Stop Being An Idiot: You Can (and Should) Survive a Nuclear Attack

Forget seven decades of satire about civil defense drills drilling: in an actual nuclear attack, these kids probably won't die. Will yours? Unironically, now: DUCK AND COVER!

"When a man is convinced he's going to die tomorrow, he'll probably find a way to make it happen." –Guinan

In 2018, we once again live under a daily, credible threat of nuclear war. The threat has been growing for a long time now, and it shows every sign of accelerating. Fifteen years ago, a man my age could imagine that we'd solved the nuclear problem, that we'd only ever see mushroom clouds in science class and Fallout games. Today, imagining the next fifteen years in geopolitics without a nuclear bomb going off at some point is becoming something of an exercise in creative writing.

This is unfortunate. Any successful nuclear attack on any plausible target in the world would make 9/11 look like a garden party. Tens to hundreds of thousands of people would die.

But it would not be the end of the world. Even in the city targeted by the attack, the vast majority of people would survive. "But, James, after the bombs fall, the survivors will envy the dead! I've seen Deliverance!" Nonsense. In all likelihood, the vast majority of the survivors would go on to live out normal, rich, fulfilling lives and die in old age.

That is, if they don't get themselves killed by negligence, ignorance, and despair during the attack and its immediate aftermath.

This blog post is brought to you by this pretty good article by GQ Magazine about the recent nuclear false alarm in Hawaii. Specifically, this post is brought to you by the irrational fatalism of the Hawaiians in the article, and by the insanely dangerous things they did because they thought they were going to die and there was nothing they could do:

Becca went to the bathroom, came back. She did not think to retrieve the survival kit, which consists primarily of a transistor radio with possibly dead batteries in a Tupperware tub in the hall closet. She did not consider where best to shelter. She's a psychologist and reflexively thought in psychological terms: If this is real, she and her family were not going to survive it, and it could be real because Donald Trump is impulsive enough to spook North Korea into lobbing a missile at Hawaii. And if they were all going to die, she'd rather her children didn't do so screaming. She called them into the bedroom, piled them on the bed, and played, tickling and laughing and not saying anything about a missile.

***

Hans went out to the balcony. They live on the third floor, and when the rain falls in the right place at the right time, they can see the mountains rising up to meet a rainbow. He wondered, briefly, if Honolulu would look like The Day After, a television movie about a nuclear attack on a small Kansas town that 100 million people watched when it aired in 1983.

***

Kathleen French is holding her phone, switching Pandora stations to something she wants to listen to at the gym. The ringer is off, so there is no alert sound: A white box suddenly overrides Pandora, takes over the screen.

I'm going to die. Kathleen believes this, immediately and viscerally. Or she will survive and suffer horribly. She does not, in that moment, weigh the relative merits of either outcome.

***

"I need you to bring Lucas here," Daphne says. "I want you with me."

Wade understands that as a practical matter of survival, this makes no sense, driving from Diamond Head to downtown, closer to Pearl Harbor, which probably is the intended target if, in fact, anything at all has been targeted. But maybe it'd be better. Wade's not afraid of dying, only of doing so slowly and horrifically. And if they're all going to die, shouldn't they do it together? Death, a good death, always seems to involve loved ones gathered around, doesn't it? "Deathbed" is supposed to be a comforting word... It's about a 12-minute drive from Wade's condo to Daphne's. It's Saturday morning, so traffic probably won't be too bad. Still, Wade thinks, dying on Interstate H-1 would be a pitiful way to go. The only thing worse would be yelling at his son when the sky flashed.

These are, no doubt, lovely people who, no doubt, dearly love their families and only wanted to do what was best in an unexpected crisis situation for which, no doubt, they were completely untrained. They are, no doubt, blameless.

Nevertheless, this was the stupidest thing I've read in a month -- and, folks, I'm on Twitter. In a real nuclear attack, every one of these people could have virtually guaranteed their own survival by simply not doing anything stupid. But, instead, they all decided that they were doomed, that everything was pointless, and so they all immediately did a lot of stupid things that very well could have gotten them killed or severely injured. Say what you will about #WhoFundsTheFederalist; the thousands of participants may have the collective IQ of a lobotomized ferret, but they're probably not going to get anyone killed. This kind of nuclear nihilism, sooner or later, certainly will.

Let's start with a word about the Cold War. Well, two words about the Cold War:

It's over.

There was a time when "nuclear war" really did probably mean the end of human civilization. This was before I was born, but my parents were born into it and lived it for the majority of their lives. In those days, the United States had tens of thousands of high-yield, multi-megaton H-bomb warheads mounted on intercontinental ballistic missiles and carried by nuclear submarines, all pointed at the Soviet Union... and the Soviet Union had a comparable arsenal pointed back at us. The defense doctrine of both nations was "if they nuke us, or nuke any of our allies, then we will retaliate by launching our entire arsenal." I don't think anyone really knows how many megatons it would take to send Earth's biosphere into an irreversible death spiral, with survivors of the initial blasts dying off from starvation, nuclear winter, and ubiquitous radiation poisoning... but there seems to be general agreement that the number is well below 20,000 megatons.

