My Chat with Commissioner Simington (Or: Fifteen Questions I Asked a Republican FCC Commissioner)

Readers, I owe you an apology. Three weeks ago, when I posted Fifteen Questions I Would Like To Ask a Republican FCC Commissioner, I very strongly implied that it was a hypothetical exercise.

It was not.

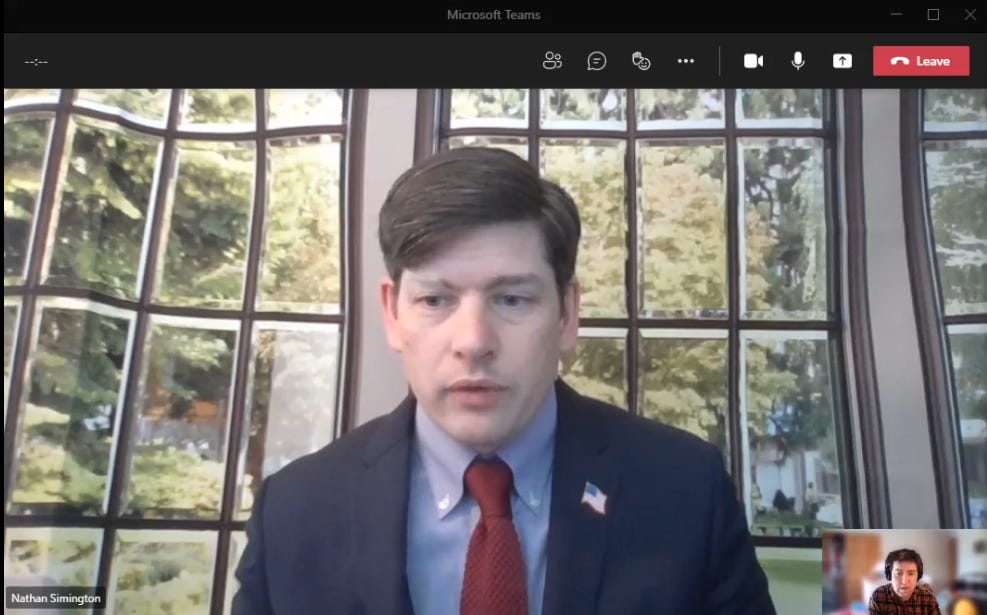

Early in May, I received an email from Republican FCC Commissioner Nathan Simington. Simington said that he'd read my 2014 Net Neutrality article, "Why Free Marketeers Want To Regulate the Internet" a few years ago. Now that he is on the FCC, he is trying to figure out how to approach Net Neutrality, so he was looking for informed perspectives outside the bubble of DC policy discourse. Would I like to sit down with him on a video call and talk about it for a little while? I wrote my Fifteen Questions as preparation for our discussion.

We talked on my birthday, and, because I am the biggest nerd of all, it was the highlight of my day.

To be fair, I didn't just enjoy geeking out about telecom. Commissioner Simington was genuinely a lot of fun to talk to. Here are three things that made me very fond of Nathan, despite our policy disagreements:

He has excellent taste, by which I mean he praised my writing. Now, as a Minnesotan, I naturally accept all criticism as incontrovertible, and I naturally dismiss all praise as flattery. Yet Simington has no reason to flatter me, a rando blogger with 12 regular readers, so maybe my writing is indeed not too bad.

He did the homework. Obviously, one would hope that an FCC commissioner would be familiar with, at the very least, the contents of major FCC orders, but I have been known to harbor doubts. Commissioner Simington knew the FCC material to the paragraph. Beyond that, he opened our conversation with a short sidebar about international telecom regulation (which I know next to nothing about), he casually recommended an out-of-print book about the AT&T breakup—a topic I'm very interested in but understand far too little about (I'm reading it now and loving it)—and he extensively quoted my own writing back at me. He even referred to the thesis of a long, obscure article (by someone who is downright radioactive in Washington circles) that I had linked to in an aside. So Simington didn't just read my articles; he read the links! It is always a pleasure to have a conversation with someone who knows what he's talking about, knows whom he's talking to, and who earnestly desires to know even more.

