What I Got Wrong About Lockdowns

Last March, I strongly advocated strict stay-at-home orders (aka "lockdowns") throughout most of the United States. When they said "two weeks to bend the curve," I immediately demanded extensions. When those extensions were granted, I cheered. When states began reopening in May, before meeting the benchmarks I (and the CDC) had set, I was profoundly disappointed.

Here is the basic pro-lockdown argument that I made:

Left unchecked, covid would have infected and killed something like 1 million Americans.

Lockdowns lasting 2-5 months (long enough to suppress the virus) would drastically reduce covid's spread, saving several hundred thousand Americans.

The likely benefit of saving several hundred thousand Americans (even mostly elderly Americans) was greater than the (likely catastrophic) economic cost.

Therefore, we should impose lockdowns.

Many people disagreed with me.

At the time, at least in my Facebook circles, there were two main arguments against lockdowns:

~1. (Not-1) Covid isn't very deadly, and will not kill more than 100,000 Americans in total. (The exact number used varied, a lot, but was most often between 50,000 and 100,000, because flu kills around that many Americans in a severe flu season.)

~3. (Not-3) Even if covid is going to kill a huge number of Americans, the economic costs of saving all those Americans will be so high that it won't be worth it.

~3a. (Not-3, variant) Even if covid is going to kill a huge number of Americans, lockdowns will also cause a huge number of Americans to die (from suicide, untreated medical crises, et cetera), erasing the benefits of suppressing the virus.

Basically: covid isn't that bad to begin with, and, even if it is, the lockdown cure is worse than the disease.

I am comfortable saying today that that those counter-arguments were wrong.

Covid turned out to be pretty deadly. In March 2020, I wrote, "Under ideal circumstances, the covid virus appears to kill about 0.6% of the people it infects." I cited evidence that covid was likely to infect between 20% and 60% of Americans before natural herd immunity kicked in, causing between 400,000 and 1,200,000 deaths.

That seems to have been about right. The best estimates today now place covid's fatality rate between 0.5% and 0.8%. Covid has killed 500,000 Americans so far, and it looks like it will kill a grand total somewhere between 600,000 and 700,000 when all's said and done. The end, when it comes, won't be from natural herd immunity, but from vaccines, which the Trump Administration and American industry produced with miraculous speed. If not for Trump's warp-speed vaccine development, we probably would be staring down the barrel of a million or so dead -- and even that's pretty close to ideal, because covid turned out to have a higher herd immunity threshold. Somehow, our medical system was able to hold together and never quite ran out of hospital beds (which would have caused far more deaths).

Meanwhile, the economic damage was bad... but it wasn't nearly as bad as I expected. I wrote last year:

Let’s accept that, regardless of what we do, pandemic makes major recession inevitable. People will die, supply chains collapse, consumer spending will vanish, it’s a nightmare. So let’s say, with... moderate measures... we lose 10% of GDP next year. (That’s several times larger than the Great Recession.) $2 trillion vanished in goods and services, taken from all of us, especially the poorest.

Let’s then assume that taking extreme measures makes things twice as bad. We lose 20% of GDP. It’s three years of the Great Depression all packed into one hell year. $4 trillion gone.

If those assumptions are true (and they’re not — they are at best in the ballpark), then it means that our additional safety measures need to save at least ($2 trillion / $9 million =) 222,000 American lives in order to be economically “worth it”.

None of that happened. My (deliberately pessimistic) expectations were not in the ballpark.

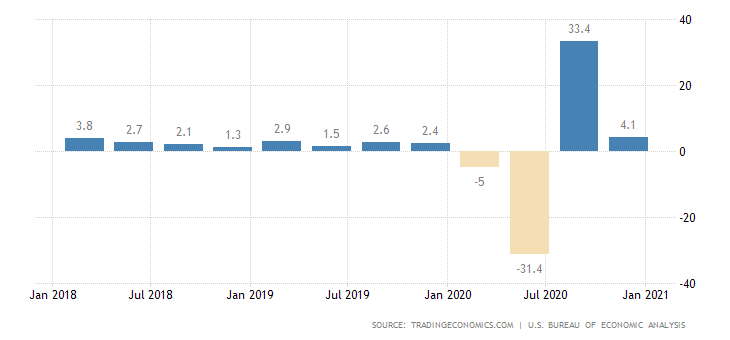

In Q2 2020, the economy shrank by an oh-my-God-my-stomach-just-dropped-into-the-second-subbasement rate of 7.85% (31% annualized). At that moment, it did look like the lockdowns had perhaps brought about an economic apocalypse. There had never been a GDP number that bad ever. Even the Great Depression didn't hit that hard in a single quarter. But, in Q3 2020, the economy rebounded, growing 8.35% (33% annualized) -- the best GDP growth number in history.

