TRUMP!: What Now? …A New Party (3 of 3)

If other men choose to go upon all fours, I choose to stand erect, as God designed every man to stand. If, practically falsifying its heaven-attested principles, this nation denounces me for refusing to imitate its example, then, adhering all the more tenaciously to those principles, I will not cease to rebuke it for its guilty inconsistency. Numerically, the contest may be an unequal one, for the time being; but the author of liberty and the source of justice, the adorable God, is more than multitudinous, and he will defend the right. My crime is that I will not go with the multitude to do evil.

--William Lloyd Garrison, abolitionist, in an 1854 speech (h/t Neil Stevens)

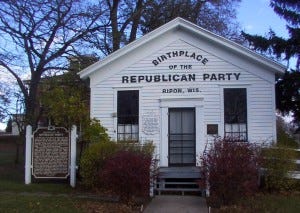

In 1854, sixteen brave men killed the intolerable Whig Party by forming the Republican Party. Perhaps it's time to do it again.

Donald Trump is the presumptive nominee of the Republican party.

On Tuesday, we discussed how this happened. Today, we have to decide: what are we going to do about it?

This is the third and final part of a three-part series. The first part deals with the fight from here to the convention. The second part deals with the 2016 election. This final part looks beyond 2016 to a new conservative future.

This is the longest entry in the series. It is also the most important. I do not know how to make it shorter.

November 9th and Beyond: Conservatism Without Republicans

I don't think we can stay in the Republican Party.

It's not just that a chunk of us fell to the Trump Delusion. I can write that off. It was a mass fever. It was rational anger that got out of control. It was because of all that free media exposure. It was a cult of personality. It was excessive direct democracy -- and so on and so on. I know all the excuses, and I've made a good number of them myself. I am even able to just admit that a good chunk of my co-partisans (as many as one-third, perhaps!) are just basically politically corrupt, either willfully ignorant or openly malicious or both, and nevertheless remain in a tense but workable alliance of convenience with them.

No, what's really beyond the pale is how the Republican Party's power-brokers have reacted. Our media apparatus, from Hannity to Limbaugh to Breitbart, was far too willing to not only give Trump a platform, but promote his anti-conservative candidacy by every available means. Many stood against the Trump tidal wave, and stand against it even now... but not nearly enough.

Even worse was our ruling class. These are the rich guys who live in the Beltway or the Acela Corridor and set most of the party's agenda. They claim every year that, deep down, they really are conservative, right down the line... but they want to "compromise" because they are concerned about "electability" and "expanding the map". Oddly, their "compromises" always take the form of surrender on social issues, from abortion to immigration, while standing fast -- no matter the political cost! -- on tax rates for the rich and big corporations. This year, our Republican overlords had a chance to prove their "conservative" bona fides. They were faced with a choice. On the one hand, Ted Cruz, an unpopular, disliked, and personally irritating senator who, though he polled middlingly against Hillary Clinton, would also have been the first consistently conservative nominee since Reagan. On the other hand, Donald Trump, a violent, racist, unelectable, lying, adulterous thug without a principle in his body, whom the general electorate likes about as much as they like scrotal cancer. Any conservative who cares about electability and the Republican brand would have picked Cruz -- reluctantly, perhaps, but, against Trump, there was no question. At worst, a conservative might have declined to choose at all.

Yet the Republican ruling class picked Trump. They didn't pick him by inaction, either: they came right out and said they'd rather have Trump than Cruz. Now that Trump is the presumptive nominee, they have rolled over and started asking for back-scratches from Casa Trump. If they're "conservative," I don't know what "conservative" means anymore.

It's not like this is the first time they've betrayed us, either.

I suppose, since I keep talking about "we" and "us," I had better state who "us" is, for the record. I think you already know whom I'm talking about, dear reader, and I'm not sure there's a name for us anymore now that the "conservative" brand has been sullied.

We're pro-life, pro-family, and pro-freedom.

