My Chat with Judge Hardiman (Or: Harriet Miers and the Hasty Tweet)

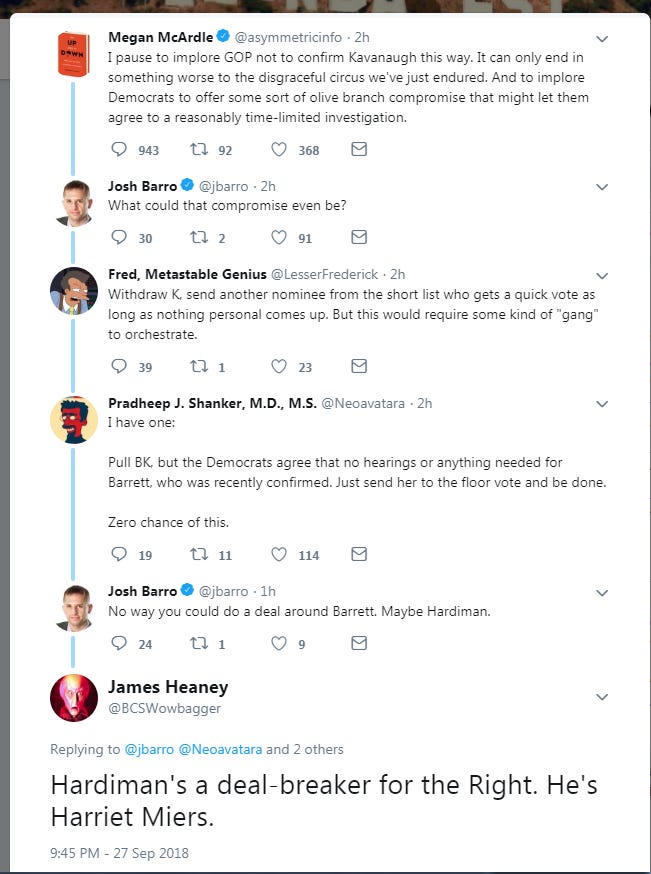

Last night, about an hour before Judge Thomas Hardiman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit phoned me, I jumped into a Twitter thread:

Not all of my readers were tuned into judicial politics back in the days of Miguel Estrada and the Gang of 14, so let me explain that tweet a bit before I get to the exciting stuff.

Harriet Miers was George W. Bush's original nominee to fill the seat of retiring Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O'Connor. Miers was the White House counsel and a close adviser to the President... a President who had recently won an election thanks to Catholic and evangelical "values voters." Calling her "a pit bull in size 6 shoes," President Bush vouched for her integrity, her legal chops, and her work ethic.

The problem was, Miers had a very thin record. She'd worked as a commercial litigator before becoming the personal lawyer of then-Governor Bush. She was an able lawyer for her clients, but there was no public record showing what she herself thought about the Constitution, the judicial branch, or the pressing issues of the day. President Bush believed that his personal assurances would suffice.

They did not. Republicans had been burned several times before. Sandra Day O'Connor, Anthony Kennedy, and David Souter had all been nominated by Republican presidents who gave assurances that the nominees would turn out to be excellent, judicially conservative judges.* Once on the Supreme Court, all three showed their true colors... and those colors did not have much to do with the Constitution.

All three supported (and, in fact, crafted) the plurality in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which Michael Stokes Paulsen rightly called "the worst constitutional decision of all time." Kennedy is famous for declaring same-sex marriage a constitutional right in Obergefell, a decision which, even if you agree with its conclusion, is totally incoherent both internally and in light of Kennedy's own precedents (especially Casey!). O'Connor struck down a modest law against partial-birth abortion in 2000's Stenberg v. Carhart and personally saved affirmative action from history's dustbin in the bizarre Bollinger decision. And Souter simply joined the Court's left wing outright, voting reliably with Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, and Stephens for most of his tenure.

So President Bush's personal assurances did not reassure the thrice-burned right wing, especially the pro-lifers, however well-liked he was. Activists had trusted the words of Edwin Meese, John Sununu, and George H.W. Bush decades earlier, let nominees slip by with little paper trail, and so lost their chance at the Court for a generation. There was simply nothing out there to demonstrate Harriet Miers' bona fides as a textualist who followed the Constitution. There was no way of knowing whether she would be another Scalia... or another Souter.