He's a nerd. We nerds recognize fellow nerds in the wild—it's an essential high school survival skill—and I got the nerd vibe almost immediately. Based on his biography (and perhaps my own prejudices about the Beltway), I did not expect this. But after Simington mentioned writing code in the early aughts, I casually mentioned Eternal September. Not only did he know what I was talking about, he was there! Nerd confirmed! If he'd been born ten years later and a thousand miles southeast, I've little doubt I would have met him at an Orange Box LAN party in high school and ended up buds.

So, all telecommunications policy aside, I feel I made a new friend this month. Should the good Commissioner ever find himself in the Twin Cities—with or without family in tow—he's got himself a standing invitation to dinner at my place. (I'll make my world-famous pasta carbonara.)

Yes, I am aware that many politicians have a kind of charisma superpower that makes you love them, often despite your best judgment. I've experienced it occasionally. (Cardinal Christoph Schönborn has a charisma I can only describe as "overpowering.") I detected no sign of it here. All I saw was hard work and gracious intelligence, and it's not like FCC commissioners have to kiss a lot of babies to get elected. But if you want to take the rest of this article with a grain of salt because I'm clearly fond of Commissioner Simington, hey, that's exactly why I'm trying to be transparent here. (I respect Judge Hardiman, but I felt no need to put anything like this before my article about him!)

Alright, so what'd we actually talk about? It took me a few days to figure out how to write this article. Our discussion bounced all over the place, and, looking back at my notes, it was absolutely riddled with jargon that I'm going to have to either avoid or explain, from "nodes vs. servers" to "pizzeria argument." (You will have a much easier time with this article if you read my previous article, "Fifteen Questions I'd Like to Ask a Republican FCC Commissioner," first.) Let's start out easy, by talking about Simington himself.

The Dark Horse Commissioner

Nathan Simington entered law relatively late in life, around the time of the financial crisis. He was in the legal industry for a few years. He was Senior Counsel at Brightstar (a wireless services company) when he was chosen to serve as a senior advisor to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, an agency which... I'll just let Simington explain:

NTIA is within the executive branch, and what it is, it's basically the federal spectrum counterpart to the FCC. It has other stuff it does as well, but the idea is that it wouldn't make sense to have the FCC regulate all spectrum. There's a power-sharing memorandum of understanding between the two agencies. So if DOD needs to do something or FAA needs to do something, it's not usually subject to the Communications Act. And in fact, there's a carve out to allow NTIA to regulate them instead. So it's sort of a balance of power thing, which—and again, like a lot of things in the U.S. government, it's ultimately about allocating power between the executive and legislative branches.

(The NTIA does lots of other stuff, as he said, but this was the work that sent him in the FCC's direction.)

Simington was only at NTIA for about six months. He spent it in the political front office working with the acting administrator. The administrator was very busy addressing the Trump Administration's executive order on Section 230. Sure, it's on the scrap heap of history now, but it occupied a lot of NTIA time in 2020! A big part of Simington's job was to run interference for the administrator on, well, just about everything else. At one point, he got involved in a spectrum allocation controversy; a satellite company wanted to modify its licenses in order to offer 5g IOT services for surface transportation, and the Department of Defense freaked out, saying it would destroy GPS. This got him into spectrum regulation, where, he avers, he is still most comfortable.

In August 2020, President Trump withdrew FCC Commissioner Michael O'Rielly's re-nomination after O'Rielly expressed "deep reservations" about the Section 230 order. Nathan Simington was the surprising replacement nominee. Some on Capitol Hill questioned Simington's qualifications, because he wasn't a a telecom lobbyist, an FCC insider, or an ex-Senate staffer (the traditional roads to an FCC commissionership). Me, I'm suspicious enough of technocratic group-think that I like nominees who break the mold a little bit, although Simington himself notes that his qualifications are not historically unusual, and it's not like telecom was terra incognita after his work at Brightstar. Breitbart was thrilled with his nomination.