We distrust Big Government, on the whole, but we acknowledge there's a place for it in the social safety net, and we're coming to distrust Big Business just as much.

We believe that the well-being of this country is in the hands of local institutions that make up the fabric of civil society: community volunteer groups, churches, mutual aid societies, guilds, local governments, and families.

Most of us are Christian; a surprising number of us are Catholic.

We care first and foremost about social justice, but the so-called "social justice warriors" who have taken over the "social justice" label lately do not seem to have the first clue what social justice is actually about, and lots of them truly hate us and what we stand for. This leaves us without a label.

In another time, we might have been labeled "social conservatives" instead. However, in contemporary discourse, that label has become very narrow. It now refers to just two issues (abortion and LGBT questions), and so it, too, doesn't really capture who we are or what we're about. For example, plenty of Trump people are opposed to abortion and are way angrier about transsexuals than I am, so they are labeled "socially conservative"... but they believe and act in ways totally alien to me, telling pregnant women "it's your problem now; you should have kept your legs shut" and screaming slurs at trans* people whether they're in a bathroom or not. That's not us. In fact, those kinds of "social conservatives" horrify us. So "social conservative" isn't the right label for us, either.

Because of the way political coalitions have shaped up since the Reagan Revolution, we've gone along, sometimes reluctantly, sometimes not, with many of the stranger policy prescriptions in the Republican Party -- let's cut taxes on the rich! again! even though our own party doesn't really want to! let's let monopolies seize control of the Internet! why not! -- because the Republican Party promised that, if we had their back on the money stuff, they'd have ours when the time came.

Surprise! They didn't.

I've been griping for years about how the GOP left pro-life voters with table scraps after four years of unitary control of Washington. And hardcore pro-lifers were hardly the only group among us who got burned by the Republicans' spending-entitlements-and-nationalization binge of 2002-2006. But we don't need to go back years -- it's been not even a month since our "allies" in the business community turned against religious freedom in Georgia, and convinced Republican Gov. Nathan Deal to kill a bill that would have protected Christian businessmen from being forced to violate their consciences. That wasn't even the first religious freedom bill our fellow Republicans stabbed in the back.

And then, in the final treachery, when faced with one man who lived up to the party's espoused principles and another man who openly defied nearly all of them... our Republican leaders, however reluctantly, picked the bad guy. Then they demanded the rest of us surrender to him. (They really wanted Kasich, who followed the social-liberal fiscal-conservative model to a T, but, when that was off the table and they were confronted by the possibility of picking a down-the-line social conservative for the first time in 32 years... they took Trump instead.)

As I said last night: Trump will pass, but his voters will still be the Republican base, and those establishment figures -- who have been using me for a while, and who are increasingly hostile to the things I stand for -- will still be the Republican leadership. This isn’t just a 2016 problem. So how can I ever call myself a Republican again?

It is too late in this election cycle for us in the peanut gallery to do anything about 2016. We fought with everything we had for the soul of the Republican Party... and we lost. The rulers sided with our rivals, and now we're out of time, money, and ammo. We must hope that the Libertarian Party and #NeverTrump are able to organize something, to give us someplace where we can ride out the storm. We'll all find our own ways of getting through the 2016 hellscape, as we discussed in Part 2.

But 2016 is not the last election there will ever be.

I think it is time to look ahead to 2018, 2020, and beyond. I think it is time to wave a fond goodbye to a Republican Party that has been our home for a generation -- Peggy Noonan is right to mark this as a sad, even tragic, moment -- and I think it is time for us to strike out into the wilderness... where we can build something new.

How to Tame a Political Wilderness

Of course, if you go out into the wilderness without a map or any idea what you're doing, you're going to get eaten by lions. (Or something. Do we have lions in America? I don't really know anything about the wilderness. No, I was not a great Boy Scout.) It has been 160 years since anyone built a new, successful political party in these United States. Nobody alive knows how to do it.

Progressives might say that we should just head out there with no plan and figure out for ourselves a brand new way of doing politics, one that's better than any that has ever been done before. But we are followers of G.K. Chesterton, at heart, and we know things are the way they are for a reason. Especially if they stay that way for a century and a half.