But that is not the world we live in anymore. There's a reason all the Fallout games set the nuclear apocalypse in the '50s: a civilization-ending nuclear war wouldn't be plausible in the '90s, nor is it plausible today.

We have entered the age of regional nuclear powers. You don't have to be a world-striding superpower to have the Bomb anymore. You can be Pakistan, which has few foreign policy ambitions other than keeping India at bay (and vice versa). You can be China, which really is on the cusp of superpowerdom, but is content for now to assert its authority over Southeast Asia and the eastern Pacific. You can be Israel or (in the next few years, probably) Iran, both of whom want nuclear weapons mostly because they're afraid of their neighbors. Or you can be North Korea, a nation whose whole strategy for holding a hostile world at bay is "mutually assured mass casualties."

Nobody has 20,000 megatons of nuclear firepower pointed at each other anymore; in fact, there aren't that many warheads left on the whole planet. Over 90% of the world's nuclear arsenal, moreover, and far more than 90% of the world's actual nuclear destructive potential, remains in the hands of the Cold War superpowers: Russia and the United States. The nuclear powers we are most worried about today have relatively small stockpiles of nuclear weapons with relatively low yields. Many of them could not even hit the U.S. with any of their nukes; they don't have nuclear bombers, nuclear submarines, or nuclear missiles with sufficient range. Destroy the world? They can't even hit the western half of it. Even if they could, it would only be with a small number of weapons, many of which (we hope) would be intercepted by the U.S.'s missile defense system. Even if they got past missile defense, the nukes would be pretty low yield.

"But, James, why bother fiddling with details like yield? A nuke is a nuke! It'll wipe my city off the map, and you're just wondering how tall the mushroom cloud will be!"

Well, no.

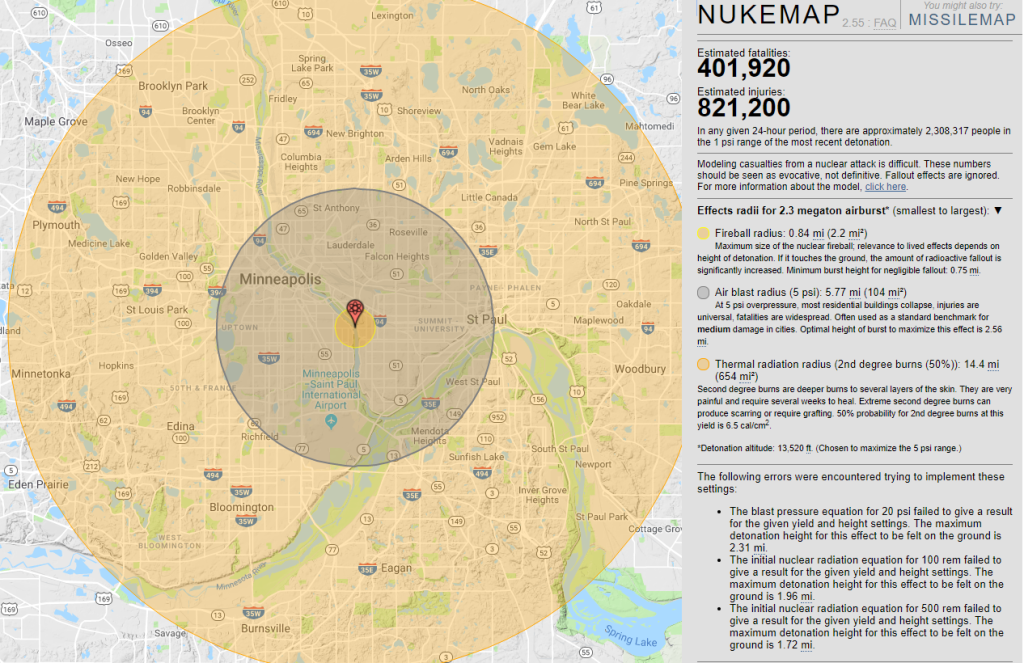

Here's a simulated nuclear detonation that actually would wipe out a city. In fact, it'd wipe out two cities! Let's say Russia drops a 2.3 megaton bomb on the Marshall Avenue bridge that joins the Twin Cities of Minnesota, St. Paul and Minneapolis. Why the Twin Cities? For one, it's an extremely average American metropolitan areas, right in the middle of most size and wealth indexes. For two, it's where I live. Boom:

The bright yellow spot is the fireball. I work a few blocks from there, so I die instantly. :(

The gray circle represents the main force of the shockwave; most buildings within it will be knocked over, and you'll notice from the map that this shockwave hits both downtowns.

