Worthy Reads: Small Apocalypses

Worthy Reads for May 2024, unless it's June by the time I publish, in which case for June 2024.

Welcome to Worthy Reads, where I share some articles and other links I think are worth your time. It has the rare De Civitate paywall. Everyone gets the first half of Worthy Reads, but only paying subscribers get the second half. Retweets are not endorsements.

“Why Don’t We Just Kill The Kid in the Omelas Hole,” by Isabel J. Kim [Fiction]:

But nobody heard the third kid’s sobbing because of the soundproofing, and also because now no one was allowed to go see the kid since security had been beefed up around the load-bearing suffering child to prevent its death and prolong its suffering. Which meant that the kid-killers had to seriously plan the next attempt, and everyone had time to decompress from the first two murders of the load-bearing suffering child, and also, the video of the second very graphic murder circulated outside of Omelas.

…What the Omelans didn’t say was that their second grievance was due to the fact that the kid killers had broken the unspoken code: if you had a problem with the load-bearing suffering child, you were supposed to get the hell out of Omelas and keep it to yourself. You weren’t supposed to kill the kid. As a teenager, you were supposed to learn the blunt truth that your society was built on a single ongoing act of senseless, meaningless cruelty, and then you were supposed to cry about it or rage about it, but either way you were supposed to get over it and grow up and get on with your fully-paid-for-by-the-state education system and your festivals and your legal weed and your drooz.

This short story is, of course, a sequel to Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic short story, “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas.” If you haven’t read the original “Omelas” before, congratulations on being one of today’s lucky 10,000, now go read it. “Omelas” is so ubiquitous it also featured (briefly) in the last edition of Worthy Reads, too, when I (briefly) mentioned the 2022 Star Trek episode that ripped it off. I will henceforth assume that you’ve read it.

The original “Omelas” is a very simple parable with a very clear message. It is particularly beloved by pro-lifers, since “Omelas” so perfectly describes our society. The irony that Le Guin herself was passionately pro-choice, and procured an illegal abortion herself in 1950, is not lost on us. We all imagine ourselves to be the ones who would leave Omelas. The truth is that most of us are not. There is no reason to imagine Le Guin herself must be exempt. Le Guin was abandoned by her boyfriend, coerced by her university, and faced immense pressures that could not have been overcome without heroic love. Anyone in her position would find Omelas beguiling. Even you.

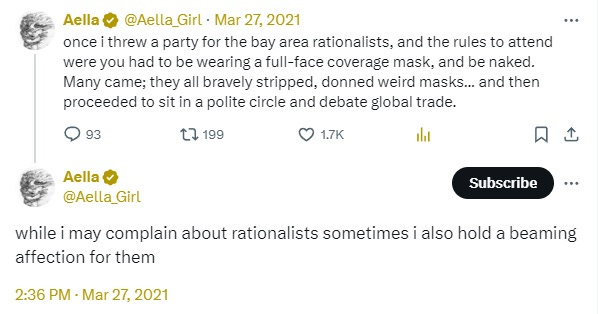

This new story, by contrast, sticks its tongue firmly in its cheek and thereby becomes a cipher. I enjoyed it for that reason. I was lurking a rationalist forum when I stumbled across “Why Don’t We Just Kill The Kid,” and the rationalists were really irritated with it. They couldn’t figure out what point it was trying to make, but they strongly suspected that—like the original “Omelas”—it was making some sally against utilitarian ethics (which are very popular in rationalist forums). Like good rationalists, they were looking for the argument: they identified the story’s presumed conclusion, extracted the missing premises from the text, and refuted the premises.

The story is good, though, because it doesn’t have premises or a conclusion. It is, at most, a sort of absurd satirical deconstruction of Omelas, and it makes fun of everyone on the way down. (My camp, The Ones Who Crap On Omelas, is not spared.) It is only barely a true work of short fiction, because the characters and choices in the story are few, perfunctory, and broadly drawn. But same with Le Guin’s original!

Biblical archaeologists oughta reread the Bible, by Lyman Stone:

The view… (shared by many scholars) is:

Around 1000 BC, a group of Canaanites congealed into a group that gradually started worshiping a pantheon whose chief god Yahweh eventually became the semi-sole God by 800-ish BC, AND that this story contradicts the Bible.

I want to offer two challenges to this narrative:

1) The evidence for Israel arising from prior Canaanite groups is nonexistent. It just isn't there. Wyman can't cite any of the kinds of evidence (esp. archaeogenetics) he usually cites for that kind of claim….

2) With a very small modification re: migration, the story offered by the Bible isn't contradicted.

Stone points out, over the course of about a hundred tweets well worth reading, that the Bible itself describes the Israelites as a complete hot mess, a weak power at the best of times, intensely tribal, riven by internal divisions, relatively poor even at its height, and completely incapable of firmly establishing the cult of Yahweh even throughout its own territory, much less anywhere else.

This is both:

incredibly obvious if you’ve read the Bible, or even the CliffNotes of the Bible, and

completely overshadowed by our actual cultural beliefs about the Bible, where we imagine King David as a mythic conquerer alongside Caesar and Alexander (instead of what the Bible depicts: a mildly successful tribal warlord who wasn’t even on the same gameboard as Caesar). We picture King Solomon with his legendary treasure hoard, wealthier than Midas, his temple a lost Wonder of the World (when actually the Bible presents him as merely the first Jewish leader wealthy enough to afford… some decent wood).

These legends play a bigger role in our cultural reception of the Old Testament than the text of the Old Testament itself. When archaeology confirms the text but refutes the legend, we are prone to misinterpreting it as archaeology “disproving” the Bible.1

But it doesn’t. Popular biblical archaeology largely confirms the Bible, but hasn’t noticed yet.

