An Officer and a Gentleman (and a President)

Daily Disqualification Update (29 Oct): Trump's Strongest Argument

Disqualification Week Continues! Remember to use the Orientation post to find links to the case and the Roundup post to find other articles in this series. If you find yourself hankering for more #DQ #content, check out the pretty amazing U of Minnesota symposium on the topic, featuring pretty much everyone of note in this debate, now available on YouTube.

I know I post Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment all the time, but today we’re looking at a different portion of it than before:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

As I have previously laid out, President Trump “engaged in insurrection” against “the Constitution of the United States” on January 6, 2021. However, the Fourteenth Amendment does not disqualify every insurrectionist from office! You are only disqualified for insurrection if your insurrection also made you an oath-breaker, specifically as “a member of Congress,” an “officer of the United States,” or a state official.1

The President is not a member of Congress or a state official. That means there’s only one part of this section that could apply to Donald Trump:2 is the President an “officer of the United States”?

If he is, then Trump is disqualified, because he engaged in insurrectdion.

However, if the President is not an officer of the United States, then Trump is not disqualified.

Indeed, if the President is not an officer of the United States, future President Rachel Maddow3 could personally declare on national TV the new People’s Republic of America, raise a 50,000-man army, lay siege to the District of Columbia, personally charge into the House waving a rebel flag and wielding a machine gun, kill half the Republican caucus, be put down by federal troops, jailed, removed from office under the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, and sentenced4 to death… but Maddow could still run for President from inside the deathhouse, because she would not be disqualified for insurrection! If the President is not an officer of the United States, then the President can never be disqualified for insurrection, no matter how clear.

This is therefore a crucial question. In fact, I believe this is the strongest argument in Team Trump’s arsenal. If the Minnesota Disqualification Suit fails (~65% likelihood), my bet (~40% likelihood) is that it fails here.

When I explained the issue to my father, however, he scratched his head. “What?” he said. “He’s the president. It’s an office. It’s in the Constitution. How could he not be an officer of the United States?”

My father’s intuition is pretty reasonable. According to John Bouvier’s A Law Dictionary5 (1860), an “officer” is:

He who is lawfully invested with an office.

Officers may be classed into: 1. Executive; as the president of the United States…

There is no doubt whatsoever that the Presidency of the United States is an “office.” It would be very hard to contest it! The Constitution refers to the Presidency as an “office” no less than 26 times,6 most clearly right at the beginning of Article II, which defines the presidency:

The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.

He shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years, and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows:…

The Presidency is an office, and the President is “he who is lawfully invested with” that office. The president is, therefore, an officer established by the Constitution of the United States! How could he not be an “officer of the United States”?

The Constitutional Texts

Although everyone agrees the President is an “officer,” none of the twenty-six passages I’ve cited so far use the exact phrase “officer of the United States.” Besides the Fourteenth Amendment itself, there are only four passages that use that exact phrase. Here’s the first, the Appointments Clause:

[The President] shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

That’s an odd list!

This passage reads like a list of “all Officers of the United States.” Yet the President is not an ambassador. He is not a “public Minister or consul.” He is not a “Judge of the Supreme Court.” His “Appointment” is not “herein otherwise provided for,” because he isn’t “appointed” at all; the President is elected by the presidential electors.

One way to read this passage is to say that the President is an “Officer of the United States,” but that he is left out here because his election / appointment is provided for above (in fact, immediately before this section passage), and we should just infer that the Founders meant “all other Officers of the United States, except the President and Vice President, because we obviously just covered them.”

However, another plausible way to read the passage, one that doesn’t require us to re-engineer the text, is that this is the full list of “officers of the United States.” The President, then, is an officer, but not “of the United States.”

Here’s another reference:

[The President] shall Commission all the Officers of the United States.

That’s even odder. The President doesn’t commission himself! Once again, we could read this with an implicit, “except himself, obviously.” Yet the plainer reading seems to be that the President is not an officer of the United States. Another:

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

One plausible way to read this is that “civil Officers of the United States” is just a catch-all that includes the first two items. It should be interpreted as, “The President, the Vice President, and all other civil Officers of the United States…”

But another plausible way to read this is that “civil Officers of the United States” is a separate category that excludes the first two items. It should be interpreted as, “The President and the Vice President, plus the civil Officers of the United States…”

This passage also adds a new adjective: “civil.” Is a “civil officer” different from “Officers of the United States” in general? (As opposed to what? Military officers? Ecclesiastical officers? Foreign officers?) Do other passages referring to “officers of the United States” implicitly mean civil officers only, or not?

Forget it for now. We’ve got one more reference to the phrase, from Article VI, the Oaths Clause:

The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.

As the Trump petition observes, the President of the United States has his own Oath of Office, which is spelled out in Article II. He doesn’t take the same Article VI oath as other executive and judicial office-holders! If all “executive officers… of the United States” are bound to take the Article VI oath, and the President doesn’t take that oath, how can the President be an “executive officer… of the United States”?

To Team Trump, in their brief, this is dispositive evidence, and clearly establishes the definition of “officers of the United States”:

In short, the Constitution uses the words “officer of the United States” as a term of art referring to non-elected functionaries who exercise governmental power. This excludes the President.

However, their case gets better!

The Historical Record

Seth Barrett Tillman, sometimes with his collaborator Josh Blackman, has devoted his career to rewriting conventional wisdom about what “officer of the United States” means. Unlike most combatants in this arena, Tillman has been working on this since long before the Trump Era. He wrote his first paper dealing with the meaning of “Officer of the United States” in 2007, when George W. Bush was president, JibJab was still the king7 of online political comedy, and I was in high school. Whatever we want to say about Tillman, he alone among us cannot be accused of developing his legal theory based on his feelings about Trump.

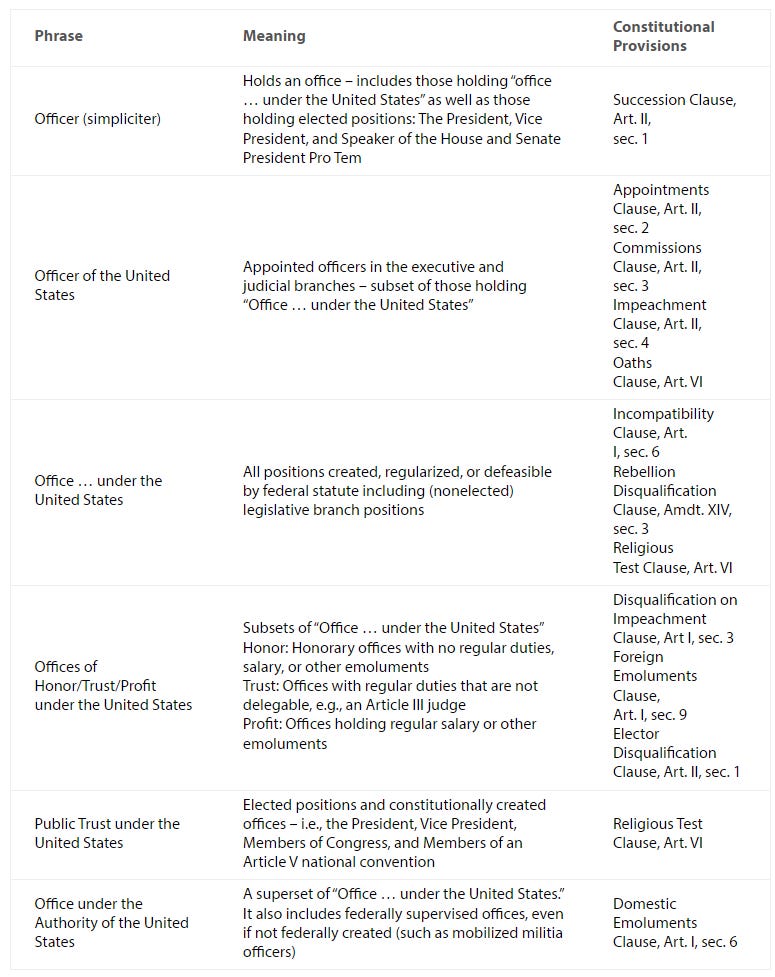

Tillman, leveraging his legal contacts throughout the British Commonwealth, has developed a framework to fit the Constitution’s language together with itself and with the English legal tradition. Even William Baude, who sharply criticized Tillman’s theory with respect to Section Three in the Baude-Paulsen paper on insurrection, has effusively praised Tillman’s scholarship and framework for understanding the term “officer,” though without actually endorsing it. It is from Baude (and Margo Uhrman) that I borrow this chart describing Tillman’s framework:

