Progressives Seem Confused about the Supreme Court

Trying to have their cake and call it undemocratic, too.

Editor’s Note: I’m sorry everything I’m writing this week seems to be about abortion law, but… what else could I be talking about this week? Omicron is boring.

Stephen Colbert last night observed that Roe/Casey is likely to be overturned, then complained:

Well, I don’t want to get too technical, but… what’s the word… we don’t live in a democracy. Five of the nine justices were appointed by presidents who lost the popular vote; the last three confirmed by a Republican Senate who now represent 41 million fewer Americans than the Democrats. In fact, Republican senators haven’t represented a majority of the U.S. population since 1996. A lot has changed since 1996. Back then, the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor went to Kevin Spacey—and the Best Director was Mel Gibson.

Alright, let’s carry this line of thinking through to the end. Suppose Americans were allowed to vote directly on abortion policy, via referendum. Would they come up with Roe v. Wade or Planned Parenthood v. Casey? No, not even close. The Mississippi law at issue in Dobbs v. Jackson (which bans abortion after 15 weeks) directly violates Roe/Casey… but it’s supported by 53% of those who offered an opinion in a poll of nationwide adults, and certainly has much stronger democratic support in Mississippi itself. (Note that likely voters are consistently even more pro-life than “adults” as a whole.) This is consistent with a generation of polling showing strong support for second-trimester, pre-viability abortion bans, and even surprisingly robust support for heartbeat laws (although heartbeats laws don’t yet have nationwide plurality support).1

That’s exactly why the state of Mississippi and the pro-life movement are using Dobbs to demand that the Supreme Court return abortion law to the ordinary democratic process. The pro-democracy side in Dobbs is the anti-abortion side.

Colbert is right that three justices on the Supreme Court were appointed by Presidents who lost the popular vote for President. (Colbert says five justices, but he’s mistaken.2) The Supreme Court is, of course, by design, an undemocratic institution. That is why originalist-textualism has to work so hard to restrain the judiciary from usurping the powers of actual democratic institutions. What the Court did in Roe and (even more explicitly) in Casey is a perfect example of that usurpation. If you support democratic control of abortion policy,3 then you side with Mississippi and its democratically-popular, democratically-passed law.

Colbert never acknowledges that he’s against democracy here. I don’t think this is out of malice. I don’t even think it’s because it would ruin his argument. (Although it is pretty funny that his argument boils down to, “I think the problem with an inherently undemocratic institution supporting democratic decision-making is that it didn’t come to that decision democratically enough.”) I think Colbert is genuinely incapable of recognizing that he’s opposed to democracy here. He just assumes that whatever policies seem fundamentally important to him are “democratic” and other policies—even those supported by clear majorities of the demos—are somehow not “democratic.”