Still, there were real reasons to doubt he'd be confirmed. Democrats interpreted Simington's openness to reconsidering Section 230 to be a sign of partisan fealty to President Trump, and opposed him accordingly. Less Breitbart-y Republicans, for their part, seemed reluctant to confirm a nominee who wasn't a well-known part of the telecom lobbyist establishment... particularly someone who did not come pre-programmed with all the uncomplicated, "correct" partisan answers to all regulatory questions. In Simington's telling, there were some Republicans who "clearly regrett[ed] that, by that point, I was the only nominee confirmable prior to the change of administration."

But, after Biden narrowly won the election, Simington was the only nominee confirmable prior to the change of administration. Republicans (who still expected to retain control of the Senate, and thus the ability to block or delay Biden nominees) had exactly one chance to deadlock the Biden FCC with 2 Republicans and 2 Democrats. Thus, on December 8th, Simington was indeed confirmed, on a party-line 49-46 vote.

Since Republicans did lose control of the Senate, the FCC deadlock will not last forever. President Biden's choice for the final seat on the FCC (the chairman) will be confirmed by the Senate, likely at some point in 2021. In my opinion, once the FCC has a 3-2 Democratic majority, net neutrality regulation (via Title II of the Communications Act) will become more or less inevitable.

But isn't that pretty normal? Is that not, in fact, kind of clearly Congress's intent in the Telecommunications Act of 1996? My first five questions for Commissioner Simington all revolved around the text and history of net neutrality regulation. It is my opinion that Republican commissioners have repeatedly cast aside both in their attempts to "return" the Internet to an unregulated past—a past that is almost entirely imaginary.

My First Questions: Text and History

When I claimed that net neutrality regulation has been the norm over the 32-year history of the public Internet, Simington agreed... to a point. He agreed that "some sort of net neutrality regime has been pretty common," noting that none other than Bush chairman Michael Powell called for net neutrality in his "Four Freedoms" speech just a year after Tim Wu coined the phrase. To the extent that commissioners have, at times, stated or implied otherwise (including, I have argued, in RIFO), Simington said, "It's partly people misspeak, partly they exaggerate, and, partly, you know, partly it's political."

But, he insisted, "I would distinguish between net neutrality regulation and Title II net neutrality regulation." I have pointed out that Title II (a very large telecommunications law from the 1930s) shaped the early years of the Internet. But, Simington argues, Title II was more or less withdrawn from broadband Internet Service Providers in 2002, and it has never been truly re-imposed. Improperly conflating "net neutrality principles" and "Title II" is one of the biggest reasons people misspeak or exaggerate about the history of Internet regulation, he contends.

Even under the 2015 Title II Order, Simington observes, the FCC didn't really re-impose Title II. Instead, the FCC enacted a few regulations it liked, justified them with very narrow fragments of the actual Title II, and then used the FCC's "forbearance" power to ignore the rest of Title II. The Democrat-authored Title II Order, Simington notes, imposed four rules... followed by around seven hundred forbearances. "Why exactly do you want to have Title II and then forbear everything?" Simington asks.

I agree, it's a fair question. It seems reckless to impose a whole statute, then ignore practically all of it, and then reshape the remaining powers to effectively write a completely new statute. In my "15 Questions for Republican Commissioners," I got pretty irritable at Republicans who evaded or ignored statutory text (we're supposed to be textualists!). However, if I ever write "15 Questions for Democratic Commissioners," I think I'd have some pretty pointed questions about obeying the statute for them, too.

My personal sense, from a conservative, separation-of-powers perspective, is that the FCC's job (like the job of the entire executive branch) is to "take care" to carry out the will of Congress, as expressed through the laws Congress passes... even when the will of Congress is kind of stupid. If negative consequences force Congress to reconsider, update, or even repeal the laws, so much the better. It is not clear to me that the "impose Title II but then forbear all of it" approach was even legal. Now, maybe you're reading this and you're a Democrat who isn't really into my originalist-textualist approach to law. But you know who is? The Supreme Court of the United States of America, which will ultimately decide on the legality of any FCC actions in this area.