(This chart is available to screenreaders in plain text in this footnote:8 )

You can spend much of your life reading the evidence Tillman has assembled in support of this framework. Since the 2021 insurrection at the Capitol, Tillman has gone supercharged. He (with co-author Blackman) is now on Part IV of a planned ten-part series on Offices and Officers of the Constitution that makes me tired just looking at it. (That is a compliment.)

Graciously, however, Tillman summarized the parts of his argument most relevant to the Disqualification Clause in two papers: Is the President an 'Officer of the United States' for Purposes of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment? (December 2021) and a rebuttal to Baude-Paulsen called Sweeping and Forcing the President into Section Three (19 September 2023)9. If you read both back-to-back, as I did, you will fall asleep twice gain legal superpowers. Team Trump derives its whole argument about “officers of the United States” (and much else) from these two papers.

Tillman’s position is strictly a minority view. One may even call it Tillman’s “crusade” against “most sophisticated scholars,” as Baude did (in praising it!). Nonetheless, the meaning of the law is not determined by the current passing consensus of “sophisticated scholars.” It is determined by the text, by the original public meaning with which that text is fixed, and by the evidence one presents to bring forth that original public meaning. Let us, then, examine Tillman’s evidence.

First, there’s the Constitution’s drafting history. For example, the “first draft” of the Impeachment Clause said:

He [the President] shall be removed from his office on impeachment by the House of Representatives, and conviction in the supreme Court, of treason, bribery, or corruption… The Vice President and other civil Officers of the United States shall be removed from Office on impeachment and conviction as aforesaid.”

[emphasis added]

The Constitutional Convention’s next (and final) draft read:

The president, vice-president, and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.

[emphasis added]

See? The convention changed “other” civil officers to “all” civil officers!

Of course, this runs into the problem that nearly all drafting history runs into: unless someone left notes in the margin explaining the change, it’s easy to read it both ways. One explanation for the change (Tillman’s explanation) is that the Founding Fathers thought there was a substantive and important difference between “other” and “all” in this context. They made the change because they wanted to change the legal effect of the Constitution, and considered the correction too obvious to bear comment.

However, another, equally plausible explanation for the change is that the Founding Fathers thought there was no substantive difference between “other” and “all” in this context. They left no comment about the change because they didn’t think it made a difference. In the absence of any recorded debate or discussion about it, both are plausible interpretations of the record.

Nevertheless, it may interest you to know that the group that actually made this change was the Committee of Style. Their job was to “revise the style of and arrange the articles agreed to by the House,” without altering the substance. Indeed, the Supreme Court has held that “"[T]he Committee . . . had no authority from the Convention to make alterations of substance in the Constitution as voted by the Convention, nor did it purport to do so,” and should be interpreted in that light.

As Michael Stokes Paulsen put it with Vasan Kesavan in The Interpretive Force of the Constitution’s Secret Drafting History:

…the draft of the Constitution referred by the Framers to the Committee of Style [should have] the status of a committee report—it is authoritative evidence of legal meaning, but not legal authority. Thus, when the text of the Constitution is unambiguous, it trumps the “second-to-last” draft of the Constitution, as is the case in statutory interpretation; but when the text of the Constitution is ambiguous, its meaning may be informed by the Constitution’s “committee report.” Indeed, the Constitution’s committee report is superior to committee reports in ordinary legislation generally. It is a more prolix form of the final “statute,” and is therefore probably less ambiguous. It is also a more reliable, consistent, and faithful guide to interpretation because it is the product of the “Congress” as a whole.

On the other hand, maybe the Committee of Style violated its mandate and changed the substance anyway, perhaps even by accident. God knows I’ve drafted and re-drafted enough sensitive legal instruments10 in my life that I know how easy it is for a final style pass to turn into “just a couple helpful little substance tweaks,” and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve made a style change that turned out later on to have important legal consequences. The Supreme Court’s 1960s view of the Committee of Style was recently (and ably) challenged by David S. Schwartz in a nifty little 2022 paper.

However, no matter how you interpret the authority of each draft of the Constitution, it’s hard to ascribe specific meaning to specific changes between drafts. As with other examples of Constitution drafting history (Tillman offers several), we just don’t have much of a paper trail to verify, one way or the other, whether the Founding Fathers thought there was a difference between “other civil officers” and “all civil officers” in this clause—and, if so, what that difference was.

(I have a concern about how Tillman and Blackman presented this whole episode. It’s not important to the overall theme of this article, but might be important if you are doing Serious Law Work on Tillman-Blackman, so I will present it in this footnote:11.)

However, we do have a paper trail for what came next. There is undeniably a thread within American law that has consistently held that “officers of the United States” is indeed a term-of-art that (at least under many circumstances) excludes elected officials—including the President.

In 1833, Justice Joseph Story wrote his magnum opus, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, no doubt the single most celebrated academic work on the Constitution before the Civil War. In it, Story examines the Impeachment Clause, including some of the very questions I raised earlier. I will quote Story at length, firstly because I love reading Story, and secondly because I think he’s the single best piece of evidence in Tillman and Blackman’s arsenal (all emphasis mine):

§ 789. Who are "civil officers," within the meaning of this constitutional provision, is an inquiry, which naturally presents itself; and the answer cannot, perhaps, be deemed settled by any solemn adjudication. The term "civil" has various significations… It is sometimes used in contradistinction to military or ecclesiastical, to natural or foreign. Thus, we speak of a civil station, as opposed to a military or ecclesiastical station; a civil death, as opposed to a natural death; a civil war, as opposed to a foreign war.

The sense, in which the term is used in the constitution, seems to be in contradistinction to military, to indicate the rights and duties relating to citizens generally, in contradistinction to those of persons engaged in the land or naval service of the government….

§ 790. All officers of the United States, therefore, who hold their appointments under the national government, whether their duties are executive or judicial, in the highest or in the lowest departments of the government, with the exception of officers in the army and navy, are properly civil officers within the meaning of the constitution, and liable to impeachment.

