How I Would Have Ruled on Affirmative Action

Right for the wrong reasons for the right reasons, kind of

JUSTICE HEANEY, concurring in the judgment,

In Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard, respondents Harvard and the University of North Carolina defend their college admissions programs, which discriminate on the basis of race. My brethren today find that these programs violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In a concurring opinion, my brother1 Justice Gorsuch finds, furthermore, that these programs violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Gorsuch’s concurrence is compelling. I join his opinion in full.

However, Justice Gorsuch also joins the majority opinion regarding the Equal Protection Clause. I cannot do so. I write separately to explain why not.

I. An Easy Case

A.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act says, “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Applicants to Harvard and UNC are systematically and intentionally denied admission to Harvard and UNC on the ground of race.

Everyone knows this. The majority opinion and concurrences recount some of the most embarrassing details, but there’s no factual dispute that students are accepted or denied because of their race. Harvard admits this on the first page of the very first filing with this Court: “Consideration of race benefits only highly-qualified applicants.” (To more clearly see the admission, delete “only” from that sentence.) The dissents to today’s decision don’t dispute this. That is, after all, the whole point of affirmative action. These programs “make space” for racial-minority applicants by handicapping other applicants who are competing for the same limited slots.

Title VI could not be clearer: this is illegal. Congress said so. Case closed.

So what are we doing here?

B.

Because this case has such a simple answer, this Court need not reach the deep and murky constitutional question about what exactly the Equal Protection Clause prohibits or does not prohibit. If some future Congress changes Title VI to allow discriminatory affirmative action programs, then this Court may need to consider whether those programs comport with the original meaning of the Equal Protection Clause. In the meantime, however, this Court has, for centuries, insisted that cases must be decided on the narrowest dispositive grounds, and especially that this Court avoid ruling on constitutional questions if it possibly can.

That is for the best. Our Equal Protection Clause precedents over the past hundred and sixty years have not clarified these waters. Rather, we have muddied them. As an originalist-textualist, I find it telling that the majority opinion, though laden with many of those precedents, never offers an argument about what the Equal Protection Clause meant to the people who wrote and ratified it.2

Likewise, because this case has such a simple answer, this Court has neither the need nor the right to inquire into broad questions of racial justice, though both dissents try. The question of whether affirmative action is, all things considered, a good policy or a bad one is fraught on both moral and practical grounds. It is well beyond the competence of this Court to decide. Fortunately, “all legislative Powers” granted under our Constitution are given to the People’s representatives in Congress, not to unelected philosopher-kings on this Court, and Congress decided the matter for us in Title VI. For better or for worse, race-conscious admissions are illegal.

C.

There is no way to get around this without doing violence to the text of Title VI. My brother Gorsuch explained this in his concurrence, but, since this is a blog post and not actually a judicial opinion, I won’t assume you’ve read Gorsuch’s concurrence. Here’s a quick recap:

Title VI’s language “on ground of” means “because of.” It does not mean “only because of.” It does not even mean “primarily because of.” This is easily illustrated. Imagine an employer fires a Black man from his job at a shoe-sales firm:

EMPLOYER: We need to cut the budget. I’m sorry, but I’m letting you go.

SALESMAN: Why are you firing me?

EMPLOYER: Because of your bad sales numbers. You sell fewer shoes than 98% of my employees.

SALESMAN: What about Bob? Bob sells the same number of shoes as I do, he’s been here the same amount of time, and he’s exactly the same as I am on every measurable characteristic.

EMPLOYER: Well, we only need to fire one person to make the budget work. Bob is White. You are Black. I like White people better than Black people, so that’s a “plus” factor for Bob.

This employer is going lose his shirt in the lawsuit. You know it, I know it, and that’s the law. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act says, “It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer to… discharge any individual… because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

It is no defense for the employer to say that he fired his salesman mainly for bad sales numbers. The fact that race played any role in his decision-making process makes him liable for racial discrimination under Title VII.

Our precedents describe a simple and convincing rule of thumb: the “but-for causation” rule. If an individual loses his job (under Title VII) or is denied college admission (under Title VI), but she would have been fine but for her race, then that’s unlawful discrimination. For example, if our salesman had been White, he would not have lost his job. That means he would have kept his job but for his Blackness.3

It seems strange to explain this to the dissenters so soon after our decisions in Bostock v. Clayton County and Harris Funeral Homes v. EEOC (2020). I agreed with both decisions. So did my sisters Justices Kagan and Sotomayor, who joined Justice Gorsuch’s majority opinion in both cases.