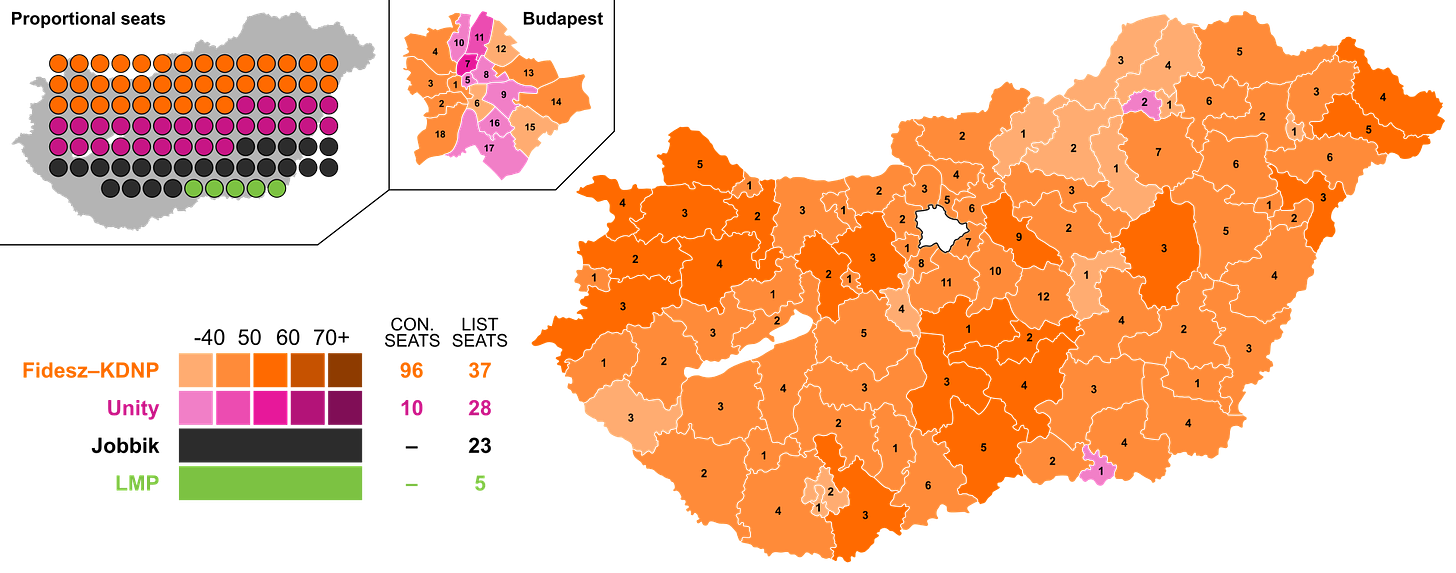

Yesterday, I drew an analogy between Dobbs and Brexit, where some center-leftists seemed to be having trouble processing the evidence about what was likely to happen because they simply couldn’t fit the possibility into their worldviews. Today, a new analogy: left-wing professed support for an undemocratic outcome in Dobbs (all in the name of “democracy”) reminds me of left-wing opposition to the government of Viktor Orbán in Hungary; they keep calling him an “autocrat” who is a “threat to democracy,” even though Orbán’s very peculiar flavor of “autocracy” involves him winning free and fair elections in every voting district in his nation and then using his democratically-elected supermajorities to implement exactly the policies he campaigned on. (See also Poland’s Law-and-Justice party.)

Stephen Colbert’s confusion is certainly not limited to Stephen Colbert. That’s the only reason I bring it up; there’s no reason or even excuse to give the kowtowing, downward-punching Colbert attention otherwise. (The only late night host who remembers what he’s doing out there is Jimmy Fallon, and I’m sorry he had the bad luck to take over Johnny Carson’s desk just as the Trump years were heating up.) You can see this deep conviction that Roe v. Wade is somehow democratic everywhere on the Left right now. It’s weird, but, because of the way our media influences mainstream thought, you can’t see it at all… until, suddenly it clicks, and then you see it all the time.

This is also not the only line of confusion I’ve noticed on the Left this week. A different school of thought on Dobbs v. Jackson recognizes the judiciary as fundamentally undemocratic… and so rejects the legitimacy of the judiciary altogether. Ryan Cooper wrote a piece last year calling on Democrats to simply ignore the Supreme Court from now on, at least whenever the Court made decisions the Democrats didn’t agree with. This piece got re-upped after the Dobbs oral arguments and I was surprised to see one or two of my left-wing Facebook friends echoing its arguments.

Now, I’ve questioned judicial supremacy plenty of times. I, too, used to oppose judicial review entirely. I changed my mind in Spring 2010 when I took a class on the Civil War and the Constitution with Michael Stokes Paulsen—a class that was the closest thing I’ve ever had to a conversion experience—but I still came out of it firmly committed to departmentalism, the view that each branch of government is the final arbiter of constitutional meaning within its own sphere. (In effect, this still leaves the Supreme Court with a lot of power, but not an absolute power to rewrite laws as they see fit; see, for example, Justice Gorsuch’s dissent in Barr v. Amer. Assoc. of Political Consultants.) I am, in short, not entirely deaf to Mr. Cooper’s argument.