As a bonus, Stone’s whole thread is a commentary on two episodes of The Tides of History, a podcast by Patrick Wyman. I never got into The Tides of History, but I adored Wyman’s The Fall of Rome, which really taught me most of what I know about Roman history after Trajan.

(Yes, ladies, I think about the Roman Empire at least weekly, most recently yesterday at about 10:00 in the morning.)

“Tyranny and Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church: A Jesuit Tragedy,” by Dr. John R.T. Lamont:

Restoration of discipline among clergy and religious was one of the main goals of the Counter-Reformation. The theories of law and authority that guided this restoration differed from a pure nominalist position, but these differences were lost when the practical principles for training in obedience were devised. These principles embodied a tyrannical understanding of authority, and a servile understanding of rightful obedience as consisting in total submission to the will of the superior. The most influential formulation of these principles was given in the writings of St. Ignatius Loyola on obedience:

…The third and highest degree of obedience consists in conforming not only one’s will but one’s intellect to the order of the superior, so that one not only wills that an order should have been given, but actually believes that the order was the right order to give, simply because the superior gave it… In the highest and most meritorious degree of obedience, the follower has no more will of his own in obeying than an inanimate object.

…This approach to authority had damaging effects on clergy and religious. The exaction of servile obedience from subordinates destroyed strength of character and the capacity for independent thought. Exercise of tyrannical authority by superiors produced overweening pride and incapacity for self-criticism. The fact that superiors all started off in a subordinate position meant that advancement was facilitated for those proficient in the arts of the slave — flattery, dissimulation, and manipulation.

The laity could not hope for advancement in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, so the effect of promotion of a servile understanding of religious obedience was to infantilize them in the religious sphere. This infantilization can be observed in religious art and devotion, especially from the 19th century onwards, and in willingness to give blind obedience to the clergy.

The Catholic sex abuse crisis is a profound crisis with many, many causes. I wrote about the crisis at Commonweal some years ago, and I remain convinced of what I wrote then.

However, Dr. John Lamont noticed that a defective theory of obedience contributed to the crisis (and many other problems in the Church today), and I have seen literally no one else make this point. This insight has shaped my understanding of the Scandal for years. It’s hard to summarize the argument in even a long excerpt, so I encourage you to read the whole thing, but he digs back into history and shows that, after the nominalist revolution and the lionization of the Jesuits, a perverse notion of obedience became normal in the Catholic Church.

This phenomenon, in just the way Lamont describes it, is just obviously present everywhere in the Church today, not to mention in the Church of a century ago. I defy you to read the seminarian testaments published at De Civitate in 2019 and not see this defective model of obedience at work. (I can assure you that I know more stories that could not be published, and have heard far more rumors than those, which tend to confirm this view is common, though not always so ugly.) Nor is it only in the seminaries; I know good men, good dads, who believe that servile obedience is a virtue, even though (Deo gratias) they don’t actually live it out.

I think that we will never beat the abuse crisis until this notion of obedience is beaten, too.

Alas, Lamont’s original article is slowly vanishing from the Internet: the link above is to an Internet Archive version of a reprint (because the original is gone and the reprint server is 503’ing). I dimly recall the article was originally published in two parts, but this version seems (?) to have both parts. I’m tempted to look up the Lamont guy—I’m sure we have mutuals—and confirm that I have the whole thing.

UPDATE 28 May: Turns out we do have mutuals! This was the complete original article, but Lamont later developed the ideas into a somewhat longer essay called “The Catholic Church and the Rule of Law,” which was published online in two parts: Part I (mirror), Part II (mirror). It begins with this striking thesis: “[T]he rule of law does not exist in the Catholic Church.”

This later essay covers a lot of the same ground, but in greater detail, with more useful digressions. (I had quite forgotten that some of my key ideas about the strict limits papal infallibility had come from an aside in this essay.) Therefore, if I were only going to read one of the two articles, I would read “The Catholic Church and the Rule of Law” instead of “Tyranny and Sexual Abuse: A Jesuit Tragedy.” However, “Jesuit Tragedy” has much better formatting, so, trade-offs.

Runner-Up Video of the Month: The “Song of Durin” by Clamavi de Profundis:

Clamavi de Profundis is a choral group that wrote (quite pleasing) music for (many) of the songs J.R.R. Tolkien wrote in The Lord of the Rings. I’m reading LotR to my nine-year-old and have taken to flipping ahead, checking if there’s a song imminent, looking for a CdP version of the song, and memorizing the tune for when we hit the song.

Yes, I sing the songs in The Lord of the Rings. Anti-Peter Jackson people are always telling me LotR is all about the poems and songs and so forth, not the action, so why not go all-out with them?

(You can’t just use Clamavi de Profundis, though. They’re great with the dwarves, but IMO hit-and-miss with elvish songs. Like, all else aside, what in the name of sanity does their intro to Namárië think it’s doing? Compare Tolkien’s version, which is just Latin chant because holy cow was that man ever Catholic. When reading to your children, consider memorizing Adele McAllister’s melodies for Namárië and other elvish songs. That said? If it’s a dwarvish song, I don’t even look at anything else. It’s gonna be CdP. They also do Chesterton and I am just now noticing that they dedicated that song to “Our Lady of the Holy Rosary,” so definitely check that out.)

Below the paywall: a key insight into our military recruitment shortfalls, teaching the grace of apocalypse, and Israel’s impossible diplomatic position. Also the actual video of the month and a bonus Retro Short Review of Tasmyn Muir’s Gideon the Ninth!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to De Civitate to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.