“Letters to My Daughters” is a series of letters (#1, #2, #3, #4) I will send my children, when they are teenagers, about our Catholic religion. They are, of necessity, opinionated, and, in light of their audience, paint certain things as I truly see them but very broadly. Of course, your feedback and advice are welcome, or I wouldn’t be posting any of it in public.

Hey.

Yeah?

Do you ever wonder why we’re here?

It's one of life's great mysteries, isn't it? Why are we here?

I mean, are we the product of some cosmic coincidence, or is there really a God watching everything? You know, with a plan for us and stuff?

I don't know, man, but it keeps me up at night.

…

…What?! I mean, why are we out here, in this canyon?

Oh.

Uh… yeah.

What was all that stuff about God?

Uh, hm? Nothing.

You wanna talk about it?No.

You sure?

Yeah.—Grif and Simmons, Red vs. Blue: The Blood Gulch Chronicles, opening lines

(this show was before your time and, honestly, that’s okay)

My dear daughter,1

In the last letter, I prepared us to take the first steps of a Quest with Faith and Truth, a Quest to answer the most important questions: Who am I? Why am I here?

Unfortunately, the moment we set out, we already find ourselves in a morass. You see, our culture has already given you answers to these questions. The culture’s answers are everywhere. They’re the baseline assumption of every television show, nearly every school textbook, and our whole code of laws. Mom and I could not shield you from these answers if we tried. They are simply the air we breathe. The culture gives us assumptions ingrained so deep that we not only don’t notice them, but struggle to imagine a world without them.

Unfortunately, our culture’s answers are wrong, and we will need to expose why before we can make any real progress. This will require a little history, but I will try to make it a little more interesting than Professor Binns’ class—or, at least, shorter! You’ve heard some of this from me over the years on the drive to Mamie & Pops, but, in this letter, I’m going to try and pull it all together.

For several centuries in medieval Europe, scholars worked together to figure out how the world works at the most fundamental level. (This is called ontology, part of philosophy.) Today, this group of medieval scholars is called the Scholastics. (St. Thomas Aquinas, my confirmation saint, was the most famous Scholastic.)

The Scholastics drew up a reasonably complete picture of the basic ordinary things of the world—trees, rocks, people, tables, and so forth—and how they exist and interact. Building on the work of the greatest ancient philosopher, Aristotle, the Scholastics described cause and effect, act and potential, generation and corruption, and many other basic features of existence. Unlike Grif and Simmons, the Scholastics realized they couldn’t ask the really big questions until they’d figured out more basic answers about how the world around them actually worked.

They discovered, unsurprisingly, that the world is fairly complicated! There’s a lot going on under the hood! When you throw a brick through a window, the interaction between you, the brick, the window, the shards of glass that fall from the window, and the universe itself involves many basic features of existence! (Features like potencies, identities, and four different kinds of cause. We’ll come back to some of these in later letters. Others can wait until you take metaphysics in college.)

Then, about four hundred years ago, a new generation of philosophers arose. Most people call these philosophers the Moderns, but I prefer to call them the Mechanics. The Mechanics asked a very interesting question: can’t we simplify the Scholastic model? The Scholastics had “actuality” and “potency” and “essences” and “universals” and a dozen other things in their ontology. But is all that complicated stuff really necessary? Couldn’t we explain those complicated ideas as merely manifestations of other, simpler ideas?

Specifically, the Mechanics asked: what if the entire world were a kind of clockwork machine, made up of colorless, odorless, featureless ball-bearing particles bouncing off one another aimlessly, governed by just a few “laws of motion”? What if there really were no such thing as a brick, a window, or your body? What if bricks, windows, and bodies were just different arrangements of the ball-bearing particles bouncing off one another? Then we wouldn’t need to reason about bricks and windows and humans (and their various “essences” and “powers” and “potencies”). We would just need to figure out what the ball bearings are going to do! Wouldn’t that be much simpler?

This was a great question. You should always ask, “Can this idea be simplified?” However, in this case, it turned out that the answer was “no.” The Mechanical model didn’t work.

Of course, the Scholastics agreed with the Mechanics that everything we can see and touch is made up of other, smaller parts. They agreed it was very important to study those parts. Neither the Scholastics nor the early Mechanics knew about atoms, fermions, or the quantum foam, but a lot of physical substances did turn out to be composed (in a sense) of a lot of ball-bearing-like particles bouncing off one another.

