Explaining Your West Saint Paul (Dakota County) Property Tax Statement

OR: Why Did My Taxes Go Up While My Neighbor's Went Down? What the Heck Kinda Deal is That?

Every year, we in West Saint Paul, Minnesota get our property tax notices in the mail. Every year, people ask the same questions in the West St. Paul Neighbors Facebook hellscape group. What the heck is going on with my property taxes? Is the city council robbing us blind? Or am I just house-wealthy and paying for it?

These questions are very reasonable! Property tax is weird.

It's easy to understand a sales tax: I spent $100 dollars at Kohl's Target, so I must pay an extra $7.60 to Mr. Government ($6.90 to Minnesota, $0.50 to West Saint Paul, and $0.20 to Dakota County).

It's easy to understand an income tax: I made X dollars this year, so I must pay Y% of those dollars to Mr. Government. Figuring out X and Y takes a lot of math and reading IRS documents, which is why most people have tax preparers do it for them, but we all get the gist of an income tax.

Property taxes are harder. I don't use a tax preparer for my income taxes, I normally do them by hand, so I'm pretty good at reading tax documents for a total layman... but even I find the property tax process weird and confusing. The city website features this earnest but devastatingly uncanny movie, but it's not very specific. It took me years to work out this simple understanding of the process, and I'm still not certain it's 100% correct. (If you see an error, please let me know!)

Property Tax is Actually a Bunch of Different Taxes Smushed Together

Here's my property tax notice for 2022: https://gis.co.dakota.mn.us/content/tnt/42-01800-82-130.pdf

Don't worry, I didn't just post my private information online! In fact, property tax information (including the name of each property owner) is public information. You can look up the property tax info and deed owner for literally any address in West Saint Paul using Dakota County's wonderful GIS tool, and pretty much everyone's address is public through either TruePeopleSearch.com or TheRealYellowPages.com or (for a nominal fee) WhitePages.com. (The county auditor also has a public voter file with addresses, but I think you have to drive to get it.) This is a fun way to spend an evening if you're as lame as me.