§ 791. A question arose upon an impeachment before the senate in 1799 [Ed.: the impeachment of Sen. William Blount], whether a senator was a civil officer of the United States, within the purview of the constitution; and it was decided by the senate, that he was not; and the like principle must apply to the members of the house of representatives. This decision, upon which the senate itself was greatly divided, seems not to have been quite satisfactory (as it may be gathered) to the minds of some learned commentators. The reasoning, by which it was sustained in the senate, does not appear, their deliberations having been private. But it was probably held, that "civil officers of the United States" meant such, as derived their appointment from, and under the national government, and not those persons, who, though members of the government, derived their appointment from the states, or the people of the states. In this view, the enumeration of the president and vice president, as impeachable officers, was indispensable; for they derive, or may derive, their office from a source paramount to the national government. And the clause of the constitution, now under consideration, does not even affect to consider them officers of the United States. It says, "the president, vice-president, and all civil officers (not all other civil officers) shall be removed," &c. The language of the clause, therefore, would rather lead to the conclusion, that they were enumerated, as contradistinguished from, rather than as included in the description of, civil officers of the United States. Other clauses of the constitution would seem to favour the same result; particularly the clause, respecting appointment of officers of the United States by the executive, who is to "commission all the officers of the United States;" and the 6th section of the first article, which declares, that "no person, holding any office under the United States, shall be a member of either house during his continuance in office;" and the first section of the second article, which declares, that "no senator or representative, or person holding an office of trust or profit under the United States, shall be appointed an elector." It is far from being certain, that the convention itself ever contemplated, that senators or representatives should be subjected to impeachment; and it is very far from being clear, that such a subjection would have been either politic or desirable.

There’s no two ways about it: this is a clear endorsement of Tillman’s theory by a great American exponent of the Constitution.

On the other hand, Story is explicitly speculating on the reasoning behind an outcome that he agrees “greatly divided” the Senate. He does not indicate that his interpretation of “civil officer” is common opinion among the learned in 1833. To the contrary, Story admits that his interpretation of “civil officer” was not “quite satisfactory… to the minds of some learned commentators” in 1833, and that it had been an open question even in 1799!

Moreover, Story omits the alternative explanation for Blount’s acquittal, which will shortly become important: it was argued at the impeachment trial that Blount could not be impeached because he had already been expelled from the Senate. The Senate acquitted Blount by a vote of 14-11, which means at least 11 senators thought senators were “officers of the United States.” It is unknown how many of the remaining 14 senators agreed with the 11, but voted to acquit Blount anyway due solely to his prior expulsion. The question of whether senators (and, by extension, presidents) were “officers of the United States” for purposes of impeachment was clearly a very close question both in 1799 and in Story’s 1833.

The discussion continued beyond Story. In 1888’s Mouat v. United States, the Supreme Court interpreted an 1873 statute that used the phrase “officers of the United States” in alignment with the Appointments Clause. The Court concluded:

Unless a person in the service of the government, therefore, holds his place by virtue of an appointment by the president, or of one of the courts of justice or heads of departments authorized by law to make such an appointment, he is not, strictly speaking, an officer of the United States. We do not see any reason to review this well established definition of what it is that constitutes such an officer.

Of course, the question before the Court was not, “Is an elected official an officer of the United States?” The question here, rather, was, “Is an employee appointed by a naval paymaster, rather than directly by the Secretary of the Navy, to an office not established by statute, still an officer of the United States?” (Answer: no.) No one on the Court was thinking about the two elected officials at the pinnacle of the Executive Branch.

Nevertheless, the Court’s conclusion seems conclusive. This was only the clearest in a line of post-Civil War cases that all off-handedly mentioned that officers must be appointed (which implies that they can’t be elected), including United States v. Hartwell (1867) and United States v. Germaine (1878).

In 1876, the House impeached Secretary of War William Belknap, who resigned. This set off a harsh debate in the Senate: could they still try someone in an impeachment who had already left office? (This was not only a revival of the same question considered in the Blount impeachment of 1799, but was also a key issue in President Trump’s Senate trial in 2021.)

Joseph Story was central to the Belknap Trial. Story’s name came up over a hundred times during the proceedings, on a variety of different points. However, one fiercely discussed point was Story’s analysis of Blount’s 1799 impeachment and the definition of “officer of the United States”.

For example, as part of a clever indirect argument against prosecuting an impeachment after resignation, Senator Newton Booth said outright (p454, emphasis mine):

Story very ably argues, and refers to this very section of the Constitution in confirmation, that the President is not an officer of the United States.

On the other hand, impeachment manager J. Proctor Knott thought Story’s theories on this point were “to say the least of them, technical and specious” (p145, emphasis mine):

I allude, of course, as the Senate well understand, to the case of Blount, who was impeached in 1798 for conduct inconsistent with his station and duties as a Senator of the United States; but in that case the point was but feebly insisted upon, and never decided by the Senate at all; the whole case having turned, as this court well understands, upon the point that a Senator of the United States was not, in the contemplation of the Constitution, amenable to the process of impeachment under any circumstances whatever. I may add, however, that even the decision of that point has not been accepted by some of the ablest commentators upon the Constitution as sufficient authority to establish a principle; not only because it was the decision of a divided court, 14 to 11, but because the arguments by which it was sought to be sustained, so far as they have been preserved, appear to be, to say the least of them, more technical and specious than sound.

The Senate ultimately returned a mixed decision in Sec. Belknap’s impeachment trial: it seems clear from the record that over two-thirds of the Senate agreed that the defendant was guilty. However, a few crucial senators were persuaded that they couldn’t try an impeachment against someone who had already left office. On the one hand, an absolute majority in each house voted to impeach and convict Belknap. On the other hand, Belknap was acquitted, because the majority fell short of the two-thirds needed.12

Around the same time, a man named David McKnight wrote a treatise on American elections. Tillman and Blackman say that it was an “influential” treatise, but they don’t cite to that, and I can’t find any independent evidence of it on a quick glance, but it certainly could have been influential.

(UPDATE 3 Nov 2023: Tillman evidently saw this, because he today posted a flotilla of citations showing McKnight’s influence, which was indeed far-reaching. I am satisfied, I thank him for the evidence, and I will certainly link this post to any more thorough-going feedback he may provide.)

In that treatise, McKnight said, directly:

From a comparison of the following selections from the Constitution it is obvious that… the President is not regarded as “an officer of, or under, the United States,” but as one branch of “the Government”; [furthermore,] that the Vice President holds an office of “profit and honor,” [and] as the agent to open and count the votes of Electors, an office of “trust”…

This fits the Blackman-Tillman framework with respect to the President, although not the Vice-President. (Blackman-Tillman hold that the Veep does not hold an “office of honor, trust, or profit,” at least, not as described in any constitutional text.)

This strain of thought, especially when it comes to Appointment Clause cases, continues to the present day. As Tillman and Blackman explain, multiple White Houses, Attorneys General, and Offices of Legal Counsel have reached the same conclusions, often citing Mouat directly. As A.G. Francis Biddle put it in 1943: “under the Constitution of the United States, all its officers were appointed by the President… or by a court of law, or the head of a department.” Of course, OLC memos were, like Mouat itself, not usually contemplating elected officials, but rather targeted low-level federal employees who were attempting to shirk this responsibility or that liability by claiming not to be officers. Yet, sometimes, they were thinking about presidents: “When the word ‘officer’ is used in the Constitution, it invariably refers to someone other than the President or Vice President.” So said future Justice Antonin Scalia in a 1974 memo. Either way, modern executive officials frequently use this absolute language to define “officer of the United States.” That language excludes the President.

UPDATE 6 November: Over the weekend, Prof. Tillman called my attention to this 1918 memo, in which the Attorney General (like Scalia in 1974) expressly considers elected officials. See his post about it. We briefly discussed it on Twitter (link 1, link 2; two links because Twitter threading is bad). I thought that this memo tended to undermine his position. He says I am misreading it. I am inclined to believe him, since he has been finely parsing memos of just this sort, on just this subject, since before I learned to drive, whereas my dim awareness of the “officers of the United States” discussion expanded into serious interest only after Baude-Paulsen posted in August. Either way, it is clear that executive-branch memos regarding “officers of the United States” sometimes expressly contemplated elected officials.

