The Minnesota Disqualification Suit continues. There have been some very interesting filings made since the case began, and the parties have said lots of very interesting things, but I’m not quite ready for a Daily Disqualification upDate post. We have one more central issue to sort.

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

—U.S. Constitution, Amendment XIV, Section 3, the “Disqualification Clause” (emphasis mine)

Last time, I decided to examine the question of Donald Trump’s disqualification by starting with the important stuff and working down to the minutiae (unlike a court of law, which goes the opposite direction). I started with the most important question of all: is it even legitimate to consider declaring a candidate disqualified? Should you ever take that decision away from the voters themselves? I answered yes, if the law includes qualifications, because we live in a republic, not a democracy.

Today, I proceed to the crux of the issue: has Donald Trump “engaged in insurrection or rebellion against” the Constitution of the United States, or “given aid and comfort to the enemies thereof”?

If Trump did not do either of those things, then we’re done here. If Trump is not an insurrectionist in the first place, none of the other legal questions about “officers” or “self-execution” matter: he’s qualified to be president again. The other stuff is still interesting (to me) but academic.

On the other hand, if Trump did do either of those things, then there’s a very strong case that Trump not only is disqualified, but that he deserves to be, indeed that the framers intended him to be, and that voters who continue to support him thereby injure the Constitution itself. Everything hinges, then, on three questions:

What did the key words of the Disqualification Clause (“engage” and “insurrection” and all the rest) actually mean to the ratifying public when the framers put them into the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868?

What, exactly, did President Trump do on January 6, and what was his intention when he did it?

How do the first two answers fit together?

What’s an Insurrection?

Last week, Mr. Trump’s lawyers,1 for the first time, opined (p18) on what an insurrection is. This allows us to see what common ground there is between Trump, who denies he engaged in insurrection, and legal scholars like Paulsen & Baude, who argue that he did engage in insurrection.

Trump agrees with Baude-Paulsen (citing an 1868 law dictionary) that “taking up arms traitorously against the government” constitutes both rebellion and insurrection.

Trump further agrees, citing an 1863 lower-court decision called U.S. v. Greathouse,2 that violating the Treason Clause by “levying war” against the United States constitutes insurrection.3

Since Trump cites Greathouse’s notion of “levying war” as constitutive of insurrection, it seems to necessarily follow that Trump accepts and affirms Greathouse’s own analysis of who is guilty of “levying war”:

War being levied, all who aid in its prosecution, whether by open hostilities in the field, or by performing any part in the furtherance of the common object, ‘however minute or however remote from the scene of action,’ are equally guilty of treason within the constitutional provision. In treason there are no accessories; all who engage in the rebellion at any stage of its existence, or who designedly give to it any species of aid and comfort, in whatever part of the country they may be, stand on the same platform; they are all principals in the commission of the crime; they are all levying war against the United States.

“In treason, there are no accessories.” That sounds broad. Is the Greathouse court saying that even people who never fire a shot or even pick up a weapon can still insurrectionists?

Yes—and then some:

In Ex parte Bollman and Ex parte Swartwout, Mr. Chief Justice Marshall, in delivering the opinion of the supreme court of the United States, said: ‘It is not the intention of the court to say that no individual can be guilty of this crime who has not appeared in arms against his country. On the contrary, if war be actually levied—that is, if a body of men be actually assembled for the purpose of effecting by force a treasonable purpose—all those who perform any part, however minute, or however remote from the scene of action, and who are actually leagued in the general conspiracy, are to be considered as traitors.’ And in commenting upon this language, on the trial of Burr, the same distinguished judge said: ‘According to the opinion, it is not enough to be leagued in the conspiracy, and that war be levied, but it is also necessary to perform a part; that part is the act of levying war. That part, it is true, may be minute; it may not be the actual appearance in arms, and it may be remote from the scene of action, that is, from the place where the army is assembled; but it must be a part, and that part must be performed by a person who is leagued in the conspiracy. This part, however minute or remote, constitutes the overt act, of which alone the person who performs it can be convicted.’

So, according to the key authority cited by the Trump campaign, “if a body of men be actually assembled for the purpose of effecting by force a treasonable purpose,” then “all those who perform any part, however minute, or remote from the scene of action, and who are actually leagued in the general conspiracy” have engaged in an insurrection.

Quite frankly, this is much more than I expected the Trump campaign to concede in an initial filing. All told, the position they adopt with respect to Greathouse isn’t all that far off from the Paulsen-Baude position.

I suspect that Team Trump finds itself in a bind. They want to give “insurrection” as narrow a meaning as possible, in order to separate President Trump’s actions on January 6 from the definition of “insurrection.” So they dig up Greathouse, which seems to confine “insurrection” within the boundaries of the “levying war” language of the notoriously demanding Treason Clause.

However, Greathouse makes “insurrection” a synonym of “levying war,” not by reading “insurrection” narrowly, but by reading “levying war” broadly. In Greathouse, “levying war” means not just picking up a gun in order to suspend the execution of the laws, but simply “performing any part, however minute, or however remote from the scene of action,” so long as one is “actually leagued” in the attempt to suspend the laws. This interpretation of the Treason Clause is so broad that it seems to swallow the entire Disqualification Clause up within it—simply because everything you can plausibly imagine to be disqualifying also counts as treason!

The other judge in Greathouse (Judge Ogden Hoffman, Jr.) said as much, explaining how the “aid and comfort” part of the Disqualification Clause is coextensive with their broad reading of “levying war”:

It is perhaps not easy, by a general definition, to describe all the acts which would amount, in judgment of law, to a giving of aid and comfort to an enemy. The text writers, as we have seen, describe it on general terms as including all such acts as would, if given to a rebel within the realm, amount to ‘a levying of war.’ What constitutes a levying of war has already been considered; but in the point of view in which I am now treating the question, it is necessary to examine what acts have been held to be ‘a giving of aid and comfort’ to a public enemy, and to see whether the acts committed by the defendants in respect of this rebellion are of the same nature.

Among the cases mentioned by the writers of ‘an adhering to the enemy, giving him aid and comfort,’ are the following: Raising men in England with intent to dethrone the king, and sending them abroad to the enemy (the French). Taking treasonable papers in a boat to go on board a vessel bound to France, where they were to be used for treasonable purposes; and, indeed, every species of treasonable correspondence with the enemy, although the intelligence may not have reached him. And, in general, the mere sending of money, provisions or intelligence to the enemy, is giving him aid and comfort, though on the way they should happen to be intercepted, and never reach him. So, too, it has been held that cruising on the king's subjects under a French commission, France being then at war with England, is an adhering to the king's enemies, though no other act of hostility was laid or proved. It was not denied at the bar that a similar act, under a letter of marque issued by the authorities of the so-called Confederate States, would constitute both a levying or war and an ‘engaging in the rebellion, giving it aid and comfort.’

Greathouse goes on to observe that no formal declaration of war is necessary for a jury to conclude that an insurrection has occurred or is occurring:

The existence of the rebellion is a matter of public notoriety, and, like matters of general and public concern to the whole country, may be taken notice of by judges and juries without that particular proof which is required of the other matters charged. The public notoriety, the proclamations of the president, and the acts of Congress are sufficient proof…

The defendants in Greathouse were rebel sympathizers who had outfitted a boat with enough weapons to engage in piracy and, meanwhile, obtained letters of marque from Confederate “President” Jeff Davis “authorizing” them to go plunder some Union shipping. The defendants were apprehended by the U.S. Navy mere minutes after pulling away from the wharf, never having fired a single shot for the Rebellion. They didn’t even get the sails up before the Navy boarded and seized their schooner. Nevertheless, all were convicted of “engaging in rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States.”4

Remember, this is all from the case cited by Donald Trump! This is common ground! I haven’t even opened the Baude-Paulsen paper yet!