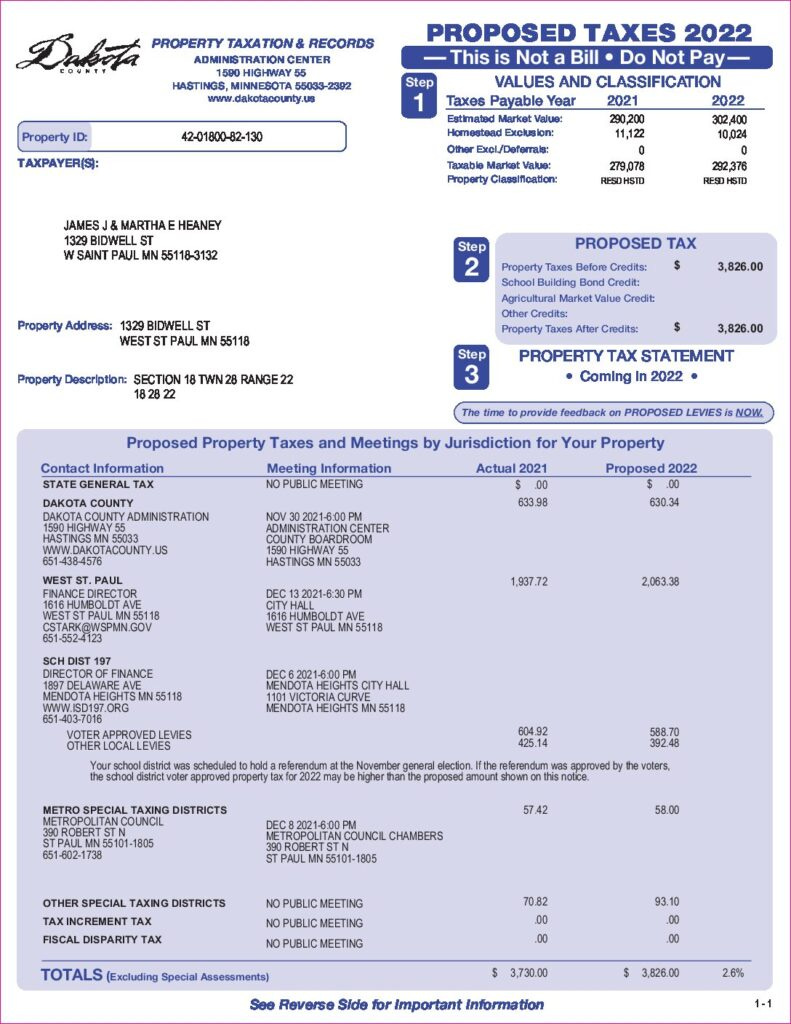

I looked through about a dozen property tax notices picked at random from around WSP, but mine's pretty typical, so let's walk through it. Dakota County officially believes I will owe a total of $3,826 in property tax next year. However, that number is actually a bunch of different taxes added together into one number. As you can see, I'm actually getting my property taxed by:

Dakota County ($630)

The City of West Saint Paul ($2,063)

Minnesota Independent School District #197 (Mendota-Eagan) ($981)

The Met Council ($58)

"Other Special Taxing Districts" ($93), which is maddeningly vague but seems to be (based on this):

Metropolitan Mosquito Control District (since 1958!)

Many Dakota County residents also pay into a watershed district, usually the Vermillion, but, as far as I can tell, no one in West Saint Paul is in a watershed.

All these different groups are taxing your property, all of them separate from each other. For simplicity, Dakota County collects all* these separate taxes in one big check—but, when your property tax suddenly goes way up, this makes it difficult to tell exactly who's responsible. Did the schools get more expensive? The light rail line? Did South Metro EMS need a new ambulance? To figure this out, you have to go item by item.

How These Numbers Get Picked

The biggest line item by far is the tax for the City of West Saint Paul. This is also the line item that increased the most from 2021 to 2022. This is true not just for me, but for everyone whose property tax statement I looked at. West Saint Paul is the big ticket item.

So let's take a look at how the City of West Saint Paul decided that I owe them $2063 this coming year.

The Levy Amount

Some people say that you should start figuring property tax by looking at your home value. This is wrong and backwards. The city neither knows nor cares what your property is worth when it makes the crucial decision: how much money is the city going to spend this year?

That decision was made in two city council meetings: on August 9th, 2021 (pp5-53), the city's staff proposed a budget. On September 13th, 2021 (pp71-80), the city council voted to approve it. (Thank you to the West St. Paul Reader recaps for making this info much easier to dig up.)

The details of the West Saint Paul budget are fascinating, but that will have to be a separate blog post. The bottom line is: in 2021, the city had a budget of $45.9 million. Property taxes paid for $17.8 million of that. (The rest of the money came from other sources.)

In 2022, the city cut the budget to $39.0 million, reducing its total expenses. But West Saint Paul's revenues are also falling, so it needs property taxes to cover more of the total. So, in 2022, West Saint Paul has decided that it needs $18.7 million in property taxes. (A 4.7% increase from last year.)

That's the magic number: $18.7 million. The city has to raise that amount of money from the properties within the city. Ultimately, your personal city tax is based on that number.

But, first, there's some math.

Property Valuation

In theory, the City could just say, "Okay, we need $18.7 million and we have 9,174 individual residential properties. Let's share it evenly! Every property owner in the city must pay $2027!" This is essentially a head tax.

But this would be rejected by everyone as outrageously unfair. It would mean someone living in a tiny $170,000 house on Annapolis would be paying the exact same property tax as someone in a $486,000 mansion on Mainzer—and they'd both be paying the same tax as a landlord sitting on a property worth $22 million. The vast majority of us share an intuitive sense that this would not be fair: wealthier people should pay a greater share of the taxes. So we designed our property taxes to function as wealth taxes instead of head taxes.

Wealth taxes are tough, because wealth is hard to measure. What's a house really worth? You can't know until you sell it on a free and open market. This is a big problem for all sorts of wealth taxes. How do you decide how much Jeff Bezos is really worth? So much of his money is tied up in expensive art or investments in other companies or unique real estate or rocket ships—none of which has a universally agreed-upon monetary value. Indeed, this sort of problem has led other countries to abandon wealth taxes.

But America has refined the art of taxing property wealth to a near-science. Here in West Saint Paul, assessors from Dakota County drive around every year and use a bunch of rubrics to make a very educated guess at what each and every property in the area is worth. This educated guess is not final. If you think they're wrong, you can phone them up and ask them to do a more detailed assessment; if you think they're still wrong (and you can prove it), you can even take them to court.