In Bostock, Gerald Bostock, a man, admitted in his workplace that he was sexually attracted to (and impliedly engaged in sexual activity with) men, and was soon thereafter fired for “conduct unbecoming” a county employee. We held that, if Bostock had been a woman sexually attracted to men (instead of a man sexually attracted to men), he would not have been fired. He would have kept his job but for his sex. Therefore, Title VII was violated.

In Harris Funeral Homes, Aimee Stephens was a male who worked at Harris Funeral Home. Stephens was fired when Stephens announced an intention to “live and work full-time as a woman,” including by violating a company dress code that forbade males from wearing dresses. We held that, if Stephens had been a woman wearing a dress instead of a man wearing a dress, Stephens would not have been fired. Stephens would have kept the job but for Stephens’ sex. Therefore, Title VII was violated.

In order to reach the conclusion that Title VI permits any form of racial discrimination, we would have to argue that either:

the phrases “on the ground of” and “because of,” within the same statute, in neighboring sections, referring to the same sort of conduct, passed at the same time, which the public and the legislature treated as having the same meaning, somehow mean two very different things, or;

the meaning of “on the ground of” is much more flexible than we have previously concluded, and Bostock was wrongly decided (as were many other heretofore uncontested cases in that line). If this is so, then we should reverse Bostock with all haste, and my sisters Justice Kagan and Justice Sotomayor should explain why they no longer think Bostock is correct, or;

this Court pretends “on the ground of” and “because of” mean different things because of some funky lawyer nonsense involving stare decisis.

Can you guess which is the reason we’re here?

II. The Bakke Bear Trap

Although Title VI provides a clear, correct, and final answer to the questions raised by this case, neither the majority opinion nor the dissents even discuss Title VI, much less rely on it. There is a simple reason for this: precedent.

Specifically: bad precedent.

A.

This Court first considered the intersection of Title VI and race-based admissions in the 1978 case The Regents v. Bakke.4

The question in Bakke was the same as the question we face today—or, at least, the question I think we should be facing: “Does Title VI mean what it says?”

Four justices said, “Yes, Title VI means what it says. Race-based discrimination in college admissions has been outlawed by Congress. The end.” This opinion is notable for being, to the best of my knowledge, the only excellent opinion Justice John Paul Stevens ever penned.5 Alas, it was in dissent.

Four other justices said that Title VI doesn’t actually forbid all racial discrimination. They said that Title VI only forbids racial discrimination that is already prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment. In making this claim, the four ignored the text of Title VI, because Title VI’s text quite plainly forbids all racial discrimination. Instead, the four selected certain choice snippets of Congressional speeches and committee reports from the debates over the Civil Rights Act, and construed those snippets to mean that, whatever Congress said in the actual law, its intention was only to forbid some racial discrimination. (Why, on this account, Congress felt the need to pass legislation accomplishing what the Constitution had already accomplished, I am not entirely certain.)

This was called “legislative history” analysis. This method has been almost totally discredited in subsequent decades. Not one justice on today’s Court reads statutes this way. Even if we did, we would be embarrassed by how selectively the Bakke Four cherry-picked their argument. In those days, at its worst, the Court used legislative history to not just rewrite but actually reverse the plain meaning of a statute Congress had passed. Bakke was that worst.

Having ransacked Title VI, the Bakke Four went on to make an argument that the Equal Protection Clause allows race-based discrimination, as long as it is against Whites, not Blacks.6

However, four votes does not a majority make. Bakke was decided by the ninth vote, Justice Lewis Powell. Powell agreed with the legislative historians that Title VI does not mean what it says, and instead prohibits only racial discrimination which is already banned by the Equal Protection Clause. On the other hand, Powell thought the Equal Protection Clause does prohibit all race-based discrimination, even against Whites. He believed there could be rare and special exceptions to this—including in college admissions—but only under certain circumstances. That made five votes for upholding some race-based affirmative action in college admissions.7

Powell’s one-man, split-the-baby, not-entirely-coherent, and definitely incorrect opinion thus became the binding precedent that controlled college admissions rules for the next fifty years. Title VI was judicially rewritten to say something like, “No person in the United States shall be denied the benefits of any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance in violation of that person’s constitutional right to the equal protection of the laws.”