Trump’s filing makes a few further contentions:

Trump argues that the “aid and comfort to the enemies” part of the Disqualification Clause refers only to “enemies” who represent de jure or de facto foreign governments, like France, the elected government of Georgia, or the so-called “Confederate government.” Trump maintains that weakly-organized mobs (like the January 6 attackers) are not a government, even de facto. Therefore, such mobs cannot trigger the “aid and comfort” portion of the Disqualification Clause. Given that Greathouse defines “levying war” in cases of rebellion so broadly that it covers everything the “aid and comfort” clause could conceivably cover, I’m not sure how much of a practical difference this makes, but Trump has well-paid lawyers and lawyers are very careful to dot their i’s like this.

Based on two disqualification cases5 tried in Congress in 1870, Trump argues that you can’t be disqualified for speeches made before a rebellion actually exists. Even if you give a speech saying, “Yes, North Carolina should stop any Northern invaders and defend Southern honor,” you’re scot-free as long as you give that speech before North Carolina actually rebels.

It is worth saying a little about these two cases. Trump uses these cases to stand for the proposition that speech acts before an insurrection cannot themselves be insurrection. However, there are are a few salient points Trump’s analysis omits:

In both cases, the questionable speech was not personal speech. Both candidates had been sitting state legislators in the weeks leading up to the Civil War. Congress questioned them mainly6 not over speech, but over votes they had taken that increased funding for state militias (which had not yet seceded) and called for an avoidance of war (albeit sometimes in very belligerent terms).

In both cases, the questionable “speech” took place weeks or, more usually, months before the start of the Civil War. For example, one of the accused (Rice) voted for a resolution that vowed to “resist such invasion of the soil of the South at all hazards, and to the last extremity”… but he did so three months before Sumter, before the federal government had even formally determined that secession was illegal.7 The “speech” thus could not be construed as a cause of the insurrection. By contrast, when P.G.T. Beauregard, on April 11, ordered his men to open fire on Fort Sumter later that night, that speech act was so closely connected to the first shots of the insurrection (at 4:30 a.m. on April 12) that Beauregard was certainly an insurrectionist when he gave the order—even though his speech was technically “before” the war started, and even though he never fired a weapon on Sumter himself.

One of the two accused (McKenzie) was known to all as a staunch Union man, in word and deed. In fact, he attempted to get elected to Congress from his home district several times during the War, even holding an election while half his district was occupied by the Confederate Army! (Congress denied the validity of most of his elections, but he still served in Congress for a couple of months in 1863.) While the House made clear that personal loyalty wouldn’t have exonerated him had he committed unambiguously disloyal acts, his loyalty also meant the House didn’t interpret his more ambiguous actions through a lens of disloyalty.

Everyone agreed that, after Fort Sumter was attacked, if either candidate had taken further votes funding the rebels, given speeches belligerently supporting the rebellion, or even just voted for pro-rebel legislative resolutions, they would have been disqualified.

Indeed, in 1867, the Senate excluded Senator-elect Philip Thomas under a law (the Ironclad Oath) that prefigured Section 3 in many respects. Baude & Paulsen explain:

What had Thomas done to support the South in its rebellion? Apparently, he had permitted his minor son, a member of his household, to join the Confederate army, and given his son $100 on the way out the door. The Senate debated whether Thomas had done anything more by way of counsel or encouragement of his son’s taking up arms against the United States and it is not clear how the senators evaluated such evidence. Some seemed to have thought Thomas’s treatment of his son disqualifying. Others focused instead on allegations that Thomas had resigned as President Buchanan’s Treasury Secretary because he disagreed with the President’s decision to send federal reinforcements to Charleston Harbor. Either theory of Thomas’s exclusion… include[s] conduct of a… passive… nature—allowing one’s son to become a rebel soldier, under circumstances where such permission (and financial assistance) might have been withheld; [OR] opposing, or resisting, measures to suppress insurrection and defend national institutions and personnel…

In none of this do I disagree with a jot or tittle of what Trump’s legal team has proposed about the meaning of insurrection. I am only adding a little bit more context, which might become relevant later on.

This is all very interesting, but a bit abstract. Let’s take Trump’s theory of insurrection for a quick test-drive on familiar recent events.

The George Floyd Insurrections?

I know the media had a meeting one night8 and decided to call the nationwide race riots “unrest” for some arcane left-wing language-policing reason. However, on the face of them, some of the race riots during Summer 2020 bore a more-than-passing semblance to the January 6 attacks, which the media universally called an “insurrection.” Indeed, far more people died in the race riots than in the January 6 attack.

So were they an insurrection? Under Trump’s framework, recall, insurrection is to levy war against the United States, and war is levied whenever “a body of men be actually assembled for the purpose of effecting by force a treasonable purpose.”

First, let’s consider the violent rioting that devastated certain corridors of my hometowns, Saint Paul and Minneapolis. These were extensive, expensive, and were certainly carried out by a body of men actually assembled for an evil purpose... but their purpose was not treason. They were not levying war against the State; they were assaulting private businesses, often to loot them. Sure, they hit the occasional DMV, but only incidentally. To my knowledge, no court has ever held that violent assemblies for a private purpose can effect treason. To quote the well-reputed Case of Fries (C.C.D.Pa, 1800), “…assembling bodies of men, armed… for purposes only of a private nature, is not treason, although… great outrages [are] committed to the persons and property of our citizens… When the intention is universal or general, as to effect some object of a general public nature, it will be treason, and cannot be considered or construed or reduced to a riot.” The Floyd riots, for the most part, were just looting and rage, without any objective of a “general public nature,” and were therefore only riots.

Second, we may consider the burning of the Minneapolis Third Police Precinct. This is a closer call. It seems to be that the arson had a treasonable purpose—forcible opposition to the rule of law in the Third Precinct. The attackers could then get on with their Purge-like activities. (Remember that innocent shopowner they roasted to death, and then the Biden Justice Department gave a sweetheart deal to the man who lit the match? No wonder J6’ers feel hard done by.)

However, the Minneapolis police precinct was part of the state government. If that attack was an insurrection, it was an insurrection against the state of Minnesota, not the United States, which means it may be an “insurrection” within the meaning of the Militia Clause, but seems to be excluded from the Disqualification Clause (which only bars insurrection against the Constitution of the United States, not the State of Minnesota). Minnesota has no state-level Disqualification Clause in its state constitution, so the insurrection against the Third Precinct has no legal effect on the insurrectionists’ eligibility to hold office.

Third, take the siege of the federal courthouse in Portland by “antifa” forces, which featured repeated assaults on the building, “mortar fireworks,” attempted arsons, and much more, in a nightly battle that dragged on for months. This was carried out by organized anti-government forces whose direct goal was to impede the enforcement of federal law and the justice of its courts within Oregon. It seems clear to me that they were assembled against the United States for a treasonable purpose which they aimed to effectuate by force. This was an insurrection, at least under the Trump definition of “insurrection.” In fact, I don’t know how you could possibly define January 6 as an insurrection without including the courthouse siege as an insurrection. Surely, if the Whiskey Rebellion was an insurrection, so was the Portland courthouse siege. True, the attacks were useless and there was no question that the feds would win in the end. However, turning again to the Case of Fries, we read, “…it is altogether immaterial whether the force used is sufficient to effectuate the object; any force connected with the [treasonable] intention will constitute the crime of levying war.” Anyone who participated in the siege during that entire multi-month period, who had previously taken an oath of office to uphold the Constitution, is therefore disqualified from holding further office.

Moreover, anyone who “played a part” in facilitating the attack, “no matter how minute or remote,” including merely communicating useful information or encouragement to the attackers, or even (in some cases) passive cooperation with them, falls within the meaning of “insurrection,” even on the narrower Trump-Greathouse definition. I don’t know enough about the details of the Portland siege to know whether any candidates for public office were drawn into this, but it would not surprise me in the least to find that some city alderman somewhere in Oregon donated to a GoFundMe for one of the insurrectionist groups while the insurrection was going on, or that he was on a text chain with one of them and cheered her on. That’d be engaging in insurrection.