Dakota County thinks my house is worth $302,400. I don't really think my house would sell for that much, but it's close enough, and I don't really have the evidence to fight it, so I accepted this figure when they informed me of it last year. So $302,400 is my Estimated Market Value in the upper-right corner of my tax statement.

MN <3 Homesteaders

I live in my own home. Minnesota law likes people who live in their own home (aka "homesteaders"). In a variety of ways, Minnesota massively favors homesteaders, penalizing landlords (although landlords pass many of their extra costs on to renters, who are then screwed). On property taxes specifically, Minnesota gives two big legs up to homesteaders: the Homestead Exclusion and the Homestead Refund. The Homestead Refund (Form M1PR) is a (large) tax rebate you get for being a low- or middle-class homesteader; look it up next time you do your taxes, but I won't go into it here.

The Homestead Exclusion is just a straight-up property tax deduction. It takes your Estimated Market Value and cuts it down. The smaller your house, the bigger the deduction, because the government does not want to drive poor people out of their houses. (Also, homeowners vote!) If you have a house worth $191,000, your Homestead Exclusion for 2022 is $20,050, so Dakota County has to tax you as if your house is only worth $170,950. My house is worth $302,400, so my exclusion is only ~$10,000, and Dakota County taxes me as if my house were worth $292,400. (The exact formula is set by state law.) Once your home is worth more than $413,800, the Homestead Exclusion phases out completely—the state assumes that if you live in a house that big, you can afford to pay full property taxes on it.

The bottom line is, in the eyes of Dakota County, my house is worth $292,376. That's my Taxable Market Value.

City Staff Does Some Algebra

After doing all this hard work for every single property in Dakota County, the County informs West Saint Paul of the taxable value of each and every one of them.

Add it all up and you get a number, the total amount of property value in West Saint Paul. Let's call it $2.65 billion. (It's not $2.65 billion, because I've completely ignored a ton of property types, like commercial and apartment properties, which are taxed at higher rates... but $2.65 billion is a useful example number.)

So the city has $2.65 billion of property laying around, and needs to raise $18.7 million. What tax rate do they need to impose in order to get that $18.7 million? Easy! That's seventh-grade math:

total property value * tax rate = desired revenue

Or:

$2,650,000,000 * [tax rate] = $18,700,000

Or:

[tax rate] = $18,700,000 / $2,650,000,000

= 0.7057%

(Again, this gets more complicated when you include the other property classes, which are taxed more than homesteads, but the basic algebra is the same, and that tax rate is correct.)

The residential homestead property tax rate for West Saint Paul for 2022 is 0.7057%. That's how much the city has to tax each household in order to get the money it needs for next year. The tax rate is flat, so the wealthy pay more and the poor pay less, but it takes an equal slice of everyone's wealth. (At least, assuming all wealthy people live in big houses and all poor people live in small ones.) Officially, this tax is neither progressive (which would mean hitting rich people harder, like the income tax) nor regressive (which would mean hitting poor people harder, like the sales tax).

My house's taxable value is $292,376.

$292376 x 0.7057% = $2063

...and, sure enough, $2063 is exactly how much I owe the city in this year's taxes. That's my bit of the $18.7 million.

Don't Be Fooled

Sometimes, people who want to make some kind of political point about property taxes (pro or con) will try and argue that taxes really went down (in some clever nine-dimensional chess sense) when actually they went up (or vice versa).

For example, as we've seen, the West Saint Paul tax levy in 2022 grew 4.7%, from $17.7 million to $18.7 million. So, collectively, our taxes went up 4.7%.

However, the tax rate in 2022 only grew from 0.6966% to 0.7057%. That's only a 1.3% increase. Some people try to argue that this means your taxes only went up by 1.3%. That's not accurate. In reality, the city asked for quite a bit more money, but we had more "money" to give them already, so they didn't need to raise the rates by as much to get what they wanted. (I put "money" in scare quotes because, of course, we don't actually have the money our houses theoretically "created" this year. We don't see a dime of that cash unless we sell our houses, and I, for one, intend to die in this house some time in the 2070's, by which time I expect my house to be worth much less due to age and national population decline.)