So let's time travel back to the last wholesale restructuring of the American political parties, in the 1850s, see how it came about, and take what lessons we can from their story.

(If history bores you, you can skip this section and go straight to the next part.)

RESOLVED: That we invite the affiliation and cooperation of the men of all parties, however differing from us in other respects, in support of the principles herein declared; and, believing that the spirit of our institutions as well as the Constitution of our country guarantees liberty of conscience and equality of rights among citizens, we oppose all legislation impairing their security.

--Closing of the first National Platform of the Republican Party, 1856

On March 3rd, 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed the Senate with the bipartisan support of Democrats and Southern Whigs. The Act repealed the Missouri Compromise and gave the slave power an opportunity to expand its reach into once-free Northern territories.

Anti-slavery voters -- who had supported the Whigs as the best available bulwark against slavery -- were outraged. A party that not only failed to block such a poisonous bill, but actually saw a large portion of its membership openly support it, could no longer be worthy of their support. Perhaps if this had been an isolated incident, they could have reconciled with their party, but it was not: anti-slavery voters had been forced for years to swallow concession after intolerable concession to the interests of slavers. Kansas-Nebraska was not the first blow, but the final straw.

In Ripon, Wisconsin, on March 20th, the Whig town committee met with the Free Soil town committee (with some town Democrats in attendance) to discuss the crisis. There were 16 people in attendance, and this was their second such meeting: anti-slavery representatives of all three parties had met one month earlier and resolved to take drastic action if the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed the Senate. Now that it had passed, the politicians of Ripon followed through without hesitation: that night, the Whig and Free Soil town committees voted to dissolve. A committee of five – 3 Whigs, 1 Free Soiler, and 1 Democrat – was established to create a new political party, which would stand for freedom and human dignity against the vast power of slaveowners.

By May, with similar town committees springing up all over the North, the party had the support of a number of Whig and Free Soil Congressmen. It had also gained an unofficial name along the way: it was now known, in enthusiastic ex-Whig newspapers across the land, as the Republican Party.

It took two years for the nascent party to become fully organized. The first Republican state convention, organized and promoted by anti-slavery newspapers, met in Michigan that July, adopted the first statewide Republican platform, and nominated the first statewide candidates. Five other states followed suit that year, in time for the 1854 elections, but it was not until 1855 that the Republican Party was well-established throughout the North, with some degree of organization in every state. There was no national organization until the first national convention, held in 1856 at Philadelphia and open to anyone who supported the party's ideals.

At times, as in Ripon, the local Whig party cooperated in the formation of the new party and was immediately absorbed. At other times, as in New York, the Whigs clung to life for a while -- it took the influence of the powerful politician William Seward (ex-governor, sitting Whig Senator, presidential hopeful) to merge the two parties, which they finally did on September 26th, 1855.

The Whigs disintegrated. As the principled anti-slavery faction departed to join the new Republican Party, a separate, thuggish, populist, nativist faction (stop me when you've heard this one) was also leaving to form the cult-like Know-Nothing Party, along with many like-minded Democrats. (The Know-Nothing Party's official name was the "American Party," because they wanted to make America great again by ridding it of "foreign" influences.) Between the Republicans and the Know-Nothings, there just wasn't anyone left to be a Whig.

The Know-Nothings found strong support throughout New England and the South (sound familiar?) and were, initially, even more successful than the Republicans:

Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that 'all men are created equal.' We now practically read it 'all men are created equal, except negroes.' When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read 'all men are created equal, except negroes and foreigners and Catholics.' When it comes to that I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty — to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.

--Abraham Lincoln, private letter, 24 August 1855

The Whigs survived 1854 partly because their opposition parties simply hadn't had enough time to organize as credible political forces, but, by the presidential election of 1856, the Whig Party was a third party with minuscule representation in Congress and no presidential candidate. By 1858, the Whigs were totally extinct.