Every account of this tradition concludes with Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Co. Accounting Oversight Board, a 2010 Supreme Court case about whether Congress could create executive-branch officers who were essentially immune to being fired by the President. In his decision, Chief Justice Roberts wrote,

The diffusion of power carries with it a diffusion of accountability. The people do not vote for the "Officers of the United States." They instead look to the President to guide the "assistants or deputies ... subject to his superintendence." Without a clear and effective chain of command, the public cannot "determine on whom the blame or the punishment of a pernicious measure, or series of pernicious measures ought really to fall." [citations omitted]

This case is not really on-point, and Roberts wasn’t trying to make a point about the definition of “Officers of the United States.” Nevertheless, he did say the words, “The people do not vote for the ‘Officers of the United States.’”13 Those words can spill out of Roberts’ mouth so easily because they fit very smoothly into a very long tradition of (at least sometimes) reading the phrase “Officers of the United States” to include only officials appointed under Article II, Section 2. If that tradition is correct, then the President, an elected official, is not an “Officer of the United States.”

The Other Side of the Coin

Remember Tillman’s chart? It’s very impressive, and, at this point, if I’ve done my job right, it’s probably looking pretty good—or at least pretty darned plausible:

Tillman has argued that each of these phrases bore a distinct meaning in American law at the Founding. He believes that not all of these terms are ordinary English phrases. Some are legal terms of art.

UPDATE 8 November 2023: The preceding paragraph has been significantly revised in light of comments from Prof. Tillman.14

Legal terms of art are commonplace. You cannot develop a body of consistent law across centuries without stable terminology, which sometimes defies ordinary “everyday” usage. For example, in ordinary English, “consideration” usually means something like “careful thought” or, perhaps, “sympathy.” However, in English-language law, “consideration” means, specifically and exclusively, “the price, motive, or matter of inducement to a contract.” It’s a material thing that gets someone to join a contract, usually money, goods, or services. Thoughtfulness is not “consideration” in a courtroom.

Because legal language so frequently differs from ordinary language, lawyers spend years learning these specialized technical terms. Lawyers spawn vast dictionaries of legal jargon, covering all topics from “a latere” (collateral in succession to property) to “reliction” (an increase of land by the recession of the sea) to “York, Statute of” (a well-regarded English law).

Here’s the most interesting thing (to me) about Tillman’s framework: if “officer of the United States” and “public trust under the United States” and “Office of honor under the United States” are all legal terms of art specific to American law that American lawyers need to know because their meanings differ from ordinary English… then why aren’t they in the legal dictionaries?

It’s not just that there’s no entry labeled “OFFICER OF THE UNITED STATES” or “PUBLIC TRUST” (although there isn’t). The problem is that there is no reference whatsoever to this elaborate framework in any 19th-century legal dictionary I checked. You can use the Internet Archive to search for every reference to “officer of the United States” or “officers of the United States” or “under the United States” (use the quote marks). Here’s Volumes 1 and 2 of Abbot’s Dictionary of American and English Jurisprudence (1879), Volumes 1 and 2 of Bouvier’s Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States, and Black’s Law Dictionary (1891). The phrases are each used occasionally—but always in passing, never in definition.

In all these dictionaries, covering roughly the period 1860-1900, the only reference to Tillman’s theory that I can find is in Black’s: under the entry for “CIVIL OFFICER,” Black’s agrees with Story’s theory that “civil officers” are strictly appointed, not elected… but Black’s interprets that as only applying to the phrase “civil officers,” not to the phrase “officers of the United States” more generally. (Only the latter phrase is used in Section Three.) Abbot’s entry for “OFFICER” makes no attempt to distinguish between different types of officer at all (even where it would be useful).

I did not conduct a comprehensive review of legal dictionary authority. I conducted a rushed search as I tried to write a 10,000-word review of a complex issue by Tuesday, because oral arguments are on Thursday and I still have to write another long article on self-execution by then. So maybe I missed something! Maybe I would have found more evidence if I’d focused on the Founding Era or Joseph Story’s Antebellum! Yet it seems problematic for Tillman’s theory that this “legal term of art,” which he contends is crucial for understanding the Fourteenth Amendment, seems very nearly invisible to the wider legal community at around the time the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified.

There are other contemporary complications for the Tillman framework, several of which Myles Lynch points out in Disloyalty and Disqualification: Reconstructing Section 3. An 1863 federal statute read:

…every person elected or appointed to any office of honor or profit under the government of the United States, either in the civil, military or naval departments of the public service, excepting the President of the United States…

Tillman-Blackman point out (p37) that this uses “under the United States” rather than “of the United States,” which is true, and blunts Lynch’s criticism, but I’ll come back to the “of / under” distinction.

Moving on, in the lower-court decision in U.S. ex. rel. Stokes v. Kendall (26 F.Cas. 702, 1838), Judge Cranch wrote that the postmaster-general is entitled to make his own judgments, independent of the President:

[T]he postmaster-general must judge for himself, and upon his own responsibility, not to the president, but to the United States, whose officer he is. The president himself, although called by the postmaster-general, in his answer, ‘the highest representative of the majesty of the people, in this government,’ is but an officer of the United States, the head of one of the departments into which the sovereign power of the nation is divided.

Tillman-Blackman observe that this precedent isn’t really on-point, because it isn’t squarely about whether the President is considered an “officer of the United States”… but neither are any of the Supreme Court precedents Tillman-Blackman cited in support of their theory here, so, y’know. I find it incautious, at best, to discard Kendall but then turn around and put any weight on the thin reed of 2010’s Free Enterprise Fund.

Lynch unearths scattered other references where the President is plainly referred to as an “officer of the United States,” like an 1824 communication by President Monroe to Congress, which read in part, “when called into service… [the militia] could not be commanded by a regular officer of the United States, or other officer than of the militia, except by the President, in person.” Growe, in her brief, uncovers several more (p28).

Tillman-Blackman acknowledge that there are casual references to the President as an “officer of the United States,” but insist that these are sloppy references expressed in casual “everyday” English, whereas technical legal meaning must carry the day in constitutional interpretation.

However, the constitutional evidence does not all point one way, either. If Tillman’s framework is right, then the President is not an “officer under the United States,” and is therefore immune from the Foreign Emoluments Clause in Article 1, Section 9:

No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.

It would be odd to argue that the President is not covered by this clause, and the weight of historic practice supports this: Andrew Jackson, Martin van Buren, and John Tyler all sought Congressional consent for their foreign gifts, the White House Office of Legal Counsel holds that the President “surely” must ask consent for his foreign gifts, Congress requires the President to do so under the Foreign Gifts and Decorations Act of 1966, and both the Trump Administration itself and several courts ruling on this clause all agreed that Trump was personally subject to it. Tillman replies with a couple examples from George Washington, but stands essentially alone on this.

Or, again, in Article II:

…but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

If Tillman’s framework is right, then a President could be appointed an elector to his own office, which would seem to (very obviously!) undercut the purpose of this clause. It seems that no sitting President has ever served as an elector.

Perhaps Tillman’s theory is not based on the 1787 original public meaning of “officer of the United States” after all, but is simply an earnest, well-meaning attempt to make a bunch of inconsistent constitutional language retroactively hang together using hyperformal strict constructionism, overfit to an infinitesimal constellation of data points strewn across three centuries.