Conservative martyr Robert Bork called Miers' nomination a "slap in the face" to the conservative legal movement. Unable to sell the nomination to the very demographic who had just re-elected him, Bush was forced to "allow" Miers to withdraw a few weeks after nominating her. The seat went to Samuel Alito instead.

Which brings us to Thomas Hardiman. Judge Hardiman sits today on the Third Circuit. He has shown up on President Trump's Supreme Court shortlist twice in a row, losing out to Judge Gorsuch in 2017 and Judge Kavanaugh in 2018. He has faced some important issues in his time in the judiciary, and he has often acquitted himself as a textualist. His work on the Second Amendment is particularly well-regarded among conservatives. It is believed that he appeals to President Trump in part because of his phenomenal biography: Hardiman is one of too few federal judges who come from outside the Ivy League, with an undergraduate degree from Notre Dame and a J.D. from Georgetown, which he paid for by working nights as a taxi driver.

However, I have concerns about Judge Hardiman, as do some others. As with Ms. Miers, though I bear Judge Hardiman no ill will, I am not confident that Justice Hardiman would adhere to the Constitution on the issues that matter most. (P.S. As with everything in our utterly dishonest judicial politics, that's code for "Roe v. Wade.")

And, as you can see, I said as much on Twitter! So far, so regular Thursday. But my night was about to take a surprising turn.

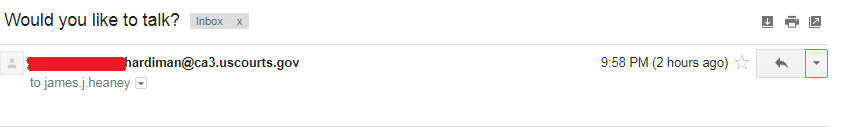

A few minutes after my tweet, I got an email with no body but a heck of a FROM line:

(I've obscured the full email address because, while I'm sure it isn't a state secret, Judge Hardiman's professional email address is also not, as far as I know, public knowledge.)

I wrote back with my phone number, and, 90 seconds later, I got a call from the 412 area code. The man on the other end introduced himself as Thomas Hardiman, and said he wanted to touch base with me.

I am not a smart blogger, so I did not record the call. I did start writing this blog right away, so the call would be fresh in my memory, but this is still reconstructed from my scant notes, not verbatim. Please bear that in mind. Throughout our conversation, Hardiman was friendly, gracious, and respectful. If he was at all frustrated with me or what's said about him, it didn't come through in his tone or his words. While my account may read like Hardiman talking a lot and me listening, we had a good give-and-take. (It's just that what I said isn't really newsworthy, so I've omitted much of it.)

Judge Hardiman said he had seen my tweet and wanted to register his polite disagreement with my assessment of him. The idea that he is some kind of a David Souter, Hardiman said, has been in circulation in certain parts of the Right, and he doesn't think it accurately reflects his record. In particular, Hardiman said that the Wall Street Journal had said some things that were not altogether fair to him... particularly once the Journal became enthusiastic about Judge Kavanaugh.

And, fair enough. Once it picks a side, the Journal certainly has been known to throw spitballs. I remembered a piece the Journal ran in July which was, indeed, quite critical of Judge Hardiman:

The biggest gamble would be if Mr. Trump went beyond those three to choose Thomas Hardiman of the Third Circuit Court of Appeals. Mr. Hardiman is said to be easier to confirm because he had a hardscrabble upbringing. But that's the Souter trap of putting biography over a legal record. Our reading of Judge Hardiman's opinions is that they are not as impressive or extensive as those of either Judges Kavanaugh or Kethledge.

I suspect that wasn't their only piece promoting Kavanaugh or Gorsuch at Hardiman's expense.

I chimed in, though, that there's a lot of suspicion of Hardiman on the Right because he is strongly supported by Judge Maryanne Trump Barry. Judge Barry serves with Hardiman on the Third Circuit and (according to reports) personally pushed Hardiman's name forward when President Trump was considering Justice Scalia's replacement. This may have carried a lot of weight, because Judge Barry is President Trump's older sister. Unfortunately, while a George W. Bush appointee, Judge Barry is widely reviled on the Right (or, at least, in my corner of it) because of an aggressively pro-abortion rights opinion she wrote in 2000, which not only struck down a New Jersey law against partial-birth abortion, but went beyond what the Supreme Court required in Stenberg v. Carhart and dripped, frankly, with contempt for the pro-life cause.

