this. It gave me a stomachache. Part of me wants to cry. In 2024, Federalist 68 isn’t funny anymore.

The presidential election process is broken. It has been broken for a lot longer than the past fifteen years. It was broken first by the Framers, then by the People, and finally by the Parties. It can only be fixed by returning to the source—the Constitution—and amending what went wrong in the first place. That’s what Some Constitutional Amendments is all about. Unlike previous installments in this series, though, I’m not starting out with my proposal. This time, I need to take you on a short walk through the history of the breakage. Only then will we have enough information to develop a proposed amendment.

The Electoral College: An Ingenious Fiasco

Here at Some Constitutional Amendments, we like failed Constitutional provisions. The Origination Clause was well-intentioned but a damp squib. The Apportionment Clause worked for a bit, but the wheels came off over the course of a century and now it’s dead in a ditch. Yet few provisions of the Constitution were more crucial than the Electoral College to elect the President—and no provision of the Constitution failed more completely, catastrophically, and above all instantaneously as the Electoral College.

At the Constitutional Convention, some of the Founders took their cues from the English system, where the Prime Minister serves at the pleasure of the House of Commons.3 These Founders wanted our President to be elected by our House of Representatives. Other Founders wanted direct, national, presidential elections.

The Constitution was exceptionally democratic for its time—far moreso than most state constitutions. It featured some radical innovations, including a nationally representative government with no property requirements, suffrage in House elections for the widest possible range of voters, and ratification by popular conventions.4 Yet a direct, national, democratic election for the presidency was a non-starter for several reasons. Here are some of them:

There was insufficient communication across the continent for voters to evaluate presidential candidates from other parts of the country, especially because the Founders (especially Washington) were trying to establish a nation that would be free of the scourge of national political parties.

Even today, there’s something to this. For most of us, most of what we know about most politicians outside our own region of the country is communicated by the letter after their name, and we judge them accordingly. The only thing I know about Jay Inslee is what I learned writing or publishing jokes about him for De Civitate—yet the “D” after his name tells me that I’d almost certainly sooner crash an A-Wing into the Super Star Destroyer Executor than cast a vote for him. Take away party endorsements, and how good would any of us be at choosing among candidates from a thousand miles away?A national direct election would mean top-down national control of elections in all their minutiae. Washington, not the states, would need to decide exactly who can vote, administer the election, count the ballots, and certify the results. Otherwise, states asked to “self-police” their presidential elections could and certainly would manipulate the results, in all sorts of amusing ways. (We’ll come back to this.) This was inconsistent with the federalist, state-driven republic the Founders were trying to establish.

It must be admitted: the slave states did not want direct elections because it would diminish their electoral power. In the House, they had successfully bargained to make every slave count as three-fifths of a person, meaning slave states got a dozen or more extra seats in the House. If they had to wage a national election on level ground, Southern free citizens against Northern free citizens, the North would outnumber the South. Slavocrats didn’t like that.

Democracy is the most unstable and therefore dangerous form of government, as philosophers and theorists have warned since Plato. Democracy has an uncanny ability to degenerate into tyranny, which the Founders feared above all else. (I used to have to make a complicated argument for this, but now all I have to do is remind you to look at our presidential candidates!)

The Founders wanted democracy, yes, but democracy as Aristotle had it: moderated through republican institutions under a republican constitution, like a stable nuclear reaction moderated by control rods. Without the control rods, you get Chernobyl. Without republican institutions, like Congress, moderating populist access to full executive power, you get the tyrants who brought down the Roman Republic—Sulla, Caesar—or any number of Greek tyrants. The Founders knew their classics! Moderns, too, should recall that Hitler won free and fair elections, and that perhaps the worst, bloodiest, most terrifying tyranny in the history of Europe (prior to the 20th Century) was the “democracy” vomited up by French rage in 1792 and sustained by murder until it subsided, with a sigh of relief, into Napoleon’s tyranny. If you’ve forgotten it, let John Adams himself remind you, in an excellent 1814 letter:

Remember Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes exhausts and murders itself. There never was a Democracy Yet, that did not commit suicide. It is in vain to Say that Democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious or less avaricious than Aristocracy or Monarchy. It is not true in Fact and no where appears in history. Those Passions are the same in all Men under all forms of Simple Government, and when unchecked, produce the same Effects of Fraud Violence and Cruelty. When clear Prospects are opened before Vanity, Pride, Avarice or Ambition, for their easy gratification, it is hard for the most considerate Phylosophers and the most conscientious Moralists to resist the temptation. Individuals have conquered themselves, Nations and large Bodies of Men, never.

…Democracy is chargeable with all the blood that has been spilled for five and twenty years. Napoleon and all his Generals were but Creatures of Democracy as really as Rienzi Theodore, Mazzianello, Jack Cade or Wat Tyler. This democratical, Hurricane, Inundation, Earthquake, Pestilence call it which you will, at last arroused and alarmed all the World and produced a Combination unexampled, to prevent its further Progress.

The Founders had already clothed the President of the United States in immense power, power unheard of in the history of American self-government to that point.5 They were very invested in creating the most robust, most open, most free, most participatory democratic-republic the world had ever seen. For exactly that reason, the President must not be directly elected by the People.

Yet election by the House had plenty of problems, too. I love the House—I love it so much I want to make it twenty-five times bigger!—but critics had a point. In England, the House of Commons wielded altogether too much power over the Prime Minister, so that they tended to act in tandem. Without adequate separation of powers, the Prime Minister and the Commons was all too easily able to assembly a tyranny of the majority. Indeed, this tendency has only increased in modern times. As the Commons has become more and more democratic and the Prime Minister more and more a partisan leader rather than a national statesman, modern Britain has become a terrifying, schizophrenic despotism which free people, on the whole, should endeavor to escape rather than reform. It’s weird that more people haven’t noticed this.

The Founders also worried about bribery.

So, stuck between two simple, precedented, but ultimately dangerous ideas, the Founders hit on a compromise that was vastly superior to both.

(…or, would have been, had it ever worked even once.)

It would be known as the Electoral College.6 Each state would appoint or elect their wisest, best, and most celebrated citizens to serve as presidential electors. This open-minded cream of the crop would then gather in small groups, one per state, and talk among themselves for a little while about who might make a good president. After a robust discussion, these top citizens would each vote for two candidates, seal those votes, and send them to Congress. Of course, because of the primitive state of interstate communication at the time, the Founders expected the electors would be very tempted to simply vote for local favorites. The Founders were fine with a little favorite-sonning, but added a requirement that every elector must vote for at least one person from a different state.

Once the votes arrived in Congress, Congress would count them up. In the unlikely event that a single individual commanded so much respect from across the United States that he won a majority of the electoral votes, then that man would become President. But, as Founder George Mason remarked, to general acceptance,7 “nineteen times in twenty,” no single candidate would command such broad national support. At that point, the final decision would be made by the House of Representatives, which would choose between the top five candidates. In effect, the electors would nominate, and the House would elect.8

This system had a lot going for it. The President would be appointed by good men and true, a diverse cast of leading lights from all across the states—big, small, rich, poor, old, frontier9—after respectful, spirited deliberations. These electors would assemble only once, owing their allegiance to no one in the federal government (least of all the new president!), with no incentive to show favoritism to any faction. If these electors were not elected directly by the People for this purpose, they would at least be elected by the state legislature, the elected representatives closest and most frequently accountable to the People. Indeed, some of the electors might be state legislators! The electors would truly represent the People. If they converged on a consensus candidate,10 their will would be obeyed. When the electors revealed no national consensus, the House, as the most democratic national body, would choose—but could only choose between the leading candidates offered by the electoral college! The House could not substitute its own (potentially corrupt) judgment.