Others will argue that your taxes didn't really go up because the city demanded more money; they went up because your home gained value. Again, that's not generally accurate. Your home's value only determines your share of the taxes, not the amount. The levy size determines the amount. There are rare cases where a home's value goes way up (or down) in value, much more than other houses in the neighborhood. If your home value does something crazy during the year, you may end up paying a bigger (or smaller) share of the $18.7 million than you did in the past, because the city now thinks you are significantly richer (or poorer) than you used to be. For most of us, though, with relatively average home value increases, we're paying (more or less) the same share of the tax as before, but our taxes went up because the tax is just plain bigger.

(EDIT 17 November: Basically, if your city tax increase is exactly 4.7%, then that's entirely because of the levy and not at all because of changes in your home's value. If your city tax increase is 5.1% or 4.3%, you're still very close, and the overwhelming majority of that increase is due to the city levy increase. The further away your city tax increase is from 4.7%, the more your home value appreciation is responsible. If your city taxes went up 9.8% this year, half of that is the city tax and half of it is because your home value went up considerably faster than the city average.)

So don't be fooled: if you want to know whether the city raised or lowered taxes, the number you should be looking at is the size of the levy itself ($18.7 million), not the residential tax rate, not the value of your home, not the total value of all homes in the area.

(If you want to be really accurate and fancy about whether taxes are going up, the number you should truly look at is the size of the levy per resident. But our city's population changes quite slowly, and census numbers usually lag by a couple years. Still, this can make a big difference! Using 2020 census numbers for both 2021 and 2022, I find a levy-per-resident of $864 in 2021 and $905 in 2022... which works out to a 4.7% increase, exactly the same as if you look at the actual levy increase. But if we assume that our population went up by 100 residents in 2022, the new levy-per-resident is only $900, an increase of only 4.2%. It'd be cool if the city figured out a way to identify and publish this number.)

I should note that the West Saint Paul city government, to its credit, does not make these arguments. Some people in the city have done so (I won't point fingers), but the city itself always prominently publishes the levy number and its percentage increase; the city never tries to hide the ball by talking about absolute rates instead. Moreover, West Saint Paul's 4.7% levy increase for 2022 is actually the smallest levy increase since 2014. (See p64 of this document, ignoring the 2022 projection, which turned out to be a little off.) Our taxes are still going up significantly, but less than they have in recent years.

On the other hand, the city expects the 2023 levy to go up by 5.62%, which is closer to the ten-year average increase—and the size of the levy has clearly outstripped inflation, sometimes drastically, on average. (Inflation was well under 2% for nearly the entire 2010s; our property tax levy increases were held to that only once, barely, in 2012, under Mayor John Zanmiller.)

This Is Pretty Much How They All Work

Each of the government units listed on your property tax form goes through basically this exact same process. First, the County/School District/Council decides how much money they need next year. Then, they each add up the total amount of property value in their designated area. Then, they set a tax rate that ensures they get the money they've decided on. They apply that rate to the Taxable Market Value of your property, multiply, and, boom, that's what you owe that government unit for the year.

Of course, every government unit on the list covers a different geographic area, so they all have different property values to work with. The Metropolitan Mosquito Control District covers the entire seven-county metro area, with millions of taxpaying residents, so they need only a very small amount of money per property to make their (already relatively small) budget work. On the other hand, Dakota County has a lot of property... but a lot of it is rural, so the average value of that property is relatively low compared to, say, ISD 197. This variation means every levy has to be calculated separately, with different property rates for each one.

A Couple of ISD 197-Specific Notes

ISD 197 has several different property tax levies, some of which are voter-approved and others which aren't. These are all broken out into two line items on our property tax statements: "voter approved levies," which we voted on at some point, and "other local levies," which is just code for, "This is what ISD 197 is taxing you without your direct say-so." I have not been able to locate a web page or report where ISD 197 transparently breaks down what each of these levies is, what each one costs, where they come from, and when they expire... but my Internet has been wonky tonight, so it could very well be out there and I just can't find it.

First, I want to commend ISD 197 for a useful thing it does: while it doesn't tell us the size of the levies per resident, it tells us the size of its levies per student (and does the same for individual levies). This is arguably the most useful way of tracking at a glance whether the district is increasing its spending because of increasing needs or if it's just getting bloated.