But, again, consider what this argument would mean for Roe/Casey. Both were, putatively, exercises of judicial review. They struck down democratically passed laws. If you are so mad about the Supreme Court’s likely decision in the near future to junk Roe/Casey that you simply ignore the judiciary altogether (as Cooper and my Facebook friends are inclined to do)… then Roe/Casey, in effect, go away anyway. States will just pass laws like Mississippi’s, regulating or banning abortion according to the will of their voters’ elected representatives, and it will be exactly the same as if the Left had just accepted the Court’s ruling in the first place. Of course, it’s possible that the federal government could pass a federal law mandating abortion rights everywhere, but states would simply contend that the federal government has no power to pass that law, they’d ignore it, and uh-oh.

Another favorite solution on the Left is to pack the Supreme Court with left-wing justices. Congress has the power to increase the number of Supreme Court justices at any time (reducing the number is harder, because sitting justices must be allowed to serve for life), so the idea here is simple: the current Court has a 6-3 conservative majority. Add 4 justices, maybe 5 to be safe, have Biden nominate and confirm them all, and now the Court has an 8-6 progressive majority that can uphold Roe v. Wade and reverse Citizens United and so forth! But this, too, is a double-edged sword. Unless Democrats believe Republicans will never hold a trifecta again (babe, both parties get a trifecta about once a decade under our current polarization, and adding D.C. as a state isn’t going to prevent that4), Republicans will respond next time they’re in power by adding 4 or 5 conservative justices, who will re-reverse Roe/Casey, and ‘round and ‘round we’ll go. As a practical matter, this solution (in the long run) is identical to simply ignoring the Supreme Court as Ryan Cooper suggests, because nothing the Court says will ever matter for more than a few years. Once again, Mississippi is gonna get its 15-week abortion law in place, no sweat.

The weirdest arguments I’ve seen are from people who combine one of these lines of argument with anti-originalist, legal-realist arguments that the Constitution’s meaning is whatever the justices want it to be. For example (based on, but not direct quotes from, real conversations I’ve had/seen this week):

Progressive: “The Supreme Court must uphold abortion as a fundamental right.”

Me: “But the Constitution provides neither an explicit nor implicit right to abortion. It’s absurd to suggest it is a fundamental right the Constitution protects.”

Progressive: “The Constitution is whatever five justices say it is. They can sustain this right if they want.”

Me: “If that were true, and the justices were no longer bound by the rule of law but rather could decree whatever they wanted… then don’t you think 5 or 6 justices on the Supreme Court, all of whom seem to be personally pro-life, would simply announce that abortion is unconstitutional and ban abortion everywhere in the nation? Honestly, they’ve got a better textual argument for that than the pro-choicers have for Roe/Casey, and you’ve just told me text doesn’t even matter.”

Progressive: “The states could simply ignore the Court’s ruling. Judicial review isn’t in the Constitution, either! ‘Justice Roberts has made him decision; now let him enforce it!’”

Me: “Okay, so is the Constitution whatever the Supreme Court says or not? Because if everyone can ignore the Supreme Court, it doesn’t actually have any say in the Constitution.”

Progressive: “Minoritarian rule must end!”

Me: “But I didn’t say anything about—”

Progressive: “What you refuse to understand is that Republicans are a threat to democracy!”

Me: “Yes, okay, fair, but you don’t seem to be particularly interested in democ—”

Progressive has left the chat.

If I may speculate on the psychology of my friends on the other side for a minute: I think what we’re seeing here, across all these confused arguments, is a cognitive dissonance hangover.

For an unbroken span of 78 years, from the day West Coast Hotel v. Parrish was handed down to the day Obergefell v. Hodges was decided, the Supreme Court of the United States was pretty reliably two things:

A strong supporter of preferred progressive policy outcomes, including some really genuinely good outcomes (Brown v. Board, Brandenburg v. Ohio, Loving v. Virginia, etc.).

Wildly anti-democratic and unconstrained by any limiting principle whatsoever, even the text of the Constitution.

In other words, for 78 years (less so for the final 15 years, but not much less), the Supreme Court acted more or less like a nine-member autocracy. It genuinely did decide what the laws ought to be, then constructed or hand-waved a legal rationale that justified its conclusions. A meekly compliant political system submitted itself to those conclusions (including the Court’s own conclusion that the Court’s decisions were final), which were binding across the land. This flatly tyrannical system of government established much of what progressives love about modern America.