Original Public Meaning

The position that “officer of the United States” was (and remains) a legal term-of-art referring solely to appointed officers is clearly a respectable one. I am not going to sit here and call Joe Story an idiot. The guy’s literally my reddit flair. Nor am I going to call Steven Calabresi or former Attorney General Michael Mukasey dopes. Quite the contrary. Nor is Blackman anyone’s fool. I haven’t read enough of Tillman’s mountains of work to do any more than gently suggest it might be ill-founded.

However, in excavating this, we’ve uncovered not two, but three distinct traditions around the meaning of “officers of the United States”:

The ordinary-English-meaning tradition, aka my dad’s incredulous stare: “What? Of course the President’s an ‘officer of the United States’! The presidency is an office and the President holds it! How could it be otherwise?”

The restrictive legal tradition, aka the Joseph Story / Seth Barrett Tillman / Donald Trump school: “‘Officer of the United States’ is a legal term of art referring solely to appointed officers in the executive and judicial branches.”

We’ve also seen a good bit from a source rarely discussed in this debate: the unrestricted legal tradition. I’m going to call this the Bayard-Knott school, after the managers of the Blount and Belknap impeachments. (We also see reference to this school in Story’s own writing about “learned commentators” unsatisfied with the Blount resolution, in scattered 19th-century references, and in numerous suggestive silences.) This school holds, approximately: “The restrictive legal tradition is technical, specious, and defies ordinary meaning. The presidency is an office and the President holds it. That makes him an ‘officer of the United States’. C’mon, guys.”

Two of these schools view the President as an “officer of the United States.” The third does not. All three of these traditions trace their origins back to the Founding. All three were clearly present throughout American history—although which side enjoys the consensus support of the legal community has, perhaps, waxed or waned. The problem arises rarely enough that it has repeatedly defied final resolution.

So, when we read Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment, and we encounter the phrase “officer of the United States,” which of these three traditions should we follow?

If we had no other information, then I think this might be a very close call. When a text appears to have one original public meaning for the common man, and another original public meaning for lawmakers and lawyers, it is, generally speaking, the lawyers’ meaning that must win out. They drafted legal text in legal language in order to fit into the wider universe of our law. The common man needs to get familiar with the legal meaning of the text before voting on it. The common man is usually educated on the legal meaning of proposed amendments (if it can be called education) through mass media, whether that’s 21st-century memes or 19th-century partisan newspapers.

However, Section Three presents a difficulty: the legal community itself was divided on the legal meaning of “officer of the United States.” When the legal community itself offers us two plausible original public meanings, how do we resolve that?

It will be tempting to say, “We resolve it whichever way gets us what we want.” This is what judges call “weighing public policy concerns,” and it is never a good move.

Fortunately, we are not completely out of information. We have not touched what is, in my view, our single most important source: the framers themselves.

I’ve written before about how identical legal text can take on different meanings over time, and the same legislature enacting the same language may convey very different meanings at different times. For instance, in the Thirteenth Amendment (which outlawed slavery and involuntary servitude), the language “involuntary servitude” referred only to performing labor for private parties. Prison labor is performed for the State, not a private party. Therefore, the Thirteenth Amendment makes no reference whatsoever to prison labor. If the Thirteenth Amendment had originally passed without its “except as a punishment for crime” clause, then the Thirteenth Amendment would still have allowed prison labor. (What the “exception clause” was actually allowing was the now-extinct practice of convict leasing.)

However, in modern times, “involuntary servitude” no longer has that meaning. Most people, lawmakers and the public alike, think prison labor counts as “involuntary servitude.” Several states, including Nebraska in 2020, recently re-enacted their state versions of the Thirteenth Amendment with a revision to remove the “exception clause.” Nebraska lawmakers and the Nebraska public of 2020 understood that doing so would outlaw prison labor, and intended precisely that. From an 1865 perspective, their understanding of the language was completely wrong. Nevertheless, because that was their understanding in 2020, and they passed their amendment, their understanding of that amendment is now the law of Nebraska. Deleting the “exception clause” banned prison labor in Nebraska, even though the “exception clause” had nothing to do with prison labor.

Scholars call this phenomenon “linguistic drift” (and this is a particularly paradoxical instance of it). Even if future Nebraska lawmakers and voters eventually recover the true meaning of the Thirteenth Amendment (perhaps by reading this very blog!), their corrected understanding won’t change the meaning of what Nebraskans did in 2020. Prison labor cannot be re-introduced into Nebraska without another amendment.

Now let’s pull this back to “officers of the United States” and Section Three.

Although we can learn a lot from the 1787 Constitution and other commentators about what “officers of the United States” in Section Three likely meant to its original public, the strongest source of evidence is the people (and the public) who actually wrote, proposed, and ratified Section Three. Whatever those people (and especially that public) thought “officers of the United States” meant is what “officers of the United States” means—at least within Section Three.

So, did they subscribe to the ordinary meaning tradition, the restrictive legal tradition, or the unrestricted legal tradition?

What the Reconstruction Framers Thought

There was virtually no discussion of the phrase “officers of the United States” in the proposal and ratifying debates over the Fourteenth Amendment.

That, in itself, is significant. Ordinarily, the ratifying public learns the specialized legal meanings of proposed amendments through media communications, like newspapers and pamphlets. I can sum up the findings of about six recent law review articles, on both sides of the Trump-disqualification question, in five words: there are no such communications. On the direct question of whether the President is an “officer of the United States,” there is absolute silence. A few have found suggestive comments to one effect or the other,15 but nothing direct.

When the ratifying public is never even informed of the special legal meaning of the terms in constitutional text that is ratified by the public, the ordinary (and quite reasonable) assumption16 is that the text bears its ordinary “everyday” meaning, not a specialized technical meaning.

That seems to agree with the sentiments of the people who wrote the darn thing. The evidence we have indicates that the reason the lawmakers who proposed Section Three did not attempt to communicate any special legal meaning in the phrase “officers of the United States” is because they intended none.

As transcribed by (disqualification-skeptical) Kurt Lash in his forthcoming paper (slightly reformatted):

On May 30th, the Senate debated the new version of Section Three. Speaking in opposition, moderate Democrat and constitutional lawyer Reverdy Johnson claimed that the section was underinclusive because it did not include the President or Vice President. Explained Johnson:

JOHNSON: “But this amendment does not go far enough. I suppose the framers of the amendment thought it was necessary to provide for such an exigency. I do not see but that any one of these gentlemen may be elected President or Vice President of the United States, and why did you omit to exclude them? I do not understand them to be excluded from the privilege of holding the two highest offices in the gift of the nation. No man is to be a Senator or Representative or an elector for President or Vice President—”

At this point, Republican Senator Lot Morrill interjected:

MORILL: “Let me call the Senator’s attention to the words ‘or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States.’”

Johnson then conceded:

JOHNSON: “[p]erhaps I am wrong as to the exclusion from the Presidency; no doubt I am; but I was misled by noticing the specific exclusion in the case of Senators and Representatives.”

This fits nicely into the model we’ve been developing. Johnson, an excellent constitutional lawyer, following Story’s restrictive understanding of “officer under the United States,” argued that the clause didn’t include the presidency. Senator Morrill, a fierce advocate of Reconstruction and the Fourteenth Amendment, corrected Johnson, saying (in effect) that the clause did not follow Story’s restrictive understanding of the term, but the Bayard-Knott understanding that it includes every officer without restriction. Johnson, aware of this competing school of interpretation, accepts the correction and concedes the point. The exchange was not reported in the press, but went uncorrected (indeed, unrevisited) in Congress.