The Republicans and the Know-Nothings competed closely in the 1856 presidential election, but the Republicans finished well ahead of the Know-Nothings. After the Know-Nothings subsequently drove Nathaniel P. Banks, one of their most prominent members, to join the Republicans, partly because of the Know-Nothings' hardline stance on immigration (really, I am not making up all the parallels to today!), Know-Nothing support in the North began to cave, and they never recovered. In 1860, the Republicans swept every Northern state, winning clear majorities in 15 states... thus the electoral college, with those states alone. The Republican Party had disemboweled and replaced the Whig Party as America's second great political party.

(I owe a considerable debt to The Formation of the Republican Party as a National Political Organization, by Dr. Gordon S.P. Kleeburg, published in 1911 and available here. Also Wikipedia. And to Mr. Hoverson, who taught my A.P. U.S. History class many years ago.)

Back to the Future

I have no interest in building yet another utopian fringe third-party that never wins an election. America has plenty of those, from the Constitution Party on the Right to the Green Party on the Left. There will always be two and only two major parties in America. If our new party can't disembowel one of the existing major parties and take its place within a dozen years, then there's no point.

The Republican Party of 1854-1860 provides us with a blueprint for doing just that. Here are the lessons I took from that history.

1. A new party must draw sizable numbers of voters from both existing major parties. This triggers a political realignment. If you only draw voters from one of the existing parties, all you do is shrink that party and make it easier for the opposition to win. You can be predominantly from one party -- the Ripon Republicans, after all, put 3 Whigs on their 5-person founding committee, and most Republicans, nationwide, were ex-Whigs -- but if you can't draw a big chunk from independents and the opposition party to plug the holes you made in your coalition by leaving the original party, you simply can't build a coalition that'll win 50%+1 of the electoral college.

2. A new party starts at the grassroots. It was the sudden, near-simultaneous formation of Republican town committees in towns across the North that made the Republican Party possible. They were the party's hands and feet. For a while, before the national organization formed, they were its head and heart, too. Without spontaneous, widespread mass political action -- and, yes, that meant showing up to meetings, not just putting up a hashtag on 1850s Facebook -- our new party won't come to life.

3. However, a new party needs major support from existing elites. Local grassroots political committees form and break up all the time. Wikipedia lists dozens of American political parties that are active right this minute, and there have been hundreds more scattered throughout American history. Nearly all of them start out with a dream of major-party status. Only a handful have ever achieved it, and none has in over a century. The Republican movement grew as it did because it wasn't just sixteen angry guys in a schoolhouse: local party officials across the Midwest defected en masse from their current organizations to join the new one; newspapers and newspapermen from the Detroit Free Democrat to Horace Greeley himself aggressively waved the flag for the new party; sitting Congressmen openly embraced it; and presidential hopefuls like William Seward adopted it. Without that widespread elite support, you're just another Rent Is Too Damn High Party controlling some minor city council somewhere in upstate Vermont.

4. The new party must be animated by a massively appealing central issue (or two) which the two existing major parties have given short shrift. If you're asking people to abandon their current political affiliation to throw in with a brand new party, you'd better give them a darn good reason. You need to be backing a policy that they really want... and which they can't find in the mainstream parties. For the early Republican Party, the central issue was opposition to the expansion of slavery, and, to a lesser extent, support for national infrastructure spending.

5. The new party must remain flexible on most everything other than its central issues. The current Republican Party platform is 56 pages long and takes clear, binding positions on literally hundreds of different issues -- perhaps thousands, depending on how you count. The current Democratic Party platform is similar.

By contrast, the original Republican Party platform is one page long, and takes positions on exactly two issues: they oppose the expansion of slavery (especially in Kansas and Nebraska), and they support national infrastructure spending. (...okay, they also condemn polygamy, briefly.) This narrow focus on their core issues allowed the Republicans to remain attractive to everyone: you could disagree with each other on tax policy or the Ostend Manifesto or whatever, but, as long as you voted against the pro-slavery Leocompton Constitution and voted for the Transcontinental Railroad, you could still be a Republican.

