How the National Debt Will Destroy Us, In Plain English

Sovereign debt is more complicated than family credit-card debt. But not THAT much more complicated.

This is an attempt to explain the national debt (and its dangers) in a way anyone can understand, so share away. Naturally, I skip past some of the complicated parts, and I tried to keep anything technical in footnotes.

It’s easy to understand how credit-card debt can destroy your life: you just run out of money.

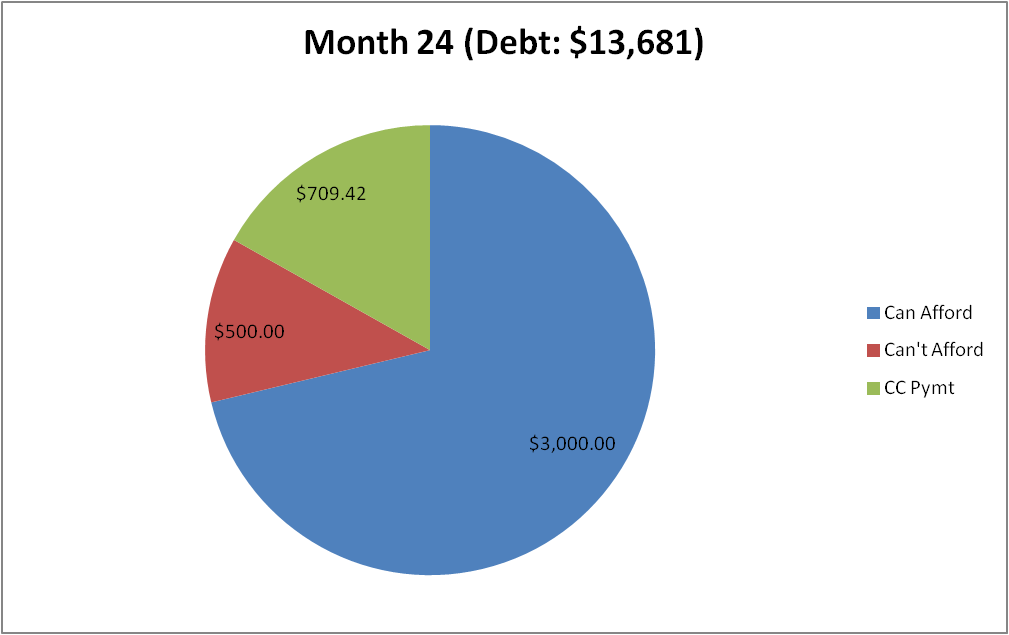

You start out with a small imbalance in your budget: you’re making $3,000/month, but spending $3,500/month. Rather than cut expenses, you put the extra $500 on a credit card every month, with a 18% annual interest rate, and start making minimum payments—which is only $25, the first month. That’s not so bad! So next month you put $525 on your credit card. The month after, $550. Then $576. (The extra dollar is interest.) And so on.

But, after two years of this, you have $13,000 in credit card debt, and your minimum monthly payment is $709 — which is more money than you’re actually getting out of the credit card to help pay your actual monthly expenses!

Finally, you realize, you have to cut your expenses and live within your means. You reduce your expenses to $3,000/month. But, alas, it’s too late: your debt has taken on a life of its own, and you find yourself going deeper into debt just to pay the debt you already have. A year later:

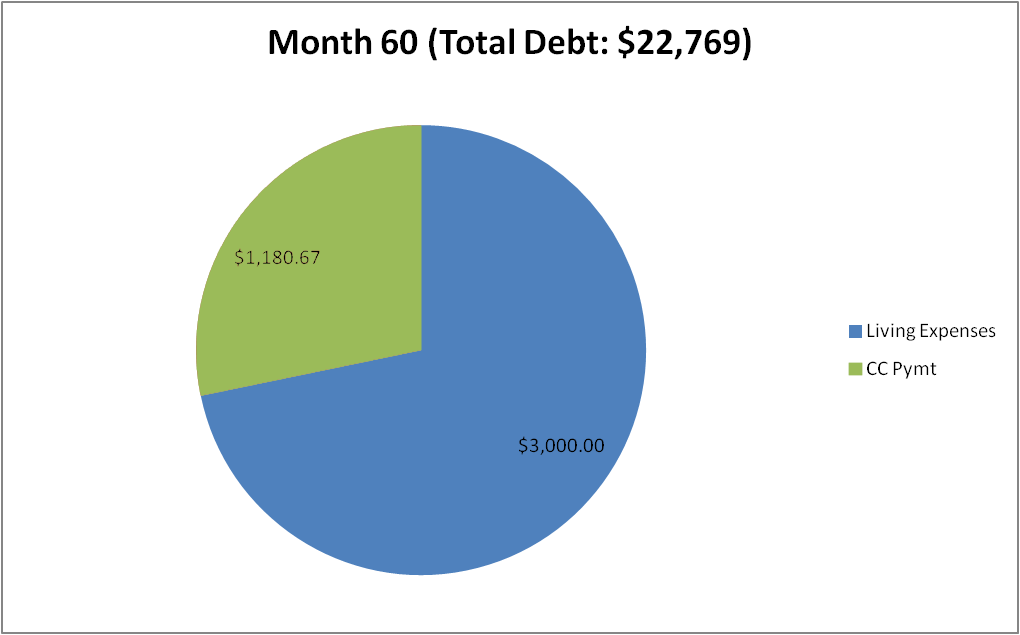

You’re still only paying the minimum every month—it’s all you can afford. The big cuts you’ve already made simply aren’t enough anymore. Unless you can cut your expenses even deeper (or get a big raise at work) and put everything you have into fighting your debt, it will just keep growing. After five years, you’ll spend more on your credit card minimum payments than you spend on rent:

By Year Eight, you’re bankrupt.

Millions of Americans make this juggling act work for a while, but, unless they cut their expenses drastically, the credit card company eventually demands a higher minimum payment than the family can possibly afford. Bankruptcy court then cuts their expenses forcibly. A family has to live within its means, tightening the belt in tough times. “Act your wage!” Don’t spend more than you earn. Those are clichés because they are true.

The United States Can’t Run Out Of Money

People naturally apply that logic to their country. If the country spends more than it receives in taxes, it’s probably going to get into trouble, right? Politicians posturing as deficit hawks use lines like “Washington should have to do what millions of Americans have to do every month at the kitchen table!” because it’s easy to understand (and easy to get mad about).

But it’s not that simple. The United States of America does not have to live within its means, because it has something your family doesn’t have. It has something even other countries don’t have: a printing press that makes U.S. Dollars. The government can’t run out of money. It has a system.

When the U.S.A. doesn’t have enough money to pay its bills, the U.S. Treasury borrows money (called “bonds”)1 from investors. Investors include foreign governments, mutual funds, pensions, insurance companies—and even other parts of the federal government, like the Social Security Trust Fund:

We’ll eventually have to pay all those people their money back, plus a small amount of interest. We normally pay back our bondholders back by selling more bonds. Then we use that borrowed cash to pay off the original lenders. This is kind of like paying for a credit card bill by getting a new credit card and putting the bill for the old card on the new one.

When a family takes out a lot of loans, lenders start to worry that the family won’t be able to pay the loan back. So the family’s credit score goes down, and lenders demand bigger interest payments, to balance the risk of default. It’s the same with the federal government. As the government takes out more and more bonds, lenders who buy bonds demand steadily higher interest rates.

Suppose we sell Peter a $500 bond at 3% interest. A few years later, we owe Peter $515 in cash. We get that cash by selling Alastair a bond for $515. Seeing what we’re doing, Alastair demands 5% interest for his loan. Higher interest means that, when it’s time to pay back Alastair, we owe him $525, not $515. We raise that money by selling a loan to Peppa for $525… only she demands 7% interest. Now we’re on the hook for $535. Even though we only took out $500 to begin with, our minimum payment is inching upward.