But I digress. Back to the Commish. My next (pointed) question was about the text of the Telecommunications Act. I've contended that, like it or not, Congress pretty clearly intended for what we today call "ISPs" to be regulated as "telecommunications" providers under the authority of Title II, not merely "information" providers under the much lighter rules of Title I (and note: according to Verizon Communications Inc. v. FCC (D.C. Cir. 2014), Title I does not allow net neutrality regulation).

Here, Commissioner Simington agreed with a good deal of my historical analysis. He agreed that traditional ISPs did not, historically, own physical facilities; they "rode along" on top of existing telecommunications infrastructure. EarthLink provided DNS, email, and other internet access services over phone lines, but EarthLink wasn't building phone lines. Modern ISPs combine those facets of internet access: they send internet access services over cable and satellites and other physical infrastructure, and they own that physical infrastructure. We agree that is a real difference between the world Congress was regulating in 1996 and the world the FCC was trying to regulate in 2002 (and ever since) when it decided that cable Internet was subject to Title II.

But Simington pointed out, correctly, that the Telecom Act doesn't say anything about telecommunications providers being defined by their physical transmission facilities. So wasn't I sort of reading a "physical transmission facilities = telecom" clause into the statute without it actually being there?

I responded to this with a somewhat incredulous stare. "Isn't that a bit of wishful thinking?" I said. Congress had left undisturbed a then-60-year old regulatory structure that had distinguished between wireline operators and service providers in just the way I described. It had extended that regime using commonsense language whose legal and popular meanings at the time were understood to include this distinction. That regime had governed both "sides" of the Internet access industry since its inception, and it would continue to do so until the FCC changed the rules six years later.

True, Congress had not used the phrase "physical transmission facilities" in its technical definition of a telecom or an information service--but Congress had no way of knowing at the time that it would need to include that phrase as a prophylactic against a deliberate misreading by an executive agency bent on deregulation, half-a-dozen years later. So, when Republican commissioners make this argument, aren't they a little bit saying, "Here's what we want it to mean, and this reading supports what we want, so we're going to read it that way?"

The Commissioner chuckled and said, "If there's any regulatory agency in DC that doesn't have that as its bread and butter... but, that's not a defense," he considered.

Instead, Simington pointed to all the things that modern ISPs provide beyond the wired infrastructure: sure, there's DNS, and there's ancillary stuff like email and personal web pages, which I duly mocked in my Fifteen Questions article. But modern ISPs also need to provide a lot more than that, from the crazy complicated world of modern caching and CDNs, to malware monitoring, to DDOS defense. These aren't dumb pipes (even though edge providers like Google would really like us to see them that way, and even though the Obama Administration often painted them that way); modern ISPs are very intelligent, complex computer services that have a big information-processing component on top of the physical infrastructure. He suggests that, where I've really taken a stand against paragraph 38 of the Cable Modem Order (and what I consider its misinterpretation of the Stevens Report) the core logic that Republican FCC commissioners hang their hat on is paragraph 35.

Now it was my turn to concede a point: he's right! Modern ISPs are not simply dumb pipes. The information services they provide are truly impressive, and I shortchanged 2021 ISPs by quoting a document about their capabilities written in 2002.

But all that fancy stuff is undeniably running on top of dumb pipes, which the ISPs also own. In the Portland case, the federal courts resolved this the same way I would: by ruling that modern ISPs offer two services: a telecommunications "dumb pipes" service that is regulated under Title II, and an information processing service that runs on top of that, which is much more lightly regulated.

But the FCC, in its Cable Modem Order and all subsequent actions (except the 2015 Title II Order) has taken a much more creative route. The FCC says that the telecommunications service offered by an ISP is "part and parcel" of the information service it offers, and so can't be separately regulated, and so the whole package has to be considered an information service... largely immune to regulation.

No one has ever topped Justice Antonin Scalia's reply to this logic:

If... I call up a pizzeria and ask whether they offer delivery, both common sense and common “usage” would prevent them from answering: “No, we do not offer delivery—but if you order a pizza from us, we’ll bake it for you and then bring it to your house.”