As Hamilton wrote in Federalist No. 68, “[I]f the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent. It unites in an eminent degree all the advantages, the union of which was to be wished for.” All the strengths of direct election by the People and by the House, with none of the weaknesses! Hamilton went on:

It was equally desirable, that the immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice. A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.

It was also peculiarly desirable to afford as little opportunity as possible to tumult and disorder. This evil was not least to be dreaded in the election of a magistrate, who was to have so important an agency in the administration of the government as the President of the United States. But the precautions which have been so happily concerted in the system under consideration, promise an effectual security against this mischief. The choice of SEVERAL, to form an intermediate body of electors, will be much less apt to convulse the community with any extraordinary or violent movements, than the choice of ONE who was himself to be the final object of the public wishes.

Hamilton could not have been clearer: one of the most important functions of the electoral college was to protect us from the “convulsions” of a national, direct election by the open, unchecked passions of the mass of men. As Adams already reminded us, that’s how you get tyrants. The Electoral College protects us from an executive elected directly by the masses, and therefore from tyrants.

There was only one problem: it did not work, and it never could have.

A Bad Patch: The Twelfth Amendment

In the original electoral system, electors cast two votes, both for President. The runner-up became Vice-President. In the first election, there was a very broad11 national consensus that George Washington should be President and John Adams Vice President. So, if you’re an elector, what do you do? You cast your first vote for Washington and your second vote for Adams. The other 68 electors all do the same thing. Result? Uh-oh! Both Washington and Adams would end up with exactly 69 electoral votes, a tie! Instead of Washington winning the presidency outright, the election is thrown to the House! That’s not how it’s supposed to work!

Fortunately, Alexander Hamilton and a few others ran around the country convincing some (but not all) electors to divert their second votes from Adams to other candidates. This ensured that Adams received less votes than George Washington (but still enough to become Veep). This was silly and embarrassing, but not disastrous.

Then political parties emerged, and it got a whole lot worse.

The Founding Fathers naively believed that powerful political parties (or, as they called them, “faction”) were a sign of an ailing democracy, one they could avoid. Worse, the Founders believed that a large republic would automatically bring about a multi-party system with weak political parties. They did not understand that two-party systems are generated by voting systems, not geography. The voting method used in Colonial America (the guy with the most votes wins the seat, aka “single-member plurality voting”) guaranteed that we would end up with a two-party system and strong political parties, because of Duverger’s Law. Alas, the Founding was fourscore and thirteen years before anyone started to realize this (Mr. Duverger was born in 1917), so the Founders didn’t know that! They assumed there would be no well-coordinated national political parties in the United States. Oops!

This mistake keeps coming up in Some Constitutional Amendments, because, well, it was kind of a biggie! A lot of constitutional provisions that would have made sense in a country with dozens of tiny, uncoordinated, regional political parties simply do not work in a country with exactly two strong, national political parties.

This became obvious as soon as there was a contested election for President. After George Washington retired, the Federalist faction coalesced around John Adams for President and Thomas Pinckney for Vice President… although some Federalists preferred Pinckney for President. In the Democrat coalition, Thomas Jefferson emerged as the presidential candidate and Burr as veep. The election was complicated: Nine state legislatures directly appointed electors.12 Eight states held some form of popular election, but only for individual electors, many of them unpledged.13 No one voted directly on ballots for “Jefferson” or “Adams.” In the end, there were 70 more-or-less Federalist electors, 67 more-or-less Democrat electors, and one guy in Maryland who voted Adams-Jefferson, just to mess with historians.

Now imagine the Democrat electors had foreseen that they were going to lose to the Federalists. Instead of voting Jefferson-Burr, they could have tactically voted Jefferson-Pinckney. This could have inverted the Federalist ticket and made Pinckney the President over Adams! Another risk: Pinckney’s supporters might have told the Adams people they were going to vote Pinckney-Adams, but then secretly voted Pinckney-Washington instead. This would have reduced Adams’ vote total while buoying Pinckney, which might put Pinckney ahead of Adams and give him the Executive Mansion—or Adams supporters might double-cross Pinckney supporters and end up accidentally making Jefferson the President after all! Or the two factions might “throw away” votes inefficiently, resulting in Adams winning the presidency and his hated enemy Jefferson becoming vice president! Wouldn’t that be ridiculous?

…and that is exactly what happened. Adams won the Presidency, but Jefferson beat Pinckney for second place and became Vice President to a commander-in-chief he bitterly opposed.

The election of 1800 was even closer and bitterer. (A national “convulsion” if ever there was one.) Naturally, the Electoral College shenanigans only got worse. That year, the Democrats ended up with more electors. After watching the Adams-Jefferson fiasco for four years, the Democrats now tried too hard to make sure their chosen Vice President won the vice presidency, and, oops, the winners, Jefferson and Burr, tied in the electoral college! This threw the vote to the House, which, thanks to Federalists in Congress playing saboteur, immediately deadlocked. Thirty-six ballots later, with a real risk that Adams might continue in office beyond the end of his term, and rumors of civil war, the Federalists finally caved and let Jefferson take office. But what a mess!

Congress and the states needed to pass a reform bill before the 1804 presidential election, and they did: the Twelfth Amendment required electors to cast one of their votes explicitly for President, and the other vote for Vice President. This ballot designation would end the messy tactical voting where partisan electors had to decide whether to vote for their preferred Vice President (and risk an electoral college tie) or throw their second vote away (and risk losing the vice presidency to the other faction).

However, this ballot designation also permanently entrenched the party system in the electoral college.14 Never again would the electors function as a deliberative body. After the Twelfth Amendment, the electors swiftly became functionaries. Whether placed there by their state legislature or by voters, their purpose was to vote for one partisan ticket or the other—not all that ancient gobbledygook about having “wise citizens” participate in “robust discussions” about what might actually be good for the nation. Instead, the wise and prudent decisions envisioned by the Constitution gave way to the violent, public convulsions of negative campaigning and mob sentiment that the Founders had always feared.

Worse: because the President came to be (effectively) directly elected, he also gained more political legitimacy (the revered presidential “mandate”), which the presidents were able to gradually cash in for greater and greater executive power. The system of checks and balances our Founders imagined lies today in dysfunctional shambles, because (as I’ve discussed before), the Executive branch has utterly defeated the Legislative branch, which is exhausted and barely operational. Our quadrennial presidential election, which was never supposed to happen, has fueled that breakdown.

Once a keystone in the constitutional firmament, the post-Twelfth Amendment electoral college instantly became a weird anachronism. All the action and deliberation happened elsewhere, as the parties themselves, not the presidential electors, asserted control over who got to be on “their ticket” every four years—and the People were blessed-slash-doomed to hold bitter, divisive national popular elections where they chose between the two tickets.