Finally, let’s take a look at CHAZ, the “Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone” that briefly declared independence from Seattle and the United States in June 2020. This was clearly secessionist behavior, and was by no means legal. Clearly, it could have been a precursor to rebellion, just as it was in the antebellum South. There was significant private violence within the zone (which is what eventually led police to clear it). However, when the law moved in, it met with no meaningful resistance. Some of the individuals who violently resisted arrest might conceivably be charged with attempted insurrection, but it’s a stretch, and CHAZ overwhelmingly acquiesced. It was a protest that got out of hand, but, since it never turned violence against the state, it was not an insurrection within the Trump-Greathouse definition.9

Since incidents of actual insurrection during the Floyd protests seem very few and far between, it seems safe to say that the vast majority of protestors did not commit disqualifying insurrection. The great majority were peaceful, far distant from the sites of insurrectionary violence, and neither aided nor advocated for the violence.

Of course, it must be said that, whatever the ultimate verdict on Trump and those who engaged in violence in his name, the overwhelming majority of people who visited Washington in support of President Trump on January 6 were peaceful, too. Like the Floyd protesters, they do not deserve to be publicly shamed or (in some cases) to lose their livelihoods for mere presence at a rally where they peacefully expressed sincere (if misguided) views about the election.

A Change of Plans

My plan was to start this article with Trump’s view of insurrection, contrast it with the Baude-Paulsen10 view of insurrection (plus insights from other scholars), and then explain where I think each side gets it right (and wrong).

Trump does get some significant things wrong about what “insurrection” meant to the ratifying public in 1868.11 (For that matter, so do Baude-Paulsen.12) However, given Trump’s acquiescence to Greathouse, I’m not sure that it matters all that much.

Naturally, if I were a lawyer prosecuting this case, I would fight the defense for every inch of territory. However, I’m not a lawyer. I’m a blogger, and I think my case is more convincing to you, the reader, if I fight this battle entirely—and a little bit generously—on Trump’s turf. For the remainder of this blog post, I accept Trump’s narrow definition of “insurrection or rebellion.”

Even under Trump’s narrow definition, though, I still think he “engaged in insurrection.” I do not think it’s a close call. He did it. Let’s see if I can convince you he did.

In the next several sections, I frequently cite statements of fact from Growe’s petition. Rather than festooning this article with two hundred footnotes, I mark those inline by paragraph number with the letter G… for example, “(G47),” and you can look up her sources there.

Likewise, I cite statements of fact from the Final Report of the House Select Committee on the January 6 Attacks and its associated sack of evidence. These are marked by page number, for example, “(J694).” The J6 Committee had an anti-Trump skew, but its empirical fact-finding, to my knowledge, is undisputed.

Naturally, at the end, I will also consider the Trump campaign’s response.

I have a clear opinion, strongly argued for. However, I feel that my opinion is based on the facts. I have tried to interpret them fairly, without omitting or distorting anything relevant. If you feel I have cheated here in any way, be assured that my failings are at least honest failings, and let me know in the comments.

Setting the Table: From Election to Insurrection

The story of the insurrection on January 6 necessarily begins months earlier, with the general election on November 3. What happened between November 3 and January 5 was not insurrection (at least, not by the Trump-Greathouse definition), but these events nevertheless “set the table” for the insurrection that eventually occurred.

On November 3, 2020, each state and the District of Columbia held popular elections to seat a total of 538 presidential electors. Electors who had publicly pledged to support Joe Biden won a majority of the seats available that night. Those electors were duly certified by their state governments. On December 14, they cast their electoral votes. 306 voted for Biden—a majority.

From that day on, then-President Trump made frequent public claims that the November 3 preliminary election had been tainted by fraud so widespread that it affirmatively changed the outcome of the election from a Trump victory to a Biden victory. This claim was and is factually false.

This is an insurrection post, not an election post, and I do not have room to analyze both issues at once. However, I know some De Civ readers are very uneasy about the 2020 election results. I have therefore written a companion post entitled “Biden Really Won,” which provides a short summary of all the surprisingly many ways we know that—even though there were some real problems with the 2020 election—Trump still lost.

Most importantly for today: President Trump knew he had lost the election. Indeed, he knew this well in advance of January 6. Far moreso than his supporters (whom he systematically deceived), Trump was affirmatively aware that his stolen election claim was unsupported by sufficient evidence, and indeed contradicted by overwhelming evidence.

Days after the election, former Cambridge Analytica product head Matt Oczkowski, by then Trump’s top data guru, bluntly told Trump that, based on the data, he was going to lose. (G53A) Trump disagreed, contending that he was going to win enough court cases to change the outcome. I don’t condemn him for this: in early November, uncovering fraud and winning the election in court (Bush v. Gore-style) was very unlikely, but it was not crazy talk. Trump could have believed this in good faith.

However, on November 23, Trump-appointed Attorney General Bill Barr, whose Justice Department was at the forefront of investigating every credible claim of fraud or illegality, told the President directly: the claims were “just not panning out” because they were “not meritorious,” and Trump’s biggest bugbear of the time (alleged fraud by Dominion voting machines) had “absolutely zero basis” and was “complete nonsense.” (J375)

Up to that point, “the Kraken” story might generously have been construed as an error in judgment. However, Trump continued to claim the Dominion voting machine story was true (J376), even after his own hand-picked, loyal, expert attorney general had carefully explained how it was false.

On December 1, Barr announced publicly that the Justice Department had “not seen fraud on a scale that could have effected a different outcome to the election.” This enraged Trump, leading to an argument in the Oval Office with Barr. Once again, Trump listed various conspiracies: alleged vote dumps, ballots in suitcases, pre-filled ballots in a truck, and so forth. Barr dismantled each conspiracy using evidence gathered from FBI and Justice Department investigations, including multiple interviews with witnesses. Trump had no rejoinder to all this evidence and began criticizing Barr personally instead.

The next day, Trump continued claiming that these conspiracies were real, although he now knew that they were not13 (J377). Trump had not been presented with additional, superior information from another source. He simply didn’t like the facts Barr gave him, ignored them, and continued making claims Barr had shown him were false. In a courtroom, that’s called a “lie.”

In the meantime, even though Trump’s legal theories were wild and unsupported by evidence, he still had a legal right to vindicate them in a court of law. He tried, but, because his theories were wild and unsupported by the evidence, he lost court case after court case. Contrary to a common lie from Team Trump, many of those cases were not dismissed on technical grounds, but were actually decided on the merits. The evidence frequently dismantled Trump’s claims. He continued to make the now-disproven claims anyway.

On December 27, acting Attorney General Jeff Rosen (a Trump appointee) and acting Deputy Attorney General Richard Donoghue (a Barr appointee) spent two hours on the phone with President Trump, going through a litany of claims before once again explaining “based on actual investigations, interviews, actual reviews of documents, that these allegations simply had no merit.” Donoghue told Trump “flat out” that “much of the information he’s getting is false” (J215). The President was undeterred, insisting that the lack of evidence could only be because Rosen and Donoghue “weren’t doing [their] job” (G67).

Soon after, Trump and a lackey tried to pressure Rosen into signing a letter saying that the Department of Justice had found enough evidence of fraud to justify state certification of “alternate” pro-Trump presidential electors. This letter was based on affirmatively and knowingly false claims, and the certification of “alternates” was plainly both groundless and lawless. When Rosen refused to go along with this, Trump fired him. (He reinstated Rosen only because the White House Counsel and much of the Justice Department threatened to resign in protest.)

Trump also fired BJay Pak, U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Georgia, who was in charge of investigating what had become known as the “State Farm Arena video”. The apparent reason Trump fired Pak? Pak concluded, like the FBI and Georgia investigators had already concluded that everything in the video was above-board. (J389-401) You can see for yourself why he drew that conclusion.

Trump was aware of the evidence demonstrating that there was no fraud in State Farm Arena video, yet Trump continued to insist that the video proved fraud. It is not enough to say that Trump’s continuing claims were groundless; his claims didn’t even make sense. Trump never even attempted to explain the overwhelming evidence that there was no fraud in that video. He just kept insisting there was fraud in that video. How? He never explained. This provides evidence of Trump’s state of mind: it is nearly impossible to characterize his continued claims about State Farm Arena as a good-faith difference of opinion.