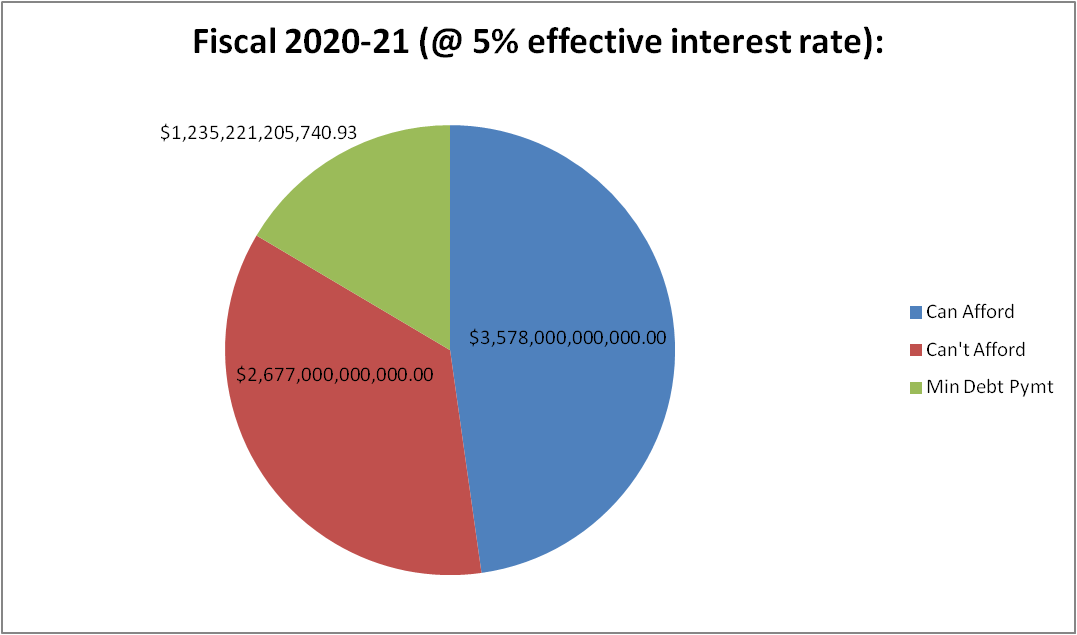

Starting to sound like our household credit card debt crisis? It should. Here’s a pie chart for the federal government in fiscal year 20202:

…but not to worry! Here’s where the printing press comes in!

The Federal Reserve (a quasi-independent agency that controls the printing press) manipulates the interest rate for Treasury bonds.3 This manipulation is not a secret and is perfectly legal. It’s a big reason why the Federal Reserve (aka “the Fed”) exists.

The Federal Reserve manipulates the interest rate by printing money and giving that money to banks, financial firms, and rich people in general. (The details are extremely complicated.4) Interest rates for everyone are determined by how quickly the Fed is giving fresh money to banks at the moment. So, if the Fed wants lower interest rates, all it has to do is print more money and give it to banks faster.

This puts the U.S. Treasury in a unique position. It’s kind of like if you controlled the interest rate on your credit card debt. “Oh, that debt is growing too fast!” you would say. “Let’s just reduce that interest rate from 18% to 3%! That should take care of it!” It would work, too. If your salary went up even a tiny bit, just 1% per year, your credit card debt would grow slowly enough to remain manageable until your increasing income overtook it. You’d pay the debt off in a few years.

For the past ten years, that’s been the U.S.A.’s basic strategy for our national debt. Since the crash, the overall U.S. economy has been growing about 2% every year, which means the Treasury is collecting about 2% more in taxes every year. So, as long as the Federal Reserve can keep interest rates below 2%, we can keep selling bonds forever, because our economy will grow fast enough to generate new tax revenue to pay the bonds off.

Sure, the total national debt is huge and getting huger, but who cares? Debt is just a number. As long as we can make our minimum payments, we’ll be okay. And as long as interest rates stay below our economic growth rate, we can make those payments.

Sure enough, since the financial crisis, the Fed has helped keep the interest rate on a 10-year bond at approximately 2.3%.5 That’s low enough. At today’s interest rates, our economy is growing roughly fast enough to keep pace with the size of the debt. Today’s interest rate is much lower than it was during the prosperous 1990s and early 2000s. (It was about 6% back then.)

This seems like a pretty sweet deal! If the economy can grow fast enough to cover the interest, it seems like maybe the Treasury can borrow infinity dollars to pay for infinity government programs. When the Treasury has to pay it back, they just borrow even more, counting on the Fed to keep printing enough new dollars to keep interest rates low. Now that I’ve spelled it out, why aren’t we doing this? If we can print as much money as we want, why don’t we just print enough money to pay for all healthcare and make all college free and rebuild all our bridges and maybe give every American $10,000 just for funsies?