So how did the parties pick their tickets, once the electors were no longer doing it?

The Original Smoke-Filled Rooms: 1800-1824

In those early years, presidential candidates were simply chosen by the party’s representatives in Congress. The Federalist and Democrat party caucuses in the House and Senate gathered together and voted to decide their party’s respective nominees for President and Vice President. That was that. These nominating caucuses began even before the Twelfth Amendment, by 1800, because the need for parties to “manage” their electors had already been made clear by the Electoral College’s bizarre failures in all of the first three presidential elections.

The nominating caucuses worked reasonably well. Although we still faced the national misfortune of a head-to-head presidential mass mob election every four years, at least the congressional caucuses ensured that the quality of the candidates was pretty high: DeWitt Clinton, James Madison, Rufus King, George Clinton, Elbridge Gerry, and James Monroe were all national candidates under this system.

However, by 1824, the People had decided that this system was unacceptable. It violated the separation of powers by giving the legislative branch a major role in choosing the head of the executive branch. It was (according to detractors) prone to intrigues and corruption. Above all, many citizens did not want their presidential candidates to be picked by their elected representatives in Congress. They wanted a more direct role. The popular desire for More Democracy, like a river flowing past a mountain, tends to erode any republican institutions set up to moderate it. So, in 1824, partisan state legislatures attempted to wrest the power of nomination from Congress, leading to chaos: no candidate won a majority of the electors and the election was thrown to Congress, which had to choose between not two candidates but four. It was all settled amid political intrigue (as it always had to be), provoking cries of a “corrupt bargain.” In the face of voter outrage, the Congressional caucuses simply stopped meeting. They never attempted to nominate candidates again.

(Enjoying this post? Click the button to subscribe for free for more. Or for money for even more than that!)

The Convention System: 1830-1972

For most of American history, the parties nominated their own tickets. This replaced the actual political function of the Electoral College, and left the College sort of pointless. However, although the parties replaced the College, the way they selected candidates bore a remarkable similarity to the original plan for the College.

At the start of a presidential year, you would get together with your politically likeminded neighbors in a gathering called a “caucus.”15 At the caucus, you would help elect a few of your wisest, most charismatic, most trustworthy neighbors as state delegates. These were your neighbors and fellow party-members; you knew them well and could judge who would do a good job representing you as a delegate. Those elected would then travel to the state convention, where delegates from all over the state would gather, each representing the members of your party from other towns and districts.

At the state convention, state delegates would discuss party business, finances, and policy, and would hold internal elections to decide who would get to run as your party’s candidate in major races (like for governor). Finally, in presidential election years, the state convention would elect its wisest and savviest (typically its top political office-holders in the state) as national delegates to attend the national convention. Since state delegates were often the same year after year (as long as they kept their neighbors happy!), these state delegates were well-positioned to know who would do a good job representing their values as a national delegate.

At the national convention, all the national delegates from every state gathered to discuss the party’s future. These would be the crème de la crème de la crème, representing the full diversity of the party: the wisest and best national delegates, chosen by the wisest and best state delegates, chosen by their neighbors in every district in every state. These chosen few would have to collectively set a national party platform and then collectively choose a presidential candidate.

At the start of a national convention, you often had no idea who was going to win. Delegates often showed up undecided (this was a time when you might literally have never seen or heard any of the candidates speak before, though you would probably have read some of their speeches in the newspapers), and engaged in fierce debate, which often lasted several days, punctuated by an official vote every few hours to see where people stood. (A bit like a papal conclave.) As it became clear that this candidate or that one was non-viable, delegates would change their minds, shift their votes to more viable candidates, form alliances, make deals, spread lies and gossip, and—ultimately—the delegates would elect a single presidential candidate.

There was one consistent rule that was always followed, which guided everything else about the convention: to be the official presidential nominee, you couldn’t just win the most votes on a convention ballot. You had to win an outright majority of the votes. Otherwise, you’d keep voting until someone reached 50%+1. (The Democrats set the bar even higher: until 1936, they required two-thirds of the delegates to agree on a single nominee.) This was a pretty good process: this system nominated Abe Lincoln (after four ballots), Calvin Coolidge (one ballot), Dwight Eisenhower (two ballots), Barry Goldwater (one ballot), and F.D.R. on the Democratic side (four ballots)… often after electoral “floor fights” between different party factions.

Overall, the caucus-convention system did a good job honoring the Founders’ ideal of free citizens electing their wisest and best people as representatives, and then having those representatives deliberatively decide who should be President. Perhaps the biggest drawback with this nominating system was that the Founders’ vision made the entire American people part of that deliberative process (through the votes they cast for elector and state legislator). The caucus-convention system was open only to political party activists. This slanted the nominating process, making the parties more likely to nominate candidates responsive to minority concerns from the parties’ activist bases. However, this slant was held in check, because one of the virtues the national delegates were chosen for was prudence. National delegates were determined to win presidential elections, and prudent enough to know how far they could push a partisan agenda without risking victory. They would often hedge toward a more moderate candidate with wider appeal—think Eisenhower or Lincoln.16

The other drawback, of course, was that, after the relatively deliberative caucus-convention seasons, we continued to host convulsive, tumultuous national elections every four years, where the mob might very easily deny the presidency to a candidate for sweating too much or because of an unfair attack ad. The system was not great, not terrible.

On the other hand, it was slowly getting worse. A 1972 commission led by Sen. George McGovern found that, by 1968, some twenty states had no official written rules about delegate selection, which (in practice) gave party leaders disproportionate power to pick delegates. Powerful party members routinely abused proxy voting to defy the will of their own delegates. In “several states… secret precinct caucuses” were “common,” so that regular neighborhood Democrats didn’t even get the chance to elect their wisest and best neighbors as delegates. State parties routinely imposed large fees and dues on delegates at all levels, further freezing regular voters out of the selection process. Corruption had crept in and needed to be sliced out with a scalpel.

Instead, for our sins, God gave us a nuclear bomb named George McGovern.

Blame George McGovern: 1972-Present

1970s Democrats were fed up with a lot more than the corruptions I just mentioned.

The caucus-convention system, even when it was healthy, tended to give “party bosses” a lot of influence, since they were often elected as delegates. Party bosses were often the ones who ended up in “smoke-filled rooms” during deadlocked nomination fights making compromises and cutting “back-room deals” in order to get consensus on a single nominee. This is obviously necessary and inevitable in any political nomination system where you need majority support to win. Disparate factions are going to have to compromise, and compromise will have to be negotiated.

Nevertheless, voters felt there was a lot of “corrupt bargaining” going on. They demanded a greater say in who their delegates were and how they voted. (The river of democracy erodes a little more of the mountain.)

After the disastrous 1968 Democratic National Convention (this ‘un), the Democrats convened a commission to “fix” this and other perceived problems with the nomination process. In 1972, the McGovern-Fraser Commission released its report, Mandate for Reform. The McGovern-Fraser Commission does not appear to have intended to burn the entire caucus-convention system to the ground. Nevertheless, the McGovern-Fraser Commission did in fact burn the entire caucus-convention system to the ground.17 It did this in three main ways:

The reforms strongly incentivized states to abandon traditional caucus-conventions in favor of binding primaries.