6. The new party will not just emerge one night; it is born of many long discussions with all sorts of people and careful measurement of the electorate. The man who led all those officials into a schoolhouse to birth the GOP, Alvan Bovay, had been talking to other people around the country about a new party for a while. He wasn't alone. Although the mass defections from the Whigs were spontaneous, that energy was able to be harnessed into a new party thanks to years of quiet discussion, in which politically-minded people across the country gauged what might and might not work in a new party. When the Kansas-Nebraska Act finally came to light the fire, people around the country were ready with the bold Republican answer to widespread Whig dissatisfaction.

7. The new party can only emerge in a time of political instability, when dissatisfaction in both parties is running very high. This seems like an obvious corollary to what's already been said, but if you plan to get a lot of people to defect to your party, at least some of them will have to be unhappy enough with their own party to be on the lookout for another opportunity. It makes 2016 an opportune moment for a new party: dissatisfaction with the parties has been running historically high for several years now, and the Trump/Clinton nominations have alienated an incredible number of voters on both sides.

8. The new party must show regional strength before it can be seen as nationally viable. The early Republican Party showed great strength in the Midwest, immediately becoming a major political player in a handful of states. Only after soundly destroying the Whigs in those territories was the party able to expand in New England (which was caught up in the Know-Nothing wave) and the Mid-Atlantic. And it was not until after the Civil War and emancipation that Republicans saw their first wins in the South.

9. The new party's ascent to power isn't going to be clean. In 1854, the Know-Nothings roundly beat the Republicans. In 1856, the Know-Nothings arguably spoiled the election and handed it to the Democrats. In 1858, the Dred Scott decision made it seem that the Republicans had been utterly vanquished, and that slavery would expand forever. In 1860, the Republicans won the presidency in a four-way race with just 39% of the vote. In 1861, civil war broke out. After the war, Republicans reigned for a generation.

Point is, in a first-past-the-post electoral system, weird stuff happens when a third party shows up on the scene and starts seriously contending against the two established parties. Sometimes you win because the chaos benefits you, and sometimes you lose because the chaos benefits someone else. Your job is to just keep chomping away at your predecessors until you win.

I can hear you saying right now, "This is all well and good, James, but how do these history lessons help us out today? What's the plan?"

I'm glad you asked.

The Plan: Boring Version

Our new party will not be active in 2016; it's just too late for us to enter the race. This gives us an opportunity to spend this year planning and coordinating. An important element of this will be securing early elite support, particularly among current Republicans (because the membership of our new party will be predominantly ex-Republican). If Sen. Ben Sasse, Rep. Justin Amash, Matt Walsh, First Things, and the National Review express enthusiasm about our project by the end of this year, then we're on the right track. If nobody's biting... then this whole thing is probably not happening.

In 2017, we should be securing volunteers to serve as party officers in every state (except, perhaps, in New England, where it seems pointless). A few local Republican party organizations (and perhaps even some Democratic organizations) should be willing to leave their current party and join us. (State parties will follow much later.) If we don't start seeing support from ideologically sympathetic media and bloggers, too, then we're dead on the vine.

In 2018, our party should propose competitive candidate slates, both for federal and state offices, in at least ten states, and we should win at least ten seats in Congress. This should be possible regardless of who is in the White House. Meanwhile, the first national convention should be held in 2018, to establish a standing, elected governing body for our party and to begin preparations for the 2020 presidential election.

In 2020, we should nominate a presidential candidate and be competitive in that race.

By 2024, we should win the White House.

If any of this doesn't happen, it calls into question our viability.

The Plan: Interesting Version

Blah blah blah, enough with the nuts-and-bolts benchmarks, James! Tell us the plan. What's our new party going to be about? Who's going to join it?