You may object, “Ah-ha! But Johnson and Morrill were discussing the part of Section Three that talks about officers under the United States, not officers of the United States!” However, we have some contemporary evidence to suggest that Congress at the time—rightly or wrongly—made no distinction between “officers of” and “officers under.”

In a unanimous 186617 report by a Select Committee of Congress,18 the committee concluded that “It is irresistibly evident that no argument can be based on the different sense of the words ‘of’ and ‘under,’ as used in these clauses of the Constitution… because they are made by the Constitution equivalent and interchangeable.”

That’s important! 1866 is the very year that the Fourteenth Amendment was proposed. All five of the committee’s members had voted on the Amendment only five weeks before delivering this report, and the committee’s deliberations appear to have overlapped with the vote on the Amendment. (Four members voted for the Amendment, one against.) Evidence does not get more contemporary than this! The chairman of this committee, Rep. Samuel Shellabarger, is widely considered in the literature to be an important voice in the exposition of the amendment’s original public meaning,19 and he would go on to draft the Enforcement Act of 1871 (the Anti-KKK Act) under an expansive interpretation of its provisions.

So when they say that there’s no difference between “officer of” and “officer under,” unanimously, and Congress receives this claim without objection or debate, that’s pretty good evidence that, to this particular legislature at this particular time, there was no difference.20

That makes it difficult to block the force of Sen. Morrill’s exchange with Sen. Johnson. More than that, it profoundly challenges (at least for the Congress of 1866) the assumption at the heart of Tillman’s entire framework: that different word choices necessarily mean substantively different things. Suppose instead that, at least in 1866, the words “officer” and “officer of the United States” and “officer under the United States” all meant exactly the same thing.

Oh, and John Bingham, the author and architect of the Fourteenth Amendment, called the President the “executive officer of the United States” in 1868, along with a cavalcade of other contemporaries cited in Growe’s brief (p40).

There is more evidence (on both sides) that I might delve into, including structural evidence,21 grammatical evidence (Baude-Paulsen dive into what prepositions take what words), evidence of original expected applications, and invocations of absurdity.22 However, at this point, what’s left probably won’t change your mind. All six briefs that discuss this (Growe’s, Trump’s, Growe’s Reply, the Republican National Committee’s, the Constitutional Accountability Center’s, and Gerard Magliocca’s; see the Orientation post for links) are worth reading, and, if you really want to fall down this rabbit hole, there’s legal scholarship that will keep you falling for a lot longer than the 10,000-word length of this blog post.

For now, though, let’s try to make a decision.

The Burden of Proof

Throughout their articles on “officers of the United States” and Section Three, articles that are essential to Trump’s defense in Growe v. Simon, Seth Barrett Tillman and Josh Blackman insist that the burden of proof is on people who think their restrictive technical framework is wrong.

I think that gets it backwards. The Supreme Court has held that a constitutional provision debated and (at least indirectly) ratified by the general public is presumptively written in ordinary, everyday language. Everyone concedes, including Tillman and Blackman, that, in ordinary English usage, the president is an “officer of the United States” (and an “officer under the United States,” too). If we construe Section Three this presumptively correct way, Donald Trump is subject to it.

This presumption can be defeated by evidence. There’s no question that Tillman and Blackman provide some meaningful evidence of the public meaning of the phrase “officers of the United States” in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries which points to a restrictive technical meaning. However, this is balanced by other evidence that this restrictive technical meaning was equivocal, only applied in certain contexts, was not actually widely known by the public (why isn’t it in any law dictionaries?) and/or was repeatedly challenged by legal scholars and lawmakers who adhered to an unrestricted technical meaning of the same phrase. Tillman and Blackman’s thesis is weakest at the very point where it is most crucial to Section Three: in the Congress of 1866, which proposed the Fourteenth Amendment at the very same time that it at least appeared to reject the premises of Tillman’s framework.

This is a murky and conflicted set of data, which pits different elements of textualism against one another. It seems to me that this is a place where different people could look at the same heap of evidence from different perspectives and, acting in good faith, reach different conclusions about it. For just that reason, it is important that we all redouble our efforts to avoid coming up with the answers we want. (Remember my warning.) This makes it Trump’s strongest argument.

However, in my view, this equivocal evidence is not sufficient to defeat the presumption that, in the Fourteenth Amendment, the phrase “officers of the United States” means exactly what my dad thought it meant in the first place. I’ve now spent well over five weeks studying this, but I think my father—like most Americans23—got the answer right in the first five seconds:

“Of course President Trump was an officer of the United States. How could he be anything else?”

Programming Note & a Couple Words on “Self-Execution”

I have now written about insurrection itself, the democratic legitimacy of disqualification, miscellaneous jurisdictional arguments (standing, laches, Minnesota law, the political question doctrine), and now the meaning of “officers of / under the United States.” If you’ve read it all, congratulations; all those words put together were longer than The Great Gatsby.

I wanted to write one more big one before oral arguments on Thursday: a deep dive into Griffin’s Case and whether Section Three is “self-executing” (as the jargon goes) or whether Section Three requires Congress (specifically) to pass some sort of legislation enabling it. This is another serious argument by Team Trump, and it deserves a full treatment here on the Disqualification Nerd Blog formerly known as De Civitate.

However, as I type these words, it is now 2:45 a.m. on Wednesday morning. It is clear as Captain Boday’s skull that I’m not going to be able to write and publish another article between now and Thursday morning. I’ll be lucky to get this one revised over my lunch hour at work tomorrow later today. (Plus, it’s All Saint’s Day, a Holy Day of Obligation for us Catholics, so I’ve got to get to Mass!) Perhaps, if all goes well, I’ll still write something about the self-execution question after orals.

For now, all I can do to prepare you for orals is suggest is that you read the relevant parts of the briefs. (See the Orientation post for links.) That will be, in sequence:

Growe’s Brief (“Petitioners’ Brief”), Section III

Magliocca’s Brief, Section V

CREW’s Brief, all of it

Trump’s Brief, Section II

The RNC’s Brief, Section I-D, kinda

The ACLJ’s Brief, all of it

Growe’s Reply Brief (“Petitioners’ Reply Brief”), Section III

It’s a lot of reading, but honestly probably not more than you were gonna read from me eventually. Just a lot of irritating clicking and scrolling to find all the right parts.

I regret not being able to develop my own thoughts on self-execution fully before oral arguments. I do have some, which I will sketch here:

I think that asking whether Section Three is “self-executing” is a bit of a misnomer. Of course Section Three self-executes. That is, by its own force, Section Three renders some people to be ineligible to be President. The Enforcement Act of 1870 (Sections 14 and 15), which Team Trump loves pointing to ever so much, makes perfectly clear that it isn’t doing the disqualifying; Section Three is.

At the same time, of course Section Three is not self-enforcing. Not even Baude-Paulsen think that, say, a ballot counter can simply refuse to tally votes for Trump on the theory that she has determined Trump is ineligible. Section Three renders someone ineligible for office, but it does not have the effect of removing someone from a ballot, nullifying votes cast for him, blocking certification of his electors, and so on, unless some further mechanism of law enables that enforcement. In Minnesota, Minn. Rev. Stat. 204B.44, which provides for judicial review of candidate eligibility in all elections, provides that mechanism of law.

There’s no real debate here about whether Section Three is “self-executing.” Team Trump is rather arguing that enforcement of Section Three is specifically and exclusively reserved to Congress. I don’t buy it.