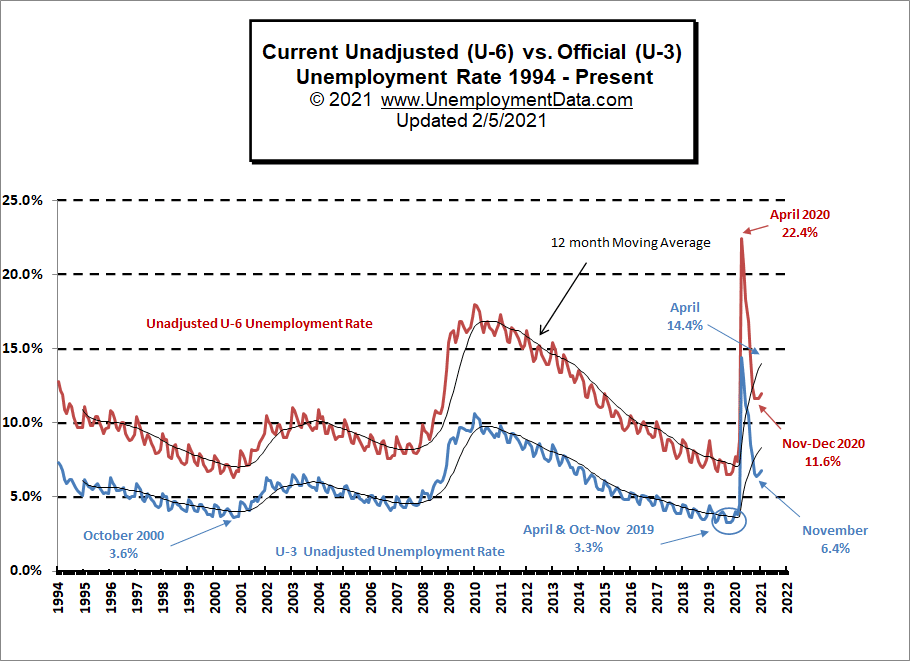

The United States ended up coming through 2020 with a 3.5% loss in GDP. That's still a terrible economic shock -- not as bad as the Great Recession, but worse than anything else since the Oil Crisis Recession. The way our bailouts favored large corporate consolidation while ma-and-pa stores got wiped out was a disaster we'll spend years fixing -- too late to bring back the ma-and-pa stores ruined in the process. But it was not a depression-level event. Here's U.S. unemployment (both the "official" U-3 and the "comprehensive" U-6 measures):

Unemployment of 6.4% is, again, real bad. I think Republicans were very wrong to accuse Democrats of making the economic pain worse to harm President Trump... but, if I looked at this chart without knowing anything else, I might very well ask God Almighty why He decided to destroy the economy at precisely the right moment to weaken President Trump's re-election campaign. Nevertheless, after months of recovery, unemployment today is where it was in 2013 and most of the 1980s -- not great, not terrible.