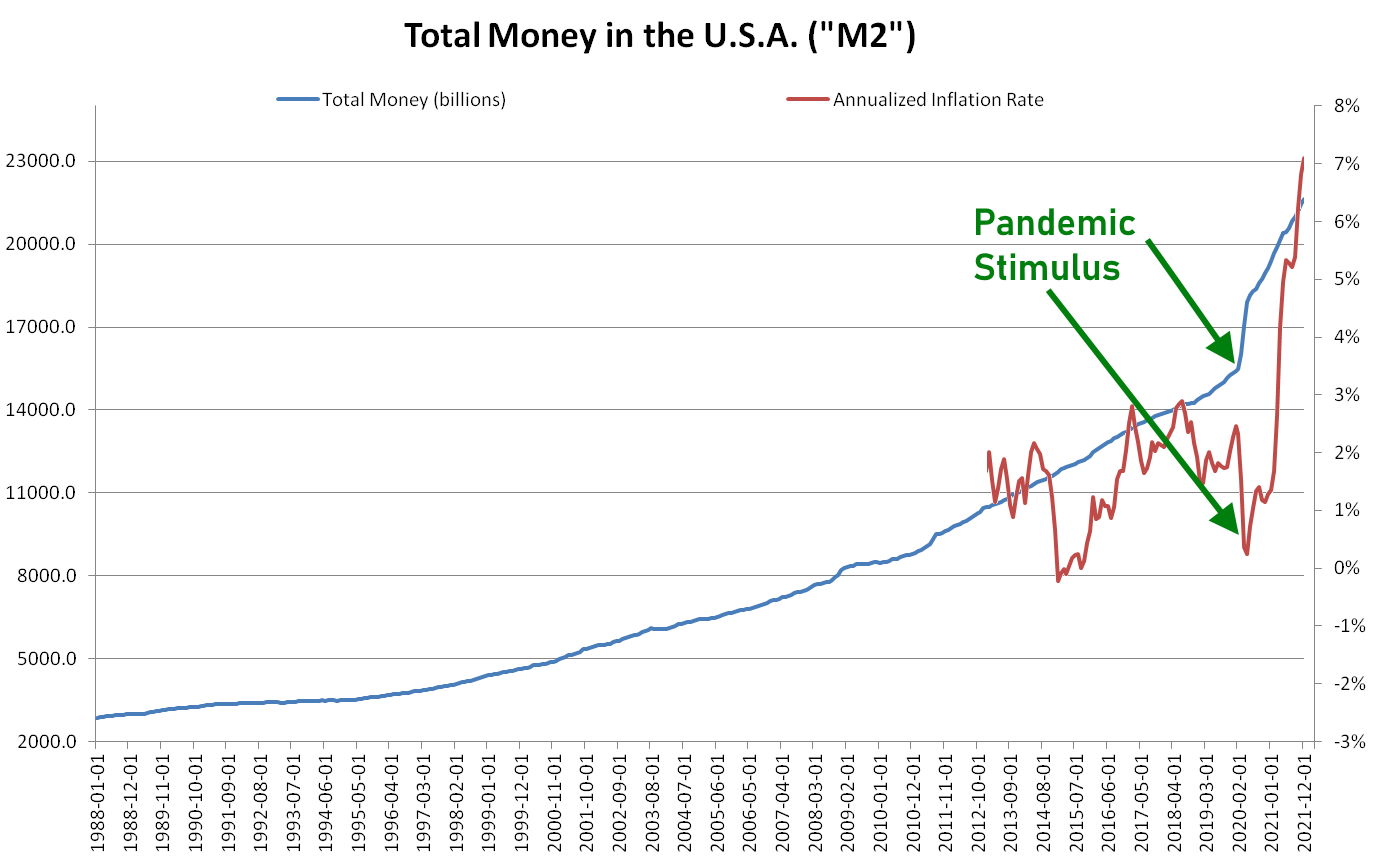

Because of inflation. The federal government stopped believing in inflation after 2010. So did many economists. Many ordinary people started thinking of inflation as “that thing that happened in the ‘70s, right?” But inflation has finally returned, and, with it, my ability to write this article convincingly.

Inflation happens whenever the Fed prints money and gives it to someone.

How Inflation Works

Suppose you’re selling a used car. Kelley Blue Book says you should be able to get $4,900-5,100 for it. You want to get the best price, though, so you sell it in an auction on eBay. After a dozen bids, your car sells for $5,000.