The orange circle represents the flash burn radius: if you're outside or near a window when the bomb hits, everyone within this circle stands a pretty good chance of getting second- or third-degree burns. In fact, everyone from Shoreview to Eagan who can see the detonation is pretty much definitely going to get extensive third-degree burns. You'll notice that's most of the circle. Also, if you're outside the shockwave but inside the burn radius, there's a non-zero chance the flash burns will start your house on fire, especially if you haven't painted lately.

As you can see, the Nukemap estimator places the casualties at roughly 1.2 million... and that's before we start dealing with the fallout. This is the scenario you Cold Warriors grew up imagining. The Cuban Missile Crisis was over a batch of 2.3 megaton warheads. The bombs in The Day After seem to have been on about this scale. This scenario is catastrophic. A 2.3 megaton nuclear bomb dropped on the Twin Cities would effectively destroy the metropolitan area. Survivors would be reduced to refugees.

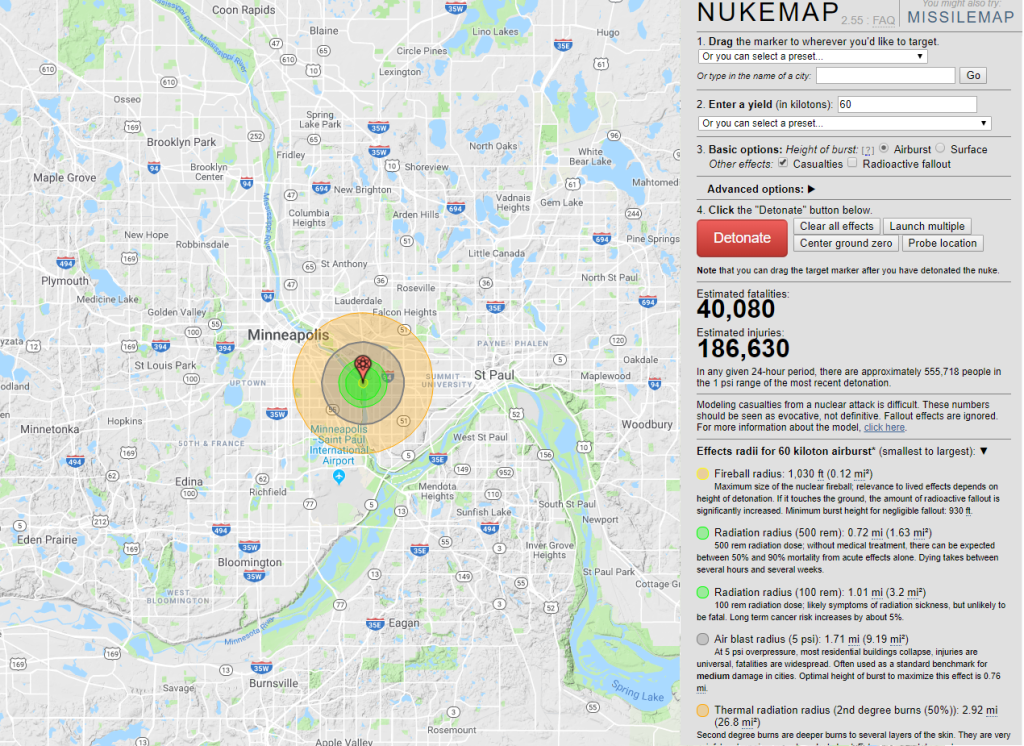

But the next bomb to drop probably isn't going to be a multi-megaton bomb. It's going to be a smaller bomb launched by one of these smaller regional powers. Here's a simulated nuclear attack on the same target, the Marshall Avenue bridge... but, this time, the attack is made by Pakistan.

Most of Pakistan's nukes are in the low kiloton range, not much larger than the Hiroshima bomb (which was 15 kt). Pakistan's largest-ever test was of a 40 kiloton (0.04 megaton) bomb, although analysts suspect they have at least a few bombs in the 100-500 kiloton (0.1 - 0.5 megatons) range. (Also, none of their weapons have range to hit the U.S., but we'll hand wave that for the sake of the exercise.) This simulated bombing assumes a 60 kiloton detonation:

Wow, what a difference a few thousand kilotons makes, right?

In this bombing, you can barely see the fireball radius (feel free to click through and take a closer look). It destroys the bridge itself and the nearby country club, but not much else. I still work a few blocks away, but I survive the fireball!

The green circle represents the radius of serious, acute radiation poisoning. (That is, instantaneous radiation from the detonation itself, not from the fallout.) At 500 rems, I need medical treatment, or I will die in hours to weeks.