In fact, revealing his awareness of his own dishonesty, Trump told Rosen at an earlier meeting, “just say the election was corrupt and leave the rest to me” (J271). This demand for a conclusion (whether or not supported by evidence) further clarifies that Trump, likely aware that his claims were not true, was probably not attempting to identify the true outcome of the election. The demand suggests that, instead, Trump was simply trying to delegitimize the true outcome of the election, in order to prepare the way for his impending attempt to violate the Twelfth Amendment. Trump didn’t ask what the evidence showed. He asked for a declaration.

Even without a declaration from the Justice Department, though, Trump was building support. A large number of Americans, who reasonably trusted that the President of the United States would not simply tell them bald-faced lies that could be materially disproven, came to believe Trump’s stolen election claims during the weeks leading up the January 6. On December 10, he tweeted, “How can you give an election to someone who lost the election by hundreds of thousands of legal votes in each of the swing states[?]” (G89b) Trump was aware that there was no credible evidence of fraud at even a tiny fraction of that scale. On December 15, he tweeted, “Tremendous evidence pouring in on voter fraud!” (G89c) Trump was more aware than any other person in the entire country that there was no such evidence.

In my head, I can hear some of my respected friends saying, “Well, that’s just how Trump talks.” Yes, it is, but that doesn’t change his lies into something else. Lies aren’t illegal, but they are lies. “We all know to take him seriously, but not literally.” Unfortunately, a large portion of the country did not know that, and, because of Trump, millions of voters now literally believe that Joe Biden was elected illegitimately on the backs of “hundreds of thousands” of “fraudulent” votes. Lying, in itself, is not a crime—but, as we shall see, a well-placed lie can play an important role in other crimes.

As it became clear that the courts were not going to give him what he wanted, Trump adopted a fringe legal theory, pressed by law professor John Eastman, according to which Vice-President Pence might use his position as presiding officer of the electoral vote certification on January 6 to unilaterally disregard or contest some of the electoral votes cast for Biden, thereby changing the outcome of the election in Trump's favor. Pence disagreed with this theory, in part because it was insane.14 (To understand why, imagine Trump wins the 2024 election, but Vice President Kamala Harris announces, without evidence, that she thinks there was fraud and simply throws out the Trump electoral votes. That would both violate the Twelfth Amendment and—rightly—provoke a civil war.) Yet that was the theory Trump demanded Pence act upon. Because Pence refused, Trump harangued Pence, both in private and in public, for several weeks leading up to January 6, to try to secure his compliance. (J427-469)

There’s nothing insurrectionary about sincerely adopting a legal theory in good faith—even a patently silly one like the Eastman theory. There’s also nothing insurrectionary about applying hardball pressure tactics to try to get another political actor to adopt your legal theory. Heck, even adopting a crazy legal theory in bad faith isn’t an insurrection. That’s good news for Trump: given that Trump had been repeatedly presented with determinative evidence that he had fairly lost the election, it is difficult to see how one might conclude that his support for the Eastman theory was in good faith.

On December 18, Trump tweeted at Senate Republicans, “We won the Presidential Election, by a lot. FIGHT FOR IT! Don’t let them take it away!” On December 19, Trump tweeted, “Big protest in D.C. on January 6. Be there, will be wild!” (G97) Although belligerent rhetoric is part and parcel of any political conflict, many Trump supporters (as well as many of his opponents) thought these were different. They interpreted these tweets (especially the second one) as a “calling forth” of his supporters for violent action. Some of these supporters began composing detailed plans for concerted, violent resistance to Congress’s lawful certification on January 6. To give a clear example, Kelly Meggs of the Oath Keepers militia responded to the December 19 tweet by messaging a friend:

Trump said It’s gonna be wild!!!!!!! It’s gonna be wild!!!!!!! He wants us to make it WILD that’s what he’s saying. He called us all to the Capitol and wants us to make it wild!!! Sir Yes Sir!!! Gentlemen we are heading to DC pack your shit!! (J515)

Meggs would follow his orders as he understood them. He and many co-conspirators responded to Trump’s tweet by banding together and making detailed plans to attack the Capitol, occupy it, and suspend the Twelfth Amendment of the Constitution. (Meggs is now serving twelve years.)

Anticipating a protracted battle on January 6, the Oath Keepers cached tens of thousands of dollars worth of weapons at sites around D.C.. During the week before January 6, one Oath Keeper, Stewart Rhodes, spent over $22,000 on military-grade weapons, night-vision wear, and similar accessories for one of these caches. (J515) Meanwhile, on January 5, the “Stop the Steal” organization held rallies around D.C., at which speakers told audiences things like, “We are at war,” that “we will not return to our peaceful way of life until this election is made right,” that they were prepared to “fight” and “bleed,” that “1776 is always an option,” that “We must rebel,” that “we might make this Fort Trump” (G115).

Those preparing for insurrection understood the constraints on President Trump’s communications, and considered their context and subtext in a way that President Trump’s lawyers, in their filing, refuse to even acknowledge. One of the soon-to-be insurrectionists wrote in late December that the President “can’t exactly openly tell you to revolt” (because Trump could be then be removed under the Twenty-Fifth Amendment). Thus, the insurrectionist wrote, the will-be-wild tweet was “the closest he’ll ever get.” (J527)

Indeed, if you were a President attempting to call an armed force to Washington without crossing the line that would get you immediately removed from office, what would you have done differently?

The White House was aware of the growing threat of violence. Press Secretary Hope Hicks “suggested… several times” that President Trump publicly remind protesters to remain peaceful. Senior Advisor Eric Herschmann made a similar suggestion. Trump refused. (J65) Before noon on January 6, Trump and his staff were aware that an armed force (composed partially, but by no means exclusively, of unofficial militias like the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys), motivated by Trump’s knowingly dishonest Stolen Election Claim, had entered the District of Columbia to support Trump. Trump and his staff had reasonable, actionable indications from intelligence services and other sources that the armed force intended to use violence against the U.S. Government at Trump's direction, and that it had activated detailed plans to that end. (G122-128, 134)

Indeed, when he arrived at the Ellipse for his January 6 speech, Trump was furious because his security would not allow anyone through security without a weapons check. Thousands of those gathered refused to pass through security, watching the speech from outside the secure zone (which impeded Trump’s desire for a huge crowd picture). Trump knew why they didn’t want to submit to a weapon check. He just didn’t care:

I don’t fucking care that they have weapons! They’re not here to hurt me! Take the fucking mags [magnetometers] away! Let my people in! They can march to the Capitol from here! Let the people in! Take the fucking mags away! (J70)

This quote is open to some interpretation, but does make it sound like President Trump knew that the armed force was loyal to him, and like he knew the targets they were planning to hurt.

At this point, under our definition of an “insurrection,” an insurrection has apparently begun: a “body of men” has “actually assembled for the purpose of effecting,” “by force,” a “treasonable purpose.” They intend to “levy war” against the United States, and their attack is imminent. The question, from this moment forward, becomes whether Trump intentionally “plays any part, however minute” in the insurrection that now exists, and whether he is “leagued in the conspiracy.”

So let’s pause for a moment and consider where things stand at this point, 11:45 a.m. on January 6.

At this point, Trump affirmatively knows that his claims of election fraud are false, that he has lost his election cases, that there is no legal path forward except a cockamamie theory that says the Vice President can unilaterally throw out electoral votes on knowingly false claims of fraud. However, he knows that the Vice President is not going to comply with this theory. Legally, Trump is out of runway, and he knows it.

At this point, the only other option on the table appears to be what his supporters are calling “the 1776 option”: a body of men assembling to suspend the Twelfth Amendment of the Constitution by force (and to compel Pence to execute the Eastman Theory). Although they lack full insight into the detailed plans of the insurrectionists, Trump and his staff do know, at the very least, that the “1776 option” is being widely discussed among his supporters.