My other thought is that I don’t think Growe and Co. need to go so hard in their critique of Griffin’s Case, a decidedly weird case but one with a decent pedigree. I think a careful reading of Tillman-Blackman’s Sweeping and Forcing the President Into Section Three (linked earlier in this article) will reveal multiple ways of rationalizing Griffin’s Case—and those ways, I think, turn out to be compatible with or even supportive of Growe & Co.’s view that Minnesota may, by state law, enforce Section Three. Baude-Paulsen came out swinging hard against Griffin’s Case, which kind of set the tone, but the more I’ve read about it, the more I suspect that a via media is open. Alas, I’ve run out of time to find it before the Minnesota Supreme Court decides the issue.

In any event, I’ll be back Thursday with my report direct from the courtroom!

UPDATE 8 November 2023:

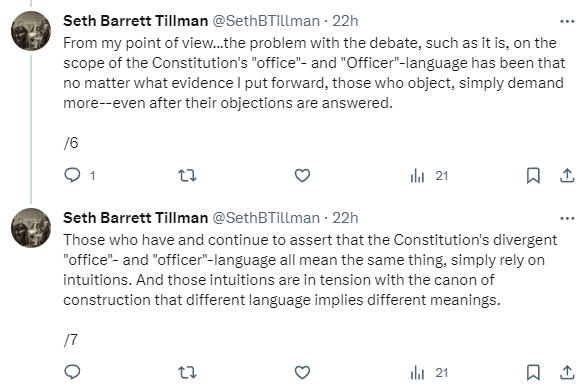

Prof. Tillman has taken the time to offer a couple brief thoughts about this, and I think it’s only fair to give him the last word:

He is quite correct about the canon of construction. When I said that this data “pits different elements of textualism against one another,” the fact that his position applies the Consistent Usage Canon and mine doesn’t was at the top of my mind. The Consistent Usage Canon is a biggie. It’s #25 in Justice Scalia’s book.

UPDATE 21 December 2023:

I call your attention to a very short new paper by lawyer John J. Connolly, entitled “Did Anyone in the Late 1860s Believe the President was not an Officer of the United States?” It’s 4 pages long, an easy read.

Connolly describes a series of newspaper columns that were printed in the Louisville Daily Journal and The Cincinnati Commercial in April 1868. These columns debated almost the precise point we’re concerned with: what did people in the late 1860s think the phrase “officer of the United States” meant, and did they think it included the President?

The Louisville Daily Journal argued that the President is not an “officer of the United States,” for many of the very same reasons recited above. The Cincinnati Commercial thought the Louisville Daily Journal was engaged in idiotic sophistry and insisted that the President was obviously an “officer of the United States,” duh-doy. The two papers were, of course, aligned with opposite political parties, and each had a partisan stake in the outcome.24

So, basically, the same argument we see playing out in editorial pages across the country today! There really is nothing new under the sun!

I don’t vouch for the quality of the legal arguments in either paper. What I find fascinating is what those arguments were, and what light they shed on how Americans thought about these issues in the late 1860s.

Most crucially for me, the Louisville Daily Journal conceded it was an “accepted doctrine” that the President is an “officer of the United States,” even though it vigorously disagreed with the doctrine.

The Reconstruction Congress considered disqualifying all rebels. In fact, at times, they considered disqualifying all rebels not only from taking office, but even from voting. However, this would have disqualified a large proportion of the population of the South—particularly in an era when voting and office-holding were still restricted to males (many of whom had served in the rebel military).

Locking such a broad swathe of citizens out of republican representation might have created problems under the Republican Form of Government Clause of the Constitution. That worry would have been felt especially keenly by the Reconstruction Congress, which was relying heavily on the Republican Form of Government Clause to justify the radical steps it took to ensure that the South would allow Blacks to vote and hold office, such as refusing to admit representatives from former Confederate states until they had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment. However, I am not familiar enough with the historical record to make any broad pronouncements about their reasoning.

Akhil Amar’s America’s Constitution: A Biography, as usual, has a pretty good overview of this fraught period, and I’ve no doubt that you’d pick up a lot of details by osmosis if you just read Kurt Lash’s research on Reconstruction. That’s certainly where I would look for more information on the how’s and why’s of Section Three, even if his conclusions about what Section Three says ultimately differ from mine. The appendix of his forthcoming paper contains every draft considered in Congress, which makes fascinating reading all by itself.

Former President Trump is an historical anomaly: he was the first President ever elected without any prior service in public office or in the military. The day in January 2017 when he took the presidential oath of office was the first time he had ever sworn an oath to the Constitution of the United States. It remains the only oath he has ever sworn to the Constitution of the United States.

Biden can’t do this, because, like all previous U.S. presidents, he took a prior oath to the Constitution—in his case, as a U.S. Senator—and therefore is unambiguously covered by Section Three. Rachel Maddow, like Trump, has never before sworn an oath to the United States, and is therefore not covered by any prior office-holding.

This may have to wait until her term expires. It’s extremely hard to prosecute a sitting president for anything, maybe legally impossible. Long story; not getting into it today.

This is from John Bouvier’s A Law Dictionary: adapted to the Constitution and laws of the United States of America, Tenth Edition (1860). I am using this dictionary because both Trump (in his Reply to Petition) and Baude-Paulsen (in their paper charging Trump with disqualification) agree that Bouvier’s dictionary is an authoritative source of evidence about the meaning of legal terms at the time.

However, I was unable to track down a copy of the Twelfth Edition (1868), which is the edition Trump and Baude-Paulsen each used. That would have been desirable, since the Fourteenth Amendment was proposed in 1866 (and, I believe, took on its fixed original public meaning at that time) then adopted in 1868. The Twelfth Edition is therefore closer in time to the Fourteenth Amendment.

However, Bouvier’s definition of “officer” is substantially unaltered in the Fourteenth Edition of 1878, so I’m not really worried that I missed some crucial development in the meaning of the word “officer” between 1860 and 1866.

Here are all 25 other references to the Presidency as an “office”:

“The Senate shall chuse their other Officers, and also a President pro tempore, in the Absence of the Vice President, or when he shall exercise the Office of President of the United States.”

“Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office…”

“No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.” (2x)

“In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.” (2x)

“Before he enter on the Execution of his Office, he shall take the following Oath or Affirmation:--"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” (2x)

“The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

“But no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States.”

“No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice, and no person who has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected President shall be elected to the office of President more than once. But this Article shall not apply to any person holding the office of President when this Article was proposed by Congress, and shall not prevent any person who may be holding the office of President, or acting as President, during the term within which this Article becomes operative from holding the office of President or acting as President during the remainder of such term.” (6x)

“In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President.”

“Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.” (2x)

“Whenever the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, and until he transmits to them a written declaration to the contrary, such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice President as Acting President.”

“Whenever the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.”

“Thereafter, when the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that no inability exists, he shall resume the powers and duties of his office unless the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive department or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit within four days to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office. Thereupon Congress shall decide the issue, assembling within forty-eight hours for that purpose if not in session. If the Congress, within twenty-one days after receipt of the latter written declaration, or, if Congress is not in session, within twenty-one days after Congress is required to assemble, determines by two-thirds vote of both Houses that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall continue to discharge the same as Acting President; otherwise, the President shall resume the powers and duties of his office.” (4x)

TLDR: the presidency is an office

The “I’m gay! I’m gay!” guy in that video—different times, huh?—is New Jersey Governor Jim McGreevey, a scandal you definitely forgot.