But the Mechanics were not satisfied with studying the ball bearings as parts of a larger whole. In their desire to “clean up” Scholasticism, the Mechanics insisted that the ball bearings were the only things that existed—or, at least, the ball-bearings were the only things that could be known and understood.2

In the Mechanical view of the world, then, there’s not really any such thing as a tree or a brick or the color red, because those are just names we give to different arrangements of the ball bearings, nothing more. Anything that isn’t made of ball bearings, or isn’t governed by the ball-bearings’ “laws of motion,” can’t really exist, or at least can’t be known. God, the human soul, the moral law, and free will? Sure, those are all nice ideas… but that’s all they are, according to the Mechanics. Some people believe in these ideas, other people don’t, but, since they aren’t made of ball bearings, nobody can say why or who is right. “Free will” would violate the ball bearings’ “laws of motion,” so any free will we actually experience can only be an illusion.

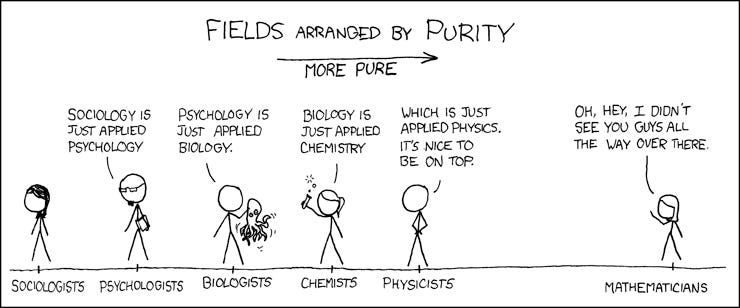

This may sound like a loose description of Science, but that’s just what they want you to think. This isn’t science. The Mechanical Philosophy came from philosophers. Scientists all think this way today, but that isn’t because science has “proved” it. It’s because scientists always think whatever trendy philosophers thought fifty years ago.3 In fact, when you work out all the implications of the Mechanical Philosophy, it makes science impossible. (To mention just one problem: the Mechanical Philosophy and the Scientific Method are not made of ball bearings, either, so, if the Mechanical Philosophy or the Scientific Method are true, how could we know about it? According to the Mechanics’ own rules, we can’t.)

The Mechanical position doesn’t work. It never worked. A number of really important—and obvious—features of the world became inexplicable under the Mechanical worldview. (We’ll come back to that in a few minutes.) It was pretty clear, pretty early on, that the Mechanics’ attempt to simplify the Scholastic explanation of the world, though laudable, had failed. The Mechanics retorted that they just needed some more time to work out the details.

There were a lot of reasons the world wanted the Mechanics to succeed, and if I tried to explain them all this really would turn into a Professor Binns lesson. Quickly: The devastating European Wars of Religion gave Europe a big appetite for a philosophy that could tell everyone to chill out and agree to disagree about religion—which is exactly what the Mechanical philosophy said everyone should do. Major successes in mechanical science from Newton, Kepler, and others made people think that the Mechanical philosophy was also successful. Late Scholastics, grown complacent on the triumphs of their forefathers, had let their school of thought fall into decadence, so the world was looking for alternatives. The rediscovery of writings by the Roman philosopher Sextus Empiricus changed the way people think about knowledge, and so did the Protestant Reformation; both made it harder for people to accept the Scholastics’ complicated explanation of the world.

Everyone was cheering for the Mechanics, so, when they asked for more time, we gave it to them.

That was four centuries ago. We’re still waiting for the Mechanics to deliver. Alas! If anything, they’ve made the situation worse. Two centuries ago, they began to have problems describing language. One hundred years ago, they realized they couldn’t defend math. They are never going to fix these problems. They are fundamental to the Mechanical worldview.

However, our culture decided to give them even more time to work out the “bugs” in their philosophy. In fact, we went further than that: we decided to just assume that the Mechanics would eventually succeed. Our culture treats their philosophy as though it were already proved, even though it hasn’t been. You see this everywhere.

In television shows and video games, everyone agrees on the laws of physics—the ball bearings. They politely decline to talk about anything else. On the very rare occasion that anyone on T.V. does talk about something beyond matter—like souls, or God, or even astrology—it’s nearly always treated as a load of mystical woo-woo that nobody can really actually understand through rational thought. If religion is treated as true, it is always as something that can only be known by unreasoning “faith” (which, as we saw in Letter #2, is not faith at all).