Every subsequent Supreme Court decision on affirmative action was haunted by this rewrite. Instead of considering simple, understandable rules of thumb based firmly in the statutory text, like the “but-for” rule, the Court (under Bakke) had to turn every Title VI case into a full-blown safari deep into the jungle of Fourteenth Amendment case law, hunting for a fixed and judicially cognizable meaning of “equal protection of the laws.” The Court never found one.

It found two.

B.

Bakke’s “Equal Protection” rule for interpreting Title VI was at cross-purposes from the start.

As I’ve explained, Bakke’s controlling opinion held that Title VI only bans conduct already banned by the Constitution. However, Bakke held that the Constitution does ban race-based discrimination. However, Bakke held that the Constitution permits exceptions. However, Bakke held that the exceptions had to be “precisely tailored” to serve a “compelling government interest”—and no more. (A typical example of a tailored exception to serve a compelling interest is temporarily racially segregating a prison in order to forestall an imminent prison race riot.8) However, Bakke held that “obtaining the educational benefits that flow from an ethnically diverse student body” was just such a compelling interest, which is quite a step down from what usually qualifies as “compelling.” However, Bakke held that the other proffered justifications for affirmative action (such as increasing representation, countering the broad effects of discrimination, and helping underserved communities—in other words, the justifications affirmative action supporters actually believe in), were not compelling interests and could not be used to justify racial discrimination. However, Bakke held that…

…I’ll stop there. Let’s just say the first draft of that paragraph went on through five more “howevers.”

In short, Bakke was a decision in profound tension with… itself. Anyone could find whatever they wanted to find in Bakke, and, naturally, they did. There is quite enough material in Bakke to justify an affirmative action system that is restricted in theory but unlimited in fact. (Colleges recognized this and acted accordingly.) On the other hand, there is quite enough material in Bakke to justify a system where affirmative action is permitted in theory, but impossible in fact. The contradictions inherent in Bakke have evaded resolution for an impressively long time.9 The Court’s “swing justices” have managed to present the two faces of Bakke as an actual single rule only by wrapping it in several pounds of duct tape and woo.

That’s the problem with the Chief Justice’s majority opinion and with Justice Sotomayor’s lead dissent: both their interpretations of the Equal Protection Clause are rooted in Bakke, and, since Bakke doesn’t actually make sense, neither of them is altogether wrong!

Fortunately, there is no need for us to extract a consistent meaning from Bakke about the Equal Protection Clause. If we overturn just one small portion of Bakke—the part that erroneously rewrites Title VI to mean something other than what it says—leaving the remainder intact, then we can reach the correct resolution of this case without ever venturing into this jungle.

III. Weighing Stare Decisis

A.

This Court does not normally overturn even a small part of a precedent simply for being incorrect. We normally ask for some special justification before considering whether to overturn a precedent.

Special justifications might include further developments in related law that undermined the original decision. For example, the free speech case Brandenburg v. Ohio overruled Katz v. United States because related First Amendment cases had rendered Katz an outlier. Other times, factual developments undermined the very premises of the original decision, like in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, where the Great Depression so undermined the factual underpinnings of Lochner v. New York that Parrish overturned it.

Sometimes, our “special justification” is that the original decision has proved “unworkable,” spawning divided and ambiguous follow-up decisions, like when Grady v. Corbin added a weird wrinkle to double jeopardy jurisprudence that the lower courts had a hard time applying. This often happens if the original decision is incoherent, stems from a fractured Court, or causes repeated division within this Court. (We reversed Grady in United States v. Dixon, calling it “unstable in application.”)

Occasionally, our “special justification” is simply that the original decision is not simply wrong, but egregiously wrong. When this Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that Plessy v. Ferguson was wrong, we engaged in precious little naval-gazing about stare decisis principles. We saw how wrong Plessy was, we recognized that continuing to apply it would perpetuate a misreading of the Constitution that harmed the plaintiffs, and we overruled it because justice (as well as the law of this country) demanded it.