The truth is, I don't know yet. In the coming months, I want to talk to people -- a lot of people, from all sorts of backgrounds -- about their frustrations with the current party system, their most important issues, and their non-negotiables. I hope, if you are interested in this project, you'll also start talking to people you know -- whether they're U.S. Senators or first-generation Vietnamese immigrants, party chairmen or people at Walmart -- and share what you hear.

Once we get a clearer picture of the electorate, a picture that goes deeper than the "red vs. blue" simplification we've been living under for the past fifteen years, then (and only then) we will be able to identify a broad, dissatisfied coalition and the platform that can bind us together.

Still, I'd be lying if I said I hadn't given some thought to what our new party might look like. Of course I've had some ideas about the new coalition of my dreams. I've dropped some hints already, but let me lay my cards on the table and share the concept I've been toying with for the past few days:

I'd like to establish a party whose first principle is a commitment to the inherent dignity of the human person: at conception, at birth, in childhood, in college, in poverty, in sickness, in prison, in a refugee camp, in marriage, in the workplace, at church, in parenthood, in our country, in foreign lands, in old age, in natural death. Wherever there are human beings in need, we will support them, and we will protect their lives, their liberty, their property, and their well-being through wise, honest laws and a strong social safety net.

This plank embraces a consistent ethic of life, rooted in the principles of social justice. It would allow the two "sides" of Christian electoral politics -- the anti-abortion conservatives and the anti-poverty liberals -- to finally make common cause together.

The second principle I have in mind for our party is broad opposition to the giant, impersonal, inhuman entities that increasingly rule our modern world: Big Business and Big Government. These huge entities are crushing the life out of our society, in many different ways.

On the business side, this plank encourages small business and local institutions. For example, a progressive corporate tax code might be instated to penalize corporations that grow too large, incentivizing them to break up into smaller, more human, companies. This plank also prefers personal ownership of companies rather than shareholder governance, and hopes for the establishment of guilds and unions to support workers in all circumstances. (Chestertonians may recognize this as an approximate implementation of distributism.)

On the government side, this plank embraces the "forgotten" social justice principle of subsidiarity, where local governments are the most important part of the social safety net, state governments are the backstop, and the national government allows them to each solve problems in their own way. By all means, let's have some form of universal health care -- but let's do it at the state level, without forcing it on states that prefer a different system. By all means, let's support marriage -- but allow each state to find its own way of making marriage work. Only truly national problems, like war and global climate change, should be addressed by the national government. Often, we will disagree with how other states and cities handle things; sometimes, we will find their solutions upsetting, even unjust. But it's a big country, and, as Alexis de Tocqueville observed, the spirit of democratic self-government withers without local rule and local diversity:

The New Englander is attached to his township because it is strong and independent; he has an interest in it because he shares in its management; he loves it because he has no reason to complain of his lot; he invests his ambition and his future in it; in the restricted sphere within his scope, he learns to rule society; he gets to know those formalities without which freedom can advance only through revolutions, and becoming imbued with their spirit, develops a taste for order, understands the harmony of powers, and in the end accumulates clear, practical ideas about the nature of his duties and the extent of his rights.

--De Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Chapter 5

Taken together, this second plank draws together the small-government "conservatarian" Right to come together with the anti-corporate Left.

So, it all comes down to two big ideas: human dignity, at every stage of life, and smaller, more humane institutions. If you agree on those big ideas, the rest is negotiable.

Imagining a New Coalition

Who would join this new party? Remember that this is all quite preliminary. We need to have a lot of conversations, still, to figure out whether these ideas are viable, or whether we need to go in a different direction. Still, in the interest of getting your imagination working, here is a first draft of how our new coalition might look, based on the platform above:

First, defectors from the Republicans.

I think the new party has tremendous potential to win over current Republicans throughout the Midwest and the West. These are the territories where Rick Santorum and Ted Cruz performed best, and cities in those regions were major sources of support for Ron Paul. Those people are all too likely right-wing to be presidential candidates in our new party (more's the pity), but I think their supporters will find much in common with our platform. Further West, you find a great many Mormons, who very much fit the profile of our new party.