The reforms caused traditional caucus-conventions to functionally become binding primaries, only way more complicated and annoying.18 This reinforced #1.

Binding primaries were more amenable to media horse-race coverage, and media loves the horse-race, which led media to cover even actual caucuses as if they were binding primaries, which reinforced #1 and #2.19

The result is the modern nominating system, aka The Primaries, aka Hell.

Now, presidential primaries were not a brand-new invention in 1972. Like California ballot referenda and popular U.S. Senate elections, primaries were invented during the Progressive Era.20 In a presidential primary, voters didn’t meet or talk to their neighbors at all. They walked into a voting booth and cast a vote for a delegate to the national convention, bypassing the caucus-convention system entirely. Sometimes the state skipped the “delegate” part entirely and just let you vote directly for a presidential candidate. The winning candidate(s) would then choose the state’s delegates.

However, until 1972, the presidential primaries didn’t really matter. Only a few states held them. Some of those that did didn’t actually use the results to control delegates. (These were so unserious people called them “beauty contests,” although John F. Kennedy famously used them in 1960 to prove to skeptical party elites that a Catholic could actually win Protestant votes.) The balance of power remained firmly out of the reach of direct democracy.

After 1972, the presidential primaries were all that mattered.

The Transition

To be sure, it took time. Decades, actually! For example, the Democratic Party’s Iowa caucuses evidently continued to function as actual caucuses into the 1980s. However, at some point21 between 1980 and 2000, the Iowa caucuses became functional primaries, and all true caucuses are long-since extinct on the Democratic side.

Change came slower on the Republican side. The Iowa Republican caucuses were still true caucuses all the way to 2012. In 2016, they switched over, along with most other surviving caucus states.

There is an illustrative story there.

One of the recurring themes in the 2012 Republican nomination battle was that the caucus-convention system is about organization and persuasion. Candidates’ supporters have to show up, talk to their neighbors, win over their neighbors, and advance through several levels of party debate to secure support. (The McGovern reforms also made caucuses more vulnerable to activist takeovers.) In order to succeed in caucuses, candidates have to make a strong, deep case why they’re the right candidate to carry the party banner, and they need to command a loyal, competent organization.

Primaries are a lot simpler. To win a primary you need only two things: high name recognition and massive amounts of money. You aren’t trying to persuade deep, thoughtful, experienced partisans that your positions are right on the merits and that they can win over a general electorate. In a primary, you’re trying to excite/infuriate low-knowledge, low-interest voters so much that they’re willing to go stand in a booth for 12 seconds to fill out a ballot for you. Just like in the general election, primaries are more often decided by gaffes and memes than by actual substance. In a primary, the soundbite is king. Also: money. Gobs of money. You need to plaster your face on every gas pump ad screen from Dixville Notch to Seabrook Beach so those couch potatoes know who to vote when they roll themselves to the polling station.

You will be totally unsurprised to learn that, in the 2012 Republican nominating contests, Bain Capital founder Mitt Romney did great in primaries and did terribly in caucus-conventions. After the caucus-savvy Rick Santorum22 dropped out, you would have expected Romney to start winning caucus-convention states, since Romney’s main competitor was gone. Nope! Instead, well-organized fringe candidate Ron Paul started sweeping the caucuses! Paul won enough delegates this way that, under the Rules of the Republican Party, he was entitled to give a prime-time speech on the floor of the convention—even though he never endorsed Romney.

Romney was outraged about this, beside himself with fury at this stupid, weird upstart and his… checks notes droves of excited, young, right-leaning supporters. So Romney cheated. Straight-up. In blatant violation of the GOP rules, he and his cronies foisted a new set of rules on the GOP.23 The new rules effectively outlawed actual caucuses until fairly late in the primary season, and made it much, much harder for candidates to win meaningful numbers of delegates through caucuses. Primaries would henceforth be king in the GOP. (Iowa Republicans dutifully changed their caucus to function like a primary soon after.) Frontloading the primaries was intended to make it easier for Romney to win re-nomination in 2016, while running for his second term.

Of course, there was no “second term” for Mitt Romney, because he lost. These corrupt new pro-primary rules never ended up helping him. They ended up helping somebody else—a different guy with high name recognition, massive amounts of money, and huge personal liabilities that weighed him down in caucuses. His name was Donald J. Trump.

Trump excelled in primary states, where he hugely excited marginal voters who (apparently) were fooled by Trump’s claims of great business acumen and straight-shooting honesty. Trump was slaughtered in caucus-convention states, where more engaged party stakeholders saw right through him. But there were almost no caucus-convention states left, and those that remained couldn’t put up enough delegates to stop Trump’s rise to the GOP nomination.

I’m pretty sure Mitt Romney hates Trump more than he hates anyone in politics. Yet Mitt Romney is responsible for inflicting Trump on our politics, because he cheated in 2012 out of sheer spite for Ron Paul voters. The irony could not be more delicious. It’s just a shame we all are stuck with the orange-skinned consequences.

This was but one chapter in the long, losing battle to save the caucus-convention system from the primary. Stories like this have played out many times, in both parties, since 1972. The McGovern reforms made it so the only answer to problems was more primaries, and that’s why everything is primaries now.

And primaries are why everything is awful now. We want three things from presidential candidates: loyalty to American law, competence to carry out the duties of the office, and good character (so he makes good decisions that help Americans).24 Primaries do a horrendous job identifying these qualities. Instead, they favor sophist demagogues, aspiring dynasts, wealthy celebrities, dirty tricks, and lying liars.25

Adding insult to injury, primaries make the campaign season endless. I love politics, I love polls, I love Nate Silver, and even I’m sick to the teeth of the presidential horse race. Even Nate Silver is sick of the presidential horse race.

In the pre-primary world, Dwight D. Eisenhower was serving as Supreme Commander of NATO in Europe for most of 1952. He returned home in June to campaign for the GOP convention in July, which he won. (This is an extreme example, I admit.) Today, in the world of primaries, to have even a chance at winning one of the vital first three states, you really have to start campaigning by the middle of the previous year. Many commentators have blamed Ron DeSantis’s loss on the fact that he didn’t start campaigning for the 2024 nomination until “way too late.” DeSantis declared in May 2023, more than a full year before the convention! And they may very well be right that, in today’s primary-driven world, that’s too late! We have constructed a system where every presidential election lasts a minimum of 18 months. That’s the primaries.

Sustaining a campaign for that long, while paying for all those media hits, costs vast sums of money. That’s why your phone is glutted with spam fundraising texts right now. That’s why major presidential candidates are having to kowtow to big donors all the time. It didn’t used to be like this! If you take all the spending in the 1964 presidential election cycle—which surprised the nation with its extravagant overspending—and adjust that number for inflation, it turns out that the 1964 elections cost about $184 million. The 2020 election cycle cost $5057 million.26 That’s not all primaries. But some of it’s primaries!

And at the end of all those months, years of campaigning, all that fundraising, all those attack ads, what do we get?

Donald J. Trump and Joseph R. Biden.

That’s the best we can do, because, at full power, that’s what the primary system is designed to give us.