But another thing progressives love about America, really a lot, is democracy and the popular vote. This has become especially true in recent years, as progressives have faced growing, asymmetrical structural hurdles to the popular will in elections for President, Senate, and House—but progressives have always prided themselves on being the “party of the people,” to an extent that conservatism, by mood, never really has.

This obviously created some difficulties. If you are a big lover of the “popular will”, some cognitive dissonance must arise when you abolish hundreds of democratically-passed, popular laws by fiat of nine old white guys in dark robes. That’s true whether your cause is bad (abolishing popular, life-saving abortion restrictions in Roe) or undeniably good (abolishing popular, but entirely evil, anti-miscegenation laws in Loving). In order to cope with the cognitive dissonance, you need to develop ways of thinking about the situation that avoid triggering it.

The progressive movement developed several doctrines that, whatever their intellectual merits, helped with the cognitive dissonance issue. One was the legal realist movement, which argued that there’s no such thing as the rule of law (only good public policy), so all judges are inherently politicians, and their job is (like other politicians) to impose their preferred policies. This movement turned the courts into a kind of super-legislature, in the minds of many leftists.

Another key dissonance-defusing doctrine: progressives internalized the idea that the anti-democratic Supreme Court was actually a cornerstone of democratic institutions, because only an anti-democratic institution could protect unpopular rights against the “tyranny of the majority.” This is true (which is why the Founders didn’t create a democracy at all). However, 20th-century progressives stopped believing that the “unpopular rights” the Supreme Court exists to protect are the unpopular rights enumerated by the Constitution. (Indeed, some enumerated rights, like the entire Second Amendment and large chunks of the First, were effectively read out of the Constitution by their view.) Instead, progressives came to believe that the Supreme Court existed to protect a list of “unpopular rights” that were just whatever policies progressives happened to like, from unregulated sex acts to school finance, recast as “rights.” This view of the Constitution is the entire basis of Heidi Schreck’s very popular one-woman show, “What the Constitution Means To Me,” which premiered on Broadway, is now on national tour, and is available free on Amazon Prime. It’s worth watching, simply to see infinite cognitive dissonance on display: to Ms. Schreck’s dissonant way of thinking, most of the reason to keep the Constitution, the very heart of democracy, is the undemocratic system where the Supreme Court hands down progressive policy victories without the possibility of veto.

These perspectives about the Supreme Court worked for 78 years. They allowed progressives to think of themselves as champions of the People, while also supporting the Supreme Court as a (tyrannical) “backstop” for when the People occasionally “got it wrong.”

But then, after a concerted 45-year effort, plus a strange 5-year transition period of growing conservative power, conservatives took full control of the Supreme Court in the fall of 2020, when Justice Amy Coney Barrett was confirmed.

Under conservative control of the Supreme Court, none of the progressive ways of rationalizing the Court make sense anymore. They still expect it to provide major political victories for outcomes the Left can’t achieve through the political process, because that “backstop” has become an essential part of how the Left understands the American system of government. But it isn’t going to do that anymore, both because the Court no longer supports those outcomes and because the Supreme Court has become self-consciously less autocratic and more democratic. (Increasing democratic accountability through Constitutional mechanisms is the fundamental purpose of originalist-textualism, which developed as a principled alternative to left-wing legal realism.)

At a party last year, I off-handedly mentioned a recent Supreme Court decision in order to make a non-political joke. A left-leaning friend of mine said, ruefully, “Man, the Supreme Court. Remember when we didn’t have to worry about them all the time?” It took him a moment—and a long, wry stare from me—to realize that conservatives have been worrying about the Supreme Court every day since long before either one of us was born, and that the Supreme Court has been the chief political concern of my entire life. It had simply not occurred to him.

For him, the Supreme Court once had a place in the American political constellation, a place that long predated his birth. Like a distant God, it oversaw democracy from on high, only occasionally giving a gentle nudge in the “right” direction. Now it’s like the stars have all crashed. Who’s going to be the backstop now? What if the Supreme Court now serves as a backstop for—gasp—the other side’s preferred policy outcomes? (Is anything else even possible, for someone who believes in the legal realist view?) What undemocratic institution will protect democracy from “bad” democratic outcomes now? Can I blame my left-wing friends for feeling disoriented?