Since the Mechanical view is that there isn’t really any such thing as morality, T.V.’s idea of “morality” (usually) amounts to nothing more than making decisions based on emotions and platitudes. That’s a big problem! Reason is the same for everyone, but emotions aren’t. Since we have different emotions, what feels “right” to you might feel “wrong” to me. How can we resolve our disagreements? According to the Mechanics, we can’t. There are no ball bearings in ethics, and ball bearings are all the Mechanical Philosophy accepts. All we can do is hope that people who disagree with us will eventually experience the same emotions as we do.

Sure enough, this is essentially the plot of every season of My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic. (It’s also deeply ingrained in Star Trek and Doctor Who, my favorites. Heck, I like MLP, too!) Textbooks, science, and the law all do the same thing… except that they are (often) even more shameless about embracing the Mechanics’ idea that there are no objective, knowable moral laws.4

Let’s return to the Big Questions and see how our culture, still in thrall to the Mechanical Philosophy, answers them.

Who are you? According to our culture, you are a consciousness (or, more likely, a delusion of consciousness) attached to billions and billions of fluctuating ball-bearing particles. Why are you here? To have as many pleasing experiences as you can before that consciousness winks out of material existence. With these answers, the Mechanics created both of the two leading world religions today:

for those who are convinced that the ball bearings are really definitely absolutely the only things that exist: materialist atheism; and

for those who suspect that there’s more than the ball bearings: Doesn’t Matterism, which teaches that, since we can’t know anything specific about any world beyond the ball bearings, we should just chill out and accept everyone else’s beliefs about them as equally true.

Although atheist materialists are still relatively rare, most people today are Doesn’t Matterists. The Mechanics have won the culture completely.

However, the Mechanics are wrong.

The Mechanical view does not work. There are a number of basic features of the world that the Scholastics were able to explain, which the Mechanics did not, have not, and will not ever be able to explain—because explaining them would require them to adopt “overcomplicated” Scholastic ideas about the world. There are many examples of this, but, so that I do not bore you to tears, I will limit myself to three:

First, perfect circles. You can conceive of a perfect circle. So can I. We can talk about the features of perfect circles; we can calculate their diameter and their area. Yet no perfect circle has ever existed in the ball bearing world! Every “real” circle exhibits minor deviations from the “ideal form” of a circle. Even in math class, drawing with a compass, our circles are only approximations of perfect-circleness. Our calculations of their area are, therefore, always slightly wrong. Yet you and I are both able to access the concept of the perfect circle, even without ever having seen one—and the concept we are accessing is the same concept! Where did this physically impossible concept come from?!

Moreover, even if you and I never existed—even if every human were wiped from the face of creation—the mathematical proofs we have discovered about circles would still be true. In other words, we are able to know things, with certainty, about entities that are not composed of ball bearings and never could be.

Scholastics accounted for this fact by adapting an old Greek idea that the realm of matter is arranged by immaterial patterns called forms. Although matter often falls short of perfectly replicating the patterns, the patterns themselves are still every bit as real as the matter. Mechanics think that’s stupid: patterns are just illusions our brains impose on a fundamentally chaotic world, so they account for our knowledge of math by putting cotton in their ears and singing “la la la”.

I’m not being entirely fair to the Mechanics. They actually spent much of the Twentieth Century trying to explain how math could be compatible with the Mechanical view. The problem is… they failed. W.V.O. Quine spent his life trying to reduce every single thing in human experience to ball bearings, including math, but he got stuck on numbers. He couldn’t find a way to get rid of numbers. Nobody can, because numbers are a lot like perfect circles.

Second, water. Everyone knows that water is H2O: two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom, many times over. That’s true enough. But it isn’t the full truth. After all, actual hydrogen burns! If water contained actual hydrogen, we would be able to set water on fire (or at least set the hydrogen in the water on fire). Instead, water is famously the thing that puts out fires!

Another difficulty: the boiling point of hydrogen is 420° below zero. The boiling point of oxygen is 300° below zero. What about the boiling point of water? If water is made of hydrogen and oxygen, its boiling point should be somewhere between -420° and -300°. Instead, the boiling point of water is 212° above zero.5

Of course, this is because the oxygen and hydrogen in water are bonded to one another, and their bonding radically changes their properties. But that’s precisely the point. Their chemical bond represents a new pattern, which subsumes the individual atoms and turns them into parts of a new whole. The original atoms still exist, in a sense. You can even get them back, with their original properties, by running an electric current through the water. But, as long as the atoms are bonded together as water, the water itself is—in a very important sense—more real than the hydrogen and oxygen atoms which make it up. The properties we taste, feel, and see are those of water, not hydrogen or oxygen.