The logical response to this would be something on the order of, “so, you do offer delivery.”

But our pizza-man may continue to deny the obvious and explain, paraphrasing the FCC and the Court: “No, even though we bring the pizza to your house, we are not actually ‘offering’ you delivery, because the delivery that we provide to our end users is ‘part and parcel’ of our pizzeria-pizza-at-home service and is ‘integral to its other capabilities.’ ”

Any reasonable customer would conclude at that point that his interlocutor was either crazy or following some too-clever-by-half legal advice.

And Simington, recognizing the pizzeria analogy before I actually quoted it, agreed that this was perhaps "not the most principled form of reasoning"—but, he asks, hear him out.

If you don't make the, ah, creative leap that Scalia describes, then Title II regulation of all modern ISPs is, arguably (and, oh my, they will argue!), a foregone conclusion. ("Yes," nods I, "as Congress intended.") And where does that take us?

When Title II imposes, say, local loop unbundling on cable providers, do we get back to the 1990s, where college kids ran commercial ISPs out of their dorm rooms in direct competition with the bigs? Probably not. More likely, it seems to Simington, Amazon and Google would immediately become America's new ISP oligarchs. I had to admit that had never crossed my mind.

But it makes sense: Google's computing power alone exceeds that of most countries. They used 12.4 terawatt-hours of energy in 2019, which puts them ahead of more than half of all countries on Earth simply on electricity use... and Google isn't spending any of that powering cities. It's powering servers. Meanwhile, Amazon's dominant cloud computing platform (which I use every day at my job) is efficient, flexible, infinitely scalable, and they've probably got a data center in your back yard. Let these guys into the telecom networks through local loop unbundling to offer competing ISP services, and it's a good bet one of them will corner that market by Christmas. "We may well yearn for the 'good old days' of today's ISPs, in a certain sense," said Simington. (And local-loop unbundling is just one facet of Title II regulation!)

I chickened out and said, you know, Amazon and Google are such bloated companies anyway that, well, "maybe at that point it's the FTC's problem." Then I heard those words coming out of my mouth, thought I'm a hypocrite! and tried to make a larger point: We live in an age of Titans. You've got this internet Titan over here and that telecom Titan over there and they're punching each other, and the rest of us are down here trying to build our little livelihoods in their shadow without getting punched or trapped under a falling Titan ourselves.

In a world of Titans, opening a market to competition (such as last-mile internet access services) typically means letting more of the Titans punch each other. It's competition, but not the sort of entrepreneurial mom-and-pop stuff Americans dream of.

Simington liked this image, and described a dark future, one that has already existed in some places and times. It's a world where there's like five major banks, a few telcos, some major insurance companies, everyone sits on one another's boards, they all went to the same expensive private schools... and, between them, these insiders have got the capital markets sewn up. Which, in turn, gives them the ability to bully everyone in negotiations, refuse to innovate, and just generally sit on their hands.

As enmeshed as it is here—and it is; our last two FCC chairmen worked for telecoms or their trade organizations prior to the FCC—Simington insists that it's a lot better here than it could be. Title II, in his view, risks ushering it in. (And, well... I can't disagree! Title II contemplates government regulation of telecom monopolists. Is there any situation under the sun where the danger of regulatory capture is greater?)

And yet... it's what the statute says. Should the unelected FCC be protecting us from gaps in Congress's logic? I don't think that's what we put Republican officials in office for. And the nice thing about writing the blog post after is that you get to give yourself the last word!

But, seriously, by this point, we'd already been talking for nearly our entire half-hour, and we were still hammering out my first few questions about the law. So we put a pin in it and shifted gears to a different topic: gatekeeping!

My Next Few Questions: Gatekeeping

I wrote in my "Fifteen Questions" that Commissioner Simington had broken down the motivations for net neutrality into three boxes: the monopoly problem, the gatekeeper problem, and the minimum standards problem. I then argued that these were all facets of the monopoly problem. Therefore, you wouldn't solve the gatekeeper or minimum standards challenges without either a competitive market or (if we determine that no competitive market is forthcoming) government regulation.