It then hands the nominees over to a national nearly-direct popular election, with all the bad judgment, bad character, corruption, expense, and tumult it generates. Our reward for surviving this ordeal will be one of those wretched men will become the most powerful man on Earth. Better and better: because our democratic “mandate” will have elected him, he will assert slightly more power than he did last time he was in office, just as every popular presidential election has fueled the imperial presidency and the decline of our republic. Didn’t Plato call this 2,500 years ago?

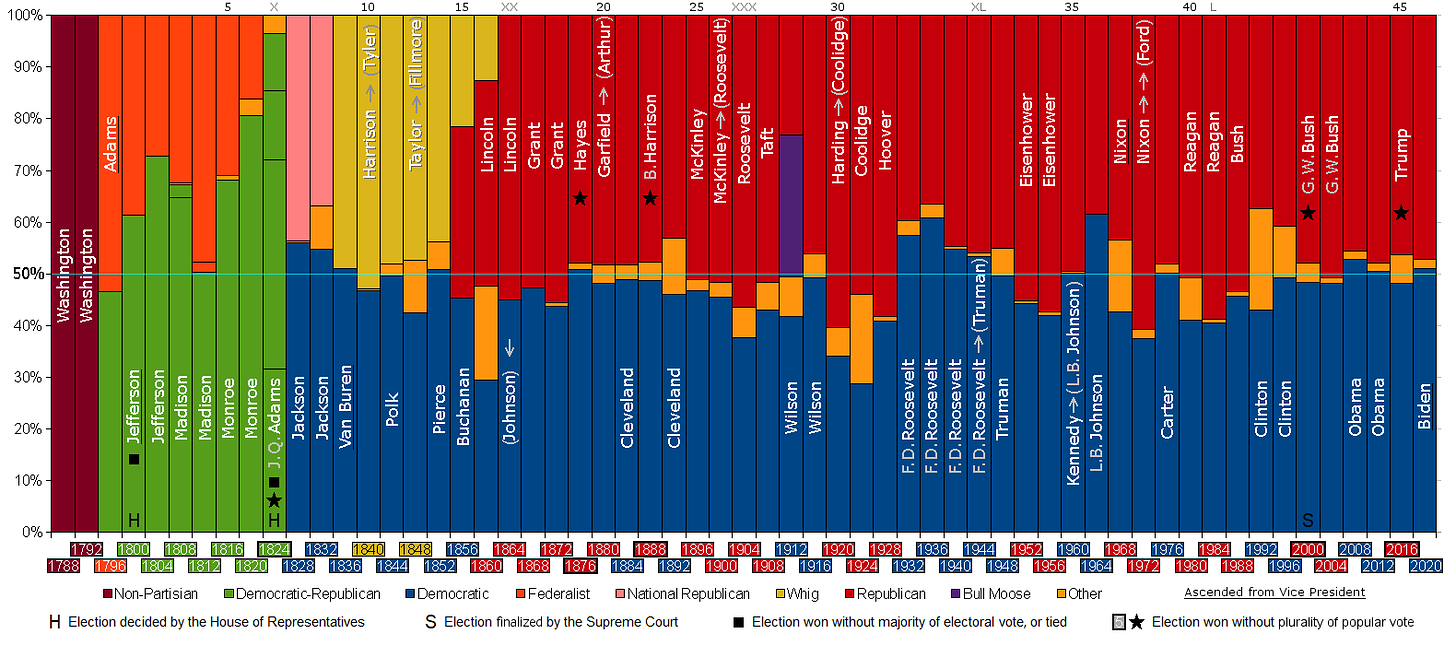

America has tried four different systems for electing presidents. Our current method is, far and away, the most democratic. It is also, far and away, the worst. This is no way to elect a president. We need something else.

Sorry, Al Smith: the cure for the evils of democracy is less democracy

It’s clear where I’m heading here: it’s time to abolish the Electoral College. It never worked correctly, and the other institutions we’ve improvised to handle the failure of the College are bad and getting worse.

When most people say that they want to “abolish the Electoral College,” what they mean is that they want to replace the Electoral College with a direct, national, popular vote. This is a noble instinct, one that belongs naturally to every citizen in a republic. It is natural to think that, if we are to govern ourselves, we ought to govern ourselves directly, without intermediaries between ourselves and our own sovereign power. We the People are the source of all legal authority in this nation, so why don’t We the People pick the President? Many of the Founding Fathers wanted to do this, and one of the biggest obstacles to doing it in 1787—the technology to communicate across a continental society—is undeniably solved.

The popular-voters have an ingenious plan to make it happen, too, something called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. I really admire this thing. The NPVIC, which has currently been adopted by 16 states (and D.C.) uses some obscure provisions of the Constitution to bootstrap a national direct election, without the need for a constitutional amendment, by winning agreement from individual states. It’s a brilliant piece of lawmaking, totally by the book, and I think the legal challenges to it are baseless.

I don’t actually support NPVIC, though, because, however noble the impulse, a national popular presidential election is (with respect) an insane idea. It was unhinged when (brilliant) Founding Father James Wilson proposed it, and it’s deranged today.

First, consider the political implications of everyone’s vote suddenly mattering. Do you think that would mean presidential candidates would suddenly care about your sensible, well-reasoned voting preferences? No! Convincing an undecided voter in Pennsylvania to swing over to your side is difficult and expensive. Convincing disengaged rabid partisans in Texas and New York to come out to vote is cheap and easy.27 Today, persuasion and turnout both play pretty important roles, but persuasion has the upper hand. Because the Electoral College hinges on outcomes in a few key purple states, it forces politicians to at least pretend to care about the concerns of the purple middle.

In a national, direct election, that incentive goes away! Turnout becomes the name of the game. Under the Electoral College, you have to win 50% + 1 in a majority of states. In a popular vote system, that’s an option, but it’s probably easier to win with 75%+1 in a handful of highly populated states (with dense advertising markets) while getting 25% everywhere else. (I went on about this at some length in a 2012 article.) Direct national election, especially given our terrible primary system for nominations, would take our current levels of polarization, acrimony, and extremism and turn ‘em all up to 11.

Second, remember the Founding Fathers’ warnings about the dangers of excess democracy. I won’t repeat them here, but remember how institutions moderate democracy the way boron moderates a nuclear reaction. Look at the conduct of our current presidential elections. Look at how often history has hammered home the dangers of direct democratic control over the chief executive. Heck, just look across the pond at Europe right now! They’ve got even more democratic democracies than we do. How’s it working out for ‘em? Not so hot, babes! Every time France is in the news, it’s either because another riot spun out of control, or because the neo-Nazis—not the Trump GOP, which is bad enough, but the actual neo-Nazis—are at serious risk of winning a national election. Same in half-a-dozen other Western European countries. More voting is not going to save us from the global democratic decline into madness. It never has. The Founders thought about the Roman Empire often enough to know that without having to see modern democracies in decline.