A Greek named Parmenides (and his famous disciple Zeno) once showed that, if the whole world were just ball-bearing atoms governed by a handful of laws of motion, chemical transformations like H2O becoming water simply could not happen. In fact, if the world were purely mechanical, nothing could change or move in any way. Parmenides (who thought a lot like a Mechanic) thought this meant that the entire visible world, which is always changing, must be some kind of bizarre delusion. Aristotle just thought it meant that the Mechanical view was probably wrong. Aristotle developed a new version of the theory of forms to deal with Parmenides, which the Scholastics appropriated. The Mechanics, who reject immaterial forms because they aren’t made of ball bearings, think the best answer to the problem of change is to put extra cotton in their ears and sing “la la la” louder.

Third, your mind. If a dragon attacks you, a lot of physical events happen: photons strike your eye, which sets off a cascade of physical events in your optic nerve, the visual cortex, and other regions of your brain. These events are accompanied by you experiencing a set of thoughts or feelings like: “Wow! Look at the majesty of its wings! See how its red scales glitter like a sparkle-pen! That’s a dragon!” Meanwhile, as the dragon claws your skin, a similar chain reaction leads from the nerves in your skin to your neurons firing in a particular way that is associated with the sensation you actually experience: horrible pain. The attack may also set off a chain reaction that leads up to your brain and back to your arm, causing your arm to fly up to shield your face. Finally, a different network of neurons starts firing, and, as they do, adrenaline floods your body, and you experience the panicked thoughts, “But dragons aren’t real! Is this real? If it is real, how can I escape alive?”

Objectively, neurons are firing and nerves are responding. Subjectively, though, something we call “you” is having a world of experiences: terror! wonder! pain! redness! dragons! planning! glitter! sparkle-pens! These experiences are not made of neurons and could not possibly be so. We can illustrate this by an example. (This is called the Mary’s Room thought experiment.)

Suppose you locked a child in a black-and-white room from birth, and taught her color theory through a black-and-white speaker with black-and-white books. Eventually, she knows every physical, ball-bearing fact there is to know about colors: photons, the visible spectrum, the brain pathways triggered by seeing the color red, the theory behind hue and saturation, the whole gamut of color theory. For twenty years, she lives in a world of perfect black-and-white, but she learns more about redness than anyone you have ever met. Then, one day, you open the door and hand her an apple. It is the first time she has ever seen something red. She says, “Wow!” Now she not only knows what the physical facts are; she knows what it means to experience red. If that experience were made of neurons, Mary would already know what it is to experience red by studying the neurons as she has. She doesn’t, because it isn’t.

We can come at it from another angle, too. If the Mechanics are right about the mind, then there must be a pattern of ball-bearing neurons which, when connected, become the thought “There’s a dragon in my back yard,” referring to the specific dragon in front of you. The Mechanics will argue that this process of forming a thought out of neurons is just like sending a (rather urgent) letter to the town dog catcher asking for help: your pen sprays a lot of ink on the page in a certain pattern, and, when the dog catcher reads the pattern, it becomes the sentence, “There’s a dragon in my back yard,” and the dog catcher thinks about the specific dragon in your specific back yard. Reading the message in ink and consequently thinking about the dragon, they say, is no different from reading the message in neurons and thinking about the dragon.

However, that doesn’t hold up. The ink on the page doesn’t inherently refer to the dragon. Letters and words aren’t inherently meaningful. By themselves, those ink splotches are just splotches. We humans, using our minds, breathed meaning into those patterns. If neurons work the same way as ink, then the pattern of neurons which “spells out” the thought, “There’s a dragon in my back yard” aren’t inherently directed to dragons at all. Even if the Mechanics are right, then, the mental experience we have of thinking about that specific dragon still has to be “breathed in” from somewhere beyond the neurons. Since this problem bedevils every Mechanical explanation of thought,6 it turns out that the directedness of our thoughts has to come from something non-Mechanical, something not made of matter or energy at all.