Interestingly, the district collected $1,073 per pupil in 2021, but, if this West St. Paul Reader report is accurate about the total district budget, then the district spent $14,965 per pupil in 2021. This really shows that all the sturm und drang about the $224-per-pupil levy referendum was pretty small potatoes in the grand scheme of things; the vast majority of ISD 197's budget does not come from property tax. (Most of it is from state income tax.)

Second, speaking of that $224-per-pupil levy we all voted on last November... it passed! This does not technically raise our taxes, because this was merely a renewal of a levy that was already in place (albeit at a slightly higher level, because the levy is adjusted annually for inflation).

However, when Dakota County put together these tax proposal sheets, it did not know whether the levy was going to pass or not. So they followed current law and assumed that the levy would fail. Therefore, our ISD 197 line item on this tax statement doesn't include the levy. Now that the levy has been approved, the actual tax bills we receive next year will be adjusted to account for the continuation of the levy.

Bottom line: the average ISD 197 resident's actual ISD 197 tax will be about $52 higher than what it says on this form. Mine will be $49 higher. You can compute your share here (enter your home's Taxable Market Value into the box). So instead of paying $588.70 like my tax statement says, I actually expect to pay $637.70 in the coming year. (Probably slightly higher, but I'm too lazy to figure out the inflation component tonight.)

Property Taxation is a Terrible System

As far as I can tell, Dakota County in general (and each government within it) does a really good job administering the property tax system. Every county in Minnesota has a property tax, and every state in the Union has at least one jurisdiction that charges a property tax, too. As these things go, I have no complaints about how Dakota County, specifically, does it. In fact, I've had two interactions with Dakota County assessors since I moved here, and both of those interactions were excellent.

But it's a pretty rotten system, when you get to thinking about it:

Property tax administration requires a vast national army of assessors to guess at the value of each and every property in the land. They do their best, but their guesses may or may not be accurate. Home value isn't like income, where we know how valuable the income was because the number is literally printed on the paycheck. Instead, to tax home value, we have to employ essentially a separate detective force just to find out what exactly we're taxing. This is expensive and inefficient. Politicians in Washington frequently remind us of the vast logistical difficulties and guesswork involved in wealth taxes... so why don't we apply that same logic to the one wealth tax that just about every American, from the richest to the poorest, has to pay? (If you're a renter, sorry, you're paying property tax, too: your landlord just adds it to your rent. You get the tax without the homesteader benefits.)

The complexity of this system makes it non-transparent. That makes it difficult for voters to hold their elected officials accountable. Instead of being taxed a percentage of a concrete number you know really well and have a lot of control over (like your salary, or total household income), you are instead taxed based on a funny little number that jumps up or down based on impersonal market forces you neither control nor fully understand. Because of this wild movement, your absolute tax rates jump up or down, too—often without a clear or close relationship to the overall size of the levy! Many voters end up not understanding who they are paying taxes to, how much the taxes are, whether they're going up or down for everyone or just them, or how any of it gets decided. Others have to read (or write) 4,500-word blog posts to get a handle on it.

We end up speaking in broad generics, like, "Hoo boy, West St. Paul taxes are getting pretty high, aren't they? But at least we don't live in Regular Saint Paul! They'd tax you double what we pay!" But this completely misses the fact that, actually, West Saint Paul city taxes are nearly twice as high as Saint Paul's tax ($905/resident in WSP vs. $566/resident in SP). It's just that our county taxes here in Dakota County are so low (less than half of Ramsey County's) that it somewhat cancels out (and hides) how much West Saint Paul is actually charging us. This confusion, in my opinion, is largely due to the property tax system's confusing structure. Despite everything Dakota County and West Saint Paul do to make that structure transparent to us, it's just very hard to keep straight.

The property tax structure is not just confusing and obscure; it's fundamentally dangerous. Taxes are generally taken from transactions: when you spend money or make money, you pay the taxman a small portion of it. You can factor those taxes into your planning before you spend or earn. When you buy a candy bar, you know to mentally add 7% or so to the sticker price. If you win the Powerball Jackpot, you know you're only going to get about half the sticker price after the government gets its cut. And we have a whole bunch of safeguards in the rest of our tax system to ensure that, if you earn extra money, your taxes go up a little, but not more than the extra amount you actually earned. That way, you know you always have the money to actually pay the taxes.

But when you buy a house, how much are you going to owe in property taxes over the life of the property? Answer: who the hell knows? Literally no one. Might go up, might go down, might go way up. This isn't just bad for financial planning; it can put the most marginalized members of our society on a knife's edge.