Third, remember how close we came to civil war in the 2020 election. There were several things that saved us from spiraling down the road to war that I laid out in August 2020. The big one: Biden won by sufficiently wide margins to protect the outcome from grave doubt. But another big one: to reverse the election outcome, Trump had to reverse the final results in four separate states. It wasn’t enough for him to find 100,000 votes in Arizona. That would flip Arizona, but it would do Trump no good in Wisconsin. Thanks to the Electoral College, election contests are contained within the states where they occur, like ice cubes in a tray. If one ice cube gets contaminated, the other ice cubes are unaffected. However, in a national election, every campaign would be looking for votes everywhere. There is no separation. Do you want every close election to end in a national recount? Do you trust California to recount fairly? Do you trust Mississippi? Speaking of which: in a world where vote margin actually matters, do you trust Mississippians not to start intimidating and threatening voters from the opposite party to stay away from the polls? Do you trust New Yorkers? Even if you do personally trust them all (good job!), you surely recognize that the rest of our society is incapable of extending that level of trust to “enemy” states right now.

That brings us to our fourth concern, one the Founders shared: federalism. Under the Electoral College, states administer their own elections. In a unified national election, states couldn’t do that anymore.28 The problems above would create too much strain. If we even survived our first 50-state recount, the aftermath would necessitate uniform rules, uniform control, uniform procedures, all steered by—God help us—the United States Congress. The election would ultimately be administered by the President of the United States, who may well be a candidate in the election himself. One of the few institutions Americans still trust is their local polling office, and the country schoolmarms and telephone sanitizers and half-blind retirees who volunteer to staff it. Our elections work in large part because, even though many of us don’t trust the rest of the nation’s election system, we do trust the guys down the block to count every vote fairly. Now imagine that entire system replaced by top-down federal control, run by the guys who brought you the War in Afghanistan. Not only is all that local trust gone… but it’s much easier to actually subvert the system now! Corrupting one federal election agency is loads easier than corrupting volunteer staffs at some significant fraction of 132,556 separate voting places. (And just wait until the next president you personally oppose decides to close or open some voting places in a pattern that even smells like it might be partisan.) Consolidating elections like this is a bad idea!

Fifth, and I’m not sure whether this is the weakest argument against a national popular vote or the strongest, but here it is: it will never pass. At least, not in the current small-state vs. large-state political landscape. It would transfer too much power over the presidential election from small states to large states. Those small states control enough electoral votes to prevent NPVIC—much less a constitutional amendment—from ever becoming law.29 This was a problem at the Founding and it is a problem today. You may not think it’s a legitimate problem, you may think (as some of the Founders did) that the small states just need to stop being selfish and give up their power for the greater democratic good… but they aren’t going to do that, because they are not suicidal. At Some Constitutional Amendments, we only propose an amendment if we think it could someday be politically viable. The national popular vote, even if it were a good idea, will never be viable.

We do need to abolish the Electoral College. But abolishing it in favor of a national popular vote would make all of our problems worse, not better.

Next Voyage

After this longer-than-expected survey of American presidential history, we’ve learned a lot about the various ways Americans have elected the president. Hopefully, we’ve also learned about some of the strengths of each method—and, more importantly, their failures.

Armed with this history, I have no doubt you can imagine many different alternatives to our current presidential election system. I suspect that every single one of them is better than the broken-down bus of a system we have today.

However, this is Some Constitutional Amendments, so I do have an idea of my own. Next week, I’ll pitch it to you, and you can decide what to make of it.

UPDATE: This article originally claimed that Benito Mussolini won a free and fair election, along with Hitler, but reader Sathya Rađa pointed out in the comments that that isn’t true, so I fixed it.

UPDATE 2: I apologize for the fact that there were like 12 subscription prompts in the post for a few hours today. I added one, but Substack refused to display it, so I clicked the button several more times and finally gave up and closed the laptop. Hours later, I checked back again, and boom, one zillion subscription prompts. It really broke the flow! But fixed now.

Yeah, whatever, Haley is still technically in it. I will vote for her on March 5. I am speaking from considerable expertise when I say that she has no path. In 2016, there really was a chance, and a good one, until quite late in the race, long after conventional wisdom had declared the race over. This isn’t 2016.

“chuckling myself into an early grave,” it’s the hot new phrase, all the kids are sayin’ it.

Of course, the English system itself was not yet fully developed. Today, the House of Commons directly elects the Prime Minister. In the election, they run with their candidate for PM as the face of the party, and, if they win, he gets the big chair.

In the late 18th century, the King still actually decided who to appoint as Prime Minister. However, a Prime Minister who did not enjoy the “confidence of the House” would generally be forced to resign. This “confidence” ultimately boiled down to majority support. So the House of Commons did not directly elect the P.M., but they were immensely influential in the selection process anyway. In the American system, the Electoral College has prevented the House from having anything remotely like that level of influence.

I rely here, as I so often do, on Akhil Amar’s America’s Constitution: A Biography, especially pp64-72.

Today, of course, the President of the United States is widely recognized as the single most powerful human being alive. Indeed, any given U.S. President is arguably the most powerful human being who has ever lived, except other U.S. Presidents. This only sharpens the Founders’ healthy concerns.

However, nobody called it that at the time. The phrase “electoral college” began showing up in the early 1800s, and thus does not appear in Farrand’s Records, and it is thus waaaay harder to ctrl-F for the Founders’ debates about the Electoral College than it ought to be.

Akhil Amar notes Gouverneur Morris’s disagreement on this point on p515 of Farrand’s Records, but, in context, it’s clear Morris is not expressing a majority opinion, and the other delegates continue to assume Mason is right in subsequent discussion.

In this “final election,” the House would vote by “unit rule,” a voting system used by the Confederation Congress and by the Constitutional Convention. In this system, each state’s delegation casts only one vote. So, for example, all 8 Congressmen from Minnesota would get together, talk amongst themselves, vote amongst themselves to decide who Minnesota was voting for, and then announce that vote to the House as the vote of Minnesota. (Unfortunately, Minnesota’s congressional delegation is currently split 4 D / 4 R, so what would probably happen is they would deadlock, and Minnesota would cast no vote in the House’s presidential election.)

The unit rule appears to have been a concession to the small states, who were afraid of being swamped in the House by the large states. The small states had originally wanted to throw the election to the Senate, where small states would be on equal footing with the large states, but the large states and others were very unhappy with the idea of the aristocratic Senate making final decisions about the Presidency. Some in debate worried that the Senate and President would form an aristocratic cabal, neuter the House permanently, and keep the President in office for life. They started making noises about throwing the whole thing overboard and having direct national elections anyway. The unit rule compromise salved the worries of the small states while relieving the other Founders’ concerns about aristocracy.

Today, the unit rule is almost extinct; every state party constitution I’ve ever read (for Republicans or Democrats) has a bylaw prohibiting the unit rule. (This is in no small part thanks to the McGovern-Fraser Commission of 1972, which we’ll discuss later on.) Yet the small-state unit-rule compromise remains in the actual Constitution, terrifying Democrats in every close election.

It must, again, be admitted: one of the most important differences between states, which would become the singular difference by 1820, was the South/North, slave/free distinction.

Most of the Founders expected most elections to be resolved in the House, because they thought consensus candidates would be rare… but they already knew they had a consensus candidate for the first election. Everyone assumed that the Electoral College would overwhelmingly elect George Washington the first President. This assumption was correct.