The Scholastics understood the mind as one aspect of a special kind of immaterial pattern (which, again, they called a form). Like all patterns, the human form is nothing without matter to arrange (in this case, brain and body), but the form is itself immaterial.7 We directly experience this immateriality every time we think about anything or use any of our senses. Mechanics go to enormous lengths to deny this obvious and nearly universal human intuition, but I will spoil a whole upper-division philosophy class for you here: they have made no progress on the origins of subjective, self-conscious thought in four hundred years, and, though they continue to insist that they’re on the verge of a breakthrough, they don’t even have the beginnings of a plan for actually carrying one off.

I could not possibly give you a complete Scholastic philosophy of the mind (much less a Scholastic philosophy about the rest of the world!) in the space of a letter—not even a letter as long as this one. If you’re interested in reading more about the mind, I warmly recommend Philosophy of Mind: A Beginner’s Guide, by Edward Feser. It’s a college-level text, but it does a great job explaining both why all the different Mechanical theories of mind seem correct to some current philosophers, and then tells you where exactly each theory is hiding the ball. For a typical example of modern Mechanic arrogance about the mind—long on assertions but lacking evidence or argument—look up “Minds are Simply what Brains Do,” a short presentation by Marvin Minsky of MIT. For a broader critique of the Mechanical Philosophy and a deeper explanation of the Scholastics, you have several good options: Edward Feser’s The Last Superstition (which is very readable but aggressively polemical, as was the fashion in 2009), Feser’s Scholastic Metaphysics (which is sedate but much denser and more challenging), or Ralph McInerny’s Handbook for Peeping Thomists (which is a great introduction to the Scholastic model, now free online, but pretty much ignores the Mechanics).

All I wanted to do today, though, was to help you look clearly at the Mechanics’ model of the world. I wanted you to see that it isn’t the only model (even though everything you’ve ever seen on TV or in movies says it is), and that that’s quite lucky, because the Mechanical model is wrong. These are already pretty big, difficult ideas, and I’m proud of you for making it this far.

The Mechanical Philosophy dominates our culture and deeply shapes the way we think about everything, from science to morals. It teaches us, from our youth, that the most important truths are either gibberish or (at best) unknowable, and that every explanation of the world that involves anything except ball-bearing particles is “mystical” or “magical” or otherwise strange, private, and vaguely embarrassing. Yet the Mechanics are just wrong. The world simply isn’t a bunch of ball-bearing particles bumping into one another guided by a handful of abstract “laws of nature.” Even if we can’t be sure that the Scholastics are right, we can be sure the Mechanics are wrong. Their model cannot account for circles, water, minds, or a million other obvious things, but it lives on because our culture is cheering for them. We must learn to actively resist the Mechanics’ habits of mind, or we will never be able to see the world as it truly is. The world, as it truly is, as it obviously is, is far richer than they can admit, teeming with immaterial things that really exist, from numbers to minds.

This is important, because, in the next letter, we are going to venture to deduce a few facts about certain immaterial things. To those still in thrall to the Mechanical Philosophy, these deductions are inherently absurd, and require a ridiculously high burden of proof. To those who have already glimpsed the immaterial aspects of our world, though, there’s nothing special about further deductions.

As we will see, this simple difference in one’s starting point has vast consequences.

Love,

Dad

This post owes a great deal to Edward Feser’s books, especially Philosophy of Mind and The Last Superstition.

It also owes much to Fr. Michael Tavuzzi, O.P., who taught an excellent (and wickedly funny) course in modern philosophy at the Angelicum in Fall 2009. My 40-odd pages of looseleaf notes from that class (“Aaron’s Gang”) remain a treasure to me. Long ago, the old witch-hunter could be found in certain online haunts, but he has vanished, and I miss him.

Neither writer would endorse everything I’ve written here, and would likely object to some of the shortcuts I took in trying to explain this stuff to a young teen.

This is obviously not altogether fair to the Rationalist school: Descartes, Malebranche, Liebniz, Spinoza, and their lot. However, I’m trying to summarize a millennium of philosophical thought in 4,000 words for a thirteen-year-old, so compromises have to be made.

Besides, the Rationalists lost. They were routed by the Empiricists. There are more people today who believe in Xenu than in monads, but David Hume, Thomas Hobbes, and (yes, I’m counting him) Immanuel Kant are revered across the world.

My hottest physics take: Schrodinger’s Cat should be blamed far more on Bertrand Russell and the positivists than on actual quantum physics data.

…a position that philosophers call “relativism.”

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy reminds me that, within the field, a distinction is sometimes drawn between moral skepticism (there are no moral truths) and moral relativism (moral truths are real but subjective). Colloquially, however, they are interchangeable, and, practically, they’re nearly identical anyway.