At this point, Trump has called to Washington a crowd that includes a coordinated insurrectionist force, loyal to him, that is now actually assembled before him. Did he intend this? A plain-text reading of Trump’s “will be wild” tweet includes at least the suggestion of violence, insofar as a sitting president can suggest violence without getting removed under the Twenty-Fifth Amendment. Certainly, some of Trump’s supporters interpreted the tweet, in context, as a directive (not a suggestion) to engage in violence, and they are about to act on it. Despite knowing that some of his supporters are interpreting his tweet as a call for violence, Trump has repeatedly refused to communicate that they misinterpreted him. The honest judge must at least ask whether Trump has refused to clarify because the insurrectionists didn’t misinterpret him at all.

At this moment, Trump is stepping before a crowd that he knows is at least partially armed, and at least some of whom (he, at the absolute minimum, suspects) intend violence in order to suspend the lawful operation of the Constitution.

Ask yourself, between nobody but yourself and Almighty God: if you saw this story playing out in a Netflix documentary about, say, Myanmar, what would you expect to happen next? What would you infer about the President’s intentions here? (Don’t tell me yet; tell God. The rest of the article will shed more light on these questions.)

The Capitol Insurrection Unfolds

At 11:57 a.m., Trump began to address a crowd of tens of thousands, which he knew included both peaceful protesters and the organized armed forces he had called forth.

During his address, Trump called on his forces (which he referred to as his “movement”) to “confront” this “egregious assault on our democracy” by “demand[ing] that Congress do the right thing and only count the electors who have been lawfully slated.” (Trump's implication that some electors were about to be unlawfully counted was, again, false, and he knew that.) Trump insisted, “You'll never take back our country with weakness. You have to show strength and you have to be strong.” He said, “Republicans are constantly fighting like a boxer with his hands tied behind his back... [W]e're going to have to fight much harder.” What does “fighting much harder” look like, when legal options are exhausted? What did Trump mean by this, if not what the Proud Boys thought he meant by it?

Trump directed his forces to “walk down to the Capitol” to “see whether or not we have great and courageous leaders, or whether or not we have leaders that should be ashamed of themselves throughout history.”

Specifically, Trump falsely insisted to his forces that, if Pence failed to execute the Eastman Theory, Pence would not be would not be "uphold[ing] our Constitution," that Pence would demonstrate a lack of "courage," that Pence would be guilty of "listen[ing] to RINOs and... stupid people," that Pence would not be "do[ing] the right thing," and that Pence's manifold betrayals would cause Trump to unfairly lose the presidential election. Trump made these claims over the express objections of his own senior advisor, Eric Herschmann. (J582)

Trump's 73-minute address to the crowd ran for over ten thousand words. To put that in perspective, you’re not even to the 7,500-word mark in this incredibly long blog post. Just one of Trump’s ten thousand words, at the 16-minute mark, inserted by speechwriter, mentioned an ideal of acting “peacefully.”

Does that word, by itself, uttered once and without conviction, prove that the famously mercurial and contradictory Trump never intended what happened next, that he never even suspected the effect his words would, in fact, have? Or might that single “peacefully” be reasonably interpreted, by an impartial judge, as a thin reed of (im)plausible deniability? Again, I ask you to consider the question privately, between yourself and whatever you call God, before you think about answering me.

Regardless of your answer, many observers who considered Trump’s entire address in full context did in fact believe that Trump was directing his forces to prevent, by violence, Congress’s lawful certification of electoral votes. Here is one of Trump’s armed supporters, who was charged with assaulting an officer with a flagpole, explaining himself:

Huttle: We were not there illegally, we were invited there by the by the President himself… Trump’s backers had been told that the election had been stolen…

Reporter: But do you think he encouraged violence?

Huttle: Well, I sat there, or stood there, with half a million people listening to his speech. And in that speech, both Giuliani and [Trump] said we were going to have to fight like hell to save our country. Now, whether it was a figure of speech or not—it wasn’t taken that way.

Reporter: You didn’t take it as a figure of speech?

Huttle: No. (J73)

I read the same speech. I agree with Huttle. Huttle is neither an idiot nor a rube. In context, his takeaway was one reasonable interpretation of Trump’s speech. In fact, while other valid interpretations exist, I think Huttle’s interpretation is the best interpretation. Huttle’s only mistakes were believing the President of the United States was telling the truth, in good faith, and consequently obeying the President’s directive to “take back our country” with a “show of strength.”

At 12:53 p.m., while Trump was still speaking, lightly-armed elements of his forces in Washington, who believed themselves to be acting as his direction, initiated concerted, violent resistance to the electoral vote certification by overrunning the barricades at the U.S. Capitol, attacking U.S. Capitol Police sent to respond, and entering restricted grounds. This occurred at the Peace Circle, which lies on the shortest-line path from the Ellipse (where Trump was addressing his forces) to the U.S. Capitol. (J645)

At almost the same time, the FBI discovered pipe bombs at RNC headquarters and, shortly thereafter, DNC headquarters. The need to deal with the pipe bombs drew substantial Capitol Police resources away from the defense of the Capitol, weakening it at a critical moment. (J706) If that wasn’t actually planned as a distraction, it was a brilliant coincidence for the attackers. Indeed, had the pipe bombs gone off, January 6 could have been much worse. (Vice-President-Elect Kamala Harris was at DNC HQ when the bomb there was found.)

If you had any doubts that there was an insurrection at the time Trump’s speech began, you may now set them aside: a body of men has now not only assembled but actually levied war on the federal government in order to effect the treasonable purpose of suspending the operation of the Twelfth Amendment of the Constitution.

And Trump is still speaking! There are fourteen minutes left in his address to the crowd! At 1:07 p.m., he concludes with the line, “[W]e fight. We fight like hell. And if you don't fight like hell, you're not going to have a country anymore.” By the time he says those words, his loyalists are already fighting like hell—in hand-to-hand combat with Capitol Police!

As we saw above, there are Civil War-era precedents which suggest that people cannot be called insurrectionists for pro-insurrection speech that happens before the insurrection commences violence—not unless the speech is quite closely connected to the firing of the first shot. However, Trump’s lawyers cite these precedents to defend Trump’s January 6 speech. That doesn’t work. First, some of the most incendiary parts of Trump’s speech took place after the violence had started!15

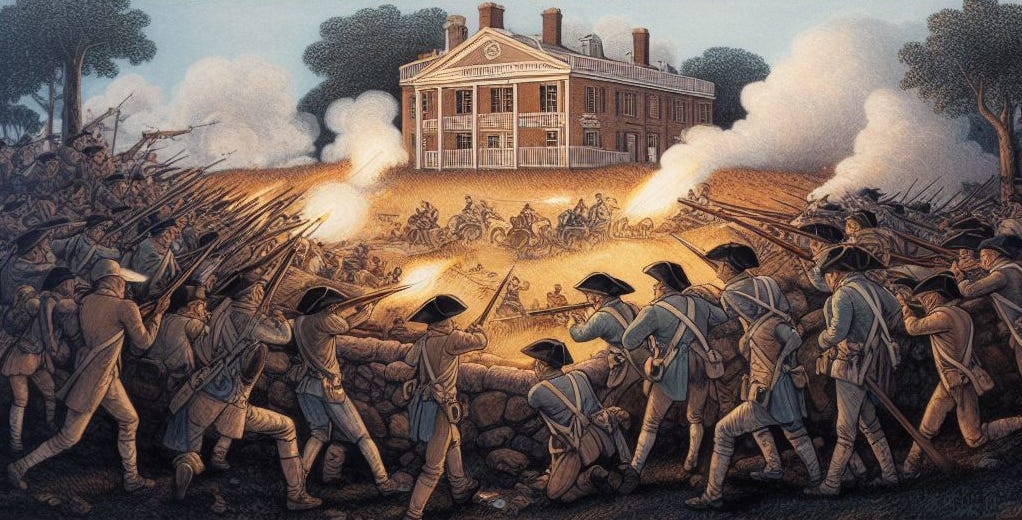

Second, there is an apparent close connection between Trump’s address and the start of violence. The Civil War legislators spoke months before violence started, but Trump’s speech began only minutes before violence started, and his supporters understood him to be directing them to commit violence. On a spectrum from Rep. John Price voting to “defend Southern honor” in January 1861 to P.G.T. Beauregard writing out the conditional attack order against Fort Sumter on April 11 1861, Trump’s speech on January 6 is closer to the Beauregard end of the spectrum.