But now suppose that, on the last day of the auction, the Federal Reserve called several of the people bidding on your car—people who really need a car—and gave each of them a bag with $3,000 in cold hard fresh-printed cash inside. Some of them might take that $3k and start bidding on other, more expensive cars. But one of them, who has already decided he wants your car and doesn’t want to do more research, might just say to himself, “Huh, I couldn’t really afford to buy this car for more than $4,950 this morning. But now… how about I go ahead and take this bid to $5,100?” And then the next gal says, “Y’know, I have a bag of money, I can afford $5,200.” And so on. It’s plausible that your car, worth only $5,000 this morning, will now sell for $6,000 or more, all thanks to the money the Fed injected into the auction!

Now imagine that happening to every single thing people buy, both final goods (like the corn you buy at the grocery store) and inputs (like the fertilizer used to grow the corn). Prices go up across the board. That’s what happens when the Fed tosses new bags of money into the economy. That’s inflation.6

Every single time the Federal Reserve prints a new dollar without an old dollar being destroyed, it causes just a teensy-tiny bit of pressure on prices to start inflating. In fact, the Fed deliberately causes some inflation (usually around 2% annually) because a small, steady amount of inflation gives the Fed some tools to prevent recessions and promote recoveries. Inflation also has a certain amount of inertia to it, so it takes quite a lot of dollars to start moving the needle. Once the needle starts to move, though…

Well, you’ve seen the headlines:

To Fight Inflation, Interest Rates Must Rise

High inflation is bad. Costs go up at the grocery story, and, even if ordinary people get small cost-of-living increases at work, it’s never enough to keep up with inflation.7 Regular people fall behind.

As you’ve probably noticed, we live in a time of high inflation:

Since inflation is caused by the Fed printing too much new money,8 the solution to inflation is really quite simple: the Fed has to print less money. It doesn’t have to stop. It just has to slow down.

However, remember: the Fed keeps interest rates low by printing more money. When the Fed prints less money, interest rates go up.

Rising interest rates can cause all kinds of problems. In 1981, the Fed raised interest rates dramatically in order to stop double-digit inflation. It caused a major recession. But we aren’t interested in that. We’re interested only in the effect on the national debt.

If the interest rate goes up, we’re going to have to pay more interest on the national debt.9

Now the credit card crisis arrives.

Line Goes Up

Remember this chart? It’s a chart of U.S. federal government spending last year:

The blue area is stuff we actually paid for, using actual money collected through taxes. The red area is stuff we couldn’t pay for, so we borrowed the money. The green area is the interest payments on our debt. We couldn’t actually afford to pay that interest, so we also borrowed that money (borrowing from Peter to pay Paul) and counted on the Fed to print enough money to cover our costs.

That chart is how it looked when the rate on a 10-year Treasury bond was a mere 1.5%.