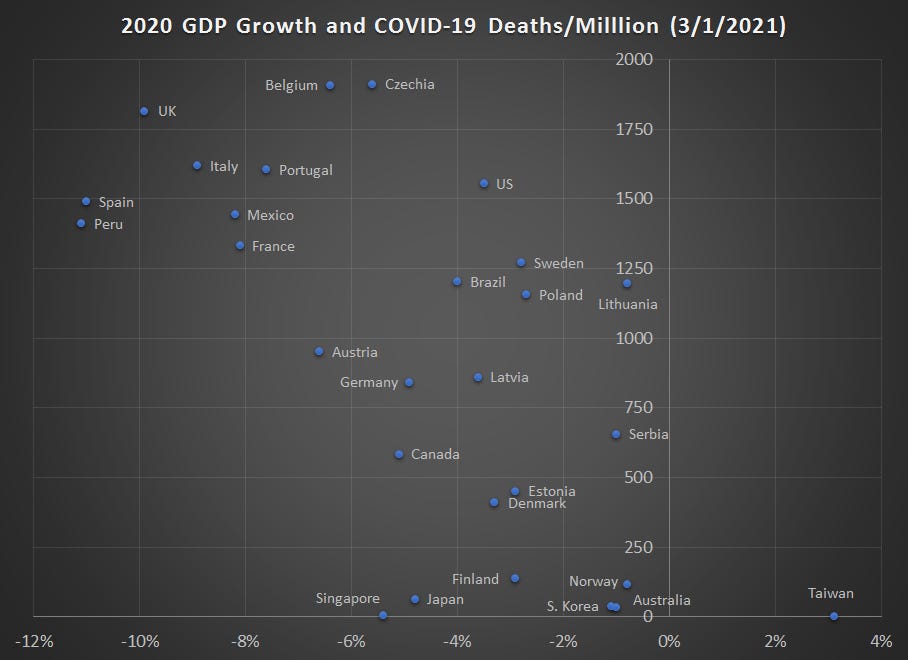

Could we have done better if we hadn't had a national wave of lockdowns? Maybe a little better, but probably not. Lockdown opponents rallied around Sweden as a (relatively) shining example of how to stay open in a pandemic, arguing that Sweden would build up herd immunity and come out the other side with a much better economy than all of us lockdowners.

But Sweden ended up down 2.2% of GDP over the course of 2020. That's a bit better than us, but not enormously, and worse than some countries with tighter lockdowns than we had. Lithuania's lockdown was much tighter and more comprehensive than the average American lockdown, but their economy lost only 1% of GDP in 2020.

Here's a chart whose x-axis measures something pretty similar, for a broad range of countries:

Do you see a strong correlation between "tightness of lockdown" and "amount of economic damage"? Just eyeballing it, I don't. And more thorough analysis (like the post this graph is from) doesn't uncover many clear trends here, either -- other than the obvious "being an island nation can really pay off, except the UK for some reason."

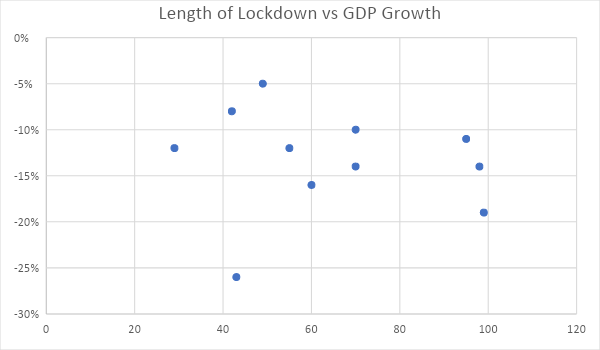

This chart, from here, I don't like quite as much, but it draws out the GDP growth / lockdown correlation a bit more clearly:

Shorter lockdowns don't have any obvious GDP benefit.

Meanwhile, the epidemic of "deaths of despair" that was forecast by some lockdown skeptics just haven't materialized. Lyman Stone at the American Enterprise Institute has been fanatically tracking excess death counts for months, and what he keeps finding is (1) the vast proportion of excess deaths in 2020 were covid or undiagnosed covid or misdiagnosed covid, (2) the other excess deaths are correlated with covid outbreaks but not with lockdowns, and (3) an awful lot of people want to make the contrarian narrative work, but it just doesn't hold up to scrutiny. Some handy (if long) Twitter threads of his: 1, 2, 3, 4

So: covid did kill a whole bunch of people and -- although the pandemic caused a global recession -- lockdowns specifically seem to have only made the economy and non-covid mortality a little worse, if that.

Not bad! But this post isn't called "What I Got Right About Lockdowns." It's called "What I Got Wrong About Lockdowns." And it was a doozy.

The lockdowns don't seem to have saved very many lives.

This is unexpected. Pretty much the one thing everyone on all sides seemed to agree on back in March 2020 was that lockdowns were a brutal but effective method for controlling the virus. It's such a simple, obvious theory (so simple a 14-year-old girl thought of it!): keep people at home, they can't go around spreading germs, the virus dies out... or at least is slowed drastically. Who could argue against it? None of the lockdown skeptics I was talking to. In my 3-pronged argument for lockdowns, my other premises came under heavy fire, but I never had serious arguments about this one.