On the other hand, some factors can weigh in favor of retaining a precedent. When this Court interprets a statute passed by Congress (like Title VI) rather than a constitutional provision (like the Equal Protection Clause), we recognize that, if Congress disagreed with our interpretation, it could simply pass a new statute to overrule us. If it does not do so, then we interpret that as Congress agreeing with (or at least acquiescing to) our interpretation, which lends our precedent greater force.

Moreover, if many people have made important and irrevocable decisions based on our precedent, and would be harmed by a reversal, we call this “reliance,” and we take extra care to avoid overturning a precedent on which there is widespread reliance—even if we have come to believe that the precedent is wrong. For example, in Kimble v. Marvel Entertainment, we stood by a weak precedent called Brulotte v. Thys, which held that a patent license could not demand royalties beyond the expiration of the patent itself, in part because reversing it would cause chaos in the world of patent licenses. Had we reversed Brulotte, many people would have been suddenly and unexpectedly owed royalties on long-expired contracts, which is fundamentally unfair.

B.

Bakke is unworkable. As described above, the original decision was a divisive, incoherent mess from a deeply fractured court, and subsequent decisions like Grutter and Fisher II have only deepened the mess, generating more ambiguities and more fractured courts. In desperate need of resolution between its contrary holdings, Bakke is unstable in application because it is unstable at its heart.

Bakke is also badly undermined by developments in related law. At the time Bakke was handed down, it was not yet established that the phrase “on the ground of race or sex” in the Civil Rights Act was subject to the “but-for” discrimination rule confirmed most recently by Bostock. There ain’t room in the Civil Rights Act for both Bostock and Bakke. Since Bostock was correct and Bakke was not, we should favor Bostock and overrule the narrow portion of Bakke that misconstrues Title VI.

For whatever it’s worth, Bakke’s misinterpretation of Title VI is also egregiously wrong. It doesn’t combine a legal abomination with a moral one, like Plessy v. Ferguson did, but it’s still the worst legal analysis you’ll read in the U.S. Reports10 this year, chock full of not just legislative history, but bad legislative history. It isn’t a close question. If Bakke had never happened, and this Court faced the question of interpreting Title VI de novo today, I’m confident that our decision in favor of the but-for reading would be unanimous—and that any lawyer who tried to make the kinds of arguments Justice Powell accepted in Bakke would be laughed out of the District of Columbia.

There are no reliance interests at stake here. Nobody is directly harmed by a forward-looking change in college admissions policies the way someone is harmed by a monetary contract suddenly shaking you down for money decades after you thought it expired.11

Meanwhile, the canon of constitutional avoidance tells strongly in favor of our taking an off-ramp from the fraught constitutional question in this case. If the bad precedent of Bakke is blocking our off-ramp, it would be an act of judicial responsibility for us to simply remove it, rather than resign ourselves to hurtling full-speed into the jungle of Equal Protection jurisprudence.

C.

Both the majority and the dissents today argue that we cannot overturn Bakke’s misconstruction of Title VI, because (as the majority puts it), “No party asks us to reconsider it.”

I’m not sure what Questions Presented the rest of my brethren think we accepted, but, the QP I saw included:

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act bans race-based admissions that, if done by a public university, would violate the Equal Protection Clause. (Gratz v. Bollinger) Is Harvard violating Title VI by penalizing Asian-American applicants, engaging in racial balancing, overemphasizing race, and rejecting workable race-neutral alternatives?

…and:

Should this Court overrule Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003) [which relied entirely on Bakke -JJH], and hold that institutions of higher education cannot use race as a factor in admissions?

…and, in Harvard’s reply brief:

Whether the Court should overrule Regents of University of California v. Bakke, Grutter v. Bollinger, and Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, and interpret Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to prohibit a private university from considering race as one factor among many in admissions.

Dunno, looks like the Question of how Bakke (and its progeny) treated Title VI was in fact Presented to me!

Second, as my brother Gorsuch contends in his concurrence (footnote 2), we cannot abrogate the plain text of a statute while we are trying to apply it even if both parties stipulate to a misreading of it. We’re the Supreme Court! Text is our business!

Third, if my brothers and sisters still don’t feel that this issue has been adequately briefed and argue, fine! Let’s order a re-hearing to further consider issues that have arisen during our deliberations, as we did in McGirt v. Oklahoma and Citizens United v. FEC!