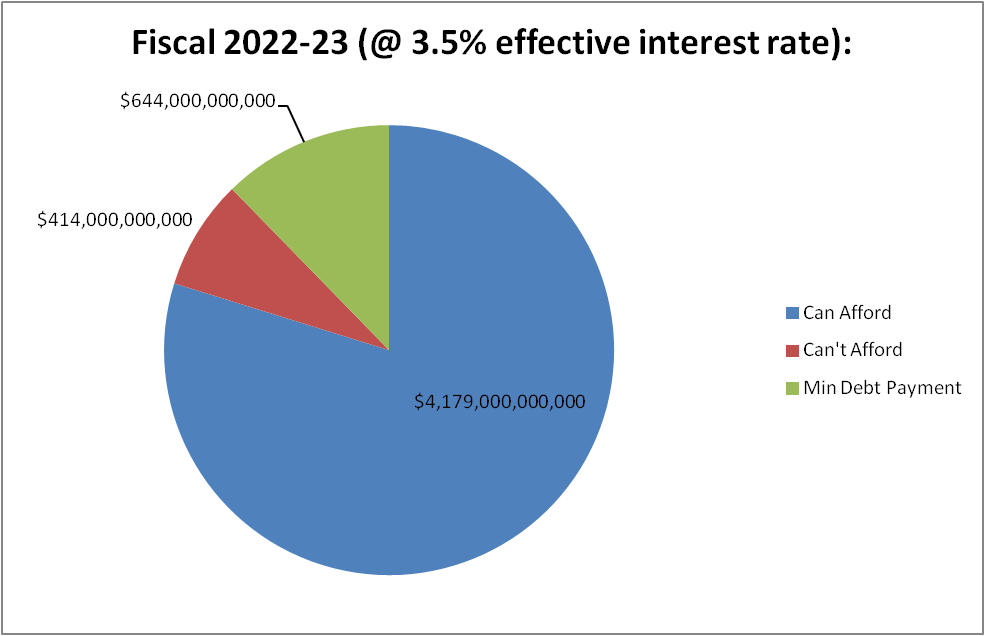

Here’s how this same chart would have looked if interest rates had been a modest 5% instead:

The debt payments, at this point, are large enough to become self-sustaining. If our interest rates go up like this, we will gradually have to devote more and more of our budget to just paying off the interest. Even if we cut our excess spending, it wouldn’t be enough to stop the growth of the debt payments. They will have taken on a life of their own.

Of course, we absolutely will not cut our excess spending. Oh, sure, we’ll end the dramatic, over-the-top pandemic spending of 2020. But actually balancing the budget would mean smashing Medicare to pieces and eliminating the majority of the U.S. military. (Yes, both.) We ain’t gonna do it. So our debt payments will keep growing, faster and faster.

It’s extremely difficult to find out exactly how much faster. It’s a complicated piece of math, and depends on a lot of assumptions. The U.S. government mostly makes very optimistic assumptions. For example, the Congressional Budget Office currently believes that the Fed will keep interest rates close to zero through 2031. I think it’s safe to assume their assumption is wrong. Prediction markets currently believe the CBO’s sunny estimate for 2022 is off by a factor of 8 — and that’s only looking 10 months ahead, not 10 years.

I spent a great deal of time with the Congressional Budget Office website over the past several days, and I managed to figure out what this picture looks like with a little less sunny optimism.10

Instead of assuming that interest rates stay low forever, let’s instead assume that the Fed’s response to inflation sharply drives up interest rates. The interest rate on a 10-year Treasury bond goes to 3.5% this year, 5% in 2025, and 10% in 2030. These are all pretty plausible numbers, well within historical norms. They may even be optimistic. During the early-1980s fight to end stagflation, the interest rate went above 10% and stayed there for six years. (It peaked at 16%.)

So here’s what the next few years look like, assuming interest rates sharply rise to combat inflation (and assuming the CBO’s other projections are correct).11 Watch how the green wedge grows to take up more and more of the budget:

Every time we pay off the green wedge, we have to take out more bonds, making the green wedge even larger the next year. How long can we keep this up?

The National Credit-Card Crisis

This looks a whole lot like the credit card debt crisis we considered at the start. That’s because it is, by 2030, a national credit card crisis. We end up borrowing more money to pay for our own borrowing than we borrow to pay for actual stuff we actually want. And the borrowing costs only grow, after this point, until we reach the point where we can’t pay anymore and have to declare bankruptcy.

That is how the national debt destroys us. It’s not the size of the debt. It’s the size of the interest payments. Those interest payments have been held at bay for years by the Federal Reserve’s money printer, but, if that money printer has to slow down, interest will be back with a roar, and it will gradually swallow our entire budget whole.

It is possible that won’t happen this decade. Inflation may be whipped more easily than expected. The War On Prices could be won by Christmas, and then the Fed can quickly turn on the printers again full blast, like a national morphine line. We’ve kept juggling these balls for four decades now. Who’s to say we can’t do one or two more?

But, eventually, the music stops. Eventually, the fiscal crisis starts. Eventually, our debts must be paid.

What Can Be Done

Once we’re in the fiscal crisis, we then have four options:

Cut interest rates back down below 2%, so our borrowing costs at least stop growing.

Bad consequence: inflation runs rampant, and bond-buyers might not even accept this once the fiscal crisis starts. Once they see our weakness, they may demand higher interest rates from the Treasury regardless of Fed policy.

(Also, it just might be possible that the Fed’s system of “giving free money to the richest people in our society in order to make our debts affordable” will become politically unpopular in the future. It’s kinda weird that isn’t unpopular now, but I think most people just don’t know this is how our finance system currently works.)Cut expenses. Balance the budget. Use the surplus to start paying down the debt.