Now, I did hasten to add that, as Ed Whelan pointed out in 2017, Judge Barry's very bad decision in Planned Parenthood v. Farmer and the very poor comportment of her little brother does not mean everyone Barry likes is terrible forever. After all, Barry was a big fan of Samuel Alito (her colleague who dissented in that case), and he's turned out wonderfully. But, still... if she thinks Hardiman's the right guy for the Supreme Court, with her very problematic views on at least abortion law, how much can those of us with different views feel confident that Hardiman's our man?

Judge Hardiman answered that his relationship with Judge Barry, as well as the other judges on the Third Circuit, is a sign of his ability to build strong relationships with others, regardless of party or nationality or religion, and to win their respect despite frequent disagreements. Judge Barry respects him, and he likewise, but this doesn't mean they're of the same judicial mindset.

Hardiman called my particular attention to the case Busch v. Marple Newtown School District. Hardiman called his opinion in this case -- gosh, I wish I'd written this down -- but it was something like, "A dissent that really goes to the heart of who I am as a judge."

In Busch, the parents of a kindergarten boy, one Wesley Busch, had been invited to Wesley's class to participate in "All About Me" week. Each student's parents were invited to a kind of parental "show and tell" where they would share "individual interests," perhaps taking the form of a "small craft or story." Young Wesley asked his mom to read a short passage from his favorite book, the Bible. The school principal barred this, saying that it would violate the "separation of church and state." The parents disagreed, arguing that this violated their First Amendment rights. The school won the case, with Judge Barry joining the decision in separate concurrence.

Judge Hardiman, however, dissented. In his conversation with me, he described the school's (and the court's) position as "straightforward viewpoint discrimination," which is simply inimical to the First Amendment. It's a dissent he is proud of, and nicely illustrates his view of the Constitution. I had to admit I had not read the case in my previous review of his work.

Judge Hardiman also commended to me his decision in Pennsylvania v. Trump, where he ordered that the Little Sisters of the Poor be permitted to join an ongoing lawsuit over Affordable Care Act regulations in order to protect their hard-won right to conscientious objection from the ACA's contraception mandate. I told him I had read this opinion and liked it, but, now that I'm looking at it, I'm realizing I have never read this; I had this confused with one of the other contraceptive mandate cases. Shoot.

Above all, Judge Hardiman wanted to emphasize to me that he takes the Constitution very seriously. The Constitution, its structure, the republic it gave us: these things, Hardiman said, are what attracted him to the practice of law and the judiciary in the first place. He mentioned that he wants all the best for Ray Kethledge and Amy Coney Barrett, both of whom he counts as friends and both of whom would make, in his view, excellent Supreme Court justices, but contended his own view of the Constitution comes through clearly in his written opinions.

Here I interjected. When I compared him to Harriet Miers, I wasn't trying to say there that Judge Hardiman would necessarily be a bad Supreme Court justice. He might very well be a great one. There are certainly reasons to think so. Harriet Miers might well have been a great justice, too. There were reasons to think that, too.

The trouble, for me, is that I don't see in Judge Hardiman's public record adequate assurances that he thinks the way I do about the constitutional issues that matter most to me.** He may very well think as I do, but I haven't been able to prove it to my own satisfaction. Although, I had to admit, I am not nearly as familiar with Hardiman's body of work as he is, I couldn't look in his history and find a really reassuring case like Garza v. Hargan, the case where Judge Kavanaugh argued convincingly against a government duty to facilitate an abortion for an unaccompanied minor who illegally entered the country. Kavanaugh did his duty as a lower-court judge, obeyed the Casey precedent, and did not expand his argument beyond what was necessary, but his interpretation of Casey was narrow and relied on language that pro-lifers found as encouraging as pro-choicers found it alarming.

Of course, not every issue comes before every court. Hardiman has no record on abortion, he noted, because he has faced no cases that are directly about abortion. I said, "Well, Judge, what I really want to ask you is: if named to the Supreme Court, would you be a reliable vote against Roe versus Wade? But, of course, I can't ask you that question, and you can't answer it, and, if you did answer it, you would never be confirmed to the Supreme Court." Chuckling, Judge Hardiman agreed: I could definitely not ask him that question.