Here is the same table presented as text, for the benefit of screenreaders and copy-pasters:

Officer (simpliciter)

Holds an office – includes those holding “office … under the United States” as well as those holding elected positions: The President, Vice President, and Speaker of the House and Senate President Pro Tem

Succession Clause, Art. II, sec. 1

Officer of the United States

Appointed officers in the executive and judicial branches – subset of those holding “Office … under the United States”

Appointments Clause, Art. II, sec. 2

Commissions Clause, Art. II, sec. 3

Impeachment Clause, Art. II, sec. 4

Oaths Clause, Art. VI

Office … under the United States

All positions created, regularized, or defeasible by federal statute including (nonelected) legislative branch positions

Incompatibility Clause, Art. I, sec. 6

Rebellion Disqualification Clause, Amdt. XIV, sec. 3

Religious Test Clause, Art. VI

Offices of Honor/Trust/Profit under the United States

Subsets of “Office … under the United States”

Honor: Honorary offices with no regular duties, salary, or other emoluments

Trust: Offices with regular duties that are not delegable, e.g., an Article III judge

Profit: Offices holding regular salary or other emoluments

Disqualification on Impeachment Clause, Art I, sec. 3

Foreign Emoluments Clause, Art. I, sec. 9

Elector Disqualification Clause, Art. II, sec. 1

Public Trust under the United States

Elected positions and constitutionally created offices – i.e., the President, Vice President, Members of Congress, and Members of an Article V national convention

Religious Test Clause, Art. VI

Office under the Authority of the United States

A superset of “Office … under the United States.” It also includes federally supervised offices, even if not federally created (such as mobilized militia officers)

Domestic Emoluments Clause, Art. I, sec. 6

Yes, the second of these papers came out the same day Growe v. Simon was filed. Several papers cited here have come out since then. How’s it feel being on the very cutting edge of legal scholarship?

I’m not even joking with that link. Making new cards in an old card game, making sure that they do the complicated things you want them to do, without causing problems for other cards, in a sprawling game with “common-law” rules, where oral tradition sometimes trumps the actual current rulebook, and—oh yeah!—you have to accomplish everything you want and explain all exceptions and timings in no more than 30 words to fit the three-line template… let’s just say that, after months of hard work, that final “style pass” before the set goes off to the Art Department will put hair on your back.

I’m no James Madison. I’m not even an Abraham Baldwin. I’m just saying I know how drafting mistakes get made, because I’ve made enough of them, and then players yell at me.

I originally picked the Impeachment Clause as my example of how the Constitution’s drafting history supports Tillman and Blackman’s theory because Tillman and Blackman themselves made this particular passage sound so convincing.

Before I explain how my convinced became concerned, I have to explain the history of this text, which I simplified above. The “first draft” I shared is actually two drafts of the Constitution smushed together.

The first sentence of the “first draft” (“He shall be removed from his office on impeachment…”) was in the August 6 Draft by the Committee of Detail (Article X, Section 2).

The second sentence of the “first draft” (“The Vice President and other civil officers…”) was appended to Article X, Section 2 on September 8, as detailed in Farrand’s Records, Volume 2, p545. It was not appended right next to the other impeachment sentence, but hung out at the end of the section instead.

The “final draft” I presented was (as I explained above) compiled by the Committee of Style. The Committee of Style text became the final form used in the Constitution, Article II, Section 4. The Committee of Style took the two disparate sentences from the first draft, pushed them into the same section, and knitted them together. They had to pretty well rewrite both sentences in the process, and had to align the result with corresponding revisions elsewhere in the text. Lots of words changed, for lots of reasons.

My point is that this passage has a messy drafting history, and there’s several ways of reading that history.

Now, here is how Tillman and Blackman present this messy history (p9). When I read their article, I knew none of the above, and I found it very persuasive:

In the Impeachment Clause, the phrase “[President, Vice President,] and other Civil officers of the U.S.” was changed to “President, Vice President, and Civil Officers of the U.S.” And in its final form, the Impeachment Clause became: “President, Vice President, and all civil Officers of the United States.” The Framers changed the word that preceded “Civil Officers of the United States” from “other” to “all.”

This and other similar alterations to the draft constitution’s “office”- and “officer”-language were significant. First, these revisions show that this language was not modified indiscriminately. The Framers paid careful attention to the words they chose. Second, the use of “other” in the draft constitution shows that at a preliminary stage, the Framers used language affirmatively stating that the President and Vice President were “Officers of the United States.” But the draft constitution’s use of “other” was, in fact, rejected in favor of “all.” The better inference, arising in connection with the actual Constitution of 1788, is that the President and Vice President are not “Officers of the United States.”

Tillman and Blackman elide the whole messy situation of the two sentences in two different places by simply ignoring the first sentence. They replace it with “[President]” in square brackets. If you only read their article, you have no idea there even are two sentences, much less that they’re from different parts of different drafts added on different days.

I think this is misleading. Tillman and Blackman make it sound like the Committee of Style already had a draft of the Impeachment Clause almost identical to our own, except that the Committee really carefully and deliberately changed exactly one word in this clause: a tactical strike changing “other” to “all.” That makes the change seem super-deliberate, and therefore presumably meaningful. They also seem to (mistakenly?) suggest that this was a two-step process, where the Committee first removed “other” and then, later, inserted “all.”

But that’s not really what happened here. The Committee of Style rewrote two sentences to make them fit together, both with one another and with other amendments to the original plan of the Constitution. The pages of Farrand’s Records Tillman and Blackman cite show that this was a one-step process, not a two-step process. Words were dropped, words were added, and words were changed. William M. Treanor even argues that the Committee of Style dropped the words “against the United States” in order to advance Gouverneur Morris’s federalist agenda, because text-drafting is full of skullduggery and always has been. However, Morris’s agenda does not seem connected to the “officers of the United States” controversy.)

It’s still plausible to see the change from “other” to “all” as a deliberate choice, as Blackman and Tillman do, but, now that I’ve looked into the history, it’s a lot less persuasive (at least to me) than it was when I first read their paper. It certainly depends on a non-mainstream view of the work of the Committee of Style.

I don’t think for a minute that Blackman and Tillman were deliberately misleading anyone. I don’t even think there were engaged in unconscious Occam’s Brooming. The way they presented this text was a perfectly legitimate way of presenting it, given the scope of their project and the constraints of a law review journal. Heaven knows how often I use square brackets to shorten a text or to keep an article from getting derailed into irrelevant distractions. It’s a legitimate and honest strategy.

Nevertheless, I think it made their evidence look stronger, in this instance, than it was. This experience makes me wonder what other complications and wrinkles and doubts about their thesis I might find if I closely examined every citation in Tillman and Blackman’s paper. Perhaps you are a lawyer, and perhaps you are now wondering that, too.

You may recall that this is almost exactly what happened to Donald Trump in his second impeachment: it was clear that two-thirds of the Senate believed him guilty, but Trump had just left office, and enough senators were persuaded that they couldn’t prosecute him that they voted against conviction. It’s like poetry, it rhymes.

Of course, the people don’t vote for President, either. The people vote for electors, when their states allow them to do so, and those electors may or may not, in turn, cast votes for the preferred candidates of their constituents. The President is formally “elected” only by other federal officials, the presidential electors.

This paragraph originally read:

Tillman is certain that each of these phrases bore a unique and distinct meaning in American law at the Founding. That is, he is convinced that these are not ordinary English phrases, but rather legal terms of art.

Rather than trying to characterize Tillman’s objections myself (and risk mischaracterizing them), I’ll let him speak for himself. Here is what he said to me about this paragraph:

I squarely stated that Calabresi et al were wrong about the scope of the Incompatibility Clause. That square statement does not extend to each element of Baude's Jotwell chart.

[…]