Bad consequence: Medicare and the U.S. military more or less shut down.Raise taxes (on everyone, not just the rich, and by a lot). Balance the budget. Use the surplus to start paying down the debt.

Bad consequence: higher taxes slow the economy, which means we have to raise taxes by even more than we first expected, which slows the economy even more, which… (and so on).National bankruptcy. Default on some of our debts, renegotiate others, and resize the national debt by fiat.

Bad consequence: well, for one, under the Validity of the Public Debt clause, it may be unconstitutional to do this intentionally.

Also, the U.S. defaulting would destroy the world economic order—one that benefits everyone, but benefits America especially much. Nothing like it has ever happened before, so no one knows quite what would happen, but economists speak of it in hushed tones like Ragnarok.

The first three options are politically impossible. Nobody will accept permanently high (and rising) inflation, nobody will raise taxes on the middle class, and nobody will make bone-deep spending cuts that would leave millions of voters screaming.

In a functional body politic, we’d compromise between the three and we’d all be able to live with it. In reality, I expect that we’ll end up choosing Door #4 and default on our debt. We might talk ourselves into it, convincing ourselves it will be okay. Or we might just wake up one morning, halfway into one of our increasingly routine debt limit battles, and find out that, oopsie, we defaulted by accident. During a debt limit crisis, the Treasury pays the bills on an emergency basis based on extremely complicated math and a lot of fancy guesswork about exactly how much money they’ll receive from taxes each day. It would be all too easy for them to make a mistake and find the Treasury empty when debtors come calling and, boom, global economic catastrophe.

One way or another, American civilization will come through the crisis to reach the other side. Time’s arrow will see to that, if nothing else. But, when the conditions are ripe, the fiscal crisis has all the makings of a national paroxysm on the order of the Iraq War or the Great Recession.

And there is nothing, absolutely nothing, you can do to head off this crisis. I mean, in theory, we could start making these changes now, so the budget eventually balances and the debt eventually starts shrinking. But there is zero political support for that in the United States.

Elected Democrats openly admit that, not only don’t they have a plan to fix the debt, they actually want to expand it a lot more, to help pay for more programs! Right now, they are incandescently furious at Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) for blocking a multi-trillion dollar bill because the economy is still reeling from the inflation caused by their last few multi-trillion dollar bills. Manchin’s their best hope of re-election, and they hate him for it.

Elected Republicans are happy to criticize Democrats’ big-spending ways… until they actually wield actual power, at which point the GOP becomes just as bad as the Democrats! Three of the biggest contributors to our broken pattern of spending and borrowing were named Reagan, Bush, and Trump. Republican voters reward this. Indeed, one of the big underappreciated reasons why Trump won the 2016 primary was that Trump was the first GOP presidential candidate in decades to stop pretending he cared about the debt. He vowed no cuts to Social Security, no cuts to Medicare, and big cuts to the taxes that pay for both… and, hey! Promise kept! Fiscal disaster, thy name is the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017!

Financial titans and the captains of industry could theoretically exert pressure on Washington to get its debt problem under control. But they won’t. The bond vigilantes of yore are apparently all dead, and the current Boomer-run financial industry is too focused on next quarter’s returns, too happy with its bags of free money and inflated stock prices to lift a finger against the Fed. In some ways, that’s a good thing. “The rich run the country” has been a powerful subtext in American political discourse for a long time. If that subtext became text, that might be clarifying, but also very dangerous to our political order for a whole host of other reasons.

So you’re out of luck. Ross Perot and Paul Ryan warned us, but the crisis is coming sooner or later, and no one is going to stop it.

So hope it comes “later,” and… I dunno… Buy gold?

Next Time at De Civitate: I’m long overdue for a new installment of Worthy Links. I have a ton of good ones saved up to curate for your reading enjoyment

However, Worthy Links is a paid feature now—just about the only thing on De Civ with a paywall, but, with all this inflation going on, we gots bills to pay!—so, if you want to see all the neat stuff I’ve been reading, you may want to upgrade to a paid subscription. I’ll make it worth your while:

Technically, short-term bonds (0-52 weeks) from the U.S. Treasury are called “T-Bills,” medium-term Treasury bonds (2-10 years) are called “T-Notes,” and only long-term Treasury bonds (10-30 years) are actually called “T-Bonds.” But this is just financial jargon. They’re all Treasury bonds.