Republican support in the West and Midwest would mean a great deal: the red states alone account for more than a third of the Republican Party's electoral votes in the 2012 election... with room to grow in the purple states. This would be the home region for our new party, just as the Midwest served as the home for the Republican Party in the 1850s, where we would win our first elections, supplant the Republicans, and grow into a national player.

Here's who isn't going to join our party: the Republican Party in the Northeast, from Vermont down to Delaware, is lost to us for at least another generation. They appear to be divided between outright supporters of the Know-Nothing Party the Trump campaign and the Wall Street Journal plutocrats who enabled them. The South, which also saw surprisingly strong support for the Trump campaign, may also be challenge, but not nearly so much as the Northeast.

From the Democrats, I think it's widely underestimated how much support there is among their rank-and-file for more life-affirming social justice policies. Many Democrats of my acquaintance, who are otherwise sympathetic, vote against Republicans simply because they hate and fear the plutocratic, pro-corporate policies of the Republican donor class, or because of the Republican donor class's hostility to private-sector unions, or because of the Republican donor class's enthusiasm about cutting welfare program as opposed to, say, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. However, our new party would jettison the plutocrats, which gives us far greater flexibility on economic policy than the Wall Street Journal editorial board would ever tolerate. This flexibility can (and hopefully will) bring in much support from socially conservative, fiscally liberal Democrats, particularly in the Midwest and West.

I am especially interested in attracting disaffected Sanders voters, who reject the bipartisan military-industrial complex embodied by Clinton and Boehner. It is an open question, though, how many of them would tolerate the religious liberty aspect of our human-dignity platform.

Republicans also have some problems with non-whites that the new party will not. Republicans, for instance, now have such abysmally bad branding among non-whites (and this will get worse with Trump) that it's hard to see how they could even consider supporting the party. They believe the Republican Party hates them at worst and is indifferent at best. With the rise of Trump, there's a good argument they're right! Beyond this, much of the opposition to the Republican Party in minority communities comes (once again) from the GOP's hardline stances on the function of government and the scope of welfare programs... on which many minority voters depend. If those stances are relaxed and channeled into a subsidiarity framework, where welfare programs begin to operate at a more local level, that presents at least an opening for our new party to court voters on whom the GOP has turned its back. I mean, guys, African-American voters are economic center-left moderates with social conservative instincts who distrust the kind of rapid change the radical Left looks for. But not many of them are going to vote for the party of the Southern Strategy, and very few indeed would consider the party of Trump.

Finally, I hope to bring many libertarian-minded voters into the fold. Subsidiarity is not the same thing as libertarianism, but it is compatible with libertarianism at the national level and far more willing to tolerate libertarianism at lower levels of government, compared our current system. This, presumably, is why so many Rerum Novarum-loving Catholics find themselves making common cause with libertarians so often already. (You couldn't throw a stone in the Ron Paul 2012 ground campaign without hitting a Catholic whose second choice was Santorum... including me!) Libertarians and libertarian-leaners aren't a huge group of Americans, but they could be a substantial boost to our coalition, and they skew young, which bodes well for the future.

Of course, this isn't a perfect party for anyone. Regardless of the platform we come up with, it won't be a perfect party -- not for you, not for me. No party is, except the fringe utopian parties that exist just to make their few constituents feel pure. I bite my tongue a lot in the GOP (seriously, guys? do we have to insist global climate change is a science conspiracy from top to bottom?), and I will still be biting my tongue in this new party, just on different issues. I am pretty sure, for example, that the coalition I am proposing would raise the minimum wage, and I personally don't believe we should have a minimum wage at all. Oh, well; bite my tongue. That's big-tent politics for you.

But our country will not rise or fall on the minimum wage. Our country will rise and fall on other issues, like life, liberty, and the rule of law. Right now, I do not believe that those issues have a real home in either party. If I can give them a home in a new major party, I'm willing to give up a few minor issues along the way.