It’s hard to say exactly how broad, because only a few states had popular votes for electors, suffrage for those elections varied widely, electors were unpledged, and many of the voting records are lost to history anyway, but it seems like well over 75% of the nation supported President Washington and Vice President Adams.

Instead of appointing electors directly, Tennessee’s legislature appointed nine people, three in each district, to appoint electors. I don’t know why they did this, but I’ll bet it’s an interesting story.

There were only sixteen states. Massachusetts gets counted twice because it did a hybrid: voters voted for electors in each congressional district, and the state legislature appointed one of the top two vote-getters in each race, and also appointed two directly.

The Twelfth Amendment also failed to preserve the Founders’ vision in a different way: one of the proposed provisions for the Amendment would have required states to appoint electors by congressional district, rather than statewide. This was proposed because states and political parties were realizing, often to their dismay, that states needed to cast all their electoral votes for a single candidate, winner-take-all, in order to maximize their voices on the national stage. If Federalist states supported winner-take-all elector slates, but Democrat states supported district-by-district slates, then the Federalists would always win every election forever, even if the Democrats won 75% of the popular vote. By outlawing statewide electoral slates, the Twelfth Amendment could have preserved states’ flexibility to have their electoral votes represent the diverse views of their citizens. But it didn’t, so now every state today is winner-take-all (except Nebraska and Maine, which quirkily hold out in appointing electors by district).

This description of the caucus-convention system borrows heavily from my 2016 article, “Conventional Chaos, Part 1: The View from 10,000 Feet,” although I have modified some of my views (and learned more facts) since then.

Eisenhower defeated the conservative faction led by Robert Taft, and Lincoln defeated the conservative faction led by William Seward, which had far stronger anti-slavery views than Lincoln did at the time. Of course, the more ideological faction won its share of battles, too: Goldwater defeated the moderate Rockefeller Republicans in 1964 (and lost the general election decisively), and Reagan led the conservative faction against George H.W. Bush (and kicked off a 12-year GOP tenure in the White House).

Given the pro-voter, anti-institution vibes in the air in the 1970s, it may well be the case that something was going to burn the entire caucus-convention system to the ground regardless. So I’m not sure whether it was really George McGovern’s fault, or whether he was merely the chosen form of our destructor, a la the Stay-Puft Marshmellow Man.

A caucus is functionally a primary if there is a presidential preference poll taken the night of the caucus and if, under state party rules, the results of the preference poll must be used to select and/or bind delegates to the national, state, or district conventions.

Although district and state conventions don’t determine national outcomes, it’s obvious that, if Jimmy Carter’s campaign gets to choose (or bind) 55% of the district delegates, Jimmy Carter is going to end up with 55-100% of the national delegates, no matter how much talking there is along the way. The deliberative aspect at higher levels is largely bypassed and renders the rest of the process pretty pointless. Any binding at the precinct level turns the caucus into a functional primary.

Elaine Kamarck explains the ins and outs of the collapse of the traditional caucus-convention system in the excellent first chapter of her book, Primary Politics. I quibble with certain parts. In particular, I think Kamarck understates the importance of the McGovern Commission’s proportional representation mandates. Proportional representation locked delegates in to supporting certain presidential candidates immediately at the precinct caucus, months before the state convention, much less the national convention. Binding all or most of the delegates on caucus night bypassed all the multiple layers of deliberation and rendered the entire rest of the process pointless. So lots of states cancelled the process and switched to binding primaries!

Despite this quibble, Kamarck’s overview is really good, and it’s easy to understand how the McGovern-Fraser Commission might not have appreciated the unexpected interactions their mandates would have with other forces, which gradually pushed both parties into strongly favoring binding primaries.

The first presidential primary law was Wisconsin’s 1905 law. They held their first presidential primary election in 1908.

Oregon and North Dakota are often said to have been the “first” to establish and hold presidential primaries (in 1910 and 1912, respectively). That’s the current story on Wikipedia. By this, people seem to mean that Oregon was the first state to pass a law where voters marked their preference for President of the United States on a ballot, and tying the election of national convention delegates to that preference. That seems to be true, but seems to miss the point. Wisconsinites were bypassing the caucus-convention system with direct democratic elections years before Oregon, and that’s the essential characteristic of a primary.

Hat tip to Louise Overacker’s 1926 book, The Presidential Primary, and I thank God for the public domain and Google/Internet Archive book-scanning projects. (Although Overacker was born in 1891 and died in 1982, six years before I was conceived, this long-forgotten book remained under copyright until the Year of Our Lord 2022. Copyright is broken. Were it not for the book-scanning projects, this book could well have been lost after such a long wait in copyright limbo.)

State party delegate allocation rules are hard enough to find online for the current election cycle, much less old ones!

If it weren’t for TheGreenPapers.com, we’d all be doomed. Anything before TheGreenPapers.com launched in 1999 is basically rumor. That’s how I know Iowa had a functional primary in 2000: GreenPapers told me.

Note that the Democratic Party has always estimated how the Iowa caucus preference poll would ultimately translate into national delegate counts, even before delegate-binding began. Newspapers often reported those totals as if the caucus had bound delegates in some way, but that doesn’t mean they actually were bound.

It’s interesting to speculate how history would have played out had Santorum won the 2012 nominating contest. In retrospect, it seems clear that he had a stronger path to victory than I gave him credit for at the time. (And I was giving him more credit than most!)

The exact coalition of voters Santorum appealed to—blue-collar Obama voters—turned out in massive numbers just four years later to vote for the only Republican candidate in decades who seemed to be on their side, Donald Trump. Santorum might very easily have won using the Trump coalition four years earlier, without all of Donald Trump’s baggage. What do the late 2010s look like in that world? I don’t know. I suspect better! But a lot of people hated Rick Santorum with an all-consuming passion that only Trump has been able to make them forget, so who knows?

In 2016, Gwynn Guilford, now at the Wall Street Journal, did some reporting on the 2012 rules fight for Quartz. She even interviewed me! Go read some newspaper quotes from 2016!James!

The key thing to remember is that, when John Boehner gavels down the vote over clear and properly-ordered calls for division, what he is doing is illegal. There are better videos that more clearly show (and audibly record) the delegates calling for division, but I like how clearly this one shows Boehner’s steamroller. (Her article goes on to make the same point I’m about to make about Trump.)

People always talk about Mitt Romney like he was some noble warrior too good for our rough-and-tumble politics. That is certainly what Mitt Romney believes about himself! But his 2012 overthrow of the RNC rules to protect nothing more than his personal vanity exposed the true Mitt Romney. He’s a lying sack of poop who holds the rule of law in contempt, just like all the rest. (Same with John Boehner.) There was no “nobility” in the old establishment, no honor, no honesty. They were just better at lying about it. They deserved to be destroyed, and one of the few true joys of the Trump Darkness has been watching them be swallowed up and spat out.

On the other hand, one of the many true pains of the Trump Darkness has been finding myself routinely on the same side as Mitt Romney. Ugh.

I mostly refrained from putting links in this line because I did not want to provoke a defensive reaction from readers who have a soft spot for this or that president of the past fifty years.

But if you are wondering, “Which specific candidates is James thinking of here?” the answer is, “All of ‘em.” Both parties. All of ‘em. Yes, even him. And especially him. They don’t all fall into every category, but they do all fall into at least one.