Yet, by early May, I was developing some doubts. I wrote then:

While we know quite a bit about the characteristics of the virus itself, we DON’T really know very much about the social dynamics of mitigation, lockdown, and so forth. Much of what we do know is derived from not-entirely-analogous situations from the flu pandemic of a hundred years ago — not the best data set.

Consider the famous Imperial College model... [It made] assumptions [about] how people would behave.

For example, they assumed that, if infected households were asked to quarantine, those households would reduce community contacts by 75% and that 50% of households would comply. They assumed that, under a broad stay-at-home order, everyone would reduce external contacts by 75% (while increasing internal contacts by 25%).

Are these numbers reasonable? They seem reasonable to me. Are they correct? …how could we possibly know? We’ve never done anything remotely like this in modern times. The paper certainly cites no sources. These are educated guesses about human behavior. And if you tweak these parameters just a twinge, it can make the difference...

So it’s quite possible that government mitigation efforts combined with people’s natural desire to stay home in the midst of an epidemic does a better job of reducing disease spread than the experts think. It’s also possible that the added benefits of legally-binding stay-at-home are smaller than we think they are. Either way, moving to a “Sweden model,” where the government issues strong recommendations and tightly enforces social distancing in public spaces, but does not actually make you stay home, might lead to fewer deaths than one would expect based on the virus’s lethality.

Lockdowns, according to the theory, save lives by reducing transmission. You impose a lockdown, then, a week, two weeks, maaaaybe four weeks later, with the transmission links cut off, positive tests start to fall. If lockdowns don't reduce cases in a significant, measurable way, then they can't reduce deaths. If they don't reduce deaths, then they are pointless.

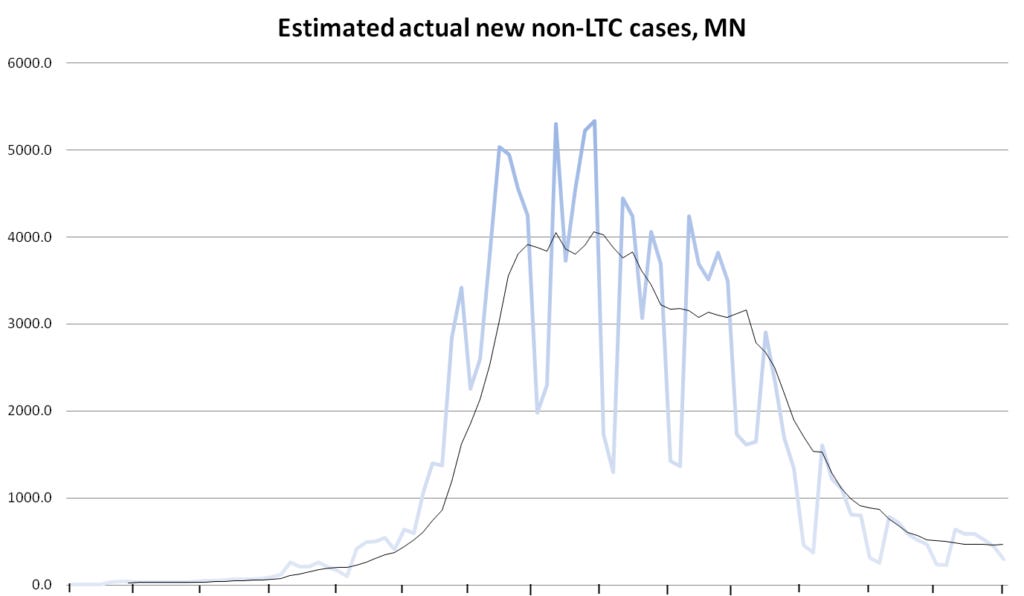

Here's a chart of Minnesota's (estimated) cases over a time period of exactly 14 weeks. (The data is from my covid weather reports last year.)

Look at this chart. Based on the theory above, when do you think Minnesota's lockdown started? When did it end?

Point at spots on the chart that make sense.

Remember: this chart covers 14 weeks. I added hash marks to the bottom to help you out.