My hope is that many people, from across the political spectrum, feel the same way -- enough that we can come together, take on, and take out one of the major parties. (Presumably the GOP.) With a new coalition that wins red and purple states in the West and Midwest, draws in the Rust Belt, makes modest inroads into the South, and wins that wild card Florida, winning the electoral college and the presidency in 2024 seems reasonable.

I guess we'll find out.

A Final Word

I am going way, way out on a limb in this post. My most recent post was hesitant to say who would be the 2016 Libertarian candidate for president, and yet here I am, the very next day, publishing a piece that predicts and then sketches out the rise of a new second party in U.S. politics -- in a fair amount of detail.

On the one hand, I find it difficult to see how anything else could happen, given the deep corruption of the Republicans. The idea of buddying up with the party of Trump, Preibus, Christie, and Kasich after 2016 gives me the heebie-jeebies, and I know I'm not alone. (I'm told that a recent Republican mailing went out that said the party must "unite or die." One prominent Republican wrote back, "I choose death.") People are burning their GOP registration cards left and right, and I have the sense that it isn't just our Twitter intelligentsia who are horrified at what our party has become. I know many of my Democrat friends feel the same horror about being in the Hillary Clinton/Debbie Wasserman Schultz party for the next four or eight or fifty years. How can the current party system possibly survive 2016?

On the other hand, I just tried to sketch out a momentous shift in American politics over the course of many years. I have a lot of trouble predicting what's going to happen next week. Perhaps there is some other path forward. Perhaps the #NeverTrump movement is already planning its return to the GOP fold after 2016. Perhaps they have some idea how they're going to deal with the party's demographic free-fall and surprisingly yuge Know-Nothing faction. Maybe there's just too much inertia in the party system today, and a new party can't follow the same road the Republicans took in the 1850s. Passions cool, and Trump and Clinton will begin to feel normal in the heat of the election, so maybe the will for change fades by the time we get to work on November 9th. Even if a new party is possible, a lot of things have to come together for a new major party to form: dissatisfaction in both parties, grassroots support, elite support, agreement on a platform, electoral success, huge amounts of political energy, and no small amount of plain old luck. So, if you were to take a bet out on our new party winning a single seat in 2018, much less the presidency in eight or twelve years, I'm thinking PaddyPower isn't going to give you great odds.

But Donald Trump is my party's nominee. What the hell else am I going to do for the next two years?

If you broadly agree with what I've articulated here, if you're a Republican suddenly looking for an alternative to Republicanism (or a Democrat looking for an escape from Clintonism), or you're just interested in where this goes, sign up for email updates. This is a special mailing list I am making just for the new party: you won't get anything except updates about this party, and that's assuming it goes anywhere at. You won't get blog updates or other spam.

Okay, looks like the subscription script isn't working. For now, click this link. I'll try and get the proper form fixed tonight.

Over the coming weeks and months, I'm going to talk to some people I know about this, including a few Republican elites, sound out interest, refine that platform proposal, and try to answer some of the many questions this post has introduced.

I'm also going to try to come up with a name for this thing! I can't just keep calling it the "New Party"! I tried "Localist Party" out on my wife last night, but she didn't think it had a good ring to it.

The comment boxes are open. You can also email me -- pretty sure my email is somewhere over there in the right column. I'd love to hear what you think about this, what your vision of the future might hold and how it differs from my vision, what you're hearing from others, what kind of platform refinements might expand the tent without compromising our core beliefs, and, heck, anything else on your mind.

And, seriously, if you have any name ideas, I'd love to hear 'em.

After opening with the rage of Garrison, I close, pensively, with de Tocqueville, who reminds us, appropriately:

Born under another sky, placed in the middle of an always-moving scene, himself driven by the irresistible torrent which sweeps along everything that surrounds him, the American has no time to tie himself to anything; he grows accustomed to naught but change, and concludes by viewing it as the natural state of man; he feels a need for it; even more, he loves it: for instability, instead of occurring to him in the form of disasters, seems to give birth to nothing around him but wonders.

--Alexis de Tocqueville, 1831