Shamelessly wrenched from David Oderberg, Real Essentialism, 2007, p75, quoted in Feser’s Scholastic Metaphysics.

I think this is too complicated to throw at a young teen, but an increasingly popular way of escaping the various “hard problems” of consciousness is called panpsychism. Panpsychism posits that everything material is conscious at a certain level, and therefore everything experiences at least a limited, rudimentary subjectivity. According to this theory, we are conscious, stars are conscious, and electrons are conscious. Your doorknobs are conscious. Your oven timer is conscious (and so, separately, is your stovetop). It’s like The Brave Little Toaster on steroids. According to the theory, we can’t directly observe this for the same reason we can’t directly observe consciousness in fellow humans, but, nevertheless, everything is conscious.

I completely misunderstood the appeal of this theory the first time I heard it (where I dismissed it for lack of evidence), but I’ve since learned that the appeal is quite simple: the problem for materialists is that they can’t explain why human and perhaps animal brain matter seems to generate consciousness and subjective experience. This makes our brain matter seem special, even magical. (To a materialist, anything not physical is magical.) This specialness cries out for special explanation, but, since the brain appears to be composed of ordinary matter like everything else, the explanation is not available.

In other words, the panpsychist has given up on explaining why brains are special. Instead, he makes his big move: he denies that brains are special. By ascribing consciousness to all matter, not just brain matter, he swerves around the need to explain why our brains are special.

Of course, this leads to some extremely weird places. What is it like to be an oven timer? Or an electron? Or the space bar on my keyboard? On this theory, those things are all having some kind of experience right now! That’s, uh, pretty crazy!

But “that’s crazy” is not a great argument in philosophy, because every coherent picture of the world requires swallowing a few things that sound crazy.

The larger problem for panpsychism, in my view, is that it still fails to actually explain anything. Even if every material thing has the immaterial experiences of consciousness, intentionality, and even rationality, that still doesn’t explain how the material is capable of causing these inherently, self-evidently immaterial experiences! It doesn’t solve the problem; it just sweeps it under the rug! (Even if it didn’t, it would still lose to hylomorphism on parsimony.)

As I said, this is too much for my 13-year-old. However, if panpsychism continues to gain ground, I may need to put some reference into the main body of the letter before I hand it to my youngest daughter in a few years, so this footnote will serve as my notes if that eventuality arises.

The Scholastics call this form a “soul.” However, what they meant by that word was radically different from what most people mean by that word. The popular conception of the human soul depicts it as a kind of invisible spiritual energy field, or at least as a kind of ghost inhabiting the human body. That popular notion comes straight from the Mechanics, who considered dualism of this sort the only serious competitor to materialism. To the Scholastics, the soul was simply the immaterial form of the body (the whole body, not just the brain), not a ghost controlling a body through spooky action.

This Scholastic concept of a soul is so alien to what my kids have “learned” about souls through cultural osmosis that, even though I’ve spent years laying the foundations for them to understand the Scholastic soul, it still doesn’t seem worth explaining in this letter. Thus, I just avoided the term entirely today.

As a chemical engineer, I think the problem with your discussion of water vs hydrogen and oxygen is that atoms are not fundamental particles. They are composed of quarks and electrons. So when hydrogen and oxygen react to form water, it's just a rearrangement of the components of the atoms. There's nothing metaphysical about it, and the widespread success of quantum mechanics in predicting the properties of atoms and molecules, to a very high degree of accuracy, is in my view extremely strong evidence of this.

Also worth noting:

Hydrogen is not inherently flammable, as evidenced by the fact that the Sun is not on fire. Hydrogen is flammable in Earth's atmosphere because it reacts exothermically with oxygen.

Water is in fact quite a reactive molecule, although the surface of the Earth has been so saturated with water for billions of years that there's not much, if anything, left in nature that water reacts with strongly enough to generate flames.

There are plenty of manmade substances that burn with water, though. An increasingly common example is lithium metal, which can form inside of a malfunctioning lithium ion battery. Don't ever pour water on a lithium battery fire!

The boiling points that you give are for molecular hydrogen and oxygen, H2 and O2, and are not inherent properties of the atoms. An interesting illustration of this fact is that ozone, O3, is also composed only of oxygen atoms, but has a boiling point over 100 F higher than that of O2.

left all the best stuff for those last two footnotes!