The result is that we get all these conflicting arguments about the Court: the Court is being undemocratic because it is restoring democracy to abortion policy. The Court has infinite power, but can be ignored when it is wrong, because it has no power. The Court is illegitimate, because Mitch McConnell’s Senate Republicans and President Trump used their constitutional powers to… confirm justices they thought would do a good job and reject nominees they thought would do a bad job. And so on.

In this article, I’ve talked specifically about how the Left’s cognitive dissonance about democracy is confusing their response to the very democratic possibility that Roe/Casey will be overturned, because that’s the topic du jour and also I’m obsessed with it. But you can see the same thing on all kinds of issues. For example, ask a left-winger about the Supreme Court’s decision to leave the democratic process of redistricting in the hands of democracy (which allows partisan gerrymandering under the democratically-set rules of most states) because the democratic process has never formally assigned the Supreme Court the power to police gerrymandering. Very often, this pro-democratic decision is portrayed as a threat to “democracy” which must be corrected by some anti-democratic authority that loves “democracy” more than democracy—but what? (Most frequently, a packed Supreme Court with a fresh progressive majority, though I’m starting to see arguments that the “Republican form of government” clause can be enforced by unilateral executive military action.)

Of course, I am psychologizing about my political opponents. This is a very dangerous activity, both because it is often mistaken (mind-reading is hard) and because it has a tendency to make one arrogant and unwilling to listen to the other side. All my psychologizing may be wrong. Even if it is right, a psychological explanation for why someone offers a specific argument is not a refutation of that argument. We still have to listen to the Left’s legal arguments and engage with them on their own terms. Some of my friends on the Left are even managing to avoid these pitfalls and simply making straightforward (if absurd) arguments that abortion is actually a genuine right grounded in the text of the Constitution. But perhaps thinking about how this all must feel from the left-wing perspective will help us respond to some of their more baffling pro-Roe arguments over the next few months.

I close with a warning:

The conservative movement never developed any of this cognitive dissonance, because the conservative movement spent this entire 78-year period fighting both the Supreme Court’s arbitrary exercise of power and the idea that the will of the people is best expressed through unmediated democracy. Conservatives are far more comfortable dropping phrases like “black-robed tyrants” than progressives, because we have never viewed them as a priestly caste. When conservatives were developing originalist-textualism as a response to left-wing legal realism, the idea that conservatives might actually someday be able to wield autocratic “legal realism” power in the courts themselves was so outlandish that the possibility wasn’t even mooted.

However, now that conservatives are becoming more populist, and have taken control of the judiciary for at least the time being, we must be careful not to fall into this trap ourselves. The Court will never be a bastion of populism, and must always protect unpopular rights against democratic inclinations. At the same time, we must take care that the unpopular rights it protects are the ones we have actually assigned through the democratic process of constitutional amendment, not rights we made up out of thin air (or even rights firmly grounded in natural-law theory but unratified by our Constitution) simply because our policy goals demand it.

Fortunately, we have mostly installed textualists who are genuinely committed to a principle of self-restraint, which helps, but I worry sometimes when I read Justice Alito fulminating about one thing or another, and far more when I see Sen. Hawley raging against Bostock on the Senate floor (in the name of populism!) because textualism didn’t deliver him his desired policy win.

But if clear majorities of Americans support abortion restrictions that directly violate Roe/Casey, how do we explain polls — like the one Colbert points to — that show overwhelming support for Roe v. Wade?

Simple: the vast majority of Americans do not have the slightest idea what Roe v. Wade actually held, and have even less idea that Casey is actually the law of the land right now. Four out of ten Americans in 2013 reported that they did not know Roe v. Wade was about abortion; 7% thought it was a school desegregation decision, 5% a death penalty case; 5% called it an environmental protection decision, and 20% forthrightly admitted they had no idea. Young people and Democrats were the two groups least likely to know Roe was about abortion (fewer than half of young people knew this), so their influence has likely grown.

Polls asking Americans what specifically Roe actually held about abortion are even more dismal. (I can’t dig up my citation for this, but I assume it at least sounds pretty plausible, given the poll I just described.)