Suppose you earn minimum wage, and you've spent your whole life scraping together a little nest egg to buy a small $50,000 house to call your own. You pay $210 in property taxes per year, and can just barely scrape that plus home maintenance costs together. And you are happy. But then there's a housing frenzy in your area. It's the Hot New Place To Live. HGTV comes to town and starts flipping houses left and right. Over the course of three years, your houses rises in value to $120,000, just because everyone wants to live in your cool neighborhood now. Now your property taxes are (this is true) $654/year. You can't afford that!

You live on minimum wage. That wage hasn't gone up. You don't have any extra money coming in. You haven't done anything to the house. It certainly hasn't printed you extra money. Yet your taxes have more than tripled.

You can't get blood from a stone, so you have no choice but to sell your house and move. But where? The whole neighborhood has gone up in price. You can't stay here. You'll have to find another neighborhood to live in. But how can you get to your job from a whole different neighborhood? Now you're either paying for transit in both money and time, or you're looking for a new job. You had a social support network in your neighborhood, but everyone else you know just crashed into the same problem, and they're being scattered to the four winds.

And that's how property taxes displace impoverished and minority communities, in a process we all know as "gentrification." We spend all this time as a culture worrying about the community-shattering effects of gentrification (and how it reinforces racial segregation between neighborhoods), but never seem to notice that our state and local governments have direct and absolute control over one of the primary mechanisms driving it. (Between property tax and zoning codes ugh, it seems to be cities, more than any other entity, that drive ongoing segregation.)

Gentrification is even worse on renters. At least homeowners, when they are forced to sell, do generally get some of the benefit of home value appreciation, and they get to choose when and how they sell. When landlords sell, they pocket the profits and evict the residents, often with little warning.

In fact, the whole structure of property taxes is a bum deal for renters. Remember when we said that the property tax is officially flat? In reality, it's not: it's regressive. Renters (who are disproportionately poorer) inevitably end up paying the landlord's property taxes (who else would?) and eat a large share of any property tax increase (although the exact tax incidence is hotly debated among economists). So renters are paying property tax, but indirectly, without the ability to challenge the valuation of their homes, without enjoying the benefits of the Homestead Exclusion, with far far smaller Homestead Refunds (seriously, the difference is stark)... and, usually, apartments are charged property tax at a higher rate than single-family homes to begin with.

Tax us when we sell our houses, heck tax the dickens out of it—that's income!—but don't tax us just for living in one. Housing is a basic necessity of life, and the only thing most of us do in a given year to earn this inefficient, regressive tax is keep breathing.

The state of Minnesota already has a state income tax... which means we already know the incomes of everyone in the state. Income taxes are easy to design as progressive taxes (our state's is particularly progressive), everyone basically understands them, and people will always be able to afford them. Many other states already have local income taxes. I believe we should abandon property tax and fund our towns, schools, and mosquito control agencies through local income-tax-based levies instead.

Of course, it'll never happen. The system is too big, too interconnected, too universal, and too complicated to transition to a new tax collection method, especially in an era of polarization, bureaucracy, and impotence. There are probably difficulties with local income tax that I haven't foreseen. (Tell me about 'em in the comments!) But I couldn't write a whole blog post about property taxes without at least mentioning the deep structural problems with it.

I hope this post leaves you with a better understanding of your West Saint Paul property tax statement!

*FOOTNOTE:

There are two other items on your tax statement that are almost certainly "$0.00". Quickly, they are:

Tax Increment Tax. This applies only in (some) business districts, and is a complicated way of subsidizing private developers. I don't think it applies to any WSP residences; if it does, it's very few.

Fiscal Disparity Tax. This tax applies only to commercial/industrial lots. It's a way for Dakota County to redistribute wealth from rich towns to poor towns (which makes some sense).

UPDATE 19 November: The West St. Paul Reader just tackled property taxes as well, and (wisely) spoke to the lady in charge!

Interestingly, the city acknowledged an error in its numbers. The budget reported a levy increase of 4.74%, a figure I used throughout this article. The actual figure appears to be 5.15%. I am not updating the article body, because I think inline updates would be more confusing than clarifying, but it's worth noting anyway that all my "4.7%" figures should be "5.2%" instead. I have not (yet) double-checked the city's other reported finance figures.