D.

I don’t think any of the above is the real reason we are leaving Bakke intact. I think this is the reason:

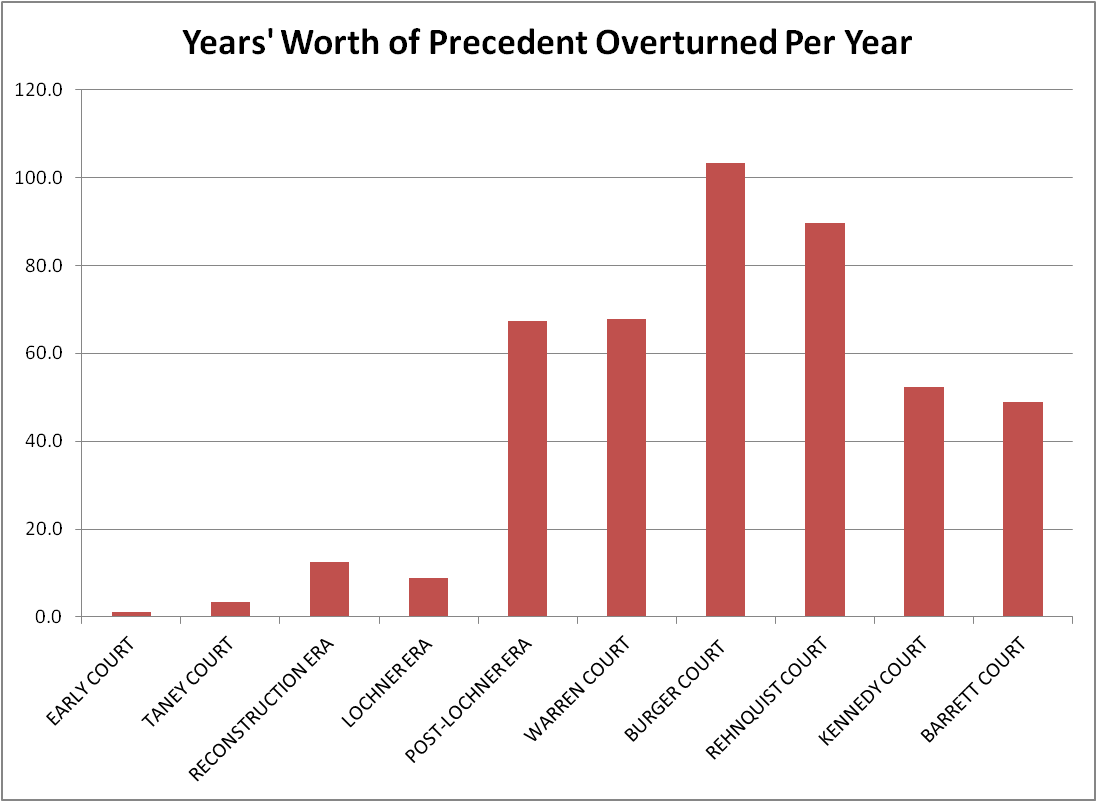

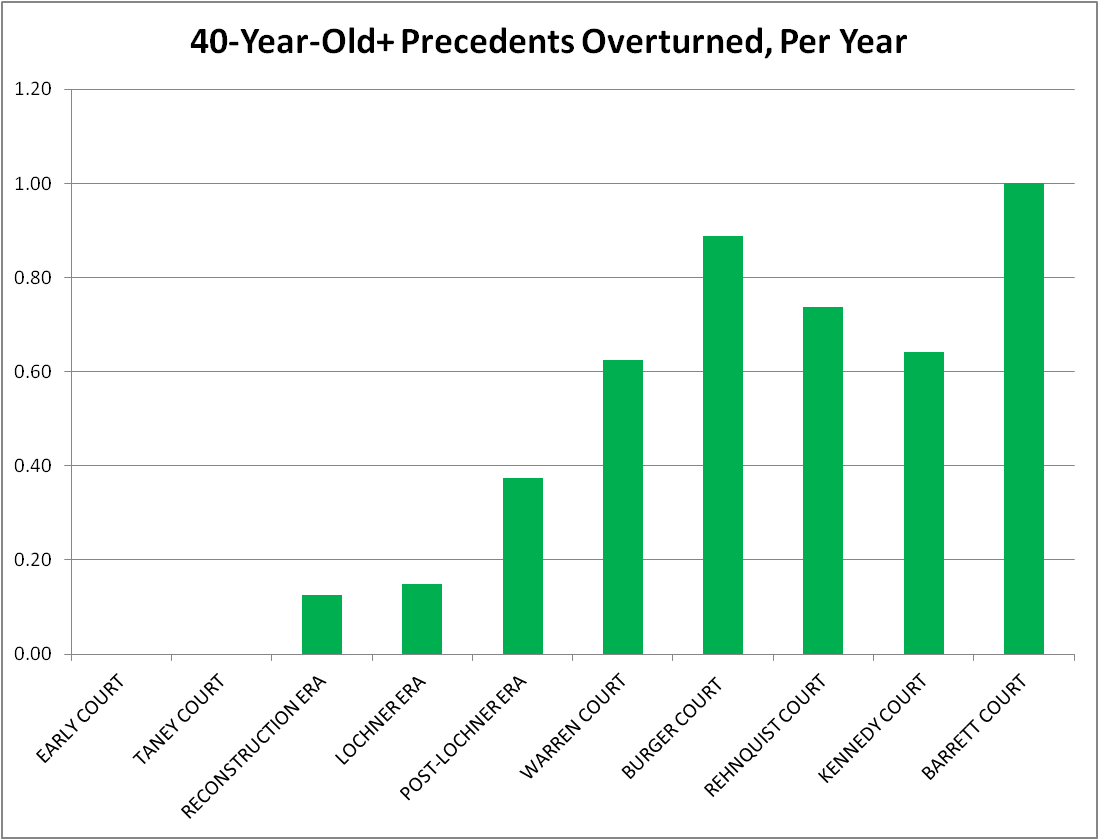

I published those two charts last year, in an article called “The Most Dangerous Time to be a Supreme Court Precedent.”

If the Court today had actually overturned Bakke, even just one small part of it, it would have counted as overturning a 47-year-old precedent. This would have caused much wailing and gnashing of teeth. News stories would have run about how this “conservative Court” is “openly setting aside the rule of law” by “running roughshod through precedents” at a “record-setting pace.” These complaints might even be, in a very technical sense, correct. Feed a few dozen articles by Nina Totenberg, Linda Greenhouse, and Joan Biskupic into ChatGPT, give it the prompt, and you can write the story yourself.

Instead, because the Court carefully avoided overturning any precedents this term (including Bakke), the charts today look like this:

By the metrics, the Barrett Court, in its second full term, is becoming the very model of judicial modesty. I think the desire to avoid explicitly overruling Bakke is the best way to explain the majority’s strange behavior in this decision.

After all, we reached the correct result: Harvard and UNC’s racist admissions programs are illegal. However, by lashing ourselves to the mast of an overripe precedent, we reached that result on a weaker argument, settled questions we had no business settling, left ourselves open to critiques we had no need to entertain in the first place, and issued a constitutional ruling in a statutory case, all while leaving the Civil Rights Act—one of the most important statutes of the twentieth century—permanently maimed. (The majority also had to write a forty-page opinion, whereas my brother Gorsuch solves the case in barely half that.)

But hey, we avoided a bad headline!

Perhaps the majority truly believes statutory stare decisis is such an inexorable command that it justifies this strange approach. I choose to believe better of my brethren. I instead believe that we have allowed ourselves to be a tiny bit cowed by the Nina Totenbergs of the world—not enough to push us into a wrong decision, as in years past, but enough to get us to take the wrong path to the right decision. I have more to say about the undue influence Nina Totenberg’s gang wields (even today) at the Court… but I will say it later, under separate cover.

For today, because the Court correctly rules that Harvard and UNC’s admissions programs rely on unlawful racial discrimination, but incorrectly grounds this ruling in the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause (not the plain text of Title VI), I am pleased to respectfully concur.

Supreme Court justices used to refer to one another as “brothers” all the time in their opinions, sort of like Members of Parliament referring to one another as “my right honorable friend.” This was awesome, and I am bringing it back.