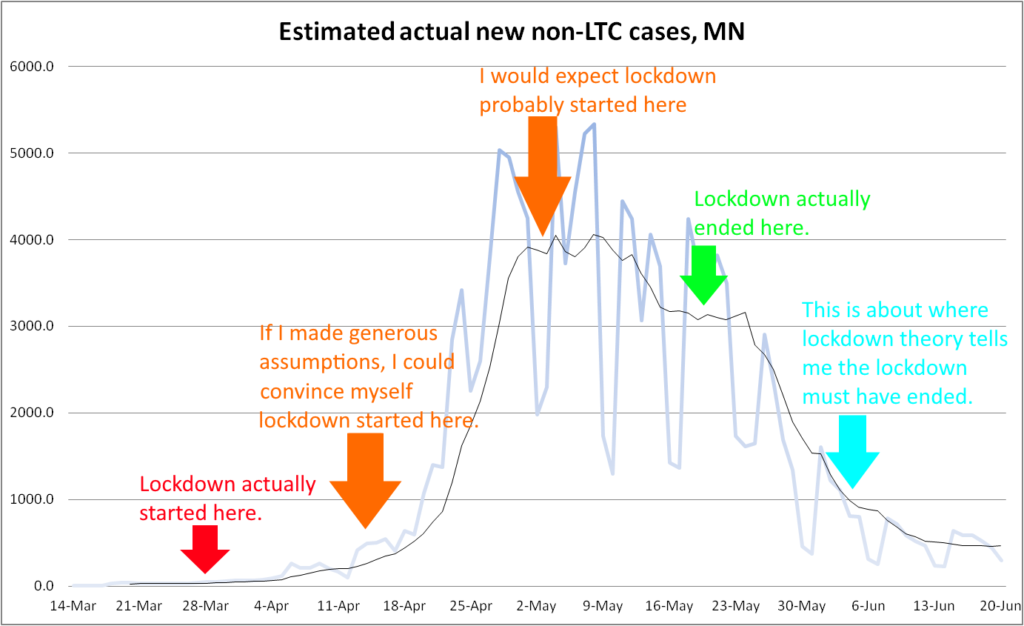

You got a spot picked out? Good. So do I. Here's the answer:

(No, seriously, you got some spots picked out? No peeking!)

Okay, here it is:

Lockdowns started on March 28th. Two to four weeks later, cases were not falling into suppression; they were skyrocketing. Then, we plateaued for four weeks, with a modest dip in the first week of May. Near the end of that plateau, we ended the lockdown... and then, instead of going through the roof as we expected, cases started to plummet instead.

This graph makes the whole idea of lockdowns look like a joke. I hate saying that, because I really can't overemphasize how intensely I favored lockdowns during precisely this time window. Given the same information, I'd probably even make the same decision again.

But we now have lots and lots of information not available to us in March 2020, and it does not make lockdowns look good.

The central problem is, Minnesota is not a fluke. You can make this basic chart with a lot of states. Sometimes, cases start falling before lockdowns could possibly have had an effect; sometimes, they start falling long after any lockdown effect was priced in. Either way, it's clear that, whatever caused case numbers to start falling, it wasn't lockdowns.

Marginally Compelling has examined a couple of paradigm cases -- Florida and New York -- in some detail, and, while the full post is subscribers-only, there's a good summary on Twitter. Lyman Stone was showing how lockdowns fell short in Europe way back in late April 2020. The passionately anti-lockdown (and not always reliable) AIER has a roundup of scientific studies that indicate lockdowns were ineffective, and/or that pro-lockdown studies made incorrect assumptions.