If you are a huge federal budget nerd, you may look at this chart and go, “Wait! $523 billion on the debt?! But our net interest payment for Fiscal 2020-21 was only $343 billion!” True, but we don’t care about net interest here. Interest revenues are simply revenues; they go toward stuff we can afford and are counted in the blue part of the chart. We care about gross interest. The Treasury helpfully lists exact numbers for gross interest, although I used the CBO’s rounded numbers for the sake of a clean chart.

…and the interest rates for everything else in the economy, from mortgages to the interest rate on your savings account at the bank. But we don’t care about all that today. This article is just about the national debt and how the Fed influences it.

They don’t even actually physically print the money anymore. The Fed just adds zeroes to a bank’s account in a computer system. It works just like a printing press, but with all the cool parts (the “printing” and the “press”) taken out.

The Fed tried raising rates around 2018—much to President Trump’s fury—but they only made it to 3.3% before the economy freaked, the Fed chickened out, and the interest rate dropped back to roughly 2%.

There is a dispute between Milton Friedman’s monetarists and John Maynard Keynes’s neo-Keynesians about whether money-printing is the sole cause of inflation in a modern fiat economy, or whether it is only one of several causes. There is also a dispute between those camps about how to define inflation, which accounts for much of the disagreement in the first dispute. This article brackets the whole question of cost-push inflation and other non-Fed causes of inflation, because we only care about inflation here insofar as it impacts Fed policy, thus interest rates, thus the national debt.

However, I admit that I, personally, see myself as a monetarist with Austrian sympathies, so I’m not particularly inclined toward the Keynesian view. (Any actual trained economists would see me as “an uneducated ape with too many unearned opinions”—or, in other words, an Austrian.)

This is because of the Cantillion Effect. You can read about it from libertarian right-wingers and anti-monopoly left-wingers, but both sides agree that money-printing inflation hurts ordinary people way more than it hurts banks, financial institutions, and wealthy people. The new money takes time to “trickle down” to consumers in the form of higher wages, and meanwhile the price hikes have already hit.

There may be a niggling question in the back of your head: “James, if printing money causes inflation, why didn’t we see inflation during the 2010s, when the Fed printed more money than ever before in history?” I will answer that in a separate article later this week. I didn’t want to derail this article with several hundred words on quantitative easing and the Case-Shiller home price index. (I’ll update this article with the link when I do.) (UPDATE: here you go.)

The relationship between “current interest rates” and “interest rate on the debt” is complicated, to the point where nobody can actually point directly to it… but it’s a lot more direct than you might expect. Yes, we sell a lot of bonds with 5-, 10-, and 30-year maturities… but a whole lot of our debt is in short-term stuff, highly sensitive to fluctuations in the interest rate. Since 1988, the actual interest we’ve paid on the national debt (interest payment in dollars divided by total debt in dollars) has closely tracked the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury, which in turn has been pretty darned sensitive to increases in the Federal Funds Rate (the baseline interest rate set by the Fed):

Interestingly, the 10-year Treasury seems to be a lot more sensitive to Fed rate hikes (whether actual or anticipated) than to Fed rate cuts.

Table 2-3 of the CBO’s Net Interest Costs primer (December 2020) was the lynchpin of the math. Table 1-1 of that document was also helpful. CBO’s interest rate projections are in Table 2-1 of their “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2021 to 2031” document from February 2021. Table 1-1 of that same document gives us expected revenues and outlays for each year. Smush those tables all together, and you can get a pretty decent pie chart going.

They aren’t. The CBO’s spending projections are charmingly absurd. CBO predicts drastically smaller deficits than we’ve had during the entire past decade (including the financially good years), despite obvious economic headwinds. This is because the CBO is required by law to pretend that Congress’s silly budget tricks and loopholes aren’t fake. In reality, the red wedge on those charts, representing our overspending, is likely to be two or three times larger than in these charts… and the green wedge, representing our debt, will get even bigger even faster as a result. But it’s beyond the scope of this article, and probably beyond the scope of my math skills, to fix all that.

So what do you think will happen to the average person once this all breaks down? I know you half-jokingly said buy gold, but for real, are we just all sort of doomed to suffer?

“Time’s arrow will see to that, if nothing else.” 😂😂