But, while he hadn't ruled on abortion directly, he did point out the closest thing he'd had to an abortion case, United States v. Marcarvage, where Hardiman joined an opinion protecting an anti-abortion protester who had been convicted of violating a protest permit by protesting outside a designated area. He also mentioned other areas where "the Left" had pressed hard on the Constitution, but where he had stayed true to it, which he thought was enlightening about his overall approach to law. He pointed me in the direction of his Second Amendment jurisprudence, which has indeed earned him a sterling reputation among judicial conservatives. In that jurisprudence, particularly his dissent in Drake v. Filko, Hardiman has been one of relatively few lower-court judges who have been willing to read Heller and McDonald in (what I consider) an honest fashion, contending that the individual right to bear arms recognized in Heller was improperly subjected to a "justifiable need" test by the state of New Jersey.

Hardiman also said that, for a fair overview of his work as a judge, not written by a conservative but by someone who was very fair-minded in assessing him, I should look up Amy Howe's 2017 profile of Hardiman for SCOTUSBlog. Now, of course, I read all the SCOTUSBlog profiles voraciously whenever a vacancy opens up, because SCOTUSBlog is great... but I will definitely be rereading this one now that I know it isn't just Amy Howe's take on Hardiman. It is, in Hardiman's own opinion, one of the best public overviews of his judicial thought out there.

Overall, Hardiman considered my comparison to Miers somewhat unfair, or at least inaccurate, for this reason: Harriet Miers had been a corporate lawyer, and never really had the opportunity to express her judicial philosophy during her career. As I characterized it, we were asked to take her on faith. But Hardiman is a federal judge. He's been there for a while. Between majorities, concurrences, and dissents, he has over a hundred written opinions to his name, to say nothing of all the opinions he's joined over the years. "Once you have that many opinions, you can't hide what kind of a judge you are."

At this point, I offered to take down the tweet that had started all this. Twitter not being a good place for nuance, I had dashed off the tweet rashly, without expecting that anyone on Earth would read it, much less that Judge Hardiman himself would bump into it. I mean, he has a point! Whatever my reservations about Hardiman, he does have a paper trail, and, by historical standards, it's fairly thick. Comparing him to Harriet Miers was glib. It got my point across, but, like so many glib tweets, it also wasn't fair. Talking to the man himself made me realize that. It's not the first time I've been too quick off the block with a hot take on Twitter.

However, Judge Hardiman insisted that I feel under no obligation to take down the tweet. "You have every right to your opinion," he said. "I'm a big believer in the First Amendment." Even when people express very bad ideas, Hardiman believes they generally have a right to say them. Hardiman called to have a chat with me about how he sees his own record, not to argue with me for tweeting a criticism of him. (I still plan to delete the tweet.)

I eventually wondered, "Why me?" I'm surely not the only person on Twitter who's talked about Judge Hardiman in the past few days, especially with how rocky the Kavanaugh hearings have gone. Hardiman said that he reached out to me because he had taken a look at my blog after seeing my tweet and thought it showed I was a "deep, intelligent" guy with some interesting ideas. There are a lot of fever-swampy areas on the right-wing blogosphere (he didn't use that specific term), where reaching out would not be productive, but Hardiman expressed that he thought he could have a conversation with me, given what I'd posted on the blog. Of course, some might argue that liking my blog is a sign of bad judgment! But I, for one, am flattered.

Soon thereafter, we thanked one another for our respective time, I wished him well in his career prospects, and we hung up the phone. All told, I figure we talked for about 15 minutes. Feel free to critique my interview technique. There are many questions I should have asked but was too discombobulated to work out. But that's on me.

I spent the rest of the night kicking myself for failing to ask Judge Hardiman about his feelings on Justice Anthony Kennedy. Longtime readers of this blog will know that I think Kennedy is the worst Supreme Court justice, worse even than more consistent ideological opponents of mine like Ginsburg and Kagan. (Jeffrey Rosen is no ally of mine, but his take on Kennedy for The New Republic is more or less right.) But Judge Hardiman, like Judge Kavanaugh, clerked for Kennedy, and I understand there's considerable personal and professional affection between them. I'd love to have gotten some insight into that relationship, and particularly how Judge Hardiman would compare and contrast himself with Justice Kennedy. But I didn't! Sorry, readers.