The presidential primary system not only fails to encourage men of good character to stand for election; it actively prevents them from winning.

$5.7 billion according to OpenSecrets, with inflation adjustment to 2012 dollars from USInflationCalculator.com.

Although the Texan and the New Yorker will vote for opposite parties, and would harm one another physically if given the chance and a legal excuse, these addled partisan hacks empowered by direct election are united by one piece of common ground: they both want to gas the Jews.

Let’s, uh… let’s leave these gentlemen to their couches.

NPVIC thinks they can, because NPVIC hasn’t thought about all the ways a canny state can cheat the NPVIC.

My first, simplest idea: NPVIC relies on state election officials determining the popular vote totals for their own states and other states. So one of the state election officials from a state that opposes NPVIC could announce that the vote total for their state is 153,000 votes for Biden, and 46 million votes for Trump. NPVIC doesn’t instantly break if that happens, but it doesn’t have very good ways of dealing with it, either.

A second, more legally-secure idea: a bright red state that opposed NPVIC (many of them do, since NPVIC would crush small-state power) could exercise their power under Article II and/or constitutional creativity to simply take the Democratic candidate off the ballot, thus denying that Democrat every popular vote in the state.

Today, those kinds of shenanigans make no difference, because vote margin doesn’t matter under the Electoral College; only victory or defeat in a given state matters. Under direct national election, however, vote margin is everything, and there are a million and one ways to manipulate it. Here’s another: California would undoubtedly start letting 14-year-olds vote, driving up their legal suffrage totals and thus their voting weight in the presidential election. Texas might respond by instituting demeny voting and then encouraging Texans to have more babies. I’m pro-natalism, but this is no way to run a republic!

The only lasting solution is federal control of elections.

The one thing that I think could change this is if a Democrat lost the popular vote but won the Electoral College, enraging Republicans and turning them decisively against the College. This is more likely than you think! In a reasonably close election, there’s roughly a 10% chance of a split between the electoral vote and the popular vote. (I base this on FiveThirtyEight models from 2020, 2016, and some loose talk by Nate Silver in 2012.)

Contrary to popular belief, electoral college / popular vote splits do not naturally favor Republicans. They don’t even naturally favor small states. (Small states benefit from the electoral college because it makes candidates sometimes pay attention to them, not because it reliably allows them to win with a popular minority.) Republicans just got very, very lucky winning two splits in a single generation.

In 2012, the electoral college actually favored Obama! There was roughly a 5% chance that Obama would lose the election but win the popular vote—people called this his “Blue Wall,” which you might remember if you were around at the time. Nobody noticed how the Electoral College favored him at the time because Obama won the popular vote anyway, and very convincingly. Over the long run, the electoral college favors Republicans about half the time and Democrats about half the time.

If these figures hold up, then we should expect to see a split between the electoral college and the popular vote to occur about once every 6 or 7 presidential elections. (The probability of it happening at least once in the next 7 elections is 1-(.97 ) = 53%.)

That split should favor Democrats half the time, so Democrats have about a coin-toss chance of winning an election on a popular-vote/electoral-college split approximately once every 12 to 14 presidential elections or so. At some point between now and 2080, then, there’s at least a halfway chance of the Dems finally winning an election on a split. There’s even a decent chance (>20%) that it happens before 2044!

If it does, Katy bar the door. Direct presidential election will still be a bad idea, but I expect it would nevertheless become politically viable.

I’m assuming for this article that this will not happen in the next 20 years.

“and one guy in Maryland who voted Adams-Jefferson, just to mess with historians.” 😂 brilliant

A fairly interesting post. However, I think I have to object to this portion:

"Heck, just look across the pond at Europe right now! They’ve got even more democratic democracies than we do. How’s it working out for ‘em? Not so hot, babes! Every time France is in the news, it’s either because another riot spun out of control, or because the neo-Nazis—not the Trump GOP, which is bad enough, but the actual neo-Nazis—are at serious risk of winning a national election. Same in half-a-dozen other Western European countries. "

I assume the "actual neo-Nazis" are in reference to to the political party National Rally (previously National Front), because I can't think of what else it would be. Now, I'm not an expert on French politics. But I have done a bit of research, and I don't think this is the case. Everything that follows is my understanding of the situation, which could be flawed in some areas, but I think is correct.

So, I definitely remember how in 2017 there was a lot of fearmongering about the fact Marie Le Pen (their candidate) made it into the top 2 of the presidential election. But the claim that "actual neo-Nazis" were in danger of winning a national election (the presidency) doesn't seem quite true.

First, none of them have been at "serious risk" of winning a national election. It is true that National Rally has, on three occasions, managed to get into the "final two" of the presidential election (basically, they have an election where each party runs one candidate, everyone votes for one, and then you get the "real" election between the top two people). But National Rally got walloped each time this happened. In the one-on-one runoff election in 2002, the candidate got a measly 17.7%. The other times their candidate managed to land in the final two was 2017 and 2021, but still only got 33.9% and 41.45% respectively. With vote spreads like that, they weren't in any "serious risk" of winning.

But can National Rally be described as "actual neo-Nazis" to begin with? Apparently they were far more extreme in the past (the original founder, while not necessarily a Holocaust denier, was definitely a Holocaust skeptic), though I'm not sure if they quite rose to the level of being "actual neo-Nazis". But even if they were, of the times their candidate got into the runoff for president, that would apply only to the 2002 election. They did try to start moderating things starting in the 2010's (as part of this, the original founder got kicked out in 2015) and it was only under those circumstances--the expulsion of the extreme elements--that they managed to get into the 2017 and 2022 presidential election runoff, even if both of them ended up being pretty one-sided in favor of the opponent (though they did improve compared to where they were before).

If I look over their current positions, they don't really seem any more extreme than the "Trump GOP", and certainly are not neo-Nazis (well, maybe to those who think the Turmp GOP is a bunch of Neo-Nazis). They have managed to have more electoral success recently; in 2023 they managed to get 15% of the parliament, their best finish by a significant margin. But again, this was AFTER a concerted attempt to kick out the extreme elements of the party.

So it doesn't seem to me like there were ever "actual neo-Nazis" in danger of winning a national election (the presidency) in France. That was just the media trying to hype things up way more than they were, both by exaggerating how extreme a candidate was or their likelihood of success. Maybe National Rally has a real shot in the next presidential election in 2027, but as I noted, if they ever were neo-Nazis, they definitely aren't now.

I don't know what the other half a dozen nations you refer to are, as you only named France. But it's been my experience that when the media tries to sell you on some party or individual in Europe gaining power as being "far-right" it usually means their positions are no more extreme than that of the US Republican Party. See, for example, the Swedish Democrats or Brothers of Italy. The mainstream media spent so much time talking about how absurdly right-wing they were after they gained power by being in the majority, and then I look at their positions and don't see anything that would be out of place among the Republican Party. Maybe that means the Republican Party is far-right (people always do claim the US is more right-wing than most of Europe), but in any event these supposed far-right parties don't seem any worse than one of the dominant parties in the US.

I have some other potential comments, but they may be addressed in the next post, so I'll leave them to the side for now.