That said, my brother Justice THOMAS, writing alone, makes a good run at an originalist account of the Equal Protection Clause in his inspiring concurrence. I cannot join it—indeed, have not fully read it—because I do not think the question he answers is one that we can reach in today’s case. Because the case can be settled entirely by Title VI, it must be settled entirely by Title VI.

In reality, an employer who wants to commit racial discrimination is probably smart enough to come up with some thin excuse, like “Bob is the boss’s friend’s brother’s former roommate,” or “Bob is on a self-improvement plan that we’re optimistic about,” or “Bob’s sales numbers are down because of that surgery last year, but we think they’re about to rebound.” Without very strong evidence, the employer is likely to get away with this, as long as he doesn’t honestly admit that he’s firing Bob because he’s Black.

This underlines my point: everyone knows the employer will lie, because admitting the truth would be an admission of lawbreaking! Harvard and UNC deserve credit, at least, for admitting to it, which makes our job today very simple.

As the majority opinion observes, the judiciary, after today, will have to trust-but-verify college admissions officials suspected of covertly racist admissions policies precisely as closely as it already trusts-but-verifies the honesty of shoe-sale executives suspected of covertly racist hiring policies.

Everyone else calls this case Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, for the very fair reason that that’s how the case is captioned, but I think that putting “the” in front adds a lot of flair.

Justice Stevens was a good friend of my maternal extended family—a weird story for another day, and, despite never having met the man myself, still the closest I’ve ever been to real power. At one point in the early 1990s, my father (the in-law) got in quite a lot of trouble with the fam because he published an article observing that Stevens’ opinions in Thornburgh v. ACOG and Webster v. Reproductive Health Services were, to use a technical legalism, dogshit.

(My dad never cusses, so he instead expressed this idea in sentences like, “[Stevens’] opinion is so riddled with errors that it requires a careful look.”)

They did not put it so bluntly. Justice Thurgood Marshall’s opinion says:

It is because of a legacy of unequal treatment that we now must permit the institutions of this society to give consideration to race in making decisions about who will hold the positions of influence, affluence, and prestige in America. For far too long, the doors to those positions have been shut to Negroes. If we are ever to become a fully integrated society, one in which the color of a person's skin will not determine the opportunities available to him or her, we must be willing to take steps to open those doors. I do not believe that anyone can truly look into America's past and still find that a remedy for the effects of that past is impermissible.

…but this is just talking around the same thing.

As you can see from that (very typical) paragraph, most legal analysis at the time of Bakke was exclusively about relations between Whites and Blacks, because, at the time, 98.6% of Americans were either White or Black. We really have become a strikingly more diverse country in the subsequent fifty years.

That’s one reason this lawsuit is so flummoxing to existing precedents: Harvard today is getting sued by Asians, who simply weren’t part of the analysis in 1978! It turns out Asians don’t fit easily into the narrative of racial kyriarchy perpetuated by institutions like Harvard, and, as a result, Harvard finds itself in the awkward position of discriminating against a minority.

This sounds messy, but it was actually much messier. The five justices in the “majority” of the badly fractured court spawned seven separate written opinions. Since stare decisis draws its strength in part from the coherence of the precedent, it is important to note that Bakke lacked this coherence.

A permanent policy of racial segregation in prison failed this test, in Johnson v. California (2005). Even if your racial segregation is to prevent violence, even if you’re segregating prisoners (who have reduced constitutional rights), the Supreme Court says that still isn’t compelling enough to justify racial discrimination unless violence is imminent. “Compelling interest” is a very high bar.

In 2003, the Court heard Gratz v. Bollinger and Grutter v. Bollinger, two cases about affirmative action programs at two Michigan universities. Given its inherent instability, Bakke seemed doomed. Bakke would probably not be officially overturned, but Bakke’s internal contradictions needed to be resolved. If the progressives resolved them, we would end up with a rewritten Bakke that (in effect) allowed affirmative action across the board. If the conservatives resolved them, we would end up with a rewritten Bakke that (in effect) forbade all racial discrimination.