Simington took this in an unexpected direction. He pointed out that the logic of the Title II Order, as built out by then-Chairman Tom Wheeler, really proves more than Chairman Wheeler probably would have wanted (or had jurisdiction to ask for).

The logic that powerful gatekeepers can prevent certain web content from reaching me (or cut me off altogether) does indeed apply to an ISP, including my ISP: Comcast. If Comcast just turned off my Internet connection one day, it would indeed make my life much more complicated. However, Simington suggests, I'd have some alternatives. Simington, like most Americans, switches broadband Internet connections several times a day anyway: from his home hookup, to the free WiFi at Starbucks, to an AT&T hotspot along the road, to his workplace hookup. All along, he has internet access through his phone, running at speeds that would make a power gamer in 2001 with a dedicated T1 line weep with joy.

Of course, that doesn't eliminate the difficulty and distress it would cause for an ISP to just decide it doesn't want you as a customer anymore one day. Your ISP really is a gatekeeper, for several of the reasons Wheeler laid out in the Title II Order.

But that logic applies even more persuasively to various online services. Simington has had an Amazon account since the late '90s, through maybe ten residences. If Amazon decided to ban him, that would have a much bigger effect on him much more quickly, with fewer viable alternatives—and he would have absolutely no alternatives for watching Amazon Prime exclusive content like The Expanse.

I'll disclose to you now, reader, that this worries me a great deal, too. I recently purchased an Oculus Quest VR headset. I've put probably five or six hundred dollars into hardware and games at this point—which, for a dad with two kids paying Catholic school tuition, is the biggest completely personal splurge I have made in literally three or four years—and I adore my headset. However, my Quest is also tethered inexorably to my Facebook account. If I am ever banned from Facebook, my Quest becomes a brick, and there's nothing I can do about it. My hundreds of dollars, not easily come by, would be gone forever.

I have, for years, maintained a really healthy right-leaning political discussion group on Facebook, with civil discourse from many perspectives, but, ever since I got my Quest, I've been thinking of shutting it down... and I already have stopped discussing certain public policy topics because Facebook's banhammers seem to be especially hammery on those subjects, especially if you express the conservative perspective on them. (Alas, we all know from the lab-leak controversy that, for Facebook's censors, the truth is no defense.) I am indeed much more worried about Facebook on a daily basis than I am about Comcast!

That's where the logic of the Title II Order seems to point, Simington argues, whether it intended to or not.

I would have loved to spend the next hour with him teasing out the implications of that logic and what it means for companies like Google and Amazon and Facebook at the FCC (are we talking about Title II-like regulation of Twitter??)... but we didn't have an hour, we didn't even have five minutes, so we had to jump back to the matter of ISP monopolies with this region unexplored.

My Last Questions: The ISP Natural Monopoly (?)

My whole argument for net neutrality regulation and Title II depends on the premise that modern ISPs are natural monopolists. That is, they operate in a utility-like market that tends toward monopoly, many of them are already monopolists in some markets, they are oligopolies in most of the rest, and there is basically nothing we can do to prevent them from gradually consolidating into a either single giant ISP blob (like Ma Bell) or regional ISP monopolies (like 19th-century railroad monopolies). Either way, ISPs either have price-making power (and other market power) now, or they will inevitably acquire (or increase) it in the future.

If that's wrong, then my argument for government-imposed net neutrality regulation collapses.

Commissioner Simington never critiqued my fundamental position that the modern ISP market fundamentally works like a utility market. (To be clear, it's entirely possible that he disagrees with my view; all I'm saying is that, in the few minutes we had to talk, he didn't critique it.) But that didn't mean we agreed. I think it's fair to say that, where I take a glass-half-empty view of the situation, Simington takes a glass-half-full view. We didn't dispute the underlying facts very much, but we saw those facts in quite different lights.