So what are my takeaways?

In one sense, nothing has changed. Hardiman didn't reveal anything shocking to me. His record is still exactly what it was before our conversation, and that record is still missing enough to make me uneasy. You can call me a paranoiac if you like, and you'd probably be right, but the specter of O'Connor and Souter and Kennedy haunts my dreams. It takes a very high standard to put me at ease about a judicial nominee, and, until I actually sat down and read Garza v. Hargan and a few other cases, I was pretty worried about even Judge Kavanaugh's conservative thinking.

With Kavanaugh, though, I could always look for reassurance to his strong score on the Clerk-Based Martin-Quinn scale, a test that infers a judge's ideology based on the ideology of Supreme Court justices for whom the clerk has worked. Hardiman has no CBMQ score, because his clerks have not gone on to the Supreme Court, so we're left with his Judicial Common Space score. Hardiman's JCS score is crap, placing him firmly in the Kennedy centrist region... but the JCS is kind of a crap measurement to begin with. (It measures the ideology of the people who appoint judges rather than anything done by the judges themselves.) So I'm not going to hold Hardiman accountable for the people who appointed him. But it does deprive me of a source of reassurance.

If I wanted reassurance with Gorsuch, I could just go read his book or his marvelous paeans to Justice Scalia. With Barrett, I could just go rewatch Senator Feinstein's bigoted "dogma lives loudly" attack on her, or look at her very thoughtful writing on the dangers of overreliance on stare decisis**. With Hardiman, I never knew where to go to find clear declarations of his judicial philosophy.

But that, at least, has changed somewhat. Hardiman has personally pointed out to me the opinions he thinks are most useful to commentators trying to suss out how he views the Constitution: Busch v. Marple Newtown, the Little Sisters of the Poor intervention in Pennsylvania v. Trump, and his Second Amendment jurisprudence. I can now read (or re-read) those opinions, knowing that they are central to Hardiman's thought, and judge him again in their light. Whether I'll be impressed or left sharing the Wall Street Journal's impression, I don't know, but I'll give his thinking a fair second look before I draw new conclusions. I owe him that much, after his respectful call.

Speaking of which, another thing that's changed: it's hard not to be charmed by someone who calls you out of the blue to politely debate your thoughtless tweet. And Judge Hardiman was charming and honest throughout. Before tonight, I neither liked nor disliked him. He was a guy from the news whose writing I needed to judge. Now, I like him. He seems like a nice guy, and he apparently shares my weakness for late-night Twitter -- but at least has the fortitude to not actually tweet. (Never tweet, kids.) If he's ever in the Twin Cities area, I'd love to grab a drink with Judge Hardiman.

Moreover, I think it's revealing that Judge Hardiman is sensitive to my comparison of him to Harriet Miers or the even less kind comparison to David Souter that's out there. (He did actually use the word "sensitive.") If he does see himself as a more moderate or left-leaning judge, it would a bit strange of him to call up (let's be honest here) an obscure blogger who characterized him that way to dispute the point. He is determined to be seen as a judge who is faithful to the text of the Constitution, even by folks like me who don't really wield any influence. He stands to gain very little from convincing me he really is a judge who adheres closely to the Constitution, which suggests that the reason he was trying to convince me adheres closely to the Constitution is that he actually does adhere closely to the Constitution as a matter of conviction.

I'll note that it is intriguing that we had this conversation last night, a few hours after the Kavanaugh-Ford hearings, and leave it at that. I'm not sure what, if anything, to read into that, so I won't.

I think we learned tonight that Judge Hardiman follows @asymmetricinfo; otherwise, I can't imagine he would have seen my tweet at all. That is an excellent choice that speaks well of him personally and professionally.

Which leads me to my last takeaway from tonight: be kind on Twitter. You never know who might be reading.

*In the parlance of the times, they were called "strict constructionists." Strict constructionism has been rightly critiqued and the conservative mainstream evolved into textualism.

**This is, again, always, code for Roe v. Wade.