Instead, Bakke was saved. Once again, the Court in Gratz and Grutter split 4-4, with one tiebreaking judge Once again, the deciding judge “split the baby”: Justice Sandra Day O’Connor ruled against racial discrimination in Gratz but for it in Grutter. (The school in Gratz was insufficiently holistic about its use of race.) My sister O’Connor’s major contribution to the Bakke canon was to add even more instability, by creating an ambiguous “durational requirement”:

We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today. (Grutter v. Bollinger, O’Connor’s majority, end of Part III, page 343)

However, she didn’t make the twenty-five year limit part of the holding. However, she did insist, as part of the holding, that some “durational limit” was necessary to make a race-conscious admissions process constitutional. However, she was ambiguous about whether an actual sunset date was necessary, or whether “periodic reviews” (which, in practice, always find racial preferences are still needed) would suffice. She was also not clear what these periodic reviews could possibly be reviewing, since Bakke forbade quotas and other race-based metrics to review! As a result, just as today’s majority and dissents each embrace plausible readings of Bakke, they each today embrace plausible readings of Grutter. (Although I concede that the majority’s reading is significantly better.)

Finally, in 2016, in Fisher v. University of Texas (aka “Fisher II”) the Court did the same dance again, this time with Justice Anthony Kennedy playing the role of tie-breaker, deciding vote, and Bakke-protector.

Fisher II held that, in pursuing “diversity writ large,” universities could only use race-conscious methods if the university’s goals were “measurable,” not “elusory or amorphous.” Fisher II then turned around and also held that obviously not measurable goals like “the destruction of stereotypes” were, in fact, measurable, without indicating how that could possibly be true. Today’s majority focuses on Fisher II’s requirement that the goals be measurable; the dissent simply asks whether the goals are substantially similar to those blessed by Fisher II. By looking at different elements of Fisher II, they reach contrary conclusions. Again, contradiction built on contradiction, tension on tension.

Bakke was a dog’s breakfast, and our subsequent precedents just poured maple syrup over it.

The book where Supreme Court decisions are published annually.

I realize Justice Sotomayor, in her dissent, articulates a far broader and vaguer notion of “reliance.” According to her, reliance is “generated” whenever our decisions lead to “settled expectations” among some subset of Americans, not just when reversal would cause direct and unavoidable harm. (This reliance analysis was strangely absent from the opinion she joined in Obergefell v. Hodges, which overturned the “settled expectations” promulgated by Baker v. Nelson, several dozen longstanding state laws, and centuries of universal practice.) She also suggests that universities have invested a lot of sunk costs in the current DEI framework—but past sunk costs are not the same thing as sudden and unavoidable new costs of the sort that generate true reliance.

It seems to me that the version of “reliance” Sotomayor embraces is not founded in our precedents, but rather in the aphorism, “Stare decisis is an old Latin phrase that means ‘Let the wrong decisions of the Warren Court stand.’”

(Yes, Bakke was technically the Burger Court.)

On FIRE lately!! Keep the hits coming

I have to agree with you that if the Supreme Court was going to overturn prior decisions on affirmative action, it should have done so through the plain text of Title VI, instead of the 14th Amendment as filtered through the specifics of a fractured Court's precedent.

As Justice Jackson argues, equal protection is not identical to non-discrimination or color blindness. Guaranteeing a group equal protection can mean passing laws specifically protecting that group from ways that they are targeted that others are not. It can also mean taking action to right injustices that have effects of unequal protection or result from prior unequal protection.

But that's harder to argue with the language of non-discrimination that Congress passed in the Civil Rights Act. You could make a case that "non-discrimination" in this case carries a public meaning derived from the 14th Amendment, so that righting injustices is within its scope rather than what you might guess with no context. Since I haven't read Bakke, maybe that's what it does and you're being ungenerous. But even if so, the 14th Amendment says equal protection, and Title VI says non-discrimination, and affirmative action is easier to square with the former than the latter.

If the Court ruled narrowly based on the law before them, as you suggest and as they should, then Congress could in theory revise the Civil Rights Act with language that enables affirmative action. By making a ruling based on the Constitution, the Court tells Congress that even if they could muster the votes, the law wouldn't last. It won't be worth the political cost, so don't try. Since you probably oppose affirmative action, maybe this changes your mind that the Court acted rightly and shrewdly!

Should the Court also ban legacy admissions, which have clear racial bias, in accordance with Title VI? In your view, could it have done so within this same decision, by including them as an at least partially race-based admissions practice?