For example, when I look at ISPs, I see a market that is gradually but inexorably contracting. Broadband competition is completely static in many (most?) residences, including mine (as I've disclosed). It is monopolistic in many places, an oligopoly in most others, and—while it has been a few years since the Time-Warner-AT&T merger—the industry shows no sign of reversing course.

When Commissioner Simington looks at ISPs, he sees a market that may be contracting but hasn't gotten there yet. Comcast and CenturyLink, out in my neck of the woods, still appear to be tussling rather viciously for customers (rather than colluding to set higher prices, as real oligopolists do). And Comcast doesn't just have to worry about CenturyLink; they're also fighting off Verizon, T-Mobile, and AT&T (although, point for my side, RIP Sprint), and new technologies are on the horizon that threaten Comcast as well. ISPs may not be as competitive as the commodities markets, but they're a lot more competitive than, say, Canada's ISPs. This is the same general thrust as the Restoring Internet Freedom Order, paragraphs 117-139... and, as I said in "Fifteen Questions," it's the part of RIFO I found most impressive. As Simington put it:

When Alexander Graham Bell ran his first phone line and managed to get his first message across, we wouldn't have rushed to the offices and said, "Bell, you now have a new terminating monopoly between two rooms!"

Speaking of those new technologies: when I look at the new technologies being rolled out, I see a promise now almost twenty years old, repeatedly made by optimistic FCC commissioners, that competition for home broadband connections was just around the corner. And it never was.

Simington told me that, a year ago, he would have found my doubts very strong, maybe "irrefutable." But SpaceX's Starlink, in his view, was a real game-changer... and now Kuiper and OneWeb are right behind it. He's got tribes telling him that even prototype low-Earth orbit (LEO) internet services have taken them 25 years into the future. He's got Alaskans telling him that if he does anything to the LEO satellite programs, they'll have their Congressmen picket his house. So, when Simington looks at new technologies being rolled out, he sees this one as really truly just around the corner. This is a big bet, but it's a bet that has started delivering real, life-changing results to actual customers. We'll see how it plays out.

Speaking of seeing how it plays out:

When I look at bad behavior by ISPs, I see inevitability. The ISPs started engaging in bad behavior very soon after getting out from under Title II regulation (I listed some in my previous articles and won't reference them again here). The bad behavior stopped when they were re-regulated (although to what extent the new regulatory regime was "Title II" is a matter for further discussion). It has not restarted again, in my view, only because they have been under more or less continuous legal threat since RIFO: first from the federal courts in Mozilla v. FCC (which could have overturned RIFO); then from the states, which have begun passing their own net neutrality laws; and now most recently from the Biden Administration, which seems inclined to give the Electronic Frontier Foundation whatever it wants.

But take those threats away, and I think we go right back to Verizon grabbing Netflix (and smaller platforms, like my webhost) by the lapels and saying, "Hey, be a shame if you could never reach our customers again, wouldn't it? What are they worth to ya?" just like seven years ago.

On the other hand, when Simington looks at bad behavior by ISPs, he points out that the last bad thing I can come up with was seven years ago. He read an interview Sen. Markey did with The Verge. Markey is a big net neutrality guy from way back, and the very sympathetic Verge interviewer asked, well, what's all the bad stuff that's been happening now that Trump's FCC repealed Title II regulations? And Sen. Markey was forced to admit, well... there hasn't been any bad stuff! Not yet! But you wait and see all the bad stuff they'll do now that Mozilla v. FCC has let them off the leash!

So Simington's, like, okay, why don't we wait and see? Where I see inevitability, Simington sees something that hasn't happened yet.

And, you know, I have to admit, he has a point. Seven years ago, when I wrote my pro-net neutrality piece, bad behavior by ISPs was real and worsening. I can't really overstate how alarming I found the Verizon-Netflix fight, once I dug into the details and discovered just how dishonest Verizon was being, and I published my net neutrality post soon after. But, here in 2021, ISPs aren't doing anything (that I know of, anyway) that makes net neutrality regulations urgent like they were in 2014.