Roe isn’t popular; Roe is unknown.

Justices Alito and Roberts were appointed by President G.W. Bush in 2005. That was during President Dubya’s second term of office, which Bush won with a popular vote total of 51-48.

Note how carefully I’m avoiding committing myself to the proposition that I support democratic control over abortion policy.

Critics of Republican “minoritarian rule” often make the point that the Republicans have won two recent presidential elections despite losing the popular vote—in one case incredibly narrowly—that Republican senators have not as a whole represented a majority of the U.S. population in quite a long while, and that Republicans enjoy structural advantages in the House that make it easier for them to win. All fair critiques, especially if you believe both houses of Congress and the presidency ought to be democratic! (I do not.) But what these critics rarely note is that Republican structural advantages in the House are rarely decisive. Republicans have controlled the House—the most populist, responsive directly-elected part of our federal government—for most of the past 30 years because they have won the national popular vote in most of the elections for the past 30 years.

Republican popular wins: 1994, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2010, 2014, 2016. Popular losses where Democrats got control: 2006, 2008, 2018, 2020. Popular losses where Republicans retained control anyway: 1996, 2012. My point is not that those popular-losses-where-Republicans-retained-control-anyway are fine; my point is that Republicans are quite capable of winning popular elections, and often do!

When the Left talks democracy, replace the word with something similar to what you and Mike appear to mean by "republiquely."

This is the way that comparative political scientists, both in the United States and abroad, use the term "democracy." At least in my social circles, this is the commonsensical meaning of the word too. It refers to a system of government in which representatives are elected through votes, and judges and bureaucrats appointed by those leaders safeguard fundamental rights and execute policy.

American right wingers, and nobody else in my experience, seem to use democracy to mean direct democracy, or rule by simple majority, and then like to correct everyone else who refers to the United States or other modern democracies as democracies. No, we are a republic! In this, they manage to be both pedantic and wrong, like someone correcting your already proper use of their/they're/there.

A core feature of functioning democracy is its compulsion of differing interest groups to reach compromise, rather than a majority simply performing its will. American democracy has systems for this, but they don't work anymore, and arguably never did work particularly well. Look at the behavior of elected authoritarians like Orban, Erdogan, and Putin, and you'll see their breaking of such systems as a fundamental component of what political scientists (and not just lefties) are calling anti-democratic.

In this language, courts are absolutely a democratic institution, and they only cease to be so when a faction is able to install partisans in gross disproportion to their voting bloc, or who will reliably protect the rights of some over others. A 6/3 Supreme Court appointed and approved through a minority of voters meets these criteria as clearly as anything could. (And if our democracy were functioning properly, we wouldn't refer to our Justices as belonging to a side to begin with.)

There's a slippage, of course, since the further away people are from academic discourse, the more likely they might use the term in a loosey-goosey way where it sometimes refers to a democratic system of government and other times it means "I'm mad that my majority can't do anything." However, in the kinds of articles you're linking to, the authors appear to be using the word in the sense of the last century of comparative political science.

Rhetorically, the American right-wing language of "we are not a democracy" serves to numb any charges against practices that are openly inimical to representative government. Because Republicans have chosen to advance the interests of a numeric minority, they have increasingly needed to rely on electoral strategies that lead to power without having the support or approval of most citizens. Voter suppression tactics have become a core part of strategy, and American Republicans have become staunch defenders of systems that give them disproportionate representation, but which don't make sense to much anybody else on the planet. How much of this language about "confusion" regarding democracy is about justifying systems that give you disproportionate power?

Instead of “democratically popular and democratically passed” laws how does one sign up for “republiquely popular and republiquely passed” laws? (IYKYK)

Also, at the beginning of the piece you claim “The Supreme Court is, of course, by design, an undemocratic institution.” But then by the end are positing “But it isn’t going to do that anymore, both because the Court no longer supports those outcomes and because the Supreme Court has become self-consciously less autocratic and more democratic.”

So which is it? Speaking as a lefty who has been wholly won over by the many descriptions of textualism I’ve read here at DeCiv, are we sliding closer to or farther from democracy in our Supreme Court?