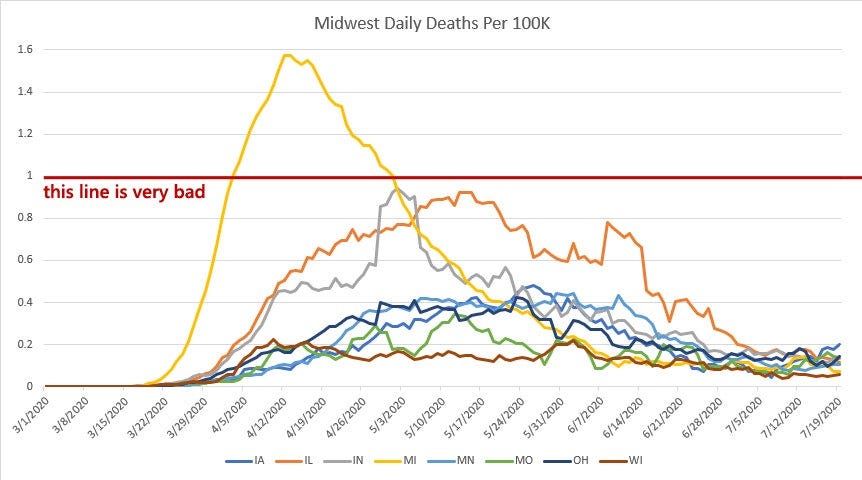

Another, easier way of looking at it is to just compare states that did lockdowns to states that did not do lockdowns, or did shorter lockdowns. Is there a consistent, meaningful difference between how more restrictive states weathered any given wave of covid, compared to their demographically-and-geographically-similar neighbors who were less restrictive? Is there any apparent change in direction in any state based on its lockdown dates? Can you (correctly) pick out start and end dates for lockdowns in, say, half of them? If lockdown theory is even slightly right, the answer for all three should be an easy, obvious Yes.

But the answer is No:

That chart is from Marginally Compelling's very handy "Your State's Covid Numbers In Context," July Edition, a monthly newsletter where he just charts every state against every other state in each region. So if you didn't believe me from this chart, you are free to jump over there and look at 56 more charts (8 per month for 7 months) until you are convinced that lockdowns have no visible impact on cases or deaths -- and are therefore useless.

As Marginally wrote, lockdown represents "the SimCity version of government, where dialing up the lockdown policies dials down the viral infections." It feels like it should work. It feels like doing something against a horrifying pandemic that has claimed far too many lives. But it doesn't appear to actually help, and wishing really hard that your state's covid lockdown will work if you personally just comply hard enough with it... well, that doesn't help, either.

This doesn't mean that all covid interventions are useless. You should wear a mask, regardless of whether anyone forces you to or not. Masks seem to work. (But state & municipal mask mandates evidently do not: check those state charts again.) Regulations limiting restaurant capacity still strike me as probably a good idea, although I haven't looked at the data in months and could be wrong. Large, dense, indoor gatherings of strangers, like concerts, are still a terrible idea, and states are still right to ban them. (Churches can and should open with low density and appropriate precautions.) When hospital capacity was near its limit, lockdowns themselves don't seem to have done much to control spread, but a closely related factor -- fear -- appears to have helped. Public authorities on the brink of a hospital crisis are probably smart to spread fear of what that would look like.

Yet the best interventions -- the ones that can actually get case loads down to Taiwan levels so everyone can return to normal -- appear to be (1) closing your borders to prevent initial epidemic "seeding" (ideally, you want to be an island nation), and then (2) aggressively testing, tracing, and isolating cases so the disease never gets out of control.

Once the disease does get out of control, your best bet seems to be internal border controls, where you deploy troops to seal off out-of-control parts of the country to control the damage -- something we, unfortunately, never seriously contemplated in the United States, aside from a handful of unserious attempts imposed to score political points, far too late to control the virus. But Finland did it, with some apparent success.

Once you've let the disease get out of control in an area, though, there seems to be no way back except (3) Wuhan-style lockdowns, where you weld people into their homes and disappear the violators, or (4) herd immunity. At least, I can't think of a free country that successfully moved from epidemic back to containment.

("But New Zealand!" New Zealand closed its borders when there were 28 total cases, zero deaths, and test positivity rates low enough to be confident there actually were only 28 cases in the country. Australia was only a couple ticks behind them. Covid was never out of control in either country. Compare: by the time the United States started locking down, on March 19th, we had an estimated half-million cases in circulation, our testing was still trash, and thousands of people who would ultimately die of the virus already had it.)

The disease got out of control in the United States way the heck back in February 2020, back when our entire testing apparatus was on fire, then-candidate Biden was calling President Trump a xenophobe for Trump's (good but overly timid) Wuhan travel ban, and we were being told to worry about anti-Asian racism and the flu even more than we were being told to worry about the virus.

Once that happened, it seems to be the case that most of our half-million-plus deaths were more or less inevitable. Our saving grace has been Operation Warp Speed and the most rapidly-deployed vaccines in history. (It is sheer lunacy that we delayed approval of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine until nearly March so the FDA could dot all the i's on the application form, and absolute crazy-pants that we haven't approved AstraZeneca... but that's another blog post.) The vaccines will end the pandemic and save hundreds of thousands of Americans' lives over the course of 2021.

Which, unfortunately, is a lot more than we can say for the lockdowns of 2020.