In my 2014 post, I did present some arguments for a wait-and-see approach, but found them quite weak given the facts on the ground. Those arguments are undeniably stronger today. After all, if the FCC decides not to regulate right now, and Comcast redeploys Sandvine, the FCC can always just decide to regulate then. Heck, maybe setting that Sword of Damocles over them will teach the ISPs to keep themselves in line without government intervention!

Ha ha ha, I crack me up. I do not share that optimism about ISPs. But, I have to admit: I could be wrong about them. It might not play out the way I expect. And, with a full four years left in the Biden Administration, it wouldn't cost net neutrality advocates very much to wait and see, either.

Towards Title II Anyway

Despite these philosophical musings, the political reality, in my opinion, is that Title II is on its way. Not only will the Biden FCC soon have the votes to impose it with or without support from Messrs. Simington and Carr (the other Republican commissioner), but, despite a continuing (very strong) stance against Title II, the ISPs face some tough incentives to make it work, and some will even see some silver linings in it. Why? Because states are passing net-neutrality laws of their own, and one of the straightforwardest ways to escape a national patchwork of differing, complex legal requirements is for the FCC to impose a single national standard... which, in the absence of Congressional action, has to be done under Title II. (Industry—like pretty much everyone else—would prefer Congressional action, but that's not going to happen, so federal regulation is probably the next-best option.) Frankly, this dynamic worries me: when industry asks to be regulated, you should go to Double Red Alert, because regulatory capture is their next play.

So whatever our larger policy commitments, I think everyone is going to have to start trying to figure out how to implement Title II regulation in a manner that both reflects the intent of the statute and promotes the best possible Internet policy for the United States of America. I asked Simington how he would approach this problem (even though it wasn't one of my original Fifteen Questions).

If Title II is as inevitable as I say, says Simington, then he will work hard to at least round off the "rough edges" as best he can. The key, for him, is that the forbearance power needs to be used better. There are risks from using forbearance improperly (especially if a court comes along later and strikes down parts of forbearance) that are simply not worth taking, because this is how you might get, say, Amazon as The ISP Of Doom. Some of the bigger forbearances may really need the blessing of Congress... although I'll point out that the other option is to not forbear those items at all. It's always an option to just carry out Title II and dare Congress to fix it. (But, sure, asking Congress before the fact works, too.)

Also, Simington is very concerned about laying heavy regulatory burdens on small operators. Although marginalized, small-business ISPs are out there, represented by tiny trade groups like WISPA, and they are much more vulnerable to sloppy regulation than the big telcos. To the extent that the regulatory burden on them can be shrunk or removed, he wants these mom-and-pops protected.

I must agree that Republican commissioners, with their great sensitivity to the ways in which even legitimately good regulations harm businesses, are in the best possible position to help that happen, and I hope that the FCC is able to effectively thread this needle. A guiding principle for all regulation should be that regulatory agencies must work very very hard to make it very very easy for regulated firms to meet their legal obligations (while still fulfilling the regulators' oversight goals). Heavy regulatory burdens help large companies (especially monopolists) and hurt small businesses, period. Compliance costs are a business tax that disproportionately hurts the poorest mom-and-pop businesses.

Yet sometimes, in Washington, the arrow seems to be reversed: regulatory agencies force regulated firms to work very very hard to fit some Microsoft Word template or something, in order to make the agency's job easier. My sisters both write grant proposals for a living, and some of the government agencies they work with drive them up the wall with their ticky-tacky requirements for "bid submissions." The biggest regulated firms are only too happy to encourage this agency behavior, since it keeps their upstart competitors down. Republicans are (in my experience) typically more aware of this dynamic, and can do a great deal to counter it.

And that's where we ended! It was a great conversation, and I'm glad to be able to bring it to you, my dozen readers. It would have felt like malpractice to publish "Fifteen Questions I'd Ask a Republican FCC Commissioner," ask a Republican commissioner those very questions, and then not tell you the answers.

However, fair warning, if I ever get the chance to talk to Nathan again (over the phone or over my pasta carbonara), I expect it to be entirely informal, and I don't expect to blog about it.