But, hey, look at that -- we've got quite a few decent hospitals in the area, and only one of them gets knocked over in this bombing (Shriner's Hospital for Children). The downtown areas will have a lot of broken windows, but we aren't going to see any skyscrapers toppling, the suburbs are basically fine, and most residents of the Twin Cities aren't even in the flash burn radius.

40,000 dead, nearly a quarter million casualties, widespread power outages, but our cities will continue functioning. For most of us -- well, most of you, anyway, I'm in the green circle so it's pretty iffy -- life will go on. After 9/11, Wall Street was literally covered in debris from the WTC collapse, but still re-opened in less than a week. We would bounce back, too, and -- sooner than you think -- the political parties would be blaming each other for the attack and Oliver Stone would be making a movie about it and you'd stop asking everyone you met where they were the day the bomb fell.

That is, assuming you weren't some blame fool who got in a car with your kid ten minutes before the bomb hit in an suicidal attempt to be reunited with your spouse before you're killed. If you do that, you will definitely die, and everyone will feel embarrassed for you. Your kid will also die, and it will be your fault. Do not do this. In fact, do not do anything the people from the GQ article did in the excerpts I quoted.

Do this instead:

1. Get to shelter! Your best shelter is the same place you shelter in tornado drills or earthquake drills. Usually, this is the basement at your home or workplace. For those without basements, you undoubtedly have arranged a storm shelter of some kind. Use it!

P.S. Make sure your home shelter has basic disaster supplies: at least three gallons of water per person and three days' non-perishable food, flashlight, batteries, a radio, a whistle, and other basics. You should already have this stuff in case of natural disaster, and a nuclear disaster is no different. Try and put the electronics in a sealed metal bucket (here's a good one) lined with non-conductive material (like cardboard); the nuclear attack may include an EMP element, which might destroy unshielded electronic equipment.

2. Duck and Cover! You've got a nuclear fireball, a hefty dose of radiation, and a concussive shockwave that will knock down buildings and shatter windows, all coming straight for you. Just like tornado drills: duck and cover. We all know Bert the Turtle is funny, but listen to him! He might save your life.

3. Clean up! Contrary to popular belief, most radiation poisoning in a nuclear attack doesn't come during the initial blast. Most of it comes a few minutes later, when dirt and particles blown up into the sky by the blast comes back down (often as a form of dirty and highly radioactive rain), which may begin 10-15 minutes after the bomb. If you were outside, or had any contact whatsoever with the outside world after the initial blast, you need to make sure you didn't bring any fallout into the shelter with you. It can poison you and your family just as easily. (Assume everything that was outside, or which has been exposed to the outside, since the blast is covered in fallout and can kill you.)

Remove and replace your clothing (get your original clothing outside your shelter), then wash your entire body with soap, water, and shampoo to ensure you got it off of you. If you can shower safely, do so. Were you inside when the bomb hit? Good! You may be fine. But your basement windows will have shattered in the blast. If your shelter is in a room with no windows, perfect; stay there. But if you have open windows, seal them now (with plastic sheeting and duct tape from your emergency supply kit), then assume you've got fallout on you from the broken window and clean up accordingly.

4. Stay inside! Stay tuned! Listen to your radio (from your emergency supply kit) for updates and instructions from local emergency authorities. You should remain inside for at least 24 hours to allow fallout to settle and dissipate outdoors. And your supplies should last three days, so why not go for it? That said...

5. Evacuate if necessary! A nuclear attack will cause scattered fires throughout a wide area thanks to the flash burns. Emergency services are likely to be overwhelmed in the immediate aftermath of an attack, and may not be able to put out fires. These scattered fires, combined with the much more intense fires near the center of the city, can lead to a terrifying situation called a firestorm, where a major fire combines with hurricane-force winds to burn a huge area. This is what happened in the Dresden firebombing in World War II.

A firestorm doesn't happen after every nuclear attack. Hiroshima had a firestorm; Nagasaki did not. Hopefully the houses in your neighborhood, not being made of paper, will stand up to the challenge fairly well. But, if a firestorm does develop, it is extremely dangerous. Radiation might kill you in a day or a decade, depending, but fire will kill you in about a minute flat. If you have no choice but to evacuate or burn, evacuate, and worry about the radiation poisoning when you're safe. Before evacuating, listen for updates on your emergency radio; emergency officials will hopefully be tracking the situation and will hopefully be broadcasting the safest escape route.

***

For more, visit Ready.gov. They've been working on this for 75 years. Even though we don't have civil defense training anymore (and we should think about restarting it, given recent world events), the government hasn't forgotten what they learned in the Cold War. They have some pretty decent advice... and it's not just theatrics to keep a doomed population from panicking. You can survive a moderate nuclear attack. It will be a catastrophe, but one we can rebuild from.

And if you don't take these sensible steps to make sure that you're alive for the rebuilding, I'm going to come out of my radiation cloud as a Super Mutant, I'm going to find you, and I'm going to kick your fatalist butt.