Meanwhile, at 1:02 p.m., Pence publicly declined to adopt the Eastman Theory. At 1:05 p.m., he formally convened the electoral vote certification.

Outside, the attacking force was growing rapidly, thanks to Trump directing his supporters to march to the Capitol on exactly this path. Trump himself attempted to join his “movement” and personally lead them to the Capitol. He continued to express a desire to join his forces at the Capitol even after the insurrection was in full swing and he had become aware of the violence. Trump’s staff prevented him from going, over his vigorous protests. There is no evidence in the record suggesting that Trump’s reason for wanting to join the crowd was in order to quell their violence. (J587-592, 594) Put another way: the President’s staff had to violate orders in order to waylay the President’s affirmative attempt to take the lead of an ongoing insurrection that already considered him its leader.

Recall that the Greathouse defendants were also tried and convicted for merely attempting to join a rebellion. Was that different? Certainly. Was it different in legally relevant respects? I leave that, for now, to you and God.

Over the next few hours, the armed force loyal to Trump violently approached, forcibly entered, and illegally occupied the United States Capitol building. Their purpose was to prevent Congress from carrying out the constitutionally mandated certification of electoral votes, including by causing bodily harm to law enforcement and other public officials (especially Pence) who opposed them. (J637-688) Many were armed with weapons, pepper spray, and tasers. Some wore full body armor; others homemade shields. Many used flagpoles, signposts, or other weapons to attack police officers defending the Capitol. Some moved through the crowd and entered the Capitol in a “stacked” formation, a single-file configuration often used by special forces during urban combat or close-quarters operations. (G176) Early in the attack, Capitol Police located and seized a vehicle containing weapons, ammunition, and components for Molotov cocktails (G179), which may have kept January 6 from turning out much worse than it did.

The attack wasn’t a high-spirited oopsie. Nor was it just one or two bad apples. While they failed to achieve their aims, forces loyal to Trump did succeed in bringing about an unlawful delay in certification of the electoral votes unprecedented in the history of United States presidential elections.

Throughout the entire attack, Trump was kept continuously informed of developments. Starting at around 1:19 p.m., Trump sat in the President’s private dining room, glued to the news channels as information streamed in. (G171) During the next 79 minutes (until 3:38 p.m.), Trump received continuous entreaties to end the violence. They begged him to take a simple, easy, quick action: just tell his forces to leave the Capitol and peacefully disperse. These entreaties came from people in the room, like Pat Philbin, Eric Herschmann, Mark Meadows, Ivanka Trump, Jared Kushner, General Kellogg, Pat Cipollone; and from people outside the room, like Laura Ingraham, Mick Mulvaney, Rep. William Timmons (R-SC), Donald Trump Jr., Rep. Jeff Duncan (R-SC), Reince Preibus, Alyssa Farah Griffin, Rep. Chip Roy (R-TX), and Sean Hannity, among many others. Over and over again, Trump refused these entreaties. (J78-82)

At 1:49 p.m., the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department declared a riot at the Capitol. Trump was aware of this, but still refused to direct his forces to disperse.

At 2:13 p.m., Trump's forces penetrated all exterior defenses and entered the Capitol. Trump was aware of this, but still refused to direct his forces to disperse.

At 2:16 p.m., the Vice President was evacuated to a safer location. Trump was aware of this, but still refused to direct his forces to disperse.

This period of stubborn inaction is relevant to our insurrection inquiry for three reasons:

First, remember the 1867 case of Philip Thomas? He was disqualified from the Senate as an insurrectionist either because he allowed his son to join the Confederate army (and gave him $100 for the road) when he might have as easily withheld that permission (and assistance) and/or because he opposed the Buchanan Administration’s measures to suppress insurrection and defend national institutions and personnel. Through Thomas’s case, Congress established a precedent that, yes, if you have the power to stop or significantly impede the insurrection, but refuse to exercise your power, without ample justification, then you become a participant in that insurrection. If Senator-Elect Thomas was disqualified for simply arguing against the Buchanan Administration’s (weak-kneed) efforts to defend against an anticipated insurrection (which was still months away), how much moreso would the 1867 Senate have disqualified Donald Trump for successfully blocking far simpler and more efficacious defensive measures against an insurrection that was actively attacking the Capitol? They didn’t need Trump to clap his son in chains (or send him off starving); all they needed was for Trump to record a thirty-second video clip using the hot camera just down the hall!

Second, Trump’s obligations were much greater than Thomas’s. Thomas was just the Secretary of the Treasury (and a loving dad). Mr. Trump was the President. The President of the United States has a special duty, entrusted by the Constitution solely to the President, to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” The president has broad discretion to determine how best to do that, and courts are rightly very hesitant to question his judgment. Being president is very hard, and courts can’t be Monday morning quarterbacks. However, there are boundaries to this judicial deference to presidential decision-making, especially when the president’s “decision” appears to be to just allow the law to be trampled for no lawful reason. To my knowledge, Trump and his lawyers have never offered even an implausible reason for Trump’s silence during this 79-minute period. They have simply admitted that “in hindsight… President Trump’s response” may not have been “ideal.”

That’s not enough. If Trump affirmatively set aside his duty to take care that the laws be faithfully executed—even temporarily—in order to allow an insurrection to advance its goals, then Trump has certainly “perform[ed] any part, however minute, or however remote from the scene of action” in the insurrection, and is “actually leagued” with the attackers. If Trump’s silence was not intended to allow the insurrection to advance, then he ought to tell us: what was his intention?

I can even imagine plausible answers to this! I just haven’t heard any. On the current record, it appears that the best explanation of Trump’s actions during that period is that he was ignoring his own duties in order to give the attackers a few minutes to accomplish theirs.

Third, this period of silence should inform our judgment about Trump’s speech earlier. When we left the Ellipse with Trump a few paragraphs ago, it was still somewhat possible to maintain that Trump had really intended his speech to convey a peaceful message, that his forces had misinterpreted it, and that he therefore played no conscious role in the opening rounds of the insurrection that followed. But, if Trump really did intend his speech to be interpreted peacefully, why didn’t he say so once he saw the attack unfolding? He had an entire staff begging him to do just that. He had a phone. He made calls and tweets during this time. It would have taken thirty seconds to clarify that “peacefully” really did mean “peacefully.” Yet Trump absolutely refused to clarify. He consciously let his loyalists believe that his address had been a literal call to arms.

For me, that’s what seals the question of Trump’s intentions in his speech at the Ellipse. His refusal to clarify proves to me that Trump’s forces didn’t accidentally hear a directive to attack the Capitol; they heard that because Trump intended for them to hear a directive to attack the Capitol.

These are not the most damning moments for Trump, though.

At 2:24 p.m., while the Capitol was occupied, and although he was completely aware of the violence, Trump tweeted:

Mike Pence didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done to protect our Country and our Constitution, giving States a chance to certify a corrected set of facts, not the fraudulent or inaccurate ones which they were asked to previously certify. USA demands the truth!

The 2:24 p.m. tweet immediately—predictably, obviously—precipitated further violence, as crowds both inside and outside the Capitol surged forward. Within ten minutes, the armed force overran the Metropolitan Police C.D.U.'s line of defense. As they burst through, one insurrectionist told a police officer that he was there because the “boss” had told them to be there—that is, President Trump (J661).

Trump’s reaction to the violence, as reported by the J6 Committee, was chilling:

…the President, when told that the crowd was chanting “Hang Mike Pence,” responded that perhaps the Vice President deserved to be hanged. (J111)

It requires more imagination than I have to conceive of a way to interpret the 2:24 p.m. tweet—sent while Trump was staring directly at the news channels depicting the ongoing violence—as anything other than an intentional directive for his forces, already actively attacking the Capitol, to target Mike Pence.

Trump’s forces gleefully accepted his orders. During Pence’s subsequent evacuation, Trump’s forces came within forty feet of their principal target, and caused such fear of bodily harm that some of Pence's security detail, anticipating their imminent deaths, phoned family members to say good-bye. (J86)

Once more, with feeling, I remind you of Greathouse, the case Trump’s own lawyers cited in his defense:

[I]f war be actually levied—that is, if a body of men be actually assembled for the purpose of effecting by force a treasonable purpose—all those who perform any part, however minute, or however remote from the scene of action, and who are actually leagued in the general conspiracy, are to be considered as traitors.

I further remind you:

Among the cases mentioned by the writers of ‘an adhering to the enemy, giving him aid and comfort,’ are the following: …every species of treasonable correspondence with the enemy, although the intelligence may not have reached him.

Trump’s 2:24 p.m. correspondence over Twitter, whose intent seems unavoidably treasonable, did reach the insurrectionists. It received 24,000 Likes in under two minutes (J597) and demonstrably served as an accelerant for the violence.

However, I think Trump’s most damning moment of participation in the insurrection came over the next few minutes, when Trump continued calling Republican Congressmen to try to encourage them to baselessly contest the election results:

Minutes after drawing increased attention to his besieged Vice President, the President called newly elected Senator Tommy Tuberville of Alabama at 2:26 p.m. He misdialed, calling Senator Mike Lee of Utah instead, but one passed the phone to the other in short order.

President Trump wanted to talk objections to the electoral count. But Senator Tuberville—along with every other elected official trapped and surrounded in the building—had other things on his mind. (J598)

Tuberville hung up. Continuing his rounds, Trump spoke on the phone with House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy shortly thereafter:

“You have got to get on TV, you’ve got to get on Twitter, you’ve got to call these people off,” [McCarthy] said he told the President.

“[These] aren’t my people, you know, these are—these are Antifa,” President Trump insisted, against all evidence.

“They’re your people. They literally just came through my office windows, and my staff are running for cover. I mean, they’re running for their lives. You need to call them off,” Leader McCarthy told him.

What President Trump said next was… “Well, Kevin, I guess they’re just more upset about the election theft than you are[.]” The call then devolved into a swearing match. (J598)

Trump here is still trying to achieve his goal: preventing Congress from carrying out the legally-mandated certification of the electoral vote. That happens to be the exact same goal as that of the attacking forces who identify themselves as being loyal to him, the very forces he refuses to order to disperse.

Trump pursues this shared goal by calling elected officials who are under severe duress, facing grave bodily harm if they do not comply with the attackers’ wishes—which just so happen to be Trump’s wishes. When asked to call off the attackers, Trump not only refuses; he suggests the attacks are justified, because elected officials are refusing to comply with his and his supporters’ demands.

Imagine you own a small shop and two men come to your door. One of them, a friendly-looking sort, says he’d like you to donate some money to a local charity that he manages. You happen to know that there is no such charity; it’s just a front for the mafia. Then the other—a big, burly man who could clearly break you in two—growls.

The friendly guy explains that his companion is another local resident who feels very strongly about the importance of supporting local charity. The burly guy growls that he’ll hang you from a tree if you don’t pay up right now. The friendly guy says, “Hey, I don’t know the big guy, but he has a point, doesn’t he?”

When you don’t pay up, the burly guy slugs you in the face and starts to drag your bleeding form out the front door. The friendly guy calls after you, “Well, I guess my friend just cares more about poverty than you do.” As the burly guy starts stomping on your face, you know you need to either give the friendly guy some money, hope the police save you, or wait for death. Obviously, as soon as you give the friendly guy the money, the burly guy will stop stomping.

Even if the friendly guy is miraculously telling the truth and he’d never met the burly guy before entering your store (and, spoilers, he is very much lying about that), he and his burly pal cooperated, from the moment they entered, to extract money from you by the threat of violence. The fact that the friendly guy didn’t actually lay a hand on you doesn’t make him any less of an accessory to the assault.

These two guys are a team.

In this damning call to Leader McCarthy, we see Donald Trump and his insurrection were a team, too.

And, per Greathouse, “There are no accessories in treason.”

Too Little, Too Late: The Climb-Down

Between 2:24 p.m. and 2:38 p.m., Trump's daughter, Ivanka, attempted to persuade Trump to send a tweet to get the crowd to go home peacefully. Alas, President Trump "did not want to include any sort of mention of peace" in his next communication to his forces, leading to a colloquy "going over different phrases to find something he was comfortable with." (J599)

Finally, at 2:38 p.m., Ivanka prevailed upon Trump to send a tweet directing rioters to "stay peaceful." Trump did so, but refused to direct his forces to disperse or to allow Congress to resume the electoral vote certification. At 3:13 p.m., Trump again directed his forces to "remain peaceful. No violence!"

However, it was widely and reasonably understood at the time, by White House staff, by law enforcement, by Trump's forces engaged in the insurrection, and—to all appearances—by Trump himself, that, if Trump gave his forces anything less than a clear directive to disperse, his affirmative inaction would prolong the occupation of the Capitol and the concomitant violence. (J90-91) That’s exactly what happened.

At last, at 4:17 p.m., after National Guardsmen16 and other additional law enforcement had begun to arrive to combat Trump's forces, Trump broadcast a video message directing his now-outmatched forces to disperse. In response, many of Trump's forces, recognizing the video message as a directive from their commander, retired from the battlefield and dispersed. (J92)

If you doubted that Trump really had authority to command this force—at any time throughout January 6—the response to the video message confirms it. Had Trump instructed the crowd to disperse hours earlier, this all could have been avoided. Any U.S. President prior to Trump, including awful ones like Buchanan, would not have hesitated a moment to give that instruction to disperse.

At 6:01 p.m., Trump tweeted a justification for the actions he and his forces had taken throughout the day. He claimed they were protesting a stolen election. (J93) Trump still knew this was false, because the election had not been stolen. Regardless, this was the kind of pro-insurrection advocacy that got Congressmen-elect disqualified during Reconstruction. Meanwhile, the insurrection was still ongoing.

Hostilities between federal forces and Trump's forces concluded no sooner than 6:14 p.m., when federal forces successfully re-established a perimeter on the Capitol's west side. When all was said and done, only one person died in combat, making the J6 attack about half as deadly as the Battle of Bower Hill in the Whiskey Rebellion. Of course, as with the Whiskey Rebellion, the low body count didn’t make it any less of an insurrection.

At no time on January 6 did Trump acknowledge or condemn the violence that had already been committed by his forces, though he was aware of it. Trump has offered no reasonable, mitigating justification for his behavior that day.

However, even if you interpret his “stay peaceful” tweet as a sign of a changed heart, it was too late for Trump’s legal eligibility to serve as president. In his belligerent address to a crowd he knew planned (at least in part) to interpret his words as a call to arms, in his attempt to lead his forces personally, in his unconscionable refusal during the first 79 minutes to quickly and easily tell the crowd to go home, in his communication with the treasonous force targeting Mike Pence, and in his attempt to use the ongoing insurrection as leverage in his negotiation with Leader McCarthy (while aiming to accomplish the same goal as the insurrectionists), President Trump had already played a much-more-than-“minute” role in the January 6 attack on the Capitol and Constitution of the United States.

Trump’s Defense

To be fair, Trump’s lawyers have not fully set forward his defense. Their initial filing attempts to dismiss the claims of insurrection on their face, with only a couple dozen pages of argument. If the Minnesota trial reaches Phase II, where the insurrection question is squarely faced, they may get much deeper than this. They may find much better defenses.

They had better try, anyway.

Much of the Trump filing is spent defending various bad things Trump did that I didn’t even bother bringing up here. (I only had 15,000 words!)17

Much of the rest of the Trump filing argues that Trump’s “questioning” the fairness and accuracy of the election returns is not “insurrection.” Given the narrow definition of “insurrection or rebellion” we are using here, they are correct. It is nevertheless important to walk through Trump’s dishonesty about the election, because it set the table for his eventual participation in the insurrection of January 6. Even so, it must be said that Trump’s team is correct: lies are not, by themselves, an insurrection.

On the subject of lies, Trump’s filing states that, “Petitioners make a series of allegations that, in total, show that some people in the Trump Administration disagreed with the President about the effects of fraud or irregularities on the election or about the legal arguments he made in response.” He further disputes that the Petition “accurately characterizes what any particular person believed or told him.” For the reasons I laid out several sections ago, characterizing Trump’s lies about the election as a mere “disagreement” is like characterizing Bill Clinton’s perjury about having sex with Monica Lewinsky as an “intriguing lexical dialogue on the precise meaning of ‘is.’”

Moving on to the actual insurrection, the Trump filing points out that many of the facts alleged (like the Oath Keepers stockpiling weapons) were outside of Trump’s awareness or control. That is correct. Details like the weapons stockpiles are necessary to help establish that there was an organized, intentional insurrection (not merely a rowdy protest that got out of control), not to establish that Trump participated in that insurrection. Other details establish Trump’s participation in the insurrection, but we have to establish whether an insurrection exists first.

Team Trump contends that Trump demonstrated his desire for a peaceful protest on January 3, when he cursorily agreed, at the end of a national security briefing on a foreign threat, to allow D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser to request (J741) a few hundred unarmed National Guardsmen to perform traffic and crowd control duties (J726). Mayor Bowser ended up not making the request, which, I think it’s fair to say, turned out to be a big mistake. This is Trump’s best evidence on his side, I think, which is probably why he yells about it (alongside several falsehoods) in his letter to the J6 Committee. I just don’t think this evidence stands up against the other, better evidence on the other side of the question.

Trump himself, fabulist that he is, has exaggerated the January 3 conditional authorization into an affirmative order to deploy 10,000 armed troops. No such order, or anything remotely like it, was ever issued. At no time on or before January 6 did Trump direct the National Guard… or any law enforcement agency… to protect the Capitol from his supporters, even though he had the undoubted authority to do so. (J95) It seems that Trump did float the idea of having 10,000 National Guardsmen to protect his own rally (J534), and that military leaders were reluctant to become involved for fear that the President or others would politicize their involvement (J729-741).

Turning to his speech at the Ellipse, Team Trump insists that Trump’s speech came from a sincere belief that there was actual serious misconduct to prevent. I admit, if you can convince yourself that Trump actually believed that the election was stolen, it’s much easier (though still by no means easy) to read his speech as a mere firey call for change, rather than something worse. That’s why it’s so important to walk through what Trump actually knew at the time about the wild claims of fraud that he made in that speech.

The filing argues that, because Trump’s speech told his followers to march to the Capitol after the speech, but the attack actually began fourteen minutes before the end of Trump’s speech, the speech (and the thousands of reinforcements it provided) can’t possibly be connected to the attack. If I follow the argument correctly, Trump’s position is that it was simply an unlucky coincidence that the Proud Boys happened to attack the Capitol at the exact point where the crowd from the Ellipse would soon be arriving.

The filing asserts that “Nothing shows the President intended or supported violence.” This seems like an oddly strong claim to make, given all the people—including the attackers—who, hearing the speech, understood Trump to be both intending and supporting their violence. Trump does not explain how those people reached such a wrong conclusion, nor indeed mentions them at all. These people were Trump’s most loyal fans, willing to lay down their lives for him, and he makes out that they must have been delusional to hear what they heard from him. Under the bus with them!

To be sure, I think the Trump defense team may be right, in a narrow sense: if you ignore all of the surrounding context, impute good faith to the President’s fraud claims, forget about how the crowd interpreted the speech, and look at only the literal text of the speech, it’s at least fairly possible to read it as a sincere (if idiotically inflammatory) call for peaceful protest. The problem is that, when you do consider the context, recognize the evidence that Trump was not acting in good faith, and, especially, interpret the speech in light of what Trump did afterward, it looks much more like a deliberate effort by Trump to insurrect.

Summing up their position on the speech, Trump’s legal team asserts that it did not meet the Brandenburg standard for incitement to riot, and that “mere words cannot meet the Section Three standard unless they could, at minimum, qualify as incitement to violence under [Brandenburg].” I don’t think this is quite right, and, in their paper, Baude-Paulsen lay out ample reasons to doubt that the boundaries of the First Amendment are coterminous with the boundaries of Section Three.

However, I also don’t think it matters. For the reasons I laid out several sections ago, I think Trump’s speech does meet the Brandenburg standard: (1) the imminent use of violence or lawless action was the likely result of the speech, (2) the speech explicitly or implicitly encouraged the use of violence or lawless action, and (3) the speaker intended this result. The first element is easy because imminent violence was, in fact, the result of the speech; the second is made much easier by the existence of multiple eyewitnesses deeply loyal to Trump (and never renounced by him, even after the insurrection!) who understood the speech itself to be a call to violence; which leaves only the third element, Trump’s state of mind, which cannot be empirically known, but may be inferred from his prior and subsequent actions.

Speaking of subsequent actions—which, in my view, are the most important part of the whole case—Trump’s filing has nearly nothing so say about the 79 minutes between Trump being explicitly told about the attack at the Capitol and his first, half-hearted attempt to tell the attackers to “stay peaceful!”

Team Trump seems to believe that, because Trump eventually changed his mind and begrudgingly told his followers to “stay peaceful,” it’s all good! He didn’t even have to tell them to end their illegal occupation of Congress, or tell them to let Congress get on with obeying the Twelfth Amendment! As soon as Trump said “stay peaceful!”, apparently, his entire 79 minutes of dereliction was erased.

It doesn’t matter that Trump refused, for over an hour, to take care that the laws be executed (with no reason given, despite torrents of pleading). It doesn’t matter that he tried to get over to the Capitol to lead his “movement.” It doesn’t matter that he painted a target on the Vice President’s back. It doesn’t matter that he had used his insurrectionists as leverage to negotiate a better election certification. It doesn’t matter that he’d sent them to the Capitol in the first place! All the many ways Trump had contributed to the insurrection were retroactively sanctified, all because, at 2:38 p.m., Ivanka finally managed to beg him into grudgingly sending a “stay peaceful!” tweet that he hardly meant and that both he and those around him knew wouldn’t end the violence.

Do you buy that?

Well, Do You?

I have asked a lot of questions in this post. That’s because you are a jury of one here. If, having read this, you have come to agree with me that Trump “engaged in insurrection” against the Constitution—and, again, we used Trump’s own definition of “insurrection” for this—then you can understand not only why the Disqualification Clause applies to his actions, but why it’s a very good thing that it does. If you, like me, either voted for him both times, or at least justified voting for him, this might be a hard thing to come to terms with. Once you do, though, the solution is both obvious and unavoidable: we must follow the law, wherever it takes us. (Precisely what the law requires is what the rest of the Minnesota Disqualification Suit will determine.)

On the other hand, if you have made it through all this and you still don’t think that Trump’s activities rise to the level of “engaging in insurrection” or “levying war” or any of that, then that’s the end of the inquiry. There’s no point in exploring the other questions about interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment, because there’s no disqualification case without an insurrection. However, since even Trump’s own definition of “insurrection” seems to make him out as an insurrectionist, I would be very interesting in hearing how you reached the conclusion that he isn’t. This is between you and God, but, if you want to share, the comment box is open.

In a criminal trial, the prosecution must prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. If Trump were on trial for treason, a conviction would lead to his execution, or at least to a long prison sentence. Even the smallest reasonable doubt as to his state of mind would be enough to let him walk free. Even though he’s probably guilty, we would let him go if we weren’t certain of it. After all, it is better to let guilty men walk free than deprive even one innocent of his rights to life or liberty. At such a high standard of guilt, it might be quite difficult to reach that level of certainty about Trump’s state of mind. It might even be impossible.

However, this case does not propose executing Donald Trump, or even taking away his basic human liberties. This proceeding will determine only one thing: whether Trump can serve as President (again). That august privilege is denied to many millions of Americans (including all Americans under thirty-five). It is denied to people who engaged in insurrection, because it would be extremely dangerous for an insurrectionist (especially an unrepentant one) to serve again. Because it is the nation, not the candidate, that is in real danger here, the legal standard of evidence in this case is not proof